Originally posted December 2009

Over the last two years, the Government of Afghanistan (GoA) and international military forces have lost ground to the insurgency across the southern provinces of Kandahar, Ghazni, Zabul, and even Helmand, where recent military operations have been displacing civilians (and insurgents) without yet restoring government control or stability. Many areas that had once been relatively stable and under the (tenuous) control of the government have a regular and strengthening insurgent presence. Though 80% of the population across the south remains “pro nobody” — distrusting an ineffectual government and fearing a repressive Taliban — an increasing number of neutral communities are now forced to either recognize insurgent control in their areas as a matter of survival, or else flee. The factors contributing to this downward spiral are diverse and well-documented, if not fully understood.

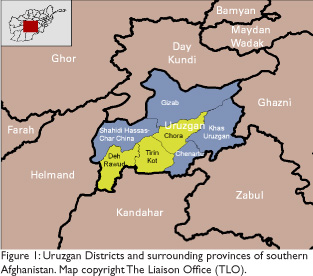

More interesting — and, from a policy perspective, more useful — is an analysis of Uruzgan: the single southern province to buck the regional trend of increasing volatility and grow more stable and come under greater (though still tenuous) government control over the last year and a half. Why has the situation improved here? And what role have international actors[1] played in this turnabout?

And it has been a turnabout. In the fall of 2007, only a year after NATO expansion brought Dutch and Australian forces to Uruzgan, the provincial capital was under regular attack, and an insurgency composed of former Taliban regime members, new recruits, and foreign fighters controlled virtually all of Deh Rawud (the birthplace of Taliban leader Mullah Omar) and Chora Districts. Today, Deh Rawud has the highest level of stability of any district in southern Afghanistan where the GoA is present;[2] the government now controls between 50 to 60% of Chora; and though key areas of Tirin Kot district are still under insurgent control, the provincial capital is no longer under siege and corridors of relative stability now link it with Deh Rawud, Chora, and even Nesh district of northern Kandahar, where residents confronted with an expanding insurgency in the southern part of their district now often travel to markets in Tirin Kot rather than Kandahar City. During the course of field work in Deh Rawud and interviews with individuals from Chora conducted in Tirin Kot City during the first week of August, I asked residents why and how the situation had improved in their areas. Not surprisingly, their answers provided no recipe for stability, though a number of overlapping themes did emerge.

The insurgency made a mistake and the communities mobilized themselves. In Deh Rawud the methods of foreign insurgents were so drastic and the bombardments and fighting in the district so heavy that the local population decided to support the government and remove insurgents as a way of getting rid of foreign insurgents and foreign bombs. A coalition of all tribes formed and put up a fighting force aided by international military forces.

In Chora insurgents burned stores of wheat and a newly constructed community building. After this incident, the largely Barakzai community located in the west of the district made a conscious and coordinated decision to turn towards the government and away from the insurgency. Though increased government and international security actors have positively impacted the security situation, many of those interviewed felt that in both districts this fundamental first step by the communities themselves was the sine qua non for bringing areas of the districts back under government control.

Traditional leaders have decision-making power. In Chora tribal elders and notables have been allowed to remain armed and have personal guards (often family members, usually no more than one or two). The fact that pro-government tribal elders have been able to keep a small security team (especially as many of them live in areas with no form of state police protection) has allowed them to remain in the district, which in turn has been a key factor in maintaining tribal and community unity, and garnering wider support for development projects and government initiatives.

After the government regained control of Deh Rawud district in late 2007, the Ministry of Interior directly appointed an Afghan National Army officer as District Governor (DG). Though the DG, an ethnic Tajik from outside Uruzgan, is still fundamentally seen by locals as an interim actor, his outsider status has been a blessing, as he has been less prone to entanglement in communal feuds, and has not been able to dominate local governance bodies in the way that native District Governors (many who are essentially local strongmen with a selective clientele) have done in the south since the fall of the Taliban.[3] As a result, local governance bodies in Deh Rawud have been given the breathing room that has allowed them to gain influence in their own right; and, in turn, communities now feel they have more say in development and governance issues facing the district.

Aid is reaching many communities who chose to turn against the insurgency. It is interesting that locals in Chora did not cite the presence of foreign military forces as a primary reason for increased security. They did, however, emphasize that the current Dutch engagement approach was not alienating the community or causing people to join the insurgency, compared to areas of Ghazni province where residents were able to provide examples in which aggressive house searches by US and Polish forces have shamed male family members into joining the insurgency to enact revenge and remove communal stigma. Further, aid/development which the Uruzgan Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) is bringing to Chora is now a key factor in gaining community support because it demonstrates to locals (in both government- and insurgent-held areas) the material benefits of turning towards the GoA. Using aid as a carrot in Afghanistan often has backfired and divided the communities it sought to help. In this case, the community’s decision to first turn away from the insurgency relied heavily upon the ability of tribal elders to make an effective case that it was in the group’s best interest to do so. Had aid then failed to reach these communities, these elders’ leadership would have directly been called into question and the area would have been ripe for the re-emergence of insurgent actors. While this is not necessarily evidence that aid/development directly contributes to stability, the fact that some residents in insurgent-controlled parts of the district have been voting with their feet and moving into government-controlled territory in order to access services is a positive sign. Likewise, many individuals in Shahidi Hassas, a district to the north of Deh Rawud still largely under the control of the insurgency, witness the development occurring in Deh Rawud and have organized a communal shura as a focal point for reaching out to development actors and planning potential development projects in their areas.[4]

There is still a long way to go in Uruzgan: The district of Gizab remains under tight insurgent control and fighting in the volatile district of Khas Uruzgan continues to generate internal displacement; communal divisions rooted in unequal access to resources and political representation remain; civilians are still being killed in coalition force airstrikes; and, most importantly from a sustainability perspective, GoA capacity remains low, with key provincial-level actors often working at cross purposes or in competition. Nonetheless, there is a shared feeling among many communities in the districts of Deh Rawud, Chora, and Tirin Kot that things are getting better — that, while the government is still weak, and corruption still exists, the GoA is gradually becoming more accountable, and corruption has at least fallen within range of “acceptable” levels.

As the Dutch Parliament debates if (and how) the Netherlands will withdraw from Uruzgan when its commitment to ISAF ends in the summer of 2010, it is crucial that the nation which steps in to fill the departing Dutch presence have the financial means and a strong aid and reconstruction network to maintain (and increase) the ongoing level of development. More basically, there must be a clear transfer of knowledge regarding best engagement practices and ground realities from the Netherlands civil-military mission to any incoming nation; or else this island of relative stability will be swamped by an increasingly volatile southern tide.

[1]. Mainly Dutch and Australian NATO forces, though US Special Forces are also present

[2]. Districts such as Gizab (Uruzgan) and Baghran (Helmand) arguably have been more stable over the last two plus years, but also completely controlled by insurgents. Hazara areas of Uruzgan and Ghazni are also considered to be stable, but the GoA has a limited presence here, and the areas have a de facto autonomous status. Another southern district with a GoA presence and a measure of stability is Spin Boldak (Kandahar).

[3]. These governance bodies include: a 29-person “development shura” composed of tribal elders and engineers who monitor the implementation of development projects supported by the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development; a 40-person tribal shura; and a 73-person malikan (village representative) shura that serves as a contact point for international actors.

[4]. A similar shura exists in Khas Uruzgan district. Both councils operate in areas with a high insurgent presence and are attempting to remain independent of both the government (so they are not targeted by insurgents) and the insurgency. This is a fine and dangerous line to walk, and in some cases it means maintaining direct lines of communication with the insurgency and/or incorporating moderate “local Taliban” into the council.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.