This essay series examines the roles that community-based organizations (CBOs) have played as active participants in the process of "governing" megacities whether in service delivery, risk mitigation, or the creation of livelihood and other opportunities. More ...

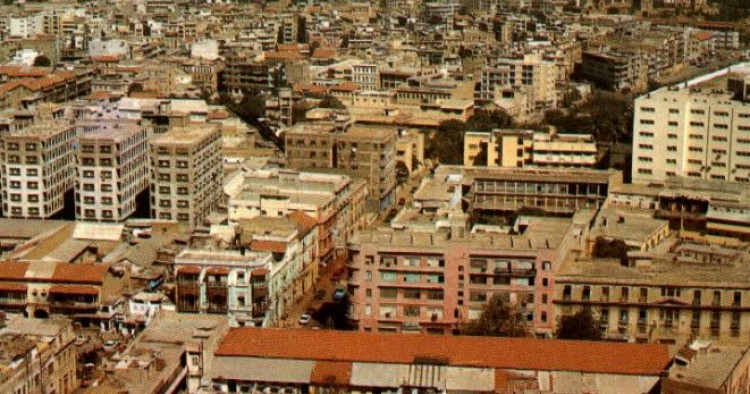

Policy and journalistic narratives of Karachi tend to focus on high levels of violence and crime,[1] and more recently, terrorism.[2] These accounts emphasize that access to basic amenities for a sizable part of the population in the city, home to at least 20 million people, is made possible through various “mafias.” These narratives evoke imagery of a city where the rule of law and state capacity are weak enough for non-state actors to step in and contribute to lawless pockets of violence and criminality.

This depiction is not without merit—crime ranges from petty crimes to gangs who are connected to the drug trade, traversing from Afghanistan through Pakistan to global markets. Violence is an intrinsic part of the city’s politics, although homicide rates are lower than in some Latin American countries.[3] Political parties not only have militant wings, but they also support and recruit hardened criminals, who together possess more advanced weapons than the local police. Almost all major political parties carry out extortion, target killings, and kidnappings.[4] The presence of terror groups such as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and al-Qa'ida operatives who moved to Karachi in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, and their subsequent involvement in extortion, kidnappings and bank robberies, adds to the perception of the city as a dangerous place.

This understanding of the city’s problems, however, is incomplete. It is premised on a traditional conceptualization of formal governance and the state, where state-society boundaries are distinct,[5] and state institutions are apolitical constructs, divorced from the wider political and social struggles at play.[6] Such an understanding fails to take into account connections[7] between state and non-state actors, which are integral to delivery of basic amenities for the poor, such as housing[8] and water. This narrative also fails to recognize how political patronage to criminals and their organizations, as well as tacit support from the state to some of these actors, lend legitimacy to their actions. Consequently, policy responses that focus only on the “criminal” aspect of dynamics at play in the city, without taking into account the facilitating role played by the state and the political system, address the symptoms of the problem and not its root cause. As a result, even if such policies gain ground in the short term, they end up contributing to more complex problems in the long run.

This essay argues that the conversation about Karachi needs to shift from viewing high levels of criminality as spawning ungoverned urban pockets to understanding how criminality, violence, and informality are shaping its political order. In this order, the state is not a passive player; it bestows and withdraws patronage to non-state actors in pursuing its larger interests. It purposely deregulates public services for some parts of the city and sections of the population. It also possesses the sovereign power to legitimize certain practices and actors, while delegitimizing others. The relationships between state and non-state actors are not driven solely by corruption. They are deeply political in nature, and have evolved over the years in the political, historical, institutional, and economic contexts of Karachi.

In turn, an informal and violent political order has taken shape. It is especially evident in the provision of water and housing to ordinary citizens. At present, the parallel water market[9] addresses at least 50 percent of the city’s demand for water.[10] Journalistic accounts attribute this informal provision of water to the 'water mafia.' Similarly, around 50 percent of the population lives in informal settlements.[11] Housing provision for residents who are poor, or barely making ends meet, is not the priority of the state administration. Instead, low-income housing is made possible through the informal real estate business that is locally described as the ‘land mafia.’[12]

This characterization of informal provision of water and housing through criminalized entities or networks limits our understanding. It presents an incomplete picture of the connections among political parties, government functionaries, and entrepreneurs, who are all motivated by different interests, but united in their efforts to be a part of the lucrative deregulation of housing provision and water delivery. These efforts are emblematic of political contestation as housing and water provision translate into political support for political actors. They also illustrate the myriad ways that the state is connected to these dynamics. Practices include government functionaries selling agricultural land on the fringes of the city for personal profit.[13] Political parties are actively involved in this racket, be it through land grabbing, hiring their affiliates in government institutions, or through development projects, if they are part of the government.[14] An example is the phenomenon of 'china-cutting,' in which major political parties, such as the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM),[15] government functionaries, and individuals benefiting from the practice subdivide large amenity plots and public spaces into small plots and sell them in the open market.[16]

Land grabbing and informal housing, however, are not just about economic gains. They are the tools employed by political parties to establish constituencies of support by enabling access to housing for ordinary citizens.[17] Most of the time, these new constituencies are comprised of members of their own ethnic background. For example, the PPP cater to the needs of Baluchis and Sindhis, the MQM to Mohajirs, and the Awami National Party (ANP) to the Pashtun population of the city.

In informal water provision, powerful players, including political parties, police officials, and bureaucrats in the institution responsible for water and sanitation, KWSB (Karachi Water and Sewerage Board), are involved.[18] Political players regard appointments to the KWSB as extremely valuable, given its key role in supplying water to the city. These appointments can be useful in maintaining influence in the informal water provision market as information about new or upcoming water distribution development projects is a highly sought-after commodity before it becomes public. As a result, players can adjust their strategies accordingly to take advantage of parts of the city becoming developed, which can raise their market value.[19]

Yet, while political actors make economic gains through their involvement in these practices, they are driven to be part of this informal network to ensure their access to economic and political benefits. In a city where ethnicity is a decisive marker in urban politics, and violence has become an accepted norm among players for resolving disputes,[20] getting access to water and housing are not just urban problems. They illustrate the wider struggles at play among political contenders for the city’s resources.

Similarly, some practices, despite being criminal in nature, are also emblematic of political contestation. A striking example of this phenomenon is extortion, which has been a widespread practice in Karachi since the 1990s. Introduced by the MQM, the political party representing the largest section of the population, the Mohajirs,[21] it began to be carried out by other political players between 2007 and 2013. The crime groups of Lyari,[22] connected with international drug smuggling networks and supported by the PPP,[23] also delved into the practice of extortion. Soon enough, other political players, including the ANP representing Pashtuns, and religious parties with sectarian outlooks followed suit. Payment of extortion guaranteed that the payee’s life and assets were protected from harm. That political players other than the MQM were now involved in extortion was a watershed development, challenging the erstwhile hegemony of the MQM.[24]

The practice of extortion by political parties was followed by a new type of actor in the urban terrain of Karachi, the aforementioned TTP—a conglomeration of fighters from the Taliban and Al-Qa'ida. Initially using the city as a hideout, where they engaged in organized crime to raise revenue for jihadi activities, these militants joined hands in 2008 with the goal of establishing a Shariah state in Pakistan.[25] The TTP soon introduced itself as a political player by violently displacing the leadership of the ANP, the political party representing the Pashtun population of Karachi. They also began to engage in land grabbing and extortion, as well as dispensing Shariah-style justice in some pockets of the city.[26] These developments signaled the emergence of a player, which unlike other armed actors in Karachi, favored divine law over the country’s constitution. They also illustrated the rapid evolution of a terror group into a political protagonist.

So what policy responses can be proposed in a city like Karachi? In understanding how the urban terrain of Karachi includes a variety of political players, it is easy to focus solely on the rise in violence, crime, deregulated service provision, and a terror group. This essay argues against this conceptualization. Instead, it makes the case that inter-linkages among different players and practices at work in Karachi are not just criminal and violent, they are political as well—focused on acquiring control of the city’s political and economic resources. The state plays an important role in this order, thereby challenging the argument of state failure in places like Karachi.

For global policymakers, it is important to shift the focus of the debate on Karachi and other similar locations from breakdown of governance to developing a ground-up understanding of the violent and informal orders that are at play. This calls for revisiting the perception of these places as “feral” in nature[27] and as future battlegrounds of conflict, and regarding them instead as places where complex phenomena such as climate change, global pandemics, crime-terror-corruption entanglements,[28] migration flows, and so forth, interact with existing orders.

The evolution of the TTP from a terror group to a possible player in Karachi’s politics represents an important case study. Developing an understanding of how seeming disorder in cities like Karachi persists and functions can help illuminate whether they are one step away from conflict, or are places where informal and violent political orders are the new equilibrium.

[1] Asad Hashim, “Interactive: Karachi’s killing fields,” Aljazeera, September 6, 2012,

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2012/08/201282210292095192….

[2] Samira Shackle, “Karachi vice: inside the city torn apart by killings, extortion and terrorism,” Guardian, October 21, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/21/karachi-vice-inside-city-r….

[3] Juan Forero, “Medellin’s efforts against crime prove fleeting” Washington Post, June 13, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/medellins-efforts-against-crime-pro….

[4] Supreme Court of Pakistan, “Watan Party v. Federation of Pakistan,” All Pakistan Legal

Decisions (Lahore: Pakistan Legal Decisions Publishers, 2011) , pp. 997–1134.

[5] Joel S. Migdal, Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World (Princeton: NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

[6] Shahar Hameiri, “Capacity and Its Fallacies: International State Building as State

Transformation,” Millenium: Journal of International Studies, 38:1 (2009), pp. 55–81.

[7] Javier Auyero, “Clandestine Connections: The Political and Relational Makings of Collective Violence,” in Enrique Desmond Arias and Daniel. M. Goldstein, Eds., Violent Democracies in Latin America (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 108–132.

[8] Nezar AlSayyad and Ananya Roy, “Urban Informality: Crossing Borders,” in edited by Nezar AlSayyad and Ananya Roy, Eds., Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia (Lanham, MD and Oxford: Lexington Books, 2004), pp. 1–7.

[9] Orangi Pilot Project-Research and Training Institute, Orangi Pilot Project: Institutions and Programs (Karachi, 2013).

[10] Parveen Rahman, Water Supply in Karachi: Situation/Issues, Priority Issues and Solutions (Karachi, 2008), p.15.

[11] “Majority of city’s population lives in slums, seminar told,” The Daily News, April 18, 2011, http://www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=42185&Cat=4.

[12] Arif Hasan, Noman Ahmed, Mansoor Raza, Asiya Sadiq, Saeeduddin Ahmed, and Moizza B. Sarwar, Land Ownership, Control and Contestation in Karachi and Implications for Low-Income Housing (London, 2013).

[13] Ibid.

[14]Based on interviews with author carried out in September 2013 in Karachi, Pakistan.

[15] Ali Arqam, “This land is my land,” Newsline, May 21, 2015,

http://www.newslinemagazine.com/2015/05/cover-story-this-land-is-my-lan….

[16] “What exactly is ‘china-cutting’?”ARY News, June 16, 2015, http://arynews.tv/en/what-exactly-is-china-cutting/;

And Imtiaz Ali, “MQM leader’s brother, others booked for China-cutting business, money laundering,” The Daily Dawn, September 5, 2015, http://www.dawn.com/news/1204952.

[17] Based on interviews with author carried out in September 2013 in Karachi, Pakistan.

[18] “KWSB Chief quits over ‘political pressure,’” The Daily News, September 7, 2012,

http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-4-130442-KWSB-chief-quits-over-po….

[19] Based on interviews with author in September 2013 in Karachi, Pakistan.

[20] For insights about how violence became a norm in Karachi’s politics, see Laurent Gayer, Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[21] Mohajirs, literally meaning migrants in the Urdu language, represent people who migrated from India to Pakistan in 1947 at the time of both countries’ independence. See Supreme Court of Pakistan., “Watan Party v. Federation of Pakistan,” All Pakistan Legal Decisions (Lahore: Pakistan Legal Decisions Publishers, 2011), pp. 997–1134.

[22] Lyari is the oldest neighborhood of the city.

[23] Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), although national in outlook, is representative of Sindhis and Balochis in Karachi’s politics.

[24] Laurent Gayer, Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 255.

[25] Hasan Abbas, “A Profile of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan,” Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point, January 15, 2008.

[26] Zia ur Rehman, “Taliban Collect Funds through Extortion, forced Zakat, officials say,” Central Asia Online, August 1, 2012, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/features/pakistan/main….

[27] Richard J. Norton, “Feral Cities,” Naval War College Review, 56:4 (2003), pp. 97–106.

[28] Louise I. Shelley, Dirty Entanglements: Corruption, Crime, and Terrorism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.