Originally posted December 2009

In September 2003, armed police and bulldozers violently ejected around 250 people from land in central Kabul and demolished their homes to make way for the lavish mansions of the freshly empowered elite.[1] Sherpur, as the area is known, lies in the shadow of the diplomatic enclave and as such is some of the most valuable land in the capital.

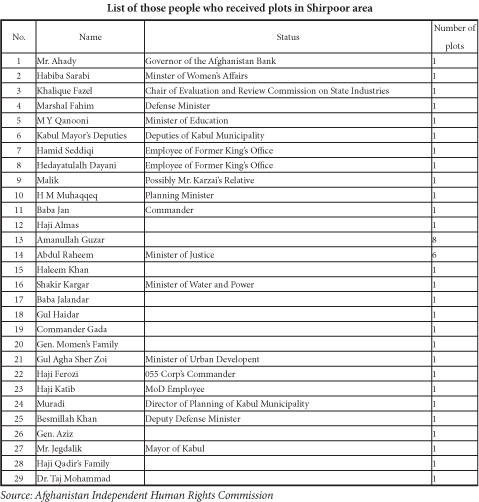

Amidst a public outcry, the fledgling Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) spoke out strongly against the land-grab and released a list of 29 senior officials and powerful individuals,[2] including six cabinet ministers, the mayor of Kabul, and the governor of the central bank who had received plots. By other estimates — with ownership often obscured by the plot being given to powerful people’s relatives — only four of the 32 cabinet ministers in the interim administration did not accept land.[3]

What the evictions in Sherpur made clear — literally concrete, as the new mansions sprang up — was that this was to be business as usual. New regimes over the ages had grabbed and redistributed land as patronage to their supporters, and nothing was going to change with the 2001 intervention. The international community would stand back and watch, as the men they had rearmed and re-empowered to drive out the Taliban, and continued to support militarily and financially, divided up the spoils of war right next-door to their embassies. This was the “light footprint” in action.

Sherpur was an area redolent in history, having been the site of the ill-fated British cantonment during the second Anglo-Afghan War in 1879. It remained largely military land, now in the hands of the Afghan Ministry of Defense, many of those driven off had been squatting for decades amidst the various conflicts.[4] The Defense Minister, Marshall Muhammad Fahim, was demonstrating his power and proffering patronage to his peers at a time when the Northern Alliance was at the very zenith of its post-2001 political and military power. Kabul’s Deputy Mayor, Habibullah Asghary — who received a plot himself — explained that: “The Defense Ministry distributed the land to its commanders and high-ranking officials who defended our country and freedom.”[5]

Technocrats too, even those who had spent years abroad in well-paid jobs, claimed their piece of the action. Then-Central Bank governor (later Finance Minister) Anwar Ahady, freshly returned from a teaching position at Providence College in Rhode Island told the media that he was entitled to the land and denounced anyone who dared criticize the process, as participating in “political terrorism.”[6]

Then-Education Minister Younus Qanooni (now Wolesi Jirga speaker) agreed, telling the same press conference that while state land was being transferred to individuals it was being done legally: “There is a difference between those who are given land by the current rulers under current laws and those who take land by force.”[7] One of the very few Afghan officials to publicly condemn the move was then-Finance Minister Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, who correctly foresaw that “when land is taken like it was in Kabul a few days ago, this creates a crisis of governance.”[8]

The AIHRC led the way in exposing those involved in the scandal with its head Sima Samar and Commissioner Nader Nadery bravely and strongly speaking out. The UN Special Rapporteur on Housing and Land Rights, Miloon Kothari, was also coincidentally in Kabul and expressed deep disquiet — calling for dismissals. “Fahim, the minister of defense, is directly involved in this kind of occupation and dispossession. And ministers that are directly involved have to be removed,” he told the press.[9]

For this, Kothari was reproved by the UN’s Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG), Lakhdar Brahimi, who clarified after his letter was made public that while they agreed in substance, individuals should not have been named publicly.[10] The international diplomatic missions also preferred a “neutral” silence even as they provided the military and financial backing to these same men.

Meanwhile, at the palace, President Hamid Karzai’s staff insisted that it had all been done without his knowledge. However, the non-response — setting the stage for many scandals to come — was to create an “independent” investigative commission.[11] It completed a report in October 2003 which has never been publicly released.[12] The only tangible action was the removal of the Kabul police commander Abdul Bashir Salangi, who had led the forceful eviction, which resulted in reports of injuries. Although, in a maneuver foreshadowing the response to many a future outcry — he was immediately given another job in Wardak.

What emerged from the rubble of the simple mudbrick homes were tasteless mansions of sparkly jewel-bright clashing colors, mirrored glass, three-storey colonnades, and faux Greek pediments. They were modeled on the gaudy constructions that had sprung up in Peshawar during the decades of war — simply predicated on massive unaccountable cash flows — referred to by expats as “narcotecture.” Bulging damp patches along the external walls marked the poor quality of the construction with a lack of insulation meaning they are singularly unsuited to Kabul’s harsh weather.[13] This was, after all, about ostentatious display, rather than creature comforts.

Six years on, most of the new owners have completed their building work and foreign organizations — including embassies, media groups, UN agencies, and even rule of law projects — are moving in and rewarding their landlords with rents often well over $10,000 a month. Fahim, having been dumped by President Karzai in 2004, looks set to return as Deputy President. His ally, Bashir Salangi — vetted out of the police force altogether in 2006 — has been appointed Governor of Parwan province.

The Sherpur evictions were a seminal event in puncturing the enormous hope that had surrounded the 2001 intervention. The resulting mansions serve as monuments to the powerlessness of ordinary Afghans and a daily reminder to Kabulis of the impunity of the new administration and international inaction in the face of it.

[1]. For accounts of events see “Adequate Housing as a Component of the Right to an Adequate Standard of Living,” Report by the Special Rapporteur, Miloon Kothari Addendum, Mission to Afghanistan (August 31-September 13, 2003), E/CN.4/2004/48/Add.2, March 4, 2004 and the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, Annual Report: 2003-2004, p. 28.

[2]. Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Land Grab Scandal in Kabul Rocks the Government,” Radio Free Europe, September 16, 2003; Pamela Constable, “Land Grab in Kabul Embarrasses Government,” The Washington Post, September 16, 2003.

[3]. “Housing Plan for Top Aides in Afghanistan Draws Rebuke,” The New York Times, September 23, 2003; Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Land Grab Scandal in Kabul Rocks the Government,” Radio Free Europe, September 16, 2003 and Pamela Constable, “Land Grab in Kabul Embarrasses Government,” The Washington Post, September 16, 2003.

[4]. A Defense Ministry spokesman insisted that Fahim was simply acting in accordance with master plans for the city: “these houses are planned according to the master plan for Kabul. Marshall Fahim doesn’t have any intention to interfere in the plans of the municipal authorities in Kabul,” in “Karzai ‘to stop officials’ land grab,’” BBC, September 12, 2003.

[5]. Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Land Grab Scandal in Kabul Rocks the Government,” Radio Free Europe, September 16, 2003.

[6]. Pamela Constable, “Land Grab in Kabul Embarrasses Government,” The Washington Post, September 16, 2003.

[7]. Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Land Grab Scandal in Kabul Rocks the Government,” Radio Free Europe, September 16, 2003.

[8]. “Karzai ‘To Stop Officials’ Land Grab,’” BBC.

[9]. Ron Synovitz, “Afghanistan: Land Grab Scandal in Kabul Rocks the Government,” Radio Free Europe, September 16, 2003.

[10]. His letter of reproof was publicly released by Qanooni at the press conference to back his claim. Brahimi then insisted that there was “absolutely no disagreement” with Kothari on substance but criticized the public naming of officials. Pamela Constable, “Land Grab in Kabul Embarrasses Government,” The Washington Post, September 16, 2003. A spokesman explained: “For the united Nations to make a statement of that important we need to have a lot of substance to justify it,” in “Press Briefing by Manoel de Almeida e Silva, Spokesman for the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Afghanistan,” September 18, 2003, available UN News Centre.

[11]. Presidential Order No. 3861.

[12]. “World Chronicle,” United Nations, Program No. 938, recorded April 27, 2004. Guest: Miloon Kothari.

[13]. Anne Feenstra, “Kitschy Kabul Wedding Cake,” Himal, October 2008.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.