As the dust settles on the wave of Arab normalization toward the Syrian regime, questions persist regarding its impact on the daily lives of Syrians and the process of rebuilding their country. There are several reasons for uncertainty over the availability of reconstruction funds in the near future. The Arab League’s roadmap does not include any commitments for financial assistance or reconstruction funds, particularly considering the Gulf states’ recent shift toward conditional aid policies, not to mention the continued U.S. and EU reluctance to normalize relations with Bashar al-Assad. Despite the considerable humanitarian and financial assistance Damascus received after the February 2023 earthquake and the temporary lifting of sanctions, the Syrian economy has not recovered, with the Syrian lira reaching 9,500 against the dollar by July 2023. This suggests there is also a need to consider the structural and internal factors of the country’s economic crisis.

There is no doubt that Syria suffers from a deep financial crisis due to years of destructive war and economic isolation. However, domestic factors such as public expenditure diversion, corruption, and aid politicization should be considered equally as well. Examining the Syrian regime’s strategies for managing and allocating domestic reconstruction funds provides useful insights on what reconstruction under Assad would look like if any external funds were to become available, given the current operational, legal, security, political, and bureaucratic obstacles.

One of the main structural obstacles to Syria’s recovery is the policy on domestic reconstruction spending that the regime has applied since the early years of the Syrian conflict. This policy has two characteristics: diverting local resources dedicated for reconstruction purposes to rehabilitate facilities in areas and sectors that benefit the regime and its inner circle, and placing the burden of rehabilitating properties onto Syrians themselves. To finance this policy, the regime has exploited four key resources, including imposing multiple reconstruction taxes, diverting U.N. and international NGO (INGO) early recovery and rehabilitation projects, capitalizing on local-led crowdfunding campaigns, and forcing Syrians to bear the cost of repairing their own damaged properties.

As will be shown in this article, it is estimated that the Syrian regime may have mobilized more than $2.7 billion for reconstruction purposes from local resources since 2013. While this amount remains a small fraction of the total needed to fully rebuild Syria, it would have been sufficient to repair a large number of properties and public facilities. To put this figure into perspective, an assessment carried out by UN-Habitat in 2022 estimated that the total cost of residential sector damage in Homs, which encompasses 200,000 damaged housing units, amounts to approximately $1.3 billion. Another report by the World Bank estimated that the total cost of physical damage in the 14 largest war-torn cities in Syria ranges between $5.8 billion and $7.8 billion. There is little evidence that the Syrian regime has effectively utilized domestic reconstruction funds to repair damaged neighborhoods and towns or reduce overall destruction. Instead, it has manipulated, diverted, and siphoned off funds and aid intended for reconstruction and early recovery.

Seizing reconstruction money with no reconstruction

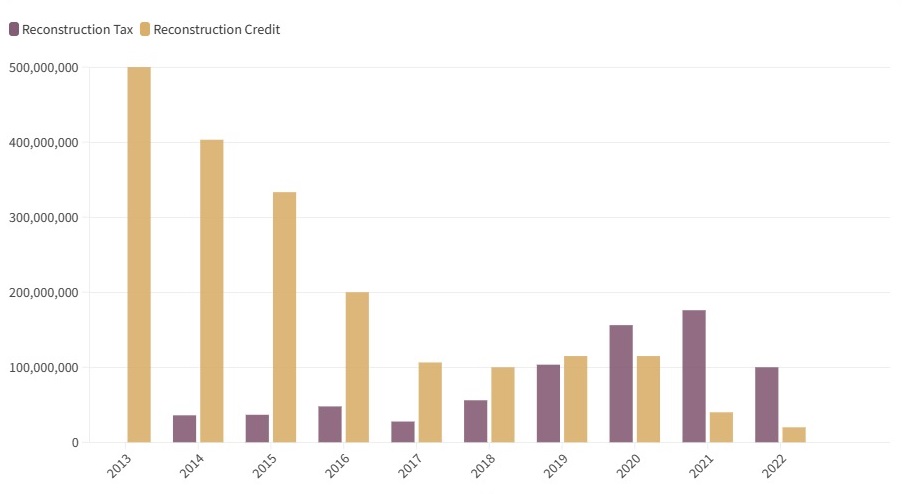

Just two years after the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011, the regime implemented the first tax for reconstruction, known as the National Contribution. A 5% additional tax on all other taxes and fees (excluding income tax), it was subsequently increased to 10% in 2017. Official statistics indicate that between 2014 and 2022, the total revenue generated from reconstruction taxes amounted to approximately 645 billion SYP (or around $739.6 million). Additionally, an annual budget allocation of 50 billion SYP, known as the reconstruction credit, is also dedicated to reconstruction, resulting in a further 480 billion SYP (approximately $1.93 billion) allocated since 2013. Both the reconstruction tax and reconstruction credit are intended to finance projects approved by the Reconstruction Committee, a body established in 2012 by the prime minister to oversee governmental rehabilitation plans and provide compensation to citizens.

Figure 1: Revenues from the Reconstruction Tax and Reconstruction Credit, 2013-22 (in USD)

Source: The Syria Report

However, an investigation conducted by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), Siraj, and Finance Uncovered in 2021 revealed that out of the 380 billion SYP originally allocated by the government by that time for reconstruction, the committee had pledged only 263 billion SYP. This lack of transparency is by no means surprising, but the investigation points out a particular bias in the distribution of funds: The majority went toward the rehabilitation of government and military buildings, while less than 10% was used to rebuild citizens' homes.

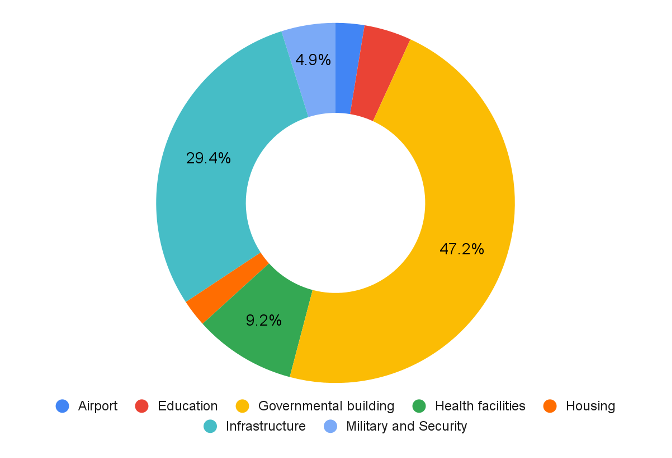

Further evidence confirming this claim can be found in the committee's list of projects in 2018. The data clearly show a substantial portion of the funds — over 52%, amounting to 34.8 billion SYP — being dedicated to rehabilitating governmental buildings and security headquarters, while less than 2.5% was designated for the housing sector. In fact, the most ambitious project announced by the Ministry of Local Administration, an effort to repair 3,000 houses in Eastern Ghouta unveiled in in May 2019, was not funded by the government at all, but by a coalition of local and INGOs (including Syrian Arab Red Crescent and Syria Trust) — and it seemingly has not materialized.

Figure 2: Sectoral distribution of projects proposed by the Reconstruction Committee, 2018

Source: The Syria Report

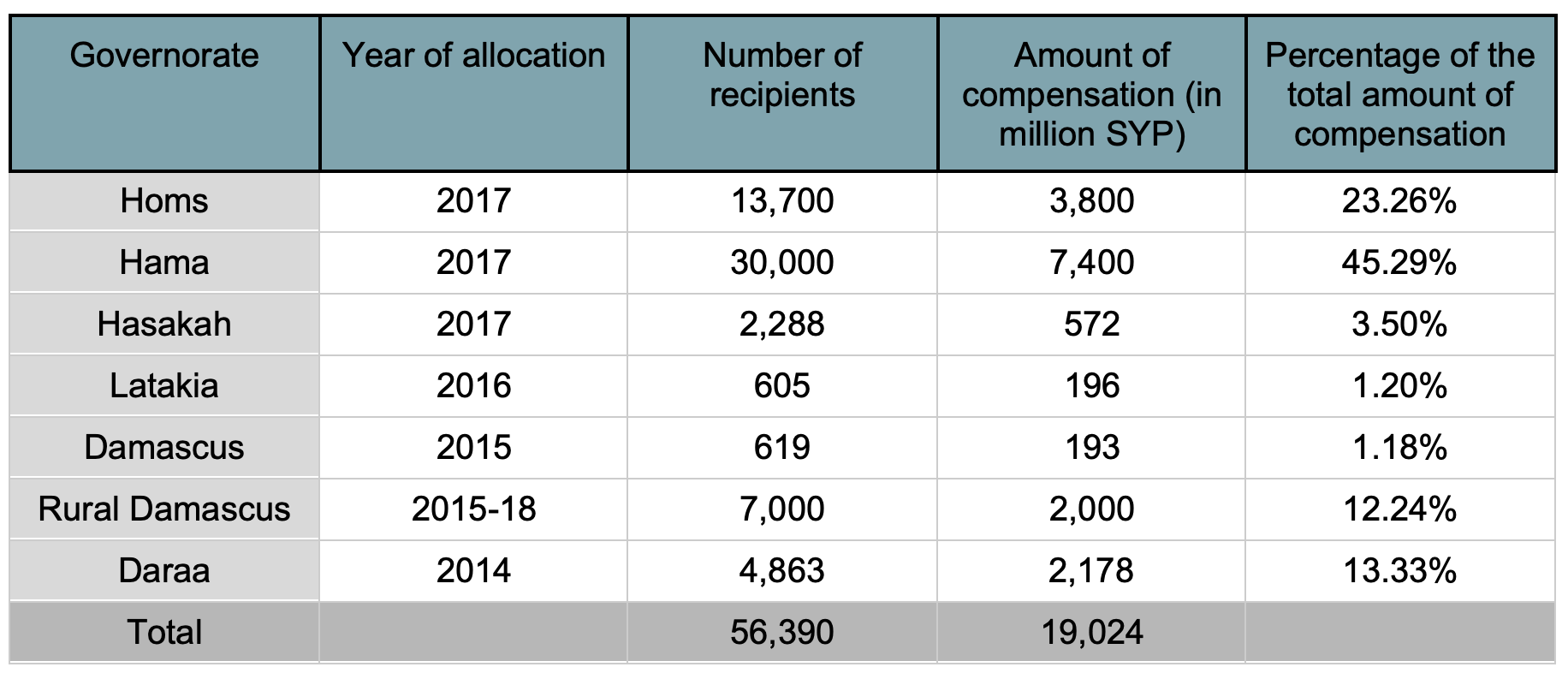

While some may argue that the government’s policy was to provide compensation for people rather than directly rehabilitating their properties, evidence obtained from multiple sources reveals that the practices in this regard were no less dubious. Data spanning from 2015 to 2018 demonstrate that out of over 313 billion SYP allocated for reconstruction, only 19 billion SYP was granted to 56,390 citizens as compensation for property damage, despite a far larger number of applications. To give an example, by the end of 2018, fewer than 9% of applications in rural Damascus were approved. The compensation usually covers between 30% and 40% of the reported cost of damage, up to 10 million SYP. However, applicants received on average around 300,000 SYP, which amounted to $600 as of 2018.

In the majority of cases where compensation was granted, it was in relatively less affected districts in Homs and Hama, leaving less funding for highly damaged areas, thus casting doubt on the selection process and raising concerns about nepotism, corruption, and politicization. Moreover, applicants are required to provide proof of property ownership and clearance letters from electricity and water companies, which creates barriers for those in informal areas without official ownership documentation and in former opposition areas where services were disrupted for years.

Table 1: Compensation for citizens affected by the conflict

Source: Ministry of Local Administration and Environment & SANA (cross-referencing with open sources)

The regime’s focus on generating more reconstruction funding included other, smaller sources as well. For instance, a Reconstruction Tax has been imposed on remittances since May 2021, a flat-rate deduction of 2,650 SYP on any incoming transfer from abroad, taking money away from thousands of Syrian households that rely on such transfers as their sole means of financial support. Given estimated daily transfers of $5 million to $7 million, it is possible that the regime has collected between 59 billion and 114 billion SYP (equivalent to $28 million to $54 million) from this tax to date. Since this tax has not yet been formalized, its contribution to reconstruction efforts remains uncertain. On a smaller scale, a special stamp for reconstruction (priced at 50 SYP) has been required for governmental transactions since 2013, with some officials arbitrarily demanding higher prices of up to 5,000 SYP for the same stamp.

Syrians paying again for reconstruction

The second aspect of the regime’s policy includes shirking its obligation to repair and rehabilitate damaged properties and infrastructure, instead shifting that responsibility onto local initiatives, INGOs, and ordinary people. As a result, Syrians are left to fill these gaps on their own. Indeed, despite extensive aid provided by the U.N. and INGOs, repairing houses and public facilities has not been a priority due to its high cost and scope that goes beyond humanitarian purposes. For example, in 2021, the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) managed to repair only 105 houses in Deir ez-Zor City, while the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) repaired 170 houses in Daraa City between 2020 and 2022. The two cities contain at least 6,400 and 1,500 damaged houses, respectively.

Housing rehabilitation provided by humanitarian organizations is not only limited but also highly politicized due to regime influence over the selection of locations and beneficiaries. Informal and heavily damaged areas, where most of the damage has actually taken place, are usually excluded from these projects. Moreover, the priority is often given to the families of “martyrs and wounded people,” clearly favoring pro-regime communities.

In response, local grassroots initiatives have emerged in various parts of the country, such as Daraa, Homs, and Rural Damascus, often led by religious, tribal, and civil society actors. One notable initiative was spearheaded by tribal leaders in several communities in Daraa Governorate. The campaign aimed to collect donations from local residents and businesses to finance services and repairs to infrastructure like wells and schools, raising up to 31 billion SYP ($4.5 million). In another case, more than 3,000 volunteers in the Yarmouk Camp in Damascus took the initiative to remove rubble from the camp’s main streets.

The regime encourages such initiatives when it can reap political or economic benefits from them. For instance, aiming to address the limited return to Maarat al-Numan and the lack of service restoration after three years of regime control, Damascus urged tribal notables and local militia groups to contribute to rehabilitating the local council building and main roads, as well as to provide financial support to encourage displaced families to return (up to 1 million SYP per family or around $120). Furthermore, reports from Daraa suggested that the regime not only attempted to take credit for this by ensuring government officials were present during the campaign, but also requested a share of the collected funds and asserted the government’s ownership over implemented projects in return for permitting such activities to take place.

Local participation in rehabilitation efforts is not always voluntary. In January 2023, the Damascus Governorate Council ordered the residents of the Yarmouk Camp to remove their collapsed buildings within a month and threatened that the council would charge them for debris removal if they failed to comply. Similar practices have been observed in other heavily damaged areas like Qabun, where people were given six months to rehabilitate their properties.

Even if people find the financial means to rehabilitate their damaged properties, they still have to deal with a multitude of bureaucratic and security obstacles, including proving ownership, obtaining construction permits, passing the technical safety inspection (which might cost up to 1 million SYP or around $120), and obtaining security clearances, a process that is often riddled with corruption and demands for bribes.

The risks and obstacles are far from over even after a property has been rehabilitated. One major risk is the threat of further looting. Repaired houses could be looted again by militia groups and local gangs affiliated with regime military and security units. For example, in the village of Oweinat in Latakia, where residents managed to rehabilitate 38 houses upon their return, 27 of those houses were looted for a second time (including windows, doors, electrical appliances, and building contents such as steel and copper electricity wires), rendering them uninhabitable once again.

From a legal perspective, those repairing their houses in informal settlements might also face the threat of demolition by the municipality. To make matters even worse, returnees are often compelled to sign documents relinquishing their rights to the rehabilitated properties without any compensation if the area is ever included in an urban development zone.

All of these factors result in an uneven distribution of rehabilitation across the country, ultimately favoring the neighborhoods where a majority of locals are affiliated with the regime or where pro-regime security and militia groups are influential. For instance, Crisis Group’s assessment in Aleppo found that by 2021, most reconstruction works were concentrated in regime-allied, militia-influenced neighborhoods such as al-Sukkari and al-Qatirji, while the number of projects undertaken in neighborhoods controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) such as Sheikh Maqsoud was minimal.

Overcoming Syria’s rehabilitation challenges

The bleak reality of Syria’s reconstruction has two sides: The regime not only deprives Syrians of assistance to rebuild their life by misusing the funds that should have been spent on reconstruction, but it also subjects them to flawed security, legal, and operational frameworks when forcing them to do so on their own. The current reconstruction policy is deeply flawed for multiple reasons.

First, the policy is highly selective on multiple levels. Geographically, it prioritizes areas that offer greater economic and political benefits, while neglecting highly damaged, informal, and impoverished towns and neighborhoods. Politically, the regime marginalizes former opposition areas with the aim of reshaping their social and economic fabric. Economically, it prioritizes neoliberal urban development projects at the expense of affordable housing, agriculture, and industrial sectors.

Secondly, it shifts the responsibility of service provision from the state to the people, placing a double burden on Syrians. On the one hand, the regime taxes them for reconstruction but diverts public expenditure and aid that could have been used to repair their properties and infrastructure. On the other hand, it forces them to bear the costs of debris removal, rehabilitation, and basic service provision.

Thirdly, it perpetuates war economy practices. The entire cycle, which begins with the destruction of properties, looting, and displacement of residents, and continues with the manipulation of the supply of construction materials, extortion of returnees, and seizure of land in low-income areas for lucrative urban development projects, is deeply enmeshed in the war economy. The cycle only serves the interests of those within the regime’s inner circle, including the military and security apparatus, warlords, and regime-linked businessmen. These same actors may have little interest in rolling back such profitable activities to allow an effective and transparent reconstruction process to take place, not to mention that the regime itself may lack the power to ensure that these actors comply with any reforms.

Whether this is a strategic choice by the regime or an opportunistic reaction to its crumbling authority and economy is not clear. However, what is evident is that the country lacks the necessary international consensus, as well as the essential security, political, and legal foundations to attract and effectively manage large-scale investments and reconstruction funding. Nevertheless, with the hope of boosting the return of refugees and internally displaced persons, some regional and external nations may start shifting toward early recovery and light rehabilitation activities. Although this shift is urgently needed, it comes with significant legal, security, and political challenges about which these countries must be fully aware. Rebuilding Syrian homes and infrastructure requires not only financial resources but also an effective, accountable, and transparent approach.

Remaining realistic about what can be accomplished, and acknowledging that a total bypass of the regime is currently not possible, the only way forward is through political negotiations with Damascus to enhance the operational environment before any funds are allocated. This process should include depoliticizing aid and ensuring unconditional access to light rehabilitation and early recovery assistance for all Syrians, including those in the northwest and northeast regions.

While U.N. agencies and INGOs can primarily handle the rehabilitation of public facilities and the removal of debris from main streets, housing rehabilitation can be directly undertaken by residents through financial assistance provided by INGOs. To enable an effective and equitable process, three key areas related to the operational environment must be improved:

-

Giving a greater role to organizations, civil society actors, and representatives of local communities in selecting locations and beneficiaries;

-

Easing and enhancing the security and bureaucratic procedures involved in obtaining permits and construction materials; and

-

Ensuring the security of properties, protecting them from looting or confiscating, and safeguarding their owners against arbitrary detention and extortion.

All of this is certainly easier said than done, though operating under the status quo will not only squander donors’ funds, but also perpetuate regime corruption and its war economy. Upholding two fundamental principles is imperative: The burden of reconstruction must not be placed on the shoulders of Syrians, and Assad and his associates should not be rewarded with funding to rebuild the damage that they themselves caused.

Munqeth Othman Agha is a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Syria Program, a doctoral student at the School of International Studies, University of Trento, and a researcher at the Syrian Memory Institute (Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies). He has previously been published by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and Institute of International Affairs (IAI).

Photo by AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.