This series explores the threat posed by the rise of ISIS to Asia, particularly Southeast Asia, and efforts that the governments of the region have taken and could/should take to respond to it. Read More ...

The militant jihadi movement has been growing steadily in Malaysia since the early 1970s. The origins of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) can be traced to Seremban, Malaysia, where Abu Bakar Ba‘asyir began laying the groundwork for the organization in the early 1980s. When he spearheaded the formal establishment of JI a decade later, Ba‘asyir created four mantiqis (bases) covering Malaysia and Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines, Indonesia and Sulawesi, and Australia and the Papuas.[1] JI went on to serve as a platform for international terrorist groups. Al-Qa‘ida and, more recently, the Islamic State (ISIS) have tapped into JI’s organizational structure in order to increase their influence in Southeast Asia. This essay explores this ongoing synergy between regional and international militant groups in Malaysia, and examines the government’s continued failure to contain the spread of extremism.

Islamization in Malaysia: A Brief History

The New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1969 marked the beginning of concrete steps towards Islamization. Although the NEP was put forward in response to the May 13, 1969 race riots, the policy was basically a radical affirmative action program that sought to empower and improve the socioeconomic position of the majority Malays (Bumiputras, or indigenous people, about 60 percent of the population), who are constitutionally defined as Muslims. By the Mahathir Mohamad era (1981-2003), many Islamic-centric institutions had already been established, and under his watch this process continued to gather momentum.[2]

Mahathir’s successor, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (2004-2009) promulgated “civilizational Islam” (Islam hadhari), which “called for values and principles of a state to be compatible with Islam, without necessarily forging a state which incorporates the Islamic legal framework …”[3] Badawi nonetheless increasingly acceded to political pressure from Malay Islamic groups during his tenure in order to appear more “Islamic” than his opposition.[4] This political approach created an environment in which radical and extremist groups flourished. Commenting on the United Malays National Organization, the party that has led Malaysia’s ruling coalition since 1957, Patricia Martinez notes that the “UMNO has embarked on a da‘wa (mission) to Islamicize itself, the government, and the nation.”[5] Little did the Mahathir and Badawi administrations realize that their policies were helping to create an environment in which militant jihadism could thrive—to the extent that it now threatens national security.

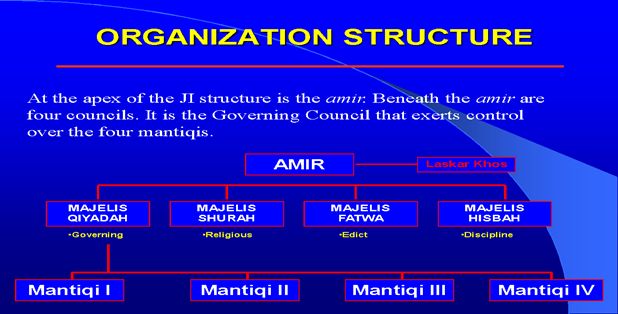

Formally established in 1993, JI became the leader among militant Islamic groups seeking to establish a “caliphate” in Southeast Asia. JI was headed by the amir, and below him were four councils: the Majelis Qiyadah (Governing), the Majelis Shurah (Religious), the Majelis Fatwa (Edict), and the Majelis Hisbah (Discipline). The governing council exerted control over the four mantiqis in the region. The organization also included a special operations unit, Laskar Khos. [6]

Laskar Khos (or Unit Khos, as it is commonly known) was established by Abu Bakar Ba‘asyir to carry out assassinations and bombings. It is a well-equipped and well-trained unit similar to military special operations teams conducting close quarter battle operations, and it has carried out all of the major JI attacks within the region since 9/11. The leader of Unit Khos reports directly to the amir, bypassing the command structure. The members of Unit Khos are said to be drawn from individual terrorist cells depending on the nature of the assignment.

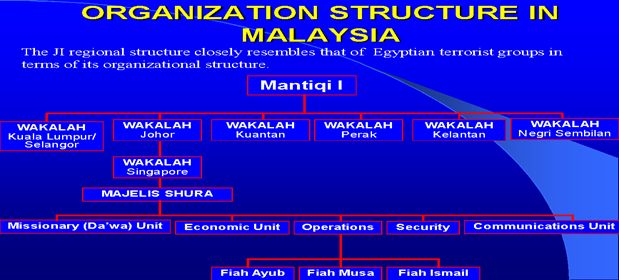

The leaders of JI designated Mantiqi 1 (Malaysia and Singapore) a non-operational cell that would focus on fundraising, money laundering, recruitment, and planning.[7] However, JI did attempt attacks on two U.S. visiting delegations from the National Defense University en route to Malaysia’s administrative capital of Putrajaya in 2004 and 2007. These attempts were foiled by Malaysian counterterrorism experts, in cooperation with U.S. authorities. A C4 explosive was also found under the Malaysia-Singapore Bridge by Malaysian and Singaporean authorities.[8]

Jemaah Islamiyah Organization Structure: Source IACSP SEA

Malaysia’s Mantiqi 1 cell actively recruited both Indonesians and Malaysians. In the early stages, JI’s recruitment process in Malaysia concentrated on local institutes of higher learning. The estimated number of JI members during the early 1990s was 200. In addition to recruitment, JI gave Mantiqi 1 four other major responsibilities:[9]

- To serve as a conduit between al-Qa‘ida and JI.

- To liaise with Kumpulan Militant Malaysia in Malaysia.[10]

- To establish front companies that could be use to channel funds.

- To assist in establishing Mantiqi 4 in Australia.

Jemaah Islamiyah’s Organization Structure in Malaysia: Source IACSP SEA

JI’s Malaysia cell had international links to al-Qa‘ida through its associations with al-Qa‘ida in Pakistan (AQP) as well as splinter groups within Southeast Asia such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), and the Southern Thailand Patani groups. International recruitment and operations were conducted in Malaysia for more than a decade. It may be noteworthy that some of the 9/11 terrorists were in the city of Petaling Jaya, Malaysia prior to the attacks, and that the original planning of 9/11 took place in Petaling Jaya before the attackers transferred their base to Germany.[11]

The Rise of ISIS and the Malaysian Response

Although the Singaporean government has succeeded in neutralizing the Singaporean component of Mantiqi 1 since 9/11, the Malaysian government’s efforts to clamp down on JI—and extremist groups in general—have been hampered by a lack of political will. This deficiency appears to stem mainly from politicians’ desire to accommodate the perceived religious sensibilities of the country’s majority Muslim population.

At the very height of the war on terrorism, with the assistance of the United States, Malaysian authorities did achieve moderate success in diminishing the threat posed by JI in Malaysia; however, the complacency of political powers within the country allowed for radical and extremist elements to survive as “sleeper cells,” waiting for the right moment to reemerge. JI of Indonesia has now declared support for a new caliphate in Indonesia and has announced its close links with ISIS.[12] Ominously for Malaysia, with this declaration, JI’s mantiqis have now been reactivated.

As in Indonesia, ISIS’s supporters in Malaysia are largely former JI members, already organized in cells networked according to JI’s preexisting structure. ISIS’s recruitment in Malaysia, targeting Muslim youths, is similar in nature to that of JI’s long-running recruitment efforts, with the additional and very potent element of social media. Like al-Qa‘ida before it, ISIS is attempting to gradually absorb what remains of JI into its wider structure. ISIS has adopted JI’s global Salafi ideology in its quest to garner support and new recruits,[13] while JI will put itself at the disposal of ISIS in return for funding, training, and cooperation in carrying out attacks within Southeast Asia. An estimated 50 to 100 Malaysians have now traveled to fight with ISIS on the battlefields of Iraq and Syria.[14]

Current social media and websites are the main recruitment tool for ISIS. However, by concentrating solely on shutting down these channels, Malaysian authorities have missed opportunities to counter ISIS propaganda through mainstream propaganda of their own that emphasizes the importance of democratic values. Efforts to shut down ISIS’s recruitment websites are costly and ineffective; for every site that is successfully shut down, two or three new ones appear.[15] The government’s preoccupation with these websites diverts its attention and resources from more creative and proactive measures.

Since October 2014, Malaysian authorities have warned that ISIS constitutes a major threat to Malaysia and that non-Muslims in Malaysia are likely to be targeted by ISIS militants returning from Syria.[16] This potential development raises real security concerns for Malaysians of minority races and religions and threatens the country’s multi-ethnic, multi-religious identity.

The September 2013 Pew Global Attitudes Survey reported that 27 percent of Muslims in Malaysia feel that suicide bombings can “often or sometimes” be justified in defense of Islam.[17] In other words, a significant minority of Malaysians hold viewpoints that overlap to some degree with those of extremist groups. If it indeed exists, this level of tacit acquiescence to violent acts—along with the organizational platform provided by JI—could permit militant groups to flourish in the coming years, especially if the government fails to take effective preventive measures.

Conclusion

The fact that Malaysia has chosen not to take part in the anti-ISIS coalition stems from concerns about security threats from indigenous extremists. It is hardly surprising that these threats remain a higher priority than events in Syria and Iraq;[18] indeed, the threat of terrorist groups (whether domestic, regional, or international, or a complex synergy of the three) operating in Malaysia is significant. A lack of political will remains the primary obstacle to countering these groups, but efforts to halt the spread of extremism face many other challenges, such as inadequate border and immigration controls, insufficient government resources, uncontrolled corruption, and poor security consciousness. Therefore, it is entirely possible that ISIS will continue to be successful at inspiring and mobilizing Malaysian Muslim youths.

[1] International Association for Counterterrorism and Security Professionals, South East Asia Region (IACSP SEA) Centre for Security Studies, database library, www.iacspsea.com.

[2] The NEP, which Mahathir inherited from his predecessors, was originally intended as a goodwill gesture toward Bumiputras and was aimed at improving their economic position through equity targets in areas such as corporate ownership and university admission. However, under the Mahathir administration the NEP evolved into an “Islamicize Malaysia” policy. Importantly, in its first few years, the Mahathir administration launched a number of other initiatives that emphasized Islamization, including the founding of a multitude of Islamic institutions, such as the Islamic Bank and the Islamic Economic Foundation; the construction of massive mosques and the establishment of Islamic universities; and the formation of Islamic think tanks. In addition, the government created an Islamic Consultative Body (ICB) and adopted an “Inculcation of Islamic Values” policy that articulated a model of corporate Islam. See, for example, Zachary Abusa, Militant Islam in Southeast Asia: Crucible of Terror (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2003), 51.

[3] Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid, “The UMNO-PAS Struggle: Analysis of PAS’s Defeat in 2004,” in Malaysia: Recent Trends and Challenges, eds. Saw Swee-Hock and K. Kesavapany (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asia Studies, 2006), 116.

[4] Werner Ende and Udo Steinbach, eds., Islam in the World Today (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010), 378.

[5] Patricia Martinez, “The Islamic State or the State of Islam in Malaysia,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 23, 3 (December 2001).

[6] IACSP SEA database library.

[7] Ibid.

[8] US Defense Department official.

[9] IACSP SEA database library.

[10] Lt. Col. Sani Royan, Deputy Director, Malaysia, International Association for Counterterrorism and Security Professionals-Centre for Security Studies, and former Malaysian Armed Forces Intelligence Officer, Department of Intelligence Services Division.

[11] IACSP SEA database library.

[12] Navhat Nuraniyah and Sulastri Osman, “Impact of ISIS’ ‘Caliphate’ on Indonesia’s Militants,” The Straits Times, July 11, 2014, http://www.straitstimes.com/news/opinion/more-opinion-stories/story/impact-isis-caliphate-indonesias-militants-20140711.

[13] IACSP SEA database library.

[14] “Five Suspected Islamic State Militants Return,” News Straits Times (Malaysia), November 8, 2014, http://www.straitstimes.com/news/asia/south-east-asia/story/five-suspected-isis-militants-return-malaysia-three-them-arrested-20.

[15] Andrin Raj, http://www.Fz.com.

[16] See, for example, Shannon Teoh, “Malaysia Tables White Paper on Islamic Militancy,” The Straits Times, November 26, 2014, http://www.straitstimes.com/the-big-story/asia-report/malaysia/story/malaysia-tables-white-paper-islamic-militancy-says-new-anti.

[17] “Muslim Publics Share Concerns about Extremist Groups,” Pew Research Global Attitudes Project, September 2013, http://www.pewglobal.org/2013/09/10/muslim-publics-share-concerns-about-extremist-groups/.

[18] Kym Bergmann and Jean-Michel Guhl, “Asia Unrepresented in Anti-ISIL Coalition,” Defence Review Asia, November 2014, 8.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.