As the Syrian civil war—at least from Damascus’s point of view—enters its final stages, the Assad regime will likely begin looking beyond narrow military goals, and focus more on the socio-economic stability and viability of its captured statelet. After six years of war, the Syrian regime finds itself in a disastrous fiscal situation, unable to shift funds to meet humanitarian and stabilization needs. Further expansion of what past analysts have oversimplified as “useful Syria,” without the means to sustain itself, could lead the Syrian regime either into domestic troubles—nominally loyalist militias and criminal gangs already prove a challenge to the government—or into even greater dependence on outside sponsors and accompanying compromises on sovereignty and leverage. Those interested in future stability, migration, and foreign expansion in Syria ought to pay close attention to how Assad balances fiscal constraints, military plans, and sovereigntist ambition.

In the Fiscal Trap

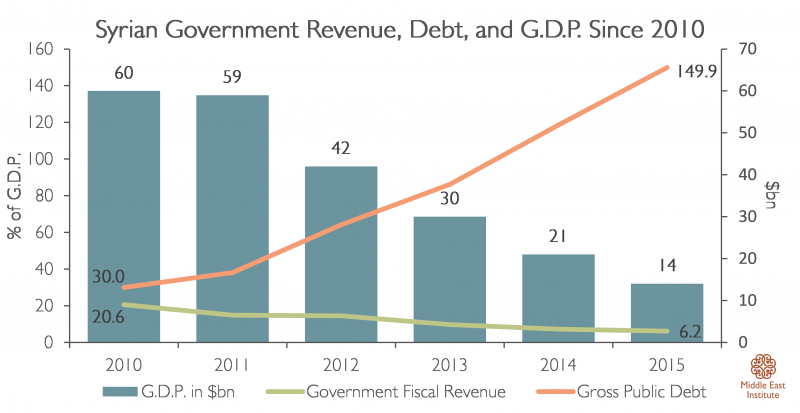

In recent months, as international actors have slowly moved toward reconstruction planning for Syria, the full scale of the economic challenge facing Damascus is becoming clear. The U.N. reports that government fiscal revenue collection has declined by almost 94 percent from 2010 to 2015. In absolute terms, this would add up to an accumulated war impact G.D.P. loss of $226 billion 2010 dollars—or roughly four times the country’s G.D.P. that year.

Source: IMF

Yet, despite imploding finances, the Assad regime early-on identified its ability to uphold basic public services and administration as essential to its claim of national sovereignty, as well as its more recent line of argument, being the only faction with the institutions and bureaucracies necessary for effective governance, even in territory far from nominal state control. The regime has poured all its resources into meeting public sector salaries and sustaining military expenditures. Thus, the Syrian regime severely cut nominal subsidies (though they still make up a major share of the budget) and essentially halted capital investments (now amounting to a mere one percent of G.D.P.) in infrastructure and public goods, while at the same time expanding current expenditures, primarily salaries and benefits, as percentage of G.D.P. At multiple times, the Syrian government has issued pay increases to control rampant inflation, but was forced to offset these through revenue-generating measures (taxes and subsidy cuts) that largely blunted any impact for ordinary Syrians.

The increasing divergence between its ability to collect money (its single largest dependable source of tax revenue is two telecommunications companies), and the cost of the ongoing war effort drove Damascus into debt—now estimated to stand at 150 percent of G.D.P. In 2015 alone, the budget deficit stood at 86.3 percent of total expenditures. With Iranian credit lines unable to bridge that gap, the Syrian government has been borrowing from its own captive Central Bank, thus further debasing the already teetering Syrian pound.

Tension between Short and Long-Term Imperatives

Absent sudden peace and reconciliation, and with economic decline merely slowing, how can the Syrian regime avert fiscal implosion without fundamentally disrupting its own war effort?

Before the war, Syria’s economy and its government’s public finances heavily relied on capital-intensive manufacturing and extractive sectors. In 2010, oil revenue alone, which has essentially ceased, was responsible for 26 percent of Syria’s state budget, 6 percent of G.D.P., and 37 percent of export value. The same year, domestically produced gas was already used to cover 60 percent of Syria’s electricity needs. The destruction of capital intensive sectors is the primary reason for the regime’s fiscal predicament. After six years of war, agriculture has replaced extractives and manufacturing as the largest non-service constituent parts of Syrian G.D.P., doubling from 20 percent to 39 percent, despite contracting by 41 percent itself. In effect, the country has turned into a partially agrarian, bureaucratic, and martial economy—discounting black markets.

Yet, the regime cannot easily divert funds from current expenditure toward rebuilding industry. The estimated cost of rebuilding Aleppo’s main power plant alone ($1 billion, according to the World Bank) approaches the regime’s annual tax revenue. And every dollar cut from salaries could potentially create a backlash and fuel further instability. In a country with upwards of 75 percent unemployment in the private sector and awash with weapons, normalization is no easy matter. Already, the Syrian regime is struggling with rampant crime, extortion, looting, and smuggling as even loyalist militants have begun to live off the land. These cannibalistic networks have in fact become constituent parts of the Syrian war economy. Trade data shows that, despite a 92 percent decline in overall exports, the volume and value of copper and alloys—commonly looted from factories and houses—actually increased over the course of the war, with almost all of which went to a single destination in Egypt. The pressures of the Syrian civil war have driven the already corrupt Syrian state deeper toward its own proclivities.

Compromises—Foreign Influence

In this context, recent moves by the Assad regime in the east make sense beyond the common “Iranian land bridge” narrative. Considering the regime’s tenuous fiscal position and import restrictions, Assad’s government is hard-pressed to reconstitute core sectors of Syria’s infrastructure on the cheap. Auctioning off stakes in the now-destroyed sectors of the economy to foreign stakeholders in return for investment, military support, and a cut of the revenue is preferable to turning to Western donors or private financiers. For example, a recent announcement saw a Russian company gain a 25 percent stake in Syria’s oil sector in return for investment in recovery, security, and other areas. Similar deals have been struck with Russia and Iran in other sectors as well, such as the gas field recovery and exploration, or phosphate mines, which have both Russian and Iranian stakeholders. Permitting expansive Russian and Iranian roles in these sectors could further bolster exports of raw commodities to these countries, supporting the regime’s weak foreign accounts position.

The past year has also seen the regime’s foreign backers increasingly take over Assad’s current expenditure obligations. The much-publicized Fifth Assault Corps has been publicly known to be built and sustained from Russian coffers. More interestingly, Iran appears to have slightly shifted strategies, now increasingly financing its own Syrian-national militias directly. A series of documents leaked earlier this spring listed more than 86,000 Syrian nationals as members of the “Local Defense Forces” militias, whose salaries and—importantly—martyrs payments are covered by Tehran.

The latter project especially straddles the line between lifting weight off Assad’s shoulder, and carving a narrower sphere of influence from the carcass of a regime that is unlikely to become economically self-sufficient within decades. Instead of getting sucked into the larger problem of stabilizing Assad’s statelet, Iran and others may prefer to selectively invest in clients and infrastructure conducive to their narrower national interests, leaving the larger rebuilding part to the international community.

Conclusion

For the Syrian regime, there are no easy or obvious answers. Fundamentally, Damascus is driven by the ambition to reconstitute its sovereignty across the country. At the same time, broke and enfeebled, it must balance competing constraints and imperatives to avoid leaving a vacuum at home that may eventually provide the opposition a second opening to challenge it among those Syrians still remaining in government-held territory.

As usual, it is ordinary Syrians who have been bearing the cost of Assad’s brutal war and who will suffer the eventual economic adjustment. Their resilience, and the international community’s discipline in doling out stabilization aid to a regime that has wasted its people’s lives and wealth to—likely successfully—cling to power, will prove decisive. In the end, according to one sophisticated World Bank economic model, the objective damage to capital inputs and human casualties barely accounts for a twentieth part of the collapse of the Syrian economy. The real multiplier and true source of Syria’s economic destitution is the continuing destruction of its social fabric. Even loyalists must be skeptical about whether Bashar al-Assad will be able to address that issue.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.