Relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia have been in the spotlight over the past six months, following the March 2023 China-brokered agreement to normalize ties seven years after they were cut off in 2016. The connections between Tehran and Riyadh go back much farther, however. Indeed, as a new archival report on Iranian-Saudi diplomatic history makes clear — the first publication to collect, translate, and contextualize Iran’s Persian-language archives on bilateral relations during the period from 1913 to 1979 — they even predate the founding of the current Saudi kingdom in 1932. Below are a series of excerpts from the report, highlighting key themes that emerge from the archives. While much has changed over the past century of relations between Riyadh and Tehran, many of these themes continue to resonate today.

Resolving tensions in the Gulf

Iran’s assertions of authority over the southern Gulf region, by virtue of having controlled parts of the area before the Ottomans arrived in the 16th century, were challenged by Abdulaziz Al Saud. Known as Ibn Saud in earlier literature, he emerged to unite tribes in the Arabian Peninsula and establish the modern state of Saudi Arabia in 1932. A decade earlier, he concluded the Treaty of Muhammara with the British to demarcate the Gulf boundaries of his newly-established Sultanate of Najd and its Dependencies (1921-26). In 1924, his troops, known as the Ikhwan (or “Brethren”), advanced toward the Hijaz in western Arabia. Meanwhile Iran failed to push forward its claims over Bahrain, and the islands of Abu Musa and Greater and Lesser Tunb, through the League of Nations in 1927. Abdulaziz established the Kingdom of Hijaz and Najd and Its Dependencies, and formally recognized Bahrain, prompting Iran to withhold recognition for his kingdom and demand the return of Bahrain to “Persian domain and authority.”[1] In February 1928, he reached out to Iran to sign a mutual security pact.[2] Iran rejected the idea and substituted it with a nonbinding promise of nonaggression.[3]

When Britain announced its intention to withdraw from the Gulf by 1969, Iran consulted frequently with Saudi Arabia, and agreed to grant Bahrain its independence in December 1971. But it stationed military forces in the Gulf islands that it contested with the United Arab Emirates. Saudi Arabia expressed regret, but it did not take a stand against Iran on the issue before the U.N. Iran had earlier refused to recognize the new Yemeni regime backed by Egypt (despite the U.S. decision to do so in December 1962), offered arms to Saudi Arabia, and encouraged Washington to do the same to help it protect its borders against hostile Yemeni forces.[4]

Promoting statecraft

Abdulaziz invited Iran to send a fact-finding mission to inspect the conditions on the ground in the Hijaz, home to the cities of Jeddah, Makkah, and Madinah.[5] Iran’s consul general in Syria, Habibollah Hoveida, met with Abdulaziz and reported that:

“Ibn Saud informed the residents of Makkah … that if they obey the rules that the Al-Saud seek to establish, they will be protected …. [and] sent a letter to the residents of Jeddah, saying that he was keen to resolve things peacefully.”[6]

Abdulaziz sent a telegraph to Iran to congratulate Reza Shah when he established the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925. Hoveida conveyed Reza Shah’s message of friendship to Abdulaziz:

“Express gratitude … offer a reminder that … Iran has absolute interest toward Madinah and Makkah, and a desire to establish … relations with … Hijaz.”[7]

Abdulaziz received Hoveida in the fort palace of Qasr al-Khuzam on the outskirts of Jeddah, and the latter reported that:

“Ibn Saud … sat me next to him as a sign of respect for Iran. He read a prepared note in Arabic, stood up as I started reading the letter dispatched by Reza Shah which was wrapped in silk and handed … in a silver tray. … Ibn Saud took care opening the letter … before handing it back to me to read out loud, after which drinks and refreshments arrived to celebrate a new union.”[8]

Abdulaziz sent a delegation to Iran in 1926 to seek recognition,[9] and Reza Shah dispatched a letter in response in 1928, outlining Iran’s terms. After negotiations, Iran granted recognition to the “Government of Hijaz and Najd” on Aug. 13, 1929:

“We are pleased to inform you that the Imperial Government of Iran has as of the date today extended its recognition to the Government of Hijaz and Najd.” [10]

This led to the conclusion of a Friendship Treaty signed in Iran, exchanged in Jeddah, and recorded in the archives of the League of Nations.[11]

Addressing religious divides

Iran’s Shi'i clerics pressured Tehran to help facilitate the hajj in Makkah and Madinah. Abdulaziz negotiated with Hoveida in Makkah about the issue. Hoveida conveyed a message on behalf of Iran, to protect the Kaaba at the center of the Grand Mosque, while Abdulaziz conveyed the following message to Iran:

“The … Sultan is … keen to provide the welfare of and comfort for the subjects of your Esteemed Government [to perform the hajj].”[12]

Abdulaziz proceeded to invite Iranian clerics to visit the Hijaz.[13] But Iran, which had placed a three-year ban on performing the hajj during the battle of the Hijaz, objected to Ikhwan action to remove the markings from graves in order to discourage acts of worship of the dead. The Ikhwan had removed the markings from graves in Jannat al-Baqi cemetery in Madinah, where Shi'i imams of the Ahl al-Bayt — members of the house of the Prophet Muhammad and his progeny — are buried. In a statement, Iran declared:

“Recent actions happened … that [brought] a moment of reflective pause, resulting in Iran’s government finding it unacceptable to accept Ibn Saud’s invitation.”[14]

Hoveida spent three days in Madinah and he confirmed that the Ikhwan had removed the markings from graves in the cemetery of Jannat al-Baqi.[15] Reports sent to Iran after it lifted the hajj ban showed that pilgrims were restricted from visiting the graves:

“Officers of the Hijaz Government in Madinah … barred pilgrims from freely visiting the holy … imams buried in baqi.”[16]

In 1930, Abdulaziz dismantled the Ikhwan and sent a message to Iran:

“I tell you unequivocally … I will protect the Haramain Sharifain [i.e. the holy sites of Makkah and Madinah] with my life and wealth and children.”[17]

Balancing ties with US and Israel

Iran’s oil nationalization crisis to end British control of the Iranian oil industry was followed by a British- and U.S.-backed coup in 1953 to overthrow Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Saudi Arabia helped Iran navigate the crisis by trading with the country despite a Western boycott. Saudi Arabia also opposed the 1955 Baghdad Pact, launched to connect the U.S. geographic spheres of influence in the Middle East, although Iran joined the pact.

Source: Pahlavi Dynasty, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons

The 1973 oil boom, the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli War, and the Saudi boycott of oil sales to the West for backing Israel, helped Iran and Saudi Arabia expand ties.[18] But Iran’s drive for higher oil prices challenged Saudi Arabia’s plans to gain ownership from the U.S. of a fourth of its crude oil operations at Aramco (the Arabian American Oil Company, now known as the Saudi Arabian Oil Company). After lengthy negotiations, Riyadh gradually gained control of Aramco, and agreed to lower oil prices to help the U.S. economy.

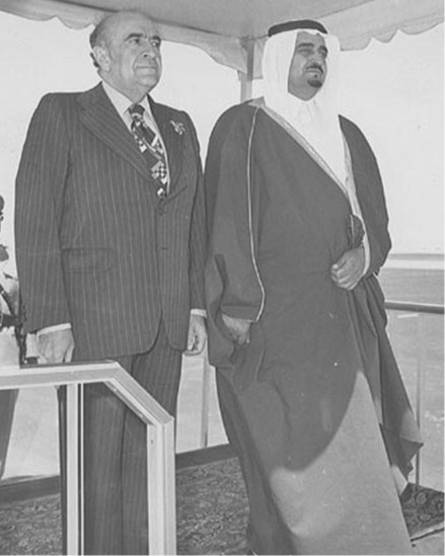

Saudi Arabia encouraged Iran to halt exports to Israel. Saudi newspapers even listed Jewish-owned businesses in Iran and urged Arabs to cease trading with them.[19] Iran had granted de facto recognition to Israel in 1950. In 1976, it raised the issue of Arab-Israeli normalization when the Saudi leader, King Khaled bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, traveled to Tehran.

In a joint press conference, Khaled showed no reaction when the Iranian leader, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, told reporters from the Arab world that normalization with Israel could be beneficial to the region:

“Should Arab countries decide to recognize Israel … they will not face a loss, because Israel’s existence is an undeniable reality.”[20]

Emerging more confident from the oil crisis, Saudi Arabia attempted to conclude a region-wide Gulf security agreement that included Iran in 1977. In July 1978, Saudi Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdulaziz Al Saud traveled to Iran to seal a regional security deal. By that autumn, however, the shah had lost his grip on power. He left Iran, never to return, on Jan. 16, 1979.

Conclusion

Relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran took a sharp turn for the worse under the Islamic Republic. Riyadh perceived Tehran’s revolutionary brand of Islam as a direct threat to the religious legitimacy on which the kingdom and the Al Saud dynasty were based. The dynamic grew increasingly adversarial, prompting Riyadh to provide support to Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq War from 1980-88. Over the subsequent decades, tensions between the two regional powers would continue to ebb and flow, ultimately resulting in the cutoff in ties in 2016.

Following the Saudi-Iran normalization agreement in March 2023, the longevity of this most recent chapter in the century-long history of bilateral relations between Riyadh and Tehran remains uncertain. Only time will tell what the future holds, but many of the key themes that emerge from the newly translated Persian-language diplomatic archives, such as tensions over efforts to assert regional dominance, the impact of religious divides, and differences over perceptions of actors like the U.S. and Israel, continue to define Saudi-Iranian relations today.

The full version of the report “Archival History of Iran’s Diplomatic Relations with Saudi Arabia, 1913-79” is available for purchase here.

Banafsheh Keynoush is a scholar of international affairs, a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Iran Program, and a fellow at the International Institute for Iranian Studies.

Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Endnotes

[1] Saeed Badeeb. Saudi-Iranian Relations: 1932-1982 (London: Center for Arab Iranian Studies and Echoes, 1993)),pp. 53, 222, citing al-Aidarous, al-alaqat al-arabiah al-iraniah, and “British Embassy in Tehran to London (PRO), Telegraph no. 1062/156”.

[2] “Letter of Iran’s Vice-Regent in Egypt, Documents of Iran and Saudi Arabia,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 44, file no. 19, May 1928.

[3] Badeeb, p. 49, cited from Telegram No. E 6322/3704/91, from Mr. Bond to Mr. Butler (Public Record Office London), dated November 10, 1929.

[4] “Pilot and Remains of Iranian Airplane Returned,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 73, no. 21893, 30/9/2535; Saeed Badeeb. Saudi-Egyptian Conflict Over North Yemen (Boulder: Westview Press, 1986), pp. 39, 56-57.

[5] “Meeting of Habibollah Hoveida with Malak Abd al-Aziz,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 29, no. 108, khordad 8, 1309.

[6] “Notice to Residents of Jeddah from Abd al-Aziz Al Saud,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 7, no. 115, rabi al-thani 24, 1343.

[7] Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, telegraph no. 588, container 30, file 1, dei 29, 1304 sh.

[8] “Meeting of Habibollah Hoveida with Malak Abd al-Aziz”.

[9] “Letter from Habibollah Hoveida to Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran,document 254, dei 24, 1304/January 14, 1926.

[10] “Relations Between Iran and Saudi: Agreements of Iran and Hijaz,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 13, file 113, 1308.

[11] “Hoveida’s Report to the Foreign Ministry,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 50, file 71/189, 1930-1931.

[12] Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 30, file 2, document 127, nisan 12, 1925.

[13] “Invitation of Ibn Saud to Iranian Ulema and Government,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 6, no. 126, aghrab 20, 1303.

[14] “Declaration of the Government of Iran,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 30, document 22, file 3, tir 1, 1305.

[15] “To the Residents of Muslim Countries and the Muslim Public, it is Declared,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 22, tir 1, 1305.

[16] “Esteemed Official of the Embassy of the Great Government of Iran the Blessed,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 24, no. 43, muharram 28, 1347.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 53, file 45, 1332; Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, telegraph no. 3106, container 19, file 12/1, azar 17, 1350.

[19] “Air Transport Agreement Between Iran and Saudi Arabia” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, container 29, file 11, 1338/195; “Use of the Unclear Name of ‘Arabian Gulf’ on Saudi Arabia’s Radio,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 60, khordad 10, 1335/ May 31, 1956.

[20] “Visit Between Shah and Malak Khaled,” Archives of the Foreign Ministry of Iran, document 71, telegraph no. 302, khordad 7, 1335.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.