This week's briefing on recent news and upcoming events in the region featuring Charles Lister, Randa Slim, Jonathan M. Winer, Alex Vatanka, Marvin G. Weinbaum, Robert S. Ford, Mirette F. Mabrouk, and Syed Mohammad Ali.

Constitutional Committee talks highlight Syria’s spiraling COVID crisis

Charles Lister

Director of Syria Program and Countering Terrorism & Extremism Program

After much hype last week from the UN, a new round of talks within Syria’s Constitutional Committee looked set to close before it even started, when three and later four of the 45 participants were confirmed on Monday to be infected with COVID-19. All four participants had traveled to Geneva from Damascus on the same flight. Two represented the regime team and one each were from the civil society and opposition blocs. A UN statement on Monday confirmed the talks were now “on hold.”

That no Constitutional Committee meetings had been conducted for nine months had been attributed to the global pandemic, but the UN appears to have underestimated the scale of the COVID crisis, particularly within regime-held areas where COVID-19 is spiraling, especially in Damascus and more recently in Aleppo. UN Special Envoy Geir Pedersen had insisted on Friday that all 45 participants would be pre-tested before travel to Geneva and tested again on arrival, but somehow three positive cases slipped through the cracks.

The prospect of the Constitutional Committee’s work being postponed again poses troubling questions about the UN and the international community’s efforts to keep at least some movement going on the only political track still alive. After nearly a year of high-level closed-door talks between the U.S. and Russia, some had expressed hope that Moscow might demonstrate some progress in coercing the regime to engage more constructively. Whether that hope was misplaced or not may now be academic.

Although Syria’s regime — backed up by the World Health Organization — has admitted to a little over 2,000 cases of COVID-19 infection and 83 deaths as of Aug. 21, independent modeling has estimated that there are as many as 100,000 active infections in Damascus alone. Large mass burial grounds are expanding outside the capital and some brave doctors have begun speaking out anonymously, seeking to ring alarm bells. The deputy director of health in Damascus claimed three weeks ago that there were 112,500 COVID cases in Damascus and its countryside and an Aleppo-based doctor now says hospitals are “running out of body bags.” With insufficient medical facilities, an economic crisis caused by financial instability next door in Lebanon deterring social distancing and lockdown measures, and secret police intimidating health care workers, the COVID-19 crisis is clearly spiraling out of control in Syria. As that reality kicks in, little else may matter.

Mr. Kadhimi comes to Washington

Randa Slim

Senior Fellow, Director of Conflict Resolution and Track II Dialogues program

Iraq is facing another summer of discontent and unrest. While Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi was being feted in Washington last week, Iraqi civil society activists were ambushed and gunned down in Basra. In reaction to these killings, a new wave of protests emerged in Iraq’s southern provinces, with protesters attacking political party and militia offices in Dhi Qar and the Iraqi Parliament’s office in Basra. In the Kurdistan region in the north of the country, demonstrators set fire to government and political party buildings in Sulaymaniyah and Halabja. In the past few weeks, similar protests have also been held in Duhok and Erbil provinces. People are protesting against the recent decision by the Kurdistan Regional Government to cut public sector salaries and impose austerity measures.

While the threshold for success was low, Mr. Kadhimi’s first trip to Washington as prime minister delivered few notable tangibles: a meeting with the U.S. president, meetings with congressional leaders, a second meeting of the U.S.-Iraq strategic dialogue, and announcements of a number of potential projects with U.S. energy companies. More importantly, the trip paved the way for another U.S. extension of sanctions waivers for Iraq to import gas and electricity from Iran, without which Mr. Kadhimi’s woes at home will only get worse. When asked about a U.S. troop withdrawal, both Iraqi and U.S. officials did not indicate a specific timetable, instead committing to the objective of an eventual U.S. withdrawal while relegating discussions about timing to a joint technical committee set to meet soon. Iraqi officials indicated that they discussed with their U.S. counterparts the need for a new framework for military cooperation between the two countries focusing on the Iraqi security services’ needs in training, capacity building, and intelligence sharing.

Dr. Ali Allawi, the Iraqi deputy prime minister and minister of finance who was part of the delegation visiting Washington, stated that the U.S.-Iraq relationship is currently in a state of “unstable equilibrium.” In order to move to a stable equilibrium, a national consensus over the future direction of Iraqi domestic and regional politics must be negotiated and agreed upon by the different Iraqi political parties and forces that are now contesting the political space, including the protest movement. Part of this contestation pivots around which geopolitical axis Iraq will be part of: that of the U.S. and its Arab allies, that of Iran and its Arab allies, or perhaps a third and as-yet-undefined multilateral regional arrangement that Baghdad can help shape over time. Another part of this contestation is about the political, security, and economic reforms Iraq must implement after years of poor policies and mismanagement of these sectors. It is only by pursuing these reforms that Iraq will be able to break the cycle of corruption, impunity, and bad governance that has plagued the country to-date.

As Hifter rejects Libyan cease-fire, renewed diplomacy is essential

Jonathan M. Winer

MEI Scholar

The Libyan cease-fire agreed to on Aug. 21 by the prime minister of the Government of National Accord (GNA), Fayez al-Sarraj, and the speaker of Libya’s eastern-based House of Representatives (HoR), Aguila Saleh, was intended to be a concrete step to halt the military conflict whose hot phase began on April 4, 2019, when would-be Libyan dictator Khalifa Hifter initiated a military campaign to conquer Tripoli, the country’s national capital.

The agreement was immediately supported by the UN, the U.S., and some of the major foreign actors supporting each side. But Hifter’s silence about the cease-fire raised the obvious question of whether he would honor it. On Aug. 23, that question was answered — in the negative, raising the further question of whether the military standoff over the central coastal city of Sirte and the south-central airbase of Jufra will hold.

Achieving a demilitarized zone around Sirte following a cease-fire would have had the positive benefit of reducing tensions, building confidence, enabling military talks between the GNA and the eastern forces, and creating space for renewed political talks aimed at holding national elections in March 2021. It also would have created some risk of spheres of influence becoming formalized, with Turkey holding sway in GNA-controlled areas, and Egypt, the UAE, and Russia maintaining influence in the areas controlled by Hifter and the Tobruk-based HoR. Some fear this could eventually result in a de facto partition.

Meanwhile, the GNA-Turkish military coalition has been continuing to build up their forces around Sirte amid intensifying efforts to create a demilitarized zone. A GNA-Turkish attack on Sirte risks a broadened and intensified conflict. To avert this, Egypt, Russia, and the UAE, the main supporters of Hifter’s Libyan National Army, as well as the U.S., UN, Germany, Italy, and others, have in recent weeks intensified their diplomatic outreach to counter the risk of war.

Given Hifter’s rejection of the cease-fire, should diplomacy fail to demilitarize Sirte by voluntary means, a near-term Turkish-backed assault on Sirte, Jufra, and Libya’s oil crescent to the east remains a real, and very dangerous, risk for the entire country, even as reporting suggests a resurgence of the presence of ISIS in its south.

Snapback sanctions and a possible Biden presidency: The view from Tehran

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Frontier Europe Initiative

Tehran appears very confident that the Trump administration will fail in its push to impose so-called “snapback” UN sanctions against Iran. The Iranians have good reason to think so too. The rest of the world, including the other four permanent members of the UN Security Council, do not see how the U.S. can legitimately ask for snapback sanctions on Iran as part of the 2015 nuclear deal when Washington left that same deal in May 2018. The general international consensus is that Washington’s pursuit of snapback sanctions is ultimately about dealing a fatal blow to the agreement. In that scenario, Iran will be forced to negotiate a new deal either with a second-term Trump administration or a Joe Biden presidency.

In Tehran’s eyes, Washington’s rationale for staying on this unwinnable course at the UN is also about achieving several secondary outcomes: signaling to U.S. allies in the Middle East that Washington’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran remains strong, keeping the psychological pressure on the Iranians, and undermining confidence in the Iranian economy. By now it is fairly certain that the Iranians will not negotiate with Trump, even if he is re-elected. To escape more U.S. pressure, the Iranians will simply be forced deeper into the arms of Russia and China. Even President Hassan Rouhani, whose hardline critics accuse him of being a dupe on the question of negotiating with Washington, appears busy burning all bridges to the Trump administration. “If anybody inside Iran thinks that this tyrannical [Trump] administration and their tyrannical policies are perpetual, they are wrong,” Rouhani said last week.

But even a Biden presidency will present its challenges for Tehran. Biden’s top foreign policy advisor, Tony Blinken, maintains that a President Biden would make the nuclear deal with Iran “longer and stronger.” This offer poses a dilemma for Tehran. Biden returning the U.S. into the nuclear deal would be a welcome step. But the idea of a deal that is “longer and stronger” suggests that Biden too wants a new deal with Iran that is broader than the 2015 agreement. It would be one that goes beyond merely agreeing on limiting Iran’s nuclear program; it would involve negotiations about what Washington’s considers Tehran’s other troubling behavior, including its regional policies. Biden’s demands would probably look similar to many of Trump’s, but his election would be a face-saving moment for the Iranians. To give such tough negotiations a fighting chance, Tehran needs to start recalibrating its position on the U.S. and show a willingness to broaden a possible dialogue with a Biden administration. So far, there is no sign of that.

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have their falling out

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director for Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

Over the years few countries have been bound so closely as Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Pakistani troops have been deployed for decades in defense of the kingdom, and in particular in protection of the royal family. Pakistan has also furnished generations of skilled and unskilled workers for a manpower-short Saudi economy. Saudi Arabia has in exchange regularly stood by Pakistan with financial assistance in times of economic distress. And over and above this worldly interdependence is their spiritual link: Saudi Arabia is revered by most Pakistanis as the guardian of Islam’s holiest sites.

So why should the relationship between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have recently turned sour? If the kingdom is important to Pakistan, there is something weightier, namely the birthright cause of Kashmir. Pakistan is desperate to keep the dispute over Kashmir alive, this despite India’s attempt to permanently remove it as a negotiable issue with the revocation last year of the former state’s once special status. Islamabad took deep umbrage when the Saudi-led Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) snubbed Pakistan’s call for a united Muslim front denouncing India’s action. An irate Saudi Arabia retaliated the best way it could — economically.

In 2018 when Pakistan found itself burdened with a number of onerous debt repayments, Saudi Arabia came to its rescue with a $6.2 billion aid package, $3 billion in a cash grant and the rest in the form of deferred loan payments on essential Saudi oil deliveries. But now the kingdom has demanded Pakistan’s early repayment of $1 billion and cooled on the idea of a two-year renewal of the oil payment arrangement. With the dollars to Saudi Arabia due at the end of the month, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi rushed off to Beijing last week to secure a $1 billion loan.

Six years ago, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia also had a serious falling out when the Islamabad government rejected a request to join a Saudi-headed military intervention in Yemen. Pakistan was able to largely mollify anger in Riyadh by offering instead to station additional troops within the kingdom “to protect its borders.” But the healing this time may be more difficult. Qureshi initially promoted the idea of convening a meeting of Islamic countries more sympathetic to discussing Kashmir. In Riyadh this was bound to be perceived as constituting a challenge to Saudi Arabia’s de facto leadership of the Muslim world. It also pointed to the possibility of Pakistan gradually shifting along with China toward a non-Arab alliance of Turkey, Iran, and Malaysia.

Far more likely is Pakistan’s patching up its differences with Saudi Arabia. The relationship remains too critical for both countries to allow to wither. The process has already begun. Prime Minster Imran Khan and Qureshi have walked back tough earlier statements and vigorously deny that the partnership with the kingdom is in trouble. Chief of Army Staff Qamar Javed Bajwa flew to Riyadh last week to mend ties and meet with Saudi military leaders. As a sign, however, that the rift may be slow in healing, Saudi Arabia has not relented on its repayment demand, and Bajwa, Pakistan’s most powerful figure, was denied an audience with the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

This article was co-authored by Hamid Safi, Sawera Khan, and Jack Stewart, research assistants to Marvin G. Weinbaum.

Tunisia: Technocrat cabinet or elections

Robert S. Ford

Senior Fellow

By the end of Monday Tunisian President Kais Saied should receive from his prime minister-designate, Hichem Mechichi, a cabinet list to submit to the Tunisian Parliament for the required vote of confidence. Winning that vote is still uncertain, however. Mechichi, with the encouragement of President Saied, filled the cabinet with technocrats without ties to political parties. Mechichi has urged the Parliament to vote for the cabinet’s program, not its personalities. Having a technocratic cabinet is dividing Tunisia’s already fractious Parliament. Notably, the largest alliance of liberal democrats split on Sunday over backing Mechichi’s list. One of the two Islamist parties in the Parliament pledged to vote against Mechichi’s proposed cabinet while Ennahda, the largest Islamist party, has expressed strong reservations but so far avoided a definitive rejection. Those critical of the cabinet list claim the technocrats would never get political backing for the tough economic and social reforms Tunisia needs.

If Mechichi’s cabinet fails to win the confidence vote, President Saied could dissolve this Parliament and call new elections. Opinion polling indicates the public holds political parties largely responsible for the economic slump, and voters could penalize many of the parties now in Parliament. Politicians castigating Mechichi’s cabinet list acknowledge that a new round of elections and more delays forming a permanent government will aggravate Tunisia’s problems. Notably, the Parliament speaker, Rached Ghannouchi, who heads Ennahda, speculated on Sunday that fear of new elections would lead a majority in Parliament to approve Mechichi’s list after all. Tunisia faces the prospect either of an approved cabinet without strong parliamentary backing or new elections by year’s end and in the meantime an interim government with limited capacity for dramatic reform steps.

Gridlock as GERD talks continue

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow, Director of Egypt program

This week sees the latest of an apparently interminable set of meetings between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). This round is part of an initiative sponsored by the African Union (AU) after talks between the three countries ground to a halt last year, with an initiative sponsored by the U.S. and the World Bank meeting the same ignominious fate in February of this year. This last set, in which the U.S., the European Union, and the AU Commission are all observers, doesn’t seem to be having any better luck.

This week’s meetings are geared toward removing obstacles, with the discussion of a preliminary report by the technical and legal teams on the heels of a meeting of the respective parties’ water and irrigation ministers. The report fine-combs points of both agreement and contention among all three countries, each of which had one member each of their legal and technical committees work on the draft. The expected outcome will be a tripartite report on the filling and operation of the dam on Aug. 28.

It’s likely to be a hard slog. Any final agreement will need to take into account the three earlier reports submitted to the AU, and the sticking points have not changed. There are two main points of contention. The first is whether a final agreement would be legally binding. While both Egypt and Sudan have made numerous concessions to date, they refuse to budge on this one. Their mutual nightmare is that in the event of a drought, Ethiopia’s hydropower needs will ensure that it doesn’t release the water both countries need. Approximately 50 percent of Sudan is desert while Egypt, one of the most water-poor countries in the world, is approximately 96 percent desert. It has minimal known ground water resources and no other renewable water sources, relying on the Nile for about 95 percent of its fresh water needs. The questions of how much water should be released in case of a drought, and on which dates, are integral to safety planning. Ethiopia has consistently refused any binding agreement, preferring a set of guidelines that it can adapt as needed. It has also reassured Egypt and Sudan that the dam’s operation would be based on “fair and equitable” water use and management. This has done little to reassure Egypt and Sudan, which have watched as Djibouti, Kenya, and Somalia all have been quite literally left high and dry by previous Ethiopian water and hydropower projects.

The other point of contention is the question of what happens if there’s a disagreement. Both Egypt and Sudan have asked for a legal arbitration mechanism, which Ethiopia has consistently refused, insisting on heads of state meetings. To date, such meetings have produced little other than photo opportunities and in the age of COVID, even those are now off the table.

There is, however, one new factor in this equation: Egypt’s rapidly improving relationship with Sudan. After three decades of steadily souring relations under former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, things are looking up. Faced with a mutual impending disaster, both countries have decided to rethink the relationship and take stock of their combined assets. Egypt, in particular, has stepped up its diplomatic efforts; Aug. 15 saw Egyptian Prime Minister Mustafa Madbouly descend on Khartoum with a bevy of his cabinet ministers. Madbouly’s meeting with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok resulted in a statement saying both countries had drawn up a “cooperation strategy” covering mutual investment, health care, education, and transportation. Of note to GERD watchers, power grid consolidation was also on the menu, as was an attempt to “restructure and develop” the Nile Valley Authority for River Navigation, a bilateral organization overseeing the transport of both goods and passengers on the Nile. A meeting was called for, pointedly to be held in Khartoum, to beef up the Authority. Most importantly for GERD watchers, the meeting produced a solid, mutual reiteration of their stand that any final agreement be legally binding and include an agreed upon dispute mechanism.

Sources say that this means that any drafts presented by Ethiopia are now likely to skew toward Sudan, in an attempt to tip the scales back in its favor. It’s unclear, though, how much of a dent in Ethiopia’s confidence in its negotiating position this is likely to have. Ethiopia needs the dam to power its development and its current government needs a win to deflect from its internal strife, both matters likely to strengthen resolve, rather than not.

Moralistic double standards on Kashmir and Xinjiang

Syed Mohammad Ali

Non-resident Scholar

Human rights and other forms of moralistic concern are readily evoked by different states within the international community to criticize the behavior of their adversaries. Yet such admonitions are often applied selectively. Such political cooption of moralistic principles is evident in American, Chinese, and Pakistani reactions to the ongoing problems in Kashmir and Xinjiang.

It is ironic that the United States under President Donald Trump has done more to draw attention to the plight of Uighur Muslims than any Muslim majority country. Several senior American officials have not minced their words while describing how Chinese authorities are using the excuse of rooting out religious extremism and terrorism to trample on the rights of Muslim Uighurs in the autonomous region of Xinjiang. Yet, the U.S. response to the revocation of the autonomous status of Kashmir by a Hindu nationalist government in India has been much more guarded. While the U.S. has called for easing a year-long lockdown in Kashmir and protecting the basic rights of Kashmiris, these calls are nowhere near as urgent as the concerns raised about Xinjiang. Many Pakistanis are disgruntled by this seeming double standard, which they describe as being compelled by the American need to woo India to counter-balance China.

For its part, China has been much more supportive of Pakistani concerns about the plight of Kashmiri Muslims than many Arab states, including Saudi Arabia. China’s concern for the rights of Muslim Kashmiris does not, however, translate into empathy for its own Muslim population.

It is not only China or America that seem to take a very selective view of upholding the human rights of a Muslim minority, but Pakistan itself.

Pakistan has in fact taken it upon itself to not only decry violations against Kashmiri Muslims but also growing Islamophobia within the West, yet it not only discriminates against its own religious minorities, but also remains mute on the issue of Uighur Muslims. In a trip to China this past week, Pakistan’s foreign minister reiterated support for the One China Policy (with regards to not only Xinjiang, but also Chinese actions in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Tibet).

Such cooption of human rights principles to selectively pursue realpolitik goals does a disservice to elevating concern for human rights above and beyond the pursuit of advancing national interests.

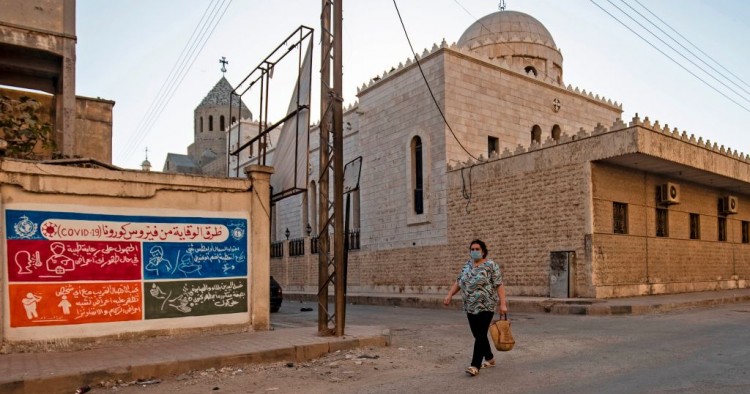

Photo by DELIL SOULEIMAN/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.