Contents:

- Turkey’s ruling AKP now faces the electoral scenario its opponents faced in 2002

- US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s quick weekend trip to the Middle East

- Will Iran willingly share Syria?

- UN meeting highlights ongoing frustrations and divisions over Afghanistan

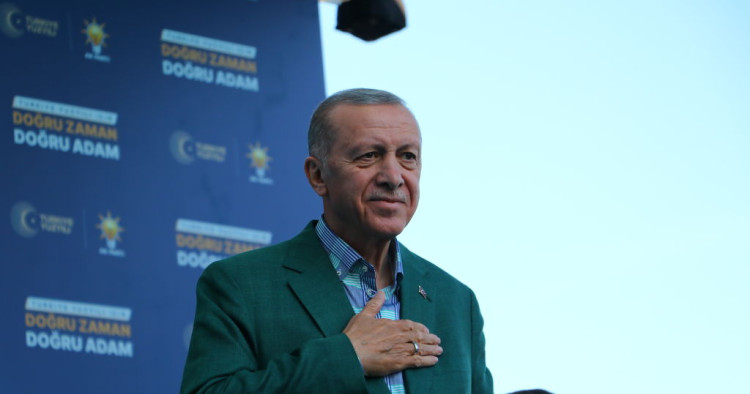

Turkey’s ruling AKP now faces the electoral scenario its opponents faced in 2002

W. Robert Pearson

Non-Resident Scholar

-

Twenty years ago, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) rode domestic turmoil and public anger to an overwhelming electoral victory, but today the incumbent government is a pale shadow of its promising beginnings.

-

Single-person rule and governing with the help of a media monopoly have neither saved Turkey nor promoted democracy, while scapegoating the West and dreaming of virtual empires have not made Turks wealthy; it remains to be seen if Turkish voters agree.

Two decades ago, a cumulative series of political, economic, systemic, and physical shocks led to the resounding defeat of an incumbent Turkish government and the coming to power of a new force on the political scene.

First, in August 1999, earthquakes killed more than 17,000 people and left homeless an estimated 500,000. The destruction of residential buildings caused most of the casualties. Public outrage erupted against private contractors and government officials due to shoddy construction and lax enforcement of building codes. A year and a half later, in February 2001, an open political break between Turkey’s president and prime minister produced a market panic: By August, a dollar bought 1,500,000 (old) lira (the Turkish currency losing more than half its value from before the crisis), jobs disappeared, income inequality reached new heights, and millions of middle-class Turks had lost their life savings. Corruption and the government’s inability to rule effectively further eroded public trust.

As a result of these developments, the government collapsed, leading to snap general elections, held in November 2002. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) rode this domestic turmoil and public anger to victory, winning 34% of the vote but gaining nearly two-thirds of the parliamentary seats. Clear and expert guidance, building on economic reforms introduced in 2001, then led to Turkey’s best economy in decades.

Flashing forward 20 years, however, the incumbent AKP government may now be a pale shadow of its promising beginnings. The February 2023 earthquakes in southeastern Turkey killed more than 50,000 people and injured and left homeless many thousands of others. More than 100,000 buildings and homes toppled to the ground. UNICEF reported Saturday that 2.4 million people are still in temporary settlements, including 1.2 million living mainly in containers and tents. An estimated 2.5 million children have been separated from their families, and many have lost their parents. Building codes again were found to have been widely ignored. Once again, there is widespread criticism of the government’s corruption.

Meanwhile, “opaque and erratic” economic governance and widespread concerns about the rule of law in Turkey have depressed foreign direct investment to historically low levels. Inflation in the economy is burning through savings and salaries. Turkey remains a middle-income country. Its ranking as the 19th largest economy in the world is even lower than it was 20 years ago. Unemployment has stayed high, especially for youth.

Years of single-person rule and governing with the help of a media monopoly have neither saved Turkey nor promoted democracy. Scapegoating the United States and the West and dreaming of virtual empires have not made Turks wealthy.

The Turkish people are long-suffering, but the AKP government will set everything right, we are told. Turkey is still a democracy, we are assured. Will Turks agree? This government may worry that 2002 is looming again — only this time, with the shoe on the other foot.

US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s quick weekend trip to the Middle East

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

-

Biden’s top national security aide traveled to the region, demonstrating once again that the administration is ignoring calls to pull back from the Middle East.

-

No major breakthroughs should be expected from this trip in the short run; the Biden administration is taking a long-term view when it comes to updating America’s engagement with the region.

“Every day, we are plugging away at proactive and creative diplomacy across the Middle East region,” U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said in a May 4 speech on the eve of his quick trip to meet the leaders of Saudi Arabia and Israel. His remarks were yet another sign that the Biden administration is staying engaged in the Middle East and sees it as a key region for advancing the United States’ interests and values.

To understand the trip Sullivan and his top Middle East team just made, last week’s speech offers a useful framework that notably lists five core principles guiding U.S. engagement: building partnerships, maintaining deterrence, leading with diplomacy, advancing regional integration, and keeping values as part of the agenda.

This framework was already previewed more than two months ago by Brett McGurk, the U.S. president’s top Middle East advisor. It builds upon the Biden National Security Strategy issued last year, and the basic approach reinforces a message President Biden sent to the region on his visit there last year: “The United States is invested in building a positive future in the region, in partnership with all of you, and the United States is not going anywhere.”

Sullivan’s visit this month itself sought to tackle the usual list of challenges and threats, including Iran’s nuclear program and ongoing actions destabilizing the region, the Yemen conflict, and tensions between Israelis and Palestinians. Given how complicated these issues are, it is not realistic to expect major breakthroughs on these immediate crises, but having Biden’s top national security aide consult with close partners reinforces the message that America remains the top security partner of choice of most of the leading countries of the region.

The most interesting feature of this particular visit was that Sullivan’s counterparts from India and the United Arab Emirates joined him in Jeddah to meet with Saudi Prime Minister and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for a discussion about regional integration. The officials reportedly discussed joint investments in infrastructure projects, including railroads and ports across the region. Though left largely unspoken during the meetings, the talks on transit infrastructure had clear geopolitical undertones. Both the U.S. and India hope to develop new east-west transit corridors linking South Asia, the Middle East, and Southeastern Europe that will rival China’s much-hyped Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) multi-modal projects. These ideas are linked to previous discussions about the I2U2 initiative, announced last year during Biden’s visit, a concept for joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, health, and food security involving Israel, India, the UAE, and the U.S. Israel wasn’t present at the meeting in Saudi Arabia, because the conditions aren’t ripe for open engagement between those two countries, and it seems unlikely to happen without signs of progress on the Palestinian front.

Like the long-term infrastructure projects for the region under discussion, current U.S. engagement in the Middle East is in the very early stages of trying to build something lasting that generates value and addresses pressing human security needs through partnerships and long-term investments. The Sullivan trip is the latest in a series of steps to help America shift its approach in the Middle East away from reactive crisis management while ignoring calls to abandon the region entirely, and instead it represents a move toward a steadier, more strategic re-engagement in the broader Middle East.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

Will Iran willingly share Syria?

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Black Sea Program

-

To those in Tehran who have long defended Iran’s controversial military intervention to save Assad, Damascus’ return to the Arab fold illustrates Iran’s inevitable rise as the dominant regional actor; but skeptics see rising costs for Tehran and a loss of Iranian influence.

-

It was, therefore, unsurprising that the core focus of Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s high-profile visit to Damascus last week centered on economic cooperation.

Iran is jubilant about Syria’s readmission into the Arab League. But implicit in the official Iranian narrative is that the survival and ongoing rehabilitation of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime is a secondary factor in Tehran’s rejoicing.

To those in Tehran who for the last 12 years have defended Iran’s controversial military intervention to save Assad from the Syrian opposition, Damascus’ return to the Arab fold illustrates Iran’s inevitable rise as the dominant regional actor. But there are also plenty of skeptics in Tehran who are not so sure. There are question marks about the costs Iran will have to continue to pay to keep Assad afloat; and it remains to be seen whether he will now move closer to the Arab world, if given the right incentives, at the expense of Iran’s clout in Syria.

According to Iran’s David-and-Goliath narrative, the Assad regime became the target of a plot by the United States and its Arab partners starting in 2011. The fact that plenty of Iranian officials at the time openly criticized Assad for his indiscriminate use of violence against the opposition is, today, conveniently omitted. History is written by the victors, and the architects of Iran’s regional interventions — from Syria to Iraq to Yemen — now claim to have been vindicated.

But Iran’s Syria intervention always had plenty of detractors, and they have not gone away. Doubts about the logic for Iran to stay deeply engaged in Syria will not dissipate just because Assad has been readmitted to the Arab League, an organization that reflects symbolic shifts in the region but lacks real power. To be able to call its Syrian intervention a success in the long-term, Tehran will need to make sure it is not sidelined as Syria enters the post-war reconstruction phase.

It was, therefore, unsurprising that the core focus of President Ebrahim Raisi’s high-profile visit to Damascus, on May 3-5, centered on economic cooperation. But can Iran and Syria engage economically at the bilateral level when both are essentially cash-starved? That is unlikely. At the same time, as part of the new trend of regional de-escalation, can Iran, for example, find ways to cooperate or coexist with Arab countries participating in the reconstruction of Syria; or would Tehran continue to see a greater role by yesterday’s rivals in Syria — the Gulf states in particular — as a net loss for Iran? The months and years ahead will reveal whether Tehran can thread that delicate needle.

Follow on Twitter: @AlexVatanka

UN meeting highlights ongoing frustrations and divisions over Afghanistan

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

-

The international community is forced to try to stabilize its relations with a country whose policies it abhors without sacrificing the wellbeing of the Afghan people.

-

A divergence exists between those countries like China that urge greater international engagement with the Taliban, and those like the U.S. that are resistant to closer contact and favor the idea of intra-Afghan political dialogue.

The international community continues to grapple with what to do about Afghanistan. Rather than the country fading from view with the end of open conflict in August 2021, its urgent humanitarian demands, draconian governance, and failure to contain the export of terrorism and narcotics have kept it high on the international agenda. Saddled with a Taliban regime largely resistant to external criticism, concerned countries and international organizations have been united in denying formal political recognition but have disagreed over how best to engage the Afghan government. In that light, last week the United Nations convened talks on Afghanistan in Qatar that were attended by representatives from about two dozen countries and organizations. Participants expressed worries about the stability of Afghanistan and, among other issues, showed particular concern with Taliban policies to bar women from employment with the U.N. and non-governmental organizations. Also in evidence at the meeting was the divergence between those countries like China that urge greater international engagement with the Taliban, and those like the U.S. that are resistant to closer contact and favor the idea of intra-Afghan political dialogue.

To no one’s surprise, the U.N. summit failed to produce a specific action plan. Still, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres defended the necessity of the exercise by arguing that it brought the various perspectives of the international community together so that the U.N. could find ways to talk to the Taliban with a unified front. The international diplomatic effort has angered, however, both the Taliban and Afghan women’s representatives, neither of whom were invited to participate in the meeting. The Taliban have dismissed the aired concerns, insisting that they have made progress domestically in the past 18 months in eliminating terrorism and drug trafficking and claiming to have created in Afghanistan a society free of corruption. On the defensive over women’s issues, the Taliban push back vigorously against foreign pressures termed as an intrusion into the country’s domestic affairs and lacking respect for its Islamic beliefs.

As much as Taliban leaders complain about being denied official international recognition, they have no fear of diplomatic isolation. Not only do several countries, including China, Russia, and Pakistan, maintain missions in Kabul, Taliban delegations are regularly invited to regional meetings that, in effect, confer on them de facto political recognition. Just last Friday, the acting foreign minister of the Islamic Emirate, Amir Khan Muttaqi, led a delegation to Pakistan to attend the fifth tripartite meeting between China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Moreover, the Kabul government has been allowed to station its diplomats in Beijing and Moscow.

In his recent Eid message, Taliban Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada declared his desire for cordial relations with the world. But he coupled this with a declaration of Afghanistan’s unwillingness to accept interference in its internal matters. The latest U.N. meeting on Afghanistan serves as a clear reminder that for all the international organization’s moral authority and the many areas of agreement on Afghanistan among members, its leverage against this aberrant Taliban regime is minimal. This leaves the international community forced to try to stabilize its relations with a country whose policies it abhors without sacrificing the wellbeing of the Afghan people.

Research assistant Naad-e-Ali Sulehria contributed to this piece.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Photo by Mesut Karaduman/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.