This essay is part of the Middle East-Asia Project (MAP) series on “'Civilianizing' the State in the Middle East and Asia Pacific Regions.” The series explores the past and ongoing processes of Security Sector Reform (SSR) in Asia-Pacific countries and examines the steps already taken and still needed in the MENA region. See More

It is widely accepted that South Korea has successfully consolidated democracy. For example, U.S. President Barack Obama cited South Korea as an exemplary case of economic growth and democracy in his famous speech at Cairo University on June 4, 2009. Two years later, when Egypt underwent a civil uprising that brought to an end the country’s decades-old Mubarak regime, he lauded South Korea’s democracy once again, suggesting that “Egypt could transform itself into a democracy on the model of Indonesia, Chile, or South Korea.”[1] By 2013, however, alleged election fraud in South Korea had damaged the international reputation of its mature democracy. The Democratic Party—the country’s main opposition party—publicly called the 2012 presidential election unfair because the National Intelligence Service (NIS) had manipulated public opinion prior to the election, leaving disparaging comments about opposition party candidate Moon Jae-in on popular websites.

After a series of investigations, Won Sei-hoon, the former NIS director, was prosecuted for violating the election law that prohibits civil servants from exerting influence on domestic politics by using their status. Democratic Party legislators took this opportunity to call for large-scale reform of the NIS to eradicate what has actually been a decades-old practice of interfering in elections. To answer the question of why NIS reform has not been successful under South Korea’s mature democracy, under both conservative and liberal leaders, this paper focuses on the origins and early history of the South Korean intelligence agency as a case study of security sector reform in South Korea.

Origins and History

The South Korean intelligence agency can be traced back to the military coup that General Park Chung-hee carried out on May 16, 1961. As the coup was brought about by a military faction consisting mostly of young reformist officers and not by the military as a whole, General Park had to strengthen surveillance over potential opponents within the military as well as civil society. This led him to establish the Capital Garrison Command (CGC) to suppress a counter-coup on June 1, 1961 and to create the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) on June 10, 1961 to integrate the intelligence activities of the army, navy, and air force under his direct command. In establishing the KCIA, General Park drew founders from the South Korean Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC), which was notorious for committing acts of terror and murder against political dissidents who were critical of President Syngman Rhee’s authoritarian regime in the 1950s.[2] Competing with the Defense Security Command (DSC)—a direct descendant of the CIC—for Park’s favor in the 1970s, the KCIA rarely supported the principle of political neutrality, instead engaging in torture, murder, and kidnapping of opposition leaders.[3]

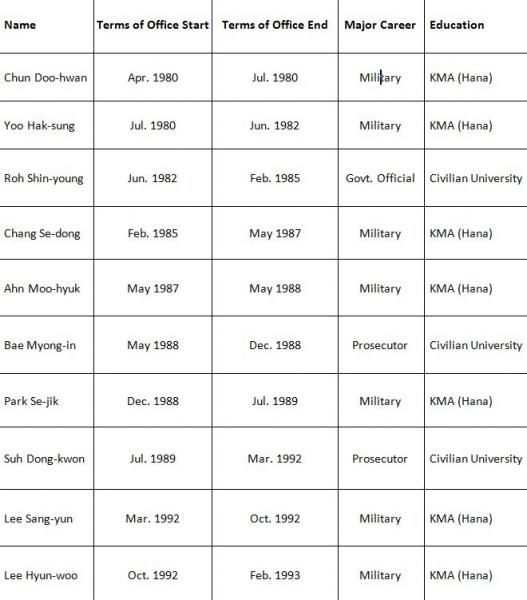

Table 1. List of the Agency for National Security Planning (ANSP) Directors (1980-1992)

Ironically, Park was assassinated on October 12, 1979 by a man he trusted highly, the former DSC commander and the incumbent KCIA director Kim Jae-kyu. After Park’s sudden death, the DSC commander General Chun Doo-hwan assumed power through a military coup on December 12, 1979. The successful coup allowed him to extend his control over the KCIA. With the help of these two oppressive apparatuses, General Chun was elected president through an indirect presidential election in August 1980. Making a career in the KCIA and the DSC simultaneously, Chun learned how to best use intelligence agencies to monitor and control political dissidents. In 1981, he transformed the KCIA into the Agency for National Security Planning (ANSP) and began a legacy of appointing allies to direct the Agency that his successor, President Roh Taw-woo, continued. As Table 1 demonstrates, the two presidents frequently assigned graduates of the Korea Military Academy (KMA) who were members of the Hana faction to head the Agency. These graduates were those with whom they had carried out the military coup in 1979. During the 1980s, parallel to the formation of this new military regime, the ANSP’s interference in domestic politics remained intact.

Civilian Rule and NIS Reform

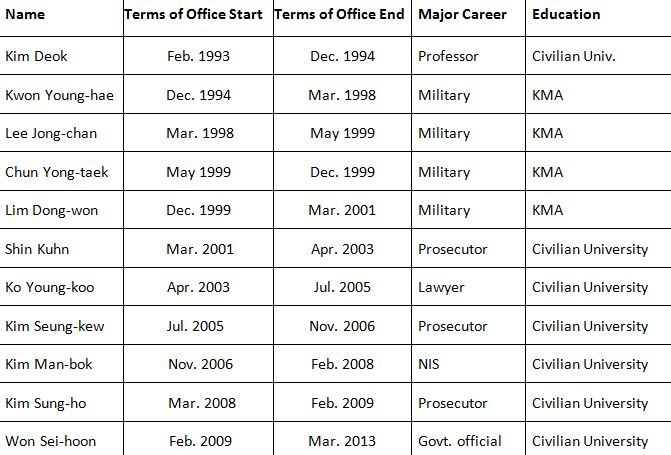

Inaugurated as the first civilian president since 1961, President Kim Young-sam took several measures to reform the ANSP in 1993, establishing an information committee in the National Assembly to effectively constrain the Agency’s illegal activities. He also appointed a prominent international politics professor, Kim Deok, as ANSP director. President Kim’s reform initiatives, however, proved to be unsuccessful. Even though the ANSP declared that it had banned warrantless wiretapping, a detailed report of its wiretapping activities was leaked to the press. Kim was not prosecuted but was blamed for tolerating these illegal activities under his watch. President Kim Dae-jung, who the ANSP attempted to keep out of power by means both fair and foul,[4] then implemented more extensive reform of the Agency. The former ANSP director Kwon Young-hae was prosecuted for conducting a massive disinformation operation to prevent Kim Dae-jung from defeating the ruling party candidate Lee Hoi-chang in the 1997 presidential election. Kwon was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison.

Changing the ANSP’s name to the NIS, President Kim requested that the NIS be a small but strong intelligence agency to serve the people rather than political power. Consequently, divisions for overseas intelligence activities were enlarged while those for internal security activities were trimmed. However, Kim was blamed for discharging a large number of agents who had been actively engaged in fighting North Korea’s agents in the south. President Kim’s successor, Roh Moo-hyun, embraced a similar attitude toward the NIS by supporting an engagement policy toward North Korea rather than one based on deterrence. As a result, President Roh was suspected of discharging the NIS director Kim Seung-kew to prevent him from investigating an espionage chain in which Roh’s protégés were involved.[5]

Table 2. List of ANSP (1993-1999) and NIS directors (1999-2013)

The liberal government’s reform initiatives have done more harm than good to the NIS for two reasons. First, they seriously damaged the morale and professionalism of the NIS. As individual success in the organization continued to be earned not on merit but on the president’s favor, NIS agents were motivated to appropriate illegally gathered intelligence to earn points with the incumbent president or the top-rated presidential candidate. Not surprisingly, political scandals regarding the NIS’s illegal interference in domestic politics continued. All NIS directors appointed by President Kim were investigated by the prosecutor’s office due to the disclosure of confidential information gathered through wiretappings, and two of them, Lim Dong-won and Shim Kuhn, were prosecuted and found guilty of illegal wiretapping activities. Although favored by President Roh Moo-hyun, NIS director Kim Man-bok also did not go quietly. He was prosecuted and found guilty of intentionally leaking his own private talks with a top North Korean official in which he praised the top-rated presidential candidate Lee Myung-bak with the purpose of earning political favor after the 2007 presidential election.[6]

Second, as the choice of NIS director has not been based on merit but on political allegiance to the president, the president-elect cannot choose high-ranking NIS officials appointed by the former president. It became inevitable that a large-scale reshuffling biased in favor of the incumbent president would follow the turnover of political power. President Lee Myung-bak first attempted to establish the principle of political neutrality in the NIS, appointing Kim Sung-ho, a prominent prosecutor, as the NIS director. Kim’s first task was to investigate political scandals that the NIS created to sway public opinion against Lee prior to the presidential election. However, Kim shared the fate of his predecessors, and was replaced with Won Sei-hoon, Lee’s confidant and closest associate, to strengthen Lee’s control over the organization. Won, who was a civil servant of the Seoul Metropolitan Government, lacked career experience and expertise in the intelligence field and thus could not distinguish between national security and regime security. Therefore the unprepared Won ordered NIS agents to leave thousands of comments against the opposition party’s presidential candidates on popular websites in the name of national security, causing serious damage to South Korea’s democracy.[7]

Conclusion

The South Korean case gives an important lesson to security sector reform for Middle Eastern countries for two reasons. First, South Korea’s civilian presidents never ignored the importance of security sector reform. However, their reforms did not pursue the establishment of political neutrality, but rather the removal of traces of their predecessors from the organization. In doing so, they triggered a cycle in which the incumbent president replaced high-ranking officials favored by the former president with his confidants in the name of reform. To use Samuel P. Huntington’s terminology, this approach of choosing the chief of the intelligence agency based on political loyalty is close to subjective civilian control. Such a move hampers professionalism in the organization and paves the way for its interference in domestic politics.[8]

Second, to some extent the failure of NIS reform can be attributed to outside—in this case North Korean—threats that have provided an advantage to South Korea’s conservative parties. As the NIS has changed its attitude toward North Korea over time, both conservative and liberal parties have alternately accused the NIS of exaggerating North Korean threats and neglecting its duty to combat such threats. It is worth noting that such a fragmented civil society, divided along fault lines based on political power, will make the security sector reform process more difficult. Therefore, security sector reform is feasible only through objective civilian control, which promotes mature professionalism consisting of expertise, social responsibility, and appropriate oversight.

[1] Hwang Doo-hyong, “Obama Hopes Egypt Will Follow S. Korea's Suit for Democratization,” Yonhap News, 3 March 2011, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/national/2011/03/04/91/0301000000AEN20110304000700315F.HTML.

[2] Gregory Henderson, Korea: The Politics of the Vortex (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), 350.

[3] Jinsok Jun, “South Korea: Consolidating Democratic Civilian Control,” Coercion and Governance: The Declining Political Role of the Military in Asia, Muthiah Alagappa, ed. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), 137.

[4] The KCIA kidnapped Kim and tried to kill him in Japan in 1973. He was also arrested by the founder of ANSP, Chun Doo-hwan, and was sentenced to death in 1980, although his sentence was commuted and he was given exile to the United States.

[5] “Ruling Party, Cheong Wa Dae Furious at NIS Chief,” The Chosun Il-bo, 31 October 2006, http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/10/31/2006103161009.html.

[6] “Prosecutors Launch Probe Into Leak by Spy Chief.” The Korea Times, 21 January 2008, http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2014/02/117_17656.html.

[7] “Ex-Spy Chief to Be Indicted for Political Meddling,” The Chosun Il-bo, 13 June 2013, http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2013/06/13/2013061301666.html.

[8] Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957), 80-84.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.