Israel has been experiencing rapid socio-political changes since Oct. 7, but one thing has remained constant: a widespread yearning for new leadership. For nearly six months now, public opinion polls have consistently indicated that a plurality of Israelis — across the political spectrum — have lost faith in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and support early elections, whether immediately or when the war winds down. Recently, this trend has been coupled with renewed demonstrations against the government and maneuvers by key politicians, indicating that the chances Israelis will go to the polls during 2024 are on the rise.

According to a public opinion survey published in February 2024 by the Israel Democracy Institute, 71% of Israelis believe elections should be brought forward from their original date in 2026, while a Channel 12 poll from March indicated that 50% of those identifying themselves as right-wing (and 40% of those who voted for Netanyahu’s political bloc) also wish for early elections.

This attitude is similarly gaining traction in Washington, DC. In early March, President Joe Biden stated that Netanyahu is hurting Israel more than helping it though his handling of the war in Gaza. Several days later, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer claimed that “a new election is the only way to allow for a healthy and open decision-making process about the future of Israel.”

The embattled Israeli prime minister vehemently dismisses such calls. In an interview with CNN, he said it is “ridiculous” to talk about early elections while the war is ongoing and claimed that Schumer’s comment was a totally inappropriate intervention in Israel’s internal affairs. As he struggles to ensure his political survival, Netanyahu has once again adopted a confrontational approach toward a critical yet friendly US administration.

For several months, public support for political change did not translate into tangible pressure on the government. Israelis were still in an early stage of processing the horrors of Oct. 7 and its consequences, including ongoing concern for the well-being of Israeli hostages held by Hamas, high-intensity fighting in Gaza, and escalation along the Israeli-Lebanese border. For many Israelis, the time did not feel right to protest.

Renewed protests

Yet by early 2024, a heightened sense of urgency emerged regarding the need for change. Doubts intensified among much of the population as to the wisdom of Netanyahu’s reluctance to present a plan for the “day after” the war; his capacity to achieve Israel’s war objectives, despite the prime minister’s repeated calls for a “total victory”; and his ability to manage foreign relations — first and foremost the alliance with the United States — with the necessary care.

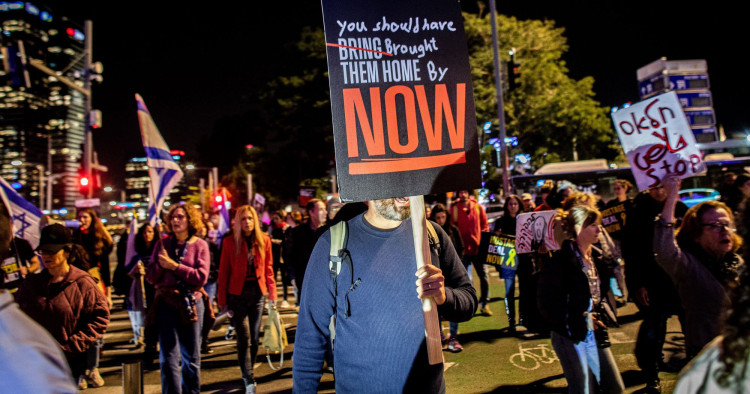

The renewal of public protests has been fueled by assessments that time is running out for the Israeli hostages, war efforts are stalling, those evacuated from northern and southern Israel remain unable to return home, and that Israel’s allies are turning against it. Increased police violence targeting peaceful demonstrators guided by far-right Minister of National Security Itamar Ben-Gvir has further intensified public anger.

This has not yet led to the eruption that many anticipated; but things may be heading in that direction. Last year, Netanyahu’s firing of Defense Minister Yoav Gallant led masses to storm the streets of Tel Aviv in the middle of the night, eventually forcing the head of government to reverse his decision. The trigger that could make such a night recur has yet to materialize but is widely expected to, sooner or later. In the meantime, street demonstrations continue to be organized by various groups, which are not always on the same page with each other, calling for issues such as bringing the Israeli hostages home, holding early elections, or requiring the ultra-Orthodox to perform military service.

Political maneuvering

In the immediate aftermath of Oct. 7, the major political parties tried to address the public need for unity and responsible leadership. The centrist National Unity party, led by former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Chief of Staff Benny Gantz, joined the coalition in a unity government, and an emergency war cabinet (excluding far-right parties) was set up. Opposition party Yesh Atid promised Netanyahu a safety net to ensure a parliamentary majority for any deal that would enable the release of hostages.

As time went by, however, political divisions resurfaced, for the same reasons that re-sparked public protests. The reluctance to engage in political maneuvering, even at a time of war, gradually fell away, supported by the fact that municipal elections were finally held in late February, after being postponed from October 2023 due to the war.

Minister Gantz made his move in March by visiting Washington despite the prime minister’s objection. The “unauthorized” high-level meetings he carried out there and the warm welcome he received from the Biden administration were a message to the Israeli public. They emphasized that there is an alternative to Netanyahu’s leadership, capable of carrying out effective diplomacy and putting US-Israeli relations back on track.

Around the same time, Defense Minister Gallant stated that he will not introduce the military draft bill exempting the ultra-Orthodox community unless all coalition parties agree to its language. By doing so, and against the will of Netanyahu and his ultra-Orthodox coalition partners, he effectively gave the National Unity party veto power, planting the seeds for a possible coalition crisis as a legal deadline on this matter, issued by Israel’s Supreme Court, looms.

A couple of weeks later, Minister Gideon Sa’ar and his right-wing faction split from the National Unity party. This is a possible step toward establishing a new party — which other right-wing politicians may also aspire to lead — that will challenge Netanyahu and profit from the rise in hawkish public attitudes after Oct. 7. Sa’ar has also demanded a place in the war cabinet, which was not only opposed by Gantz but has also spurred the other far-right coalition partners to ask for the same, thus intensifying intra-coalition tensions. After his demand was rejected, Sa’ar’s faction quit the coalition.

In parallel, the opposition has begun preparing for early elections as well as deliberating on post-Oct. 7 diplomatic plans. Yair Lapid won the first-ever Yesh Atid leadership primaries. The Labor party will elect a new leader in May, probably enabling consequent mergers and renewal within the Israeli left, which currently suffers its lowest-ever representation in the Knesset. Former general and Oct. 7 hero Yair Golan is on course to win these primaries, vowing to launch a new political framework afterward.

What might happen next

The factors that could spark early elections in Israel are multiplying and growing stronger: sustained and broad public support for new leadership, increased pro-change pressure coming from the streets, preparations and positioning by key political actors toward an upcoming campaign, and messages from top American officials that change in Israel is needed.

Despite these accumulating indications, it is still unclear at what pace political events will unfold and according to which scenario; at the same time, Netanyahu’s skills at political survival should not be underestimated. In previous times of potential political crisis, Netanyahu repeatedly showcased his ability to take control of political events. For example, he called for snap elections when it best suited him, rather than waiting for opponents to act and topple the coalition. There is speculation within Netanyahu’s circles that he may do so again.

After Oct. 7, however, such tactics may no longer work in his favor. Instead, a domino effect could take place, in which a decision by one party to leave the coalition — not necessarily a large party or due to war-related differences — will lead to a quick downfall of the coalition. Such a scenario has happened in the past and should be kept in mind as the Knesset prepares to go on recess starting April 7. Differences around ultra-Orthodox military service legislation are already sparking speculation about back-channel deals regarding early elections.

In any case, an election process in Israel takes time. After a dissolution of the Knesset, it takes around 100 days before Israelis go to the polls. Moreover, elections almost never happen during July (last time this happened was in 1984) or August (last time in 1961), nor are they held during the Jewish holiday season (this year in October). Finally, even once elections are held, it can take an additional couple of months until a coalition is formed.

If Israel continues to follow this political timeline, clarity about its next leader may not emerge before late 2024. This has implications for the Biden administration’s policy toward developing plans for a “day after” reality for Gaza and the region. Netanyahu is not a willing partner for the type of plan the US has in mind, which involves steps toward an Israeli-Palestinian two-state solution. He might even become an actor in domestic American politics, given his strong ties to the Republican Party.

Yet should early elections in Israel be called well before Americans go to the polls in early November, it will give the Biden administration some time to present Israelis with the benefits they could reap from having a more moderate and pro-peace coalition in place. Normalization with Saudi Arabia, empowerment of Palestinian moderates, enhanced cooperation with the US, and improved global standing could all be introduced during an Israeli election season as major incentives for change.

Dr. Nimrod Goren is the Senior Fellow for Israeli Affairs at the Middle East Institute, President of Mitvim - The Israeli Institute for Regional Foreign Policies, and Co-Founder of Diplomeds - The Council for Mediterranean Diplomacy.

Photo by Eyal Warshavsky/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.