Introduction

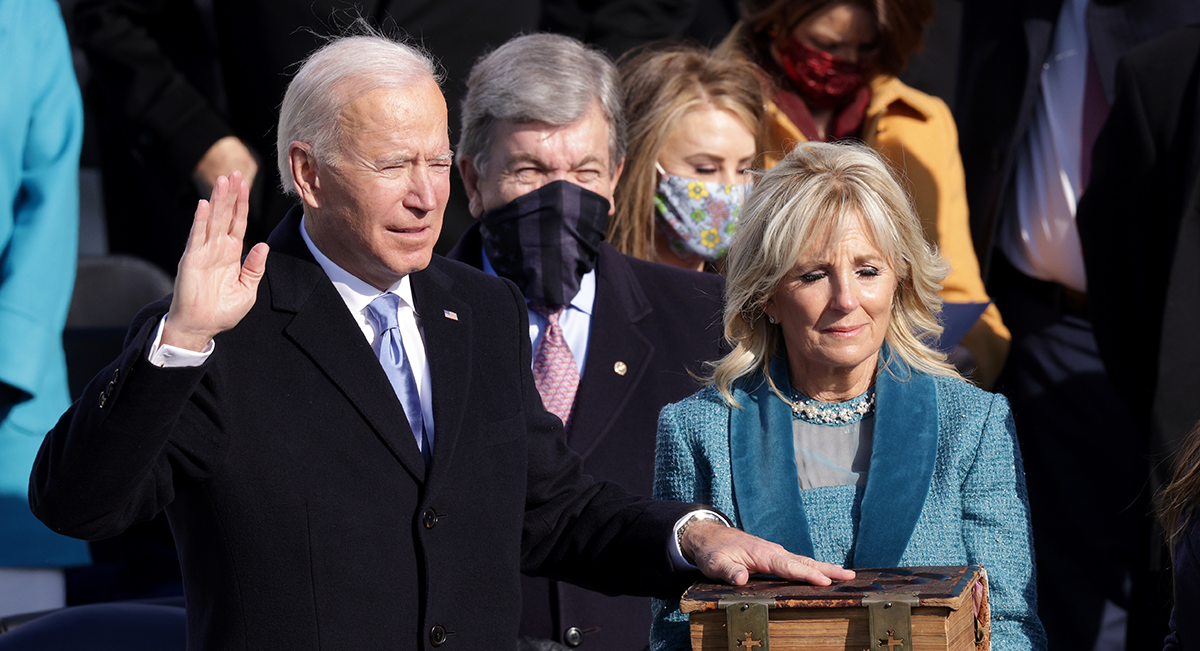

As the Biden administration takes office on Jan. 20, it faces a host of challenges, both at home and abroad. Where does the Middle East fit into all of this and what can the new administration achieve in the region in its first 200 days? In the first part of a two-part series, we asked 9 experts and scholars from across Washington to weigh in with their thoughts.

Read part two: Regional perspectives

This publication is part of MEI's series on the Biden Transition.

Viewpoints

-

Wa'el Alzayat

Wa'el Alzayat

Four things President Biden can do that will make a real difference in the Middle East

The Biden administration should immediately restore funding to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA). Donald Trump had cut off $300 million of funding that went toward educating nearly half a million children, vaccinations and health clinics for 3 million refugees, and other essential support. These funds are tangible actions that save lives and signal a departure from Trump’s mean-spirited policies.

Joe Biden should also unfreeze the $200 million in Syria stabilization funding that Trump put on ice right after declaring that the U.S. would be leaving Syria “very soon” and letting “other people take care of it.” Of course that decision was reversed, but the funds’ suspension was not. While the original funding was for the northeast, support is also needed for Idlib, where 3 million people are huddled in extreme weather conditions, with some sleeping out in the open. Even as a political settlement remains elusive, much can be done to alleviate the situation there.

The new administration should review and do away with Trump’s so-called extreme vetting of refugees. Even after the “Muslim ban” has been rescinded, many Trump-era obstacles will need to be undone to enable refugees to actually travel, especially those who are Muslim. These include the expansion of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ Controlled Application Resolution and Review (CARRP) program, inefficient social media screening that relies on inaccurate free Arabic translation services, and expansion of Security Advisory Opinion (SAO) checks, which disproportionately target Muslims. These policies harm those most vulnerable without making us any safer.

This last recommendation is unlikely to be completed within the first 200 days, but it should be launched within that time frame. Given its impact on Middle East priorities, Biden’s national security team should prioritize resetting the relationship with Turkey. While the list of contentious issues appears to only be increasing, there is practical and strategic merit in getting the relationship back on track, or at least initiating a quiet process to begin unpacking key areas of disagreement. From Iraq to Syria to Libya, Turkey can be a critical facilitator of U.S. interests, or a serious obstructionist.

Wa'el Alzayat is CEO of Emgage, a national civic engagement organization for Muslim Americans. He is also a non-resident scholar at MEI and was senior policy advisor to U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power.

-

Sarah Yerkes

Sarah Yerkes

Put democracy and civil society first

Within the first 200 days of taking office, the Biden administration should carry out its promise to hold a Global Summit for Democracy. This would serve two overlapping goals: beginning to repair democracy at home and telegraphing the new administration’s commitment to democracy abroad. In the wake of the Jan. 6 failed insurrection at the U.S. Capitol and the ongoing threat from homegrown violent extremists against American democracy, it is crucial that Joe Biden and his team undertake a serious analysis of the damage inflicted on U.S. institutions over the past four years. The summit would offer the United States a chance to listen to other countries facing similar challenges, rather than preach about American exceptionalism.

Most MENA countries would be left out of such a summit, but that does not preclude opportunities to engage with the region on democracy and governance as part of the summit and its follow-on activities. First, the summit would coincide with the 10th anniversary of the Arab Spring, and therefore would be a good platform for the Biden administration to reinforce the idea that the Arab people have a voice and to celebrate the successes of the activists who poured into the streets in 2010-11 and continue to do so a decade later. The summit should also devote special attention to the success of Tunisia’s democratic transition, which, despite its challenges, continues to serve as a beacon of hope for many in the Arab world.

The Biden administration should, as my colleagues Frances Brown, Tom Carothers, and Alex Pascal have argued, carefully consider the invitation list to the summit, basing admittance on well-thought-out criteria and using invitations as a way to reward countries that are clear and consistent in their commitment to making progress in governance, human rights, and social justice. Countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt that so blatantly violate the rights of their citizens cannot be allowed to buy their way into the summit and their false promises about their desire to reform cannot be used as currency.

Finally, the summit offers an opportunity for the Biden administration to reestablish relationships with civil society actors around the world, including the many incredibly brave MENA activists whose work has only become more dangerous and difficult over the past four years. While Donald Trump largely ignored non-governmental actors, Biden should make clear, through engagement via the summit and beyond, that civil society has a seat at the table and the voices of the people will not be ignored.

Sarah Yerkes is a senior fellow in Carnegie’s Middle East Program.

-

Michael Eisenstadt

Michael Eisenstadt

The security agenda

The Biden administration’s national security team may be tempted to focus on potential early tests by foreign adversaries, urgent matters demanding immediate attention, and potential “quick wins”: strengthen and lengthen the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran; build on and expand the Abraham Accords; consolidate the Gulf Cooperation Council reconciliation process. Certainly, it should do all these things. But in its first 200 days, it also needs to fundamentally rethink how the United States can advance its interests in a conflict-prone region located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, as it increasingly turns its attention to the Indo-Pacific region and other parts of the world.

The Middle East’s most vexing problems cannot be “solved” — at least for now; crises will need to be “managed.” Seeking to freeze conflicts or play the role of spoiler may lack appeal to U.S. policymakers used to playing the role of regional peacemaker or hegemon, but these alternative policy approaches can halt humanitarian disasters and deny victory to adversaries. In many cases, that will be good enough. And the United States must become more adept at the limited use of force in circumstances well short of war; that will, unfortunately, remain necessary in the Middle East. Policymakers need a vocabulary and mental models more appropriate to “by, with, and through” and gray zone operations, in order to advance U.S. interests with a light force footprint, in ways that bolster diplomacy but do not roil a war-weary public back home. They likewise need to rethink how the United States trains foreign militaries, in order to build partner forces capable of bearing their share of the defense burden. And the United States needs to launch a missile defense Manhattan Project to develop the means to defeat the main asymmetric capability possessed by U.S. adversaries in the Middle East and elsewhere.

The roots of many of the region’s conflicts are structural and cultural: large youth bulges; rapid urbanization; extreme gender hierarchies; destructive governance models; conflict-prone honor cultures and super-charged asabiyas (social solidarities). All of these are risk factors for instability, violence, and state failure that interact in often subtle and harmful ways, and that are exacerbated by stressors such as climate change and environmental degradation. Addressing these looming challenges will require long-term approaches that transcend the traditional policy toolkit. The Abraham Accords, however, may offer a first step toward the kind of regional and global partnerships necessary to better manage the Middle East’s present conflicts and address its future water and food security, public health, and climate challenges. Let’s get to work!

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Fellow and director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy's Military and Security Studies Program.

-

Elizabeth Dent

Elizabeth Dent

A diplomacy first approach

While the majority of the Biden-Harris administration’s initial efforts will focus on current domestic issues plaguing the United States, we can also expect the new team to roll out a number of initiatives related to foreign policy. Notably, throughout his campaign, President Joe Biden has articulated a desire to breathe new life into U.S. diplomacy and end President Donald Trump’s practice of cozying up to dictators around the world.

In the Middle East context, the first 200 days of the new administration should focus on restaffing embassies abroad and ensuring proper leadership with experienced ambassadors at the helm in critical posts who can emphasize the importance of diplomacy to foreign partners and re-establish U.S. credibility. One of the Trump administration’s biggest problems was that only Trump spoke for himself, so his representatives often found themselves in direct contradiction to his public messaging, leaving space for foreign counterparts to capitalize on perceived weak spots in U.S. policy. The Biden team would do well to ensure key representatives are in place quickly and employ strict message discipline with foreign interlocutors. Immediate messaging will likely also need to focus on elevating concerns about human rights and political prisoners to more authoritarian governments.

Substantively, the new administration has already promised to rescind the “Muslim ban” on day one — a move which will help counter perceptions of U.S. Islamophobia in the region. President Biden has promised to increase refugee visas, but he should also support Special Immigrant Visas for Iraqis and Syrians who aided U.S. efforts to fight ISIS.

Assuming Iranian compliance, we can expect the Biden-Harris team to roll out an immediate initiative to renew diplomacy with Iran and reenter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Some of the initiatives already planned, including rescinding the “Muslim ban,” as well as messaging President Biden made as a candidate, can act as initial good faith measures to signal U.S. willingness to return to the negotiating table with Iran.

We can also expect the new administration to restore U.S. leadership in humanitarian assistance and press allies to offer more, too. In the immediate term, this should mean re-evaluating and increasing humanitarian assistance in critical areas like Yemen and Syria, resuming aid to the Palestinians, and providing COVID-19 assistance to countries in the region that request it.

The first 200 days of the Biden-Harris administration should act as a full reset of relations with most of the countries in the Middle East. From Iraq, where President Trump signaled the U.S. was only there for the oil; to Egypt, now one of the worst countries in the world for political and press freedom; to Syria, which will require a reinvigoration of diplomacy to bring about a political solution to end the civil war; President Biden and his team have their work cut out for them to reverse the damage the last four years have wrought.

Elizabeth Dent is a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Countering Terrorism and Extremism Program. She previously served as the special assistant to the special presidential envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS.

-

Gerald Feierstein

Gerald Feierstein

Biden’s successful Gulf strategy depends on Saudi Arabia

On the campaign trail, President Joe Biden emphasized his determination to reverse core elements of the Trump administration approach to the Gulf region in the opening days of his administration. He was critical of Donald Trump’s decision to walk away from the Iran nuclear deal and to pursue a “maximum pressure” campaign against the Iranian regime in the belief that it would force Tehran back to the negotiating table to conclude a more favorable deal for U.S. interests. He supported congressional resolutions aimed at forcing Trump to end U.S. support for the Saudi military campaign in Yemen, cut off arms sales to the Saudis, and hold the Saudi government accountable for the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the violation of human rights and civil liberties in Saudi Arabia. Finally, he made clear that he would pursue a more aggressive campaign to end the conflict in Yemen and relieve the humanitarian suffering in that country.

In several of these initiative, particularly on Saudi Arabia and Yemen, the incoming Biden administration is likely to find strong, bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. Indeed, he may find that members of Congress are pressing him to move more quickly and more aggressively to implement his promised changes. Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), for example, has already pledged to reintroduce the War Powers Resolution aimed at forcing a cut-off of military assistance to Saudi Arabia and the UAE that President Trump vetoed in 2020. Several other members also plan to introduce legislation to block recently approved arms sales to the two Gulf Cooperation Council partners.

The new administration may quickly find, however, that several of these initiatives are in conflict with one another. In particular, progress on the Yemen file, which the incoming team would like to hold out as a “quick win” for their policy initiatives, will be difficult to achieve in the absence of a cooperative push between Washington and Riyadh. Similarly, strains in the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship will complicate efforts to move forward on a revised approach to Iran. Thus, despite frustration with a number of Saudi domestic and foreign policy positions, the Biden administration will be under pressure in its first months to establish a nuanced approach to relations with Riyadh that allows for cooperation despite differences.

Amb. (ret.) Gerald Feierstein is senior vice president at MEI. He previously served as the U.S. ambassador to Yemen and principal deputy assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs.

-

Karen E. Young

Karen E. Young

First, focus on facilitating financial support

The big goals are to re-enter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, re-engage Saudi Arabia and Gulf allies in a regional security dialogue, and at the same time, re-set the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship, drawing clear red lines on targeting U.S. citizens or residents abroad and dissidents on U.S. soil. A strategic review of the U.S.-Saudi relationship is in order, but this should be conducted out of the spotlight and released toward the end of 2021. A congressional debate and administration policy decision on arms sales to the Gulf states should come after a first order decision to re-enter the JCPOA. These goals are possible, but they won't happen easily or quickly.

But there are also some simple policy choices that can move toward equally important regional stability goals. A basic way to start is in facilitating finance, in the form of grants, aid or multilateral loans, to states in the region to ease fiscal limits of the pandemic public health burden and provide support to communities most at risk. There can be strings attached, or conditionality, to all of these financial support measures. These can all be immediate actions in early 2021.

1. Facilitate immediate financial support for Iraq's electricity needs and public sector wage bill. Commit to an infrastructure support plan to build new power utilities or support GCC efforts to transmit electricity to Iraq.

2. Facilitate the IMF release of a $5 billion package to Iran, with strings attached for public health needs and accountability within the Central Bank of Iran for counter-inflation policy and support directly to SMEs. This will ease the return to the JCPOA, perhaps give political cover to reformist elements in advance of Iranian presidential elections, and create an incentive to begin discussions on issues beyond the JCPOA without immediate sanctions relief.

3. Make refugee support a central policy priority, working to rebuild America's position as a multilateral partner and source of financial and logistical support. Coordinate and supplement UNHCR COVID-19 support, particularly in the form of cash transfer programs to refugee communities in Iraqi Kurdistan, Lebanon, and Jordan.

4. Reverse or at least review the Houthi terrorist designation. Facilitate COVID relief and protection for humanitarian aid flows, including security protection to Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen. Move toward a U.S.-facilitated peace process, in line with the efforts of the U.N. envoy.

Karen E. Young is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

-

Robert S. Ford

Robert S. Ford

Secure humanitarian aid deliveries

The two worst humanitarian crises in the world are in the Middle East and the Biden administration can better address them with steps that would facilitate humanitarian aid deliveries in Yemen and Syria.

Yemen

- Instruct and staff the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) at the Treasury to issue licenses quickly for humanitarian aid organizations operating in Yemen that are at risk of being unable to conduct financial transactions due to the Trump administration’s designation of Ansar Allah (the Houthi movement) as a foreign terrorist organization. Aid organizations urgently warn that without licenses that allow for aid deliveries in territories controlled by the Houthis, millions of at-risk Yemenis could see aid deliveries disrupted or shut off.

- Begin a longer-term assessment of whether the secretary of state should revoke the Ansar Allah listing for foreign policy reasons, as allowed by the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Syria

- Consult promptly with European humanitarian aid officials, humanitarian organizations, and the U.N. Office for the Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs to identify specific measures the Syrian government employs to impede or profit from U.N.-managed humanitarian aid deliveries inside government-controlled territories. Develop with the Europeans an agreed list of steps the Syrian government must take to justify continued Western funding of the U.N. humanitarian operation in those territories.

- Consult with the U.N., humanitarian organizations, and the Russian government about humanitarian aid issues in Syria before the July 2021 U.N. Security Council renewal of the U.N. mandate for cross-border aid deliveries into northwestern Syria. Through its veto power at the renewal votes over the past two years Russia has reduced the number of cross-border aid delivery points from four to just one, and it insists that Damascus should assume country-wide oversight of humanitarian aid operations. The Syrian government will restrict or block aid to the opposition-controlled northwestern part of Syria with its 3 million civilians, who justifiably fear return of government control. Especially after Bashar al-Assad’s reelection this spring, Russia may seek to shut down the final cross-border aid operation, and so the new administration also should begin planning in consultation with the U.N., Turkey, and European aid donors for a fallback plan to ensure continued aid deliveries into northwestern Syria.

- The Department of Homeland Security should also renew Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Syrian citizens in the United States, which expires in March 2021. TPS for Syrians began in 2012 and affords protection to approximately 7,000 Syrian citizens in the U.S., many of whom would face arrest upon their return to Syria.

Region-wide

Ensure that the Treasury and the Government Accountability Office begin reassessing the broad problem of banks’ reluctance to work with humanitarian aid organizations in areas where sanctioned foreign entities also operate, as required in the National Defense Authorization Act. Banks’ reluctance (de-risking) has impeded international humanitarian aid operations in Yemen and Syria (and Iran).

Amb. (ret.) Robert S. Ford is a senior fellow at MEI. He previously served as the U.S. ambassador to Syria and deputy U.S. ambassador to Iraq.

-

Dania Thafer

Dania Thafer

Use regional partners as force multipliers to seize opportunities for dialogue in the Gulf

There has been an overarching trend toward regionalized security and an appetite for increased dialogue in the Persian Gulf. President Joe Biden should achieve U.S. foreign policy goals by seizing shifting opportunities to facilitate dialogue and diffuse regional tensions.

In reference to renegotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Biden administration should take advantage of regional states that maintain amicable relations with Iran to facilitate negotiations. Oman and Qatar are amenable to playing such a role. There has been an insistence from U.S. regional partners to be kept abreast of developments over a possible Iran deal. Addressing the concerns of regional partners should certainly be on the table, but it will also increase the obstacles to reaching a consensus. Therefore, if in the likely case that an agreement is realized for the JCPOA that falls short of fully appeasing regional partners, both the Americans and Europeans should use their political leverage to facilitate dialogue on regional security issues between Iran and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

The shift from Donald Trump to Biden itself tips the balance toward dialogue between Iran and the GCC states. Moreover, the aftermath of the 2017 Gulf crisis, which caused Qatar to lean toward Iran, arguably has a silver lining. It brought about an aggregate effect on relations between the GCC and Iran by tipping the balance more favorably toward opportunities for dialogue between the two sides.

The Biden administration has stated that it will end U.S. support for the Yemen war. The priority should first and foremost be the reversal of the designation of the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization because it complicates the United Nation’s efforts to broker a resolution to the war and risks worsening the already dire humanitarian crisis. The reversal of the designation does not mean the Houthis are innocent, but the cost of such a move outweighs its benefits.

Even if the U.S. manages to stop Saudi Arabia’s campaign in Yemen, there will still need to be more efforts devoted to arriving at a comprehensive solution to the conflict. The U.S. should put its weight behind further dialogue and incorporate neutral regional parties that can be a force multiplier for de-escalation, dialogue, and trust-building. Kuwait and Oman are two countries that can offer support with mediation. In addition to the most recent efforts, Kuwait has experience in mediating past Yemeni conflicts in 1972 and 1979. The late Kuwaiti emir played a more public role in mediation efforts through hosting talks and shuttle diplomacy, while Omani efforts have emphasized backchannel mediation. Kuwait is a slightly more neutral arbiter than Oman for the simple fact it does not share a border with Yemen, which allows for more flexibility in mediation. Nonetheless, the U.S. would only benefit from taking advantage of both Kuwait’s overt and Oman’s covert approaches to mediation, which can offer dual pressure points for dealing with the conflict.

The al-Ula summit agreement was a confidence-building measure that offers the GCC states a framework for moving toward further regional reconciliation. However, resolving the Gulf crisis will still require considerable diplomatic heavy lifting and it remains a substantial bottleneck for regional conflicts. The U.S. should exercise its influence in promoting bilateral talks between Qatar and “the quartet.” A full reconciliation could go a long way toward helping to diffuse tensions in other regional crises, such as in Yemen, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, and the Horn of Africa.

Dania Thafer is the executive director at Gulf International Forum and professorial lecturer at Georgetown University.

-

Jeffrey Feltman

Jeffrey Feltman

To avert chaos in the Horn of Africa, Biden should engage the Gulf and Turkey

Wars in Syria, Yemen, and Libya demonstrate that unresolved conflicts generate transnational terrorism, provoke humanitarian catastrophes, propel migrations that disrupt politics far from the battlefield, and become theatres for proxy clashes. Given these lessons, the Biden administration should prioritize conflict prevention, starting with the Horn of Africa. With Ethiopia’s population alone exceeding 110 million, conflict in the Horn could make Syria look like child’s play. Some of the most influential players in the Horn are across the Red Sea. The Biden administration needs urgently to transcend the bureaucratic divisions between “Africa” and “Near East” and engage Gulf countries and Turkey to stabilize the Horn of Africa before it is too late.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s military assault in the Tigray region opened a Pandora’s box, including over 50,000 Tigrayan refugees fleeing to Sudan and Eritrean refugees forcibly repatriated to uncertain fates in Eritrea. Ethiopia’s Oromo region is restive, and shocking ethnic massacres are reported in Ethiopia roughly every two weeks. Ethiopia and Sudan are clashing over disputed farming areas. Somalia’s president shares Abiy Ahmed’s desire to dial back federalism, pitting both against provincial leaders. Elections scheduled in both countries in 2021 are likely to provoke violence. Sudan’s transition remains fragile. Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia quarrel over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Any one of these issues could explode into crisis with dire strategic implications.

U.S. government officials will instinctively turn toward Africa to help avert a meltdown in the Horn. The African Union (AU) and the Inter-governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Horn’s sub-regional organization, are our traditional go-to partners. But the influence of IGAD erodes as Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia come closer at the expense of the larger collective. Ethiopia has brushed aside AU mediation efforts.

U.S. coordination with African partners is important but insufficient. Washington must look east as well. The UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey all exercise extensive influence in the Horn. The UAE has cultivated close relations with the leaders of Ethiopia and Sudan, in addition to long-standing ties with Asmara and Cairo. It is likely that Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed can reach all Horn leaders more readily than African leaders can, and Khartoum has reportedly encouraged UAE mediation of its disputes with Ethiopia. The UAE-Turkey regional rivalry plays out dangerously in Somalia.

Promoting stability in the Horn requires the Biden administration to add and even prioritize African issues on our bilateral agendas with our Gulf partners, Egypt, and Turkey. Persuading our Arab and Turkish partners to stop eyeing each other and instead promote stability in the Horn should not be an impossible sell: Chaos in the Horn and its impact on Red Sea trade and migration flows affect their interests even more directly than ours. But it demands U.S. focus.

Jeffrey Feltman is the John C. Whitehead Visiting Fellow in International Diplomacy at the Brookings Institution. He previously served as the under-secretary-general for political affairs at the U.N. and the U.S. assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs.