Summary

Since the launch of Vision 2030 six years ago, Saudi Arabia has made considerable progress in reducing the labor-cost gap between national and foreign workers in the private sector. While the total unemployment rate has declined recently among nationals, it remains high at 11%. Drawing on evidence from Bahrain’s experience with labor market reform, this can be significantly reduced through policies designed to bridge the cost gap between citizens and foreign labor in the private sector.

Contents

I. Introduction

II. Proposed Labor Market Reforms

Why the Bahrain Case Matters and its Relevance to Saudi Arabia

Addressing Domestic Unemployment by Equalizing Worker Mobility

B. Minimum Wage for All Workers in the Private

Sector

Can Some Firms be Exempt from Minimum

Wage Regulations?

C. Equalizing GOSI Contributions

III. Conclusion

Policy Recommendations

References

Executive Summary

Since the launch of Vision 2030 six years ago, Saudi Arabia has made considerable progress in reducing the labor-cost gap between national and foreign workers in the private sector.1 As a result, a recent report by the World Bank has shown that Saudi Arabia’s labor market is becoming more competitive with rising worker mobility.2 In addition, women’s participation in the workforce has more doubled since 2016, reaching a historical high of 35.6% in Q4, 2021.3

While the total unemployment rate has declined recently among nationals, it remains high at 11%, well above the Vision 2030 target of 7%. The unemployment rate for Saudi women remains even higher at 22.5%.4 In this paper, I argue that the unemployment rate for Saudis can be reduced significantly through policies designed to bridge the cost gap between citizens and foreign labor in the private sector.5

Drawing evidence from Bahrain’s experience with this labor market challenge, I propose three labor market policies to gradually close the cost differential. This would increase the competitiveness of Saudi workers in the private sector by helping to address a major reason why private firms currently prefer foreign labor and encourage merit-based hiring.

Key Policy Recommendations

- Equalize labor mobility for all workers regardless of their nationality.

- Introduce a private sector universal minimum wage for all employees irrespective of their nationality.

- Match social security contributions paid by employers for nationals and foreign workers alike.

I. Introduction

Even with recent employment contract reforms, private firms in Saudi Arabia still prefer foreign workers over nationals in part because the former are less mobile. Regulatory restrictions increase the likelihood of foreigners remaining with their employers for at least 12 months.6 Using Bahrain as a case study, I argue that granting foreign workers the right to quit at any time would make them less attractive in the eyes of employers, thereby increasing the employability of Saudi workers in the private sector. Based on my calculations, during Bahrain’s experiment with full labor mobility, the wage gap was reduced to a mere 9.3%, compared to 22.5% in the two years preceding the labor reform.7

Imposing a universal private sector minimum wage for all workers, no matter their nationality, would also reduce the wage gap, incentivizing private firms to hire more Saudis. Sectors that mainly rely on low-skilled foreign labor, such as construction and manufacturing, could be exempted from this mandate.

Private employers also prefer non-citizens over Saudis, even when their qualifications and educational attainment are similar, because employers can pay less for foreign workers under General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI) regulations. Specifically, in the case of foreign workers, companies only pay 2% for occupational hazards. By comparison, a private firm that hires a Saudi worker needs to pay not only the 2% for occupational hazards but also 9% into the GOSI pension system and 0.75% into SANED, the national unemployment insurance system.8 To make Saudis more competitive in the market, the GOSI contributions paid by private companies should be equalized regardless of a worker’s nationality. This change would bring Saudi Arabia into line with the policies of most other labor markets around the world.9

II. Proposed Labor Market Reforms

The following sub-sections will explain in detail the rationale behind each of these three policy recommendations

A. Equalizing Labor Mobility

Equalizing labor market mobility for all workers will reduce the yawning wage gap between citizens and expats.10 Such a reform will make citizens more employable in the private sector, as workers will be hired based on merit, rather than the differing labor protections granted to each group. Empirical evidence from Bahrain, which introduced several labor market reforms in 2008 and 2009, supports this contention.11 Bahrain’s experiment with labor market reforms provides an instructive example for Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, and they would benefit from adopting similar measures.

To combat unemployment among nationals and to attract skilled foreign workers, Saudi Arabia passed several policies in March 2021 that provide foreign workers more flexibility in the workforce and limit the power of private employers. For example, they can now travel outside the country without the permission of their companies.12 In addition, foreign workers can now leave employers who fall at least three months behind on paying their wages.13 A recent IMF paper praised these reforms, arguing that they will make Saudi Arabia’s labor market more competitive and more attractive to talented foreign workers.14 While these reforms are certainly a step in the right direction, numerous adjustments are still needed to equalize labor mobility and reduce unemployment among citizens.

Despite recent reforms, private firms continue giving preference to foreign workers for two major reasons.15 First, foreign workers must still spend 12 months with their initial sponsor before they can switch to another private firm. Second, although expat employees can now apply to leave the country before their contract ends, once they travel abroad, they cannot reenter Saudi Arabia during the vacation period granted to them by their employer.16 This may discourage foreign workers from leaving their employer before their contract ends.

Why the Bahrain Case Matters and its Relevance to Saudi Arabia

As mentioned in the introduction, Bahrain’s experience with eliminating certain labor restrictions on foreign workers between 2009 and 2011 offers an example of the economic benefits such reforms can create for citizens and foreigners alike. While Saudi Arabia’s private sector dwarfs Bahrain’s, the two labor markets share a similar composition. In both countries, a large wage gap persists between nationals and foreigners,17 which leads to a strong preference among private firms for low-skilled foreign labor.18

The table below highlights similarities in the labor market structure of Saudi Arabia’s and Bahrain’s private sectors. Three communalities stand out:

- Private sectors with jobs held primarily by non-citizens

- A high share of foreign labor holds only a high school degree or less

- High average wages for nationals relative to foreign workers.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Saudi vs. Bahraini private sectors

|

Country |

Saudi Arabia |

Bahrain |

|

% of foreign labor |

76.3%19 |

81%20 |

|

% of low-skill foreign labor |

65.9%21 |

75%22 |

|

Wage rate differential23 |

2.53 |

2.28 |

Addressing Domestic Unemployment by Equalizing Worker Mobility

By 2007, Bahrain’s unemployment rate among citizens reached 7%, remarkably high given its large public sector and the small size of its native population.24 Bahraini policymakers were concerned that most of the jobs being produced by the private sector were going to foreign workers. To address this problem, Bahrain passed two major labor policies that remain the strongest attempt by a Arab country to close the labor-wage gap between citizens and foreign workers.25

First, in July 2008, Bahrain increased the monthly fee private firms must pay to employ a foreigner from $22 to $49. In Q2, 2009 it introduced an even more impactful reform that allowed all workers, regardless of their nationality, to leave their job at any time.26 Bahrain’s government was able to implement this policy despite opposition from private firms historically dependent on cheap foreign labor.

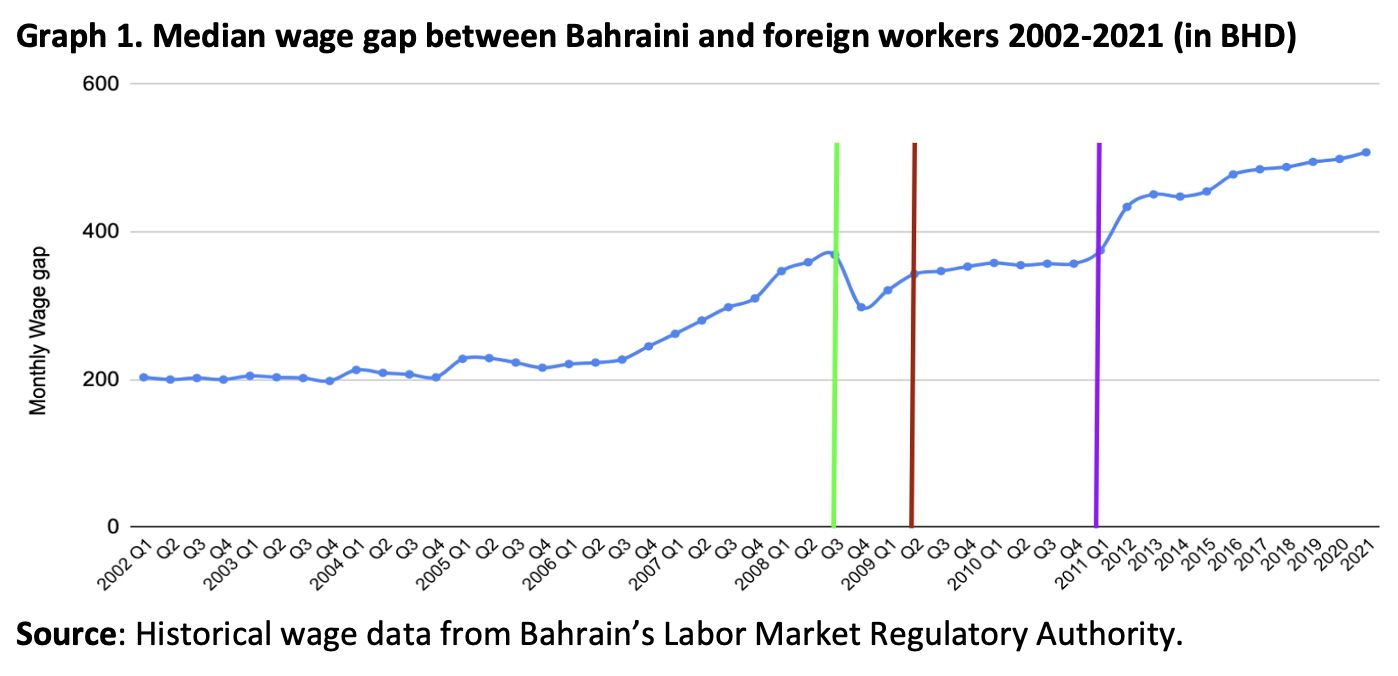

To illustrate the impact of these two labor reforms, I compute the private sector wage gap between national and expat workers’ salaries from Q1, 2002 through Q1, 2021.27 In graph 1, I highlight three main labor policies:

- Increasing monthly fees on firms for hiring expat labor (green line)

- Granting all workers the right to quit their jobs and switch employers (red line)

- Re-introducing labor restrictions on foreign employees due to pressure from the private sector (purple line).28

The graph shows that the labor-cost gap narrowed immediately after the introduction of the first policy.29 The wage gap then rose slightly before stabilizing again after the introduction of the policy to equalize labor mobility (red line).

However, after two years, Bahrain re-introduced policies (purple line) restricting foreign employees’ mobility in the workforce. For example, starting in 2011, foreign workers were required to complete 12 months with their initial employer before being allowed to work for another company in Bahrain.30 Predictably, this widened the wage gap between national and foreign labor. This policy change negatively impacted not only foreign employees but also citizens, as it exacerbated their labor-cost disadvantage.

Lastly, these labor reforms also had a clear impact on unemployment among Bahraini citizens. The domestic unemployment rate declined significantly from around 7% in 2007 to 3.6% in 2010.31 Equal mobility among workers removed a major incentive for private firms to hire expat labor.32 Saudi Arabia can apply the lessons gained from Bahrain’s experience in 2008-11 by equalizing labor mobility, which will not only boost incomes for foreign workers but also reduce unemployment among citizens.

B. Minimum Wage for All Workers in the Private Sector

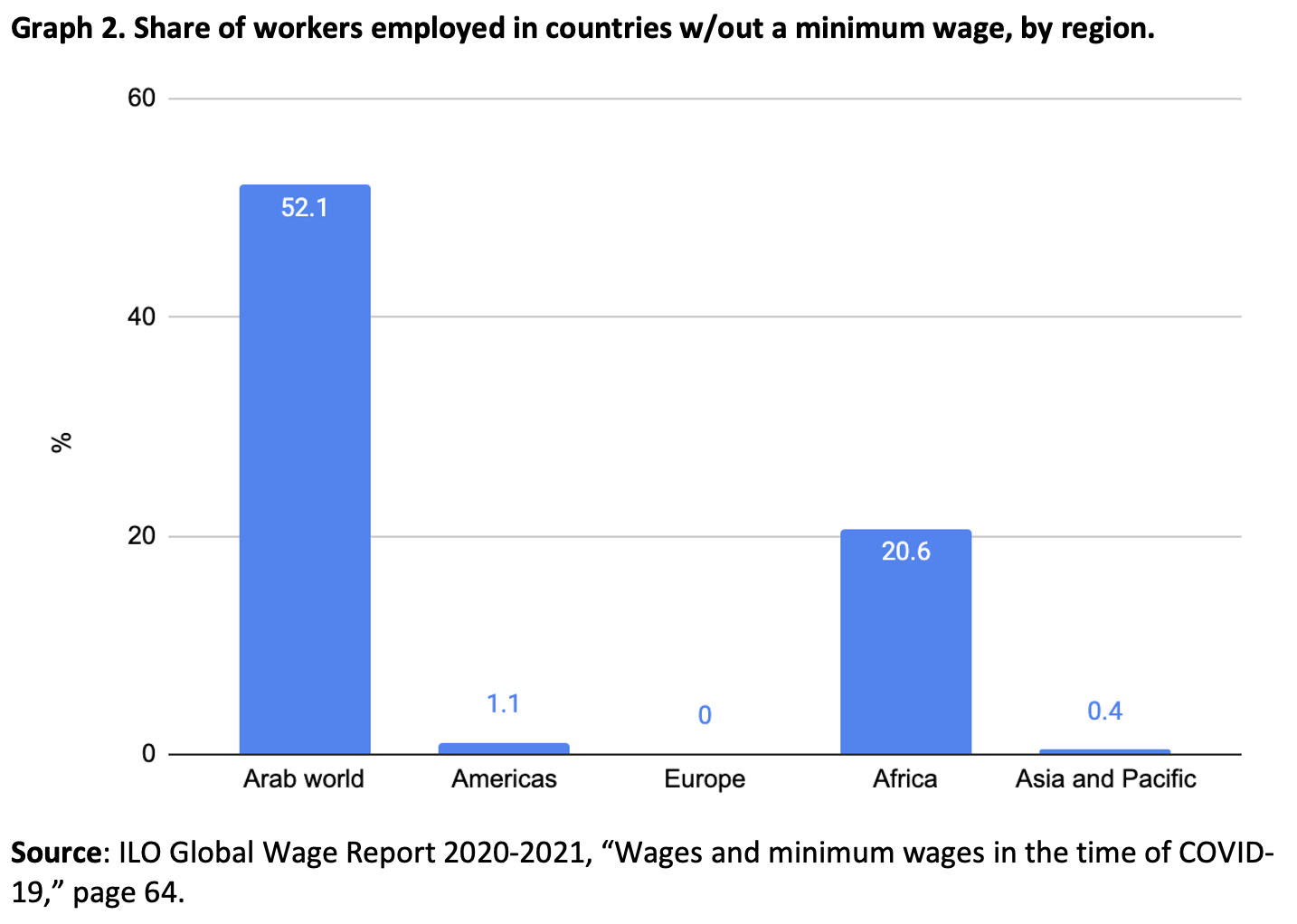

The International Labor Organization’s (ILO) latest Global Wage Report shows that around 90% of ILO member countries have adopted minimum wages either through collective bargaining or through laws set by governments. Introducing a minimum wage for all private sector workers in Saudi Arabia can raise foreigners’ salaries while also reducing unemployment among citizens. Furthermore, countries that strictly impose a minimum wage for public sector but not private sector employees, as is the case in Saudi Arabia, are not classified as having a minimum wage.32

According to an ILO 2021 report, the Arab world has the highest share of workers who are not protected by minimum wage laws.33 Neither citizens nor foreign workers in Saudi Arabia’s private sector are guaranteed a minimum wage.34 The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development requires private firms to pay citizens a minimum of 4,000 riyals per month to count them for the purposes of the Nitaqat program, which imposes quotas for hiring nationals in the private sector.35 However, private firms can still pay citizens below 4,000 riyals. In fact, according to Q3, 2021 GOSI data, nearly 10% of Saudi private sector workers earned less than 4,000 riyals per month. Private employers have even greater power to pay foreign workers less than 4,000 riyals per month, as they are neither required by law to pay more nor are they incentivized by Nitaqat regulations to do so. As a result, about 83% of foreign workers are paid less than 4,000 riyals per month by private firms.36

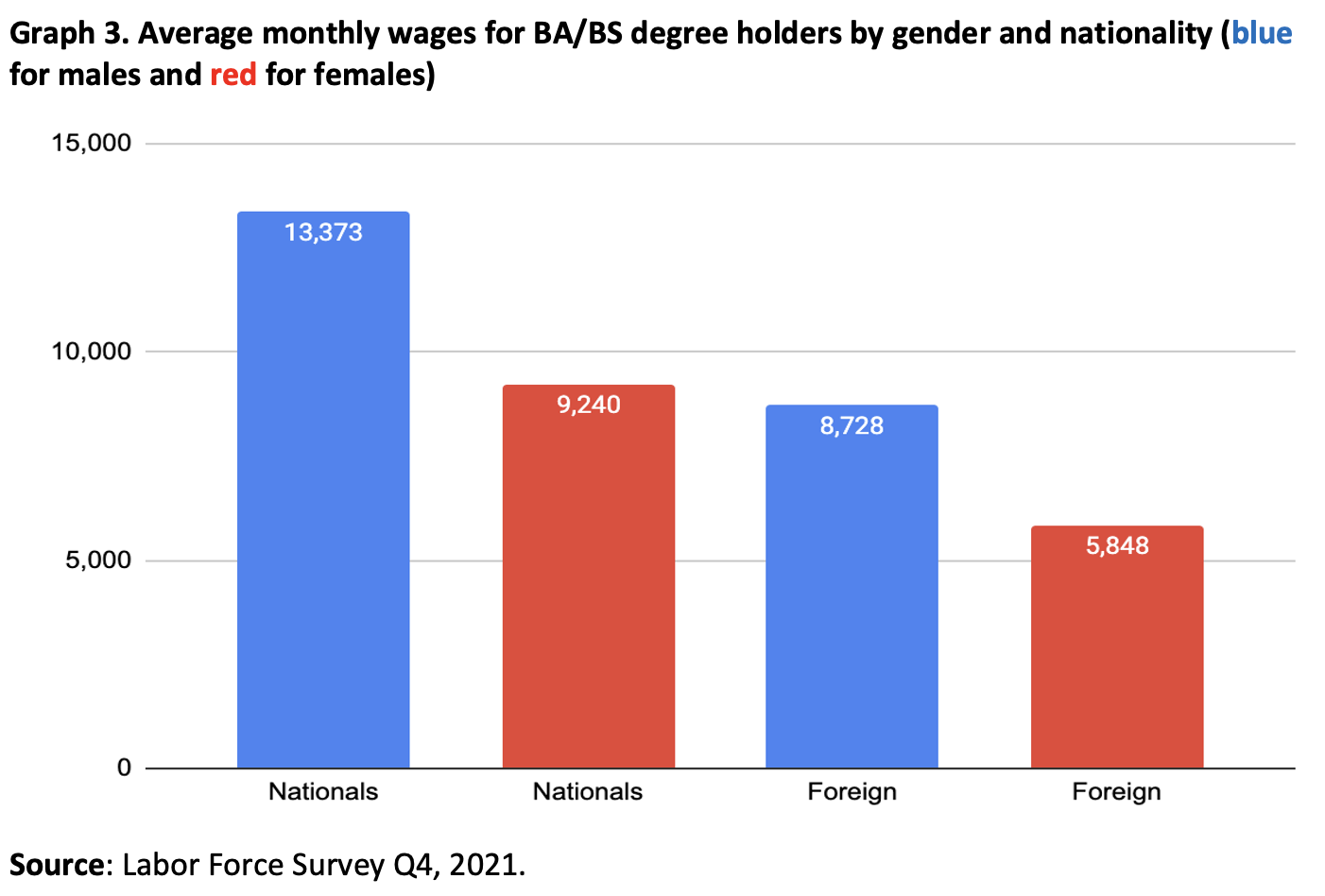

As I argued earlier, a minimum wage could gradually reduce unemployment among citizens, which might appear puzzling at first. Numerous studies on Saudi Arabia’s labor market, such as those by Hertog (2012) and the IMF (2018), suggest that the wage gap harms citizens’ job prospects in the private sector . All else being equal, private companies prefer foreign workers because of their weaker bargaining power.37 Controlling for educational attainment, it is clear that even with equal qualifications, foreign workers are paid less.38 Many Saudis find themselves without work because they are forced to compete against equally qualified, yet significantly cheaper, foreign labor (IMF, 2018).

Can Some Firms be Exempt from Minimum Wage Regulations?

A reasonable concern with regards to a minimum wage in Saudi Arabia is its potentially negative impact on export firms and on companies operating in sectors reliant on low-skill labor. I believe that such concerns are valid and thus argue that some sectors that do not appeal to Saudi workers can be exempted from minimum wage regulations.

One way to determine which economic sectors should be exempted is to look at the share of their employees that are foreign. Table 2 shows that sectors like construction heavily rely on foreign employees, in part because they do not appeal to most Saudis.39 As a result, even if the ministry were to impose a minimum wage on construction firms, they would struggle to fill those jobs with citizens.

Table 2. Economic sectors with the highest dependence on foreign labor

|

Sector |

Share of foreign labor |

|

Agriculture & fishing |

84% |

|

Construction |

85% |

|

Logistics & support services |

85% |

Another group of private firms that could be exempted from the minimum wage policy are Saudi industrial and export companies, as this would boost their labor costs and make them less competitive both regionally and globally . There is precedent for this. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development exempted such companies from expat levy fees in September 2019 and could do the same with the minimum wage.40 Finally, introducing a minimum wage in Saudi Arabia, with some exemptions, would both protect foreign workers and lessen the cost disadvantage of citizens’ labor.

C. Equalizing GOSI Contributions

According to the ILO’s World Social Protection Report for 2021, foreign and national workers in most countries make the same social security contributions.41 For example, in the United States, both citizens and foreign employees are mandated to contribute the same amount.42 This not only ensures equity between all employees but also prevents a situation where one group of workers would suffer a labor-cost disadvantage due to its higher contribution rates. From an employer’s perspective, a higher social insurance contribution rate per worker effectively constitutes a tax on the firm.

Under the existing social security scheme for GOSI, private firms pay a total of 11.75% for citizens: 2% for occupational hazard, 9% for the pension system, and 0.75% for SANED.43 In contrast, private firms are obliged to pay only 2% per foreign worker for GOSI’s occupational hazards plan.44

In other words, if two workers, one foreign and one Saudi, both earn a monthly salary of 10,000 riyals, the employer will need to pay 975 riyals more in monthly GOSI contributions for the Saudi worker, or 11,700 riyals more per year. This differential is only partially offset by annual expat levy fees of 9,600 riyals for firms with a majority of foreign employees and 8,400 riyals for firms with a majority of Saudi employees.

Table 3. Total labor costs for Saudi and foreign workers (riyals)

|

Nationality |

Monthly salary |

Total cost, including all GOSI contributions |

|

Saudi |

10,000 |

11,175 |

|

Foreign |

10,000 |

10,200 |

III. Conclusion

Saudi Arabia has made noticeable progress in the past few years in implementing labor market reforms to make its private sector more competitive. Over time, these reforms have facilitated women’s integration into the workforce. Currently 35.6% of Saudi women participate in the workforce, more than double the rate in Q2, 2016.45 Moreover, unemployment among women declined from 30.2% in Q3, 2020 to around 22.5% in Q4, 2021.46 The employment gains for Saudi women have been partially driven47 by private firms in sectors such as retail and manufacturing, which have replaced foreign labor with female nationals. This occurred as the labor cost for hiring foreign workers increased due to the expat levy fees imposed on firms since 2017, narrowing the labor-cost gap between Saudi females and foreign male employees (see graph 3).

While advances in that area are laudable, the broader labor-cost gap between citizens and foreign employees still desperately needs to be addressed. Unless this peculiarity of the Saudi and GCC labor markets is resolved, citizens will continue losing out to foreign candidates for private sector jobs.

Policy Recommendations

To create a level playing field for citizens in the private sector, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development should implement the three following policies:

- Equalize foreign worker mobility by granting foreign workers the full ability to switch jobs without any restrictions, as is the case for Saudi workers.

- Adopt a universal minimum wage with potential exemptions for certain sectors or firms.

- Require foreign labor and their employers to make GOSI contributions at the same rate as citizens.

Meshal Alkhowaiter is a current first year PhD student at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Meshal was a former Data Lab lead researcher at the World Bank Group, focusing on labor market issues in the Arab world. Prior to that, Meshal worked with a research center with the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (formerly the Ministry of Labor).

Main photo: Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images.

MEI is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.

Endnotes

1. International Monetary Fund. Saudi Arabia: 2021 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report:

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2021/07/07/Saudi-Arabia-2021-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-461736

2. Is Saudi Arabia entering a “Great Reshuffle”?

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2022/01/31/is-saudi-arabia-entering-a-great-reshuffle

3. Alkhowaiter, 2021. Exploring the rising workforce participation among Saudi women. https://www.mei.edu/publications/exploring-rising-workforce-participation-among-saudi-women

4. LFS Q4, 2021: https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/814

5. IMF (2018): https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2018/264/article-A002-en.xml

6. World Bank Group on Saudi labor reforms:

https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/saudi-arabia-announces-major-reforms-its-migrant-workers

7. Author’s calculation of data from Bahrain are publicly accessible through the Labor Market Regulatory Authority.

8. GOSI contribution benefits: https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Coverages&locale=en_US#:~:text=The%20rate%20of%20contribution%20to,and%20the%20contributor%20pays%209%25.&text=The%20Occupational%20Hazards%20Branch%20applies%20mandatory%20to%20Saudis%20and%20non%2DSaudis.

9. ILO report on Social Protection 2020:

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_817574.pdf

10. Hertog 2014. Arab Gulf States : an assessment of nationalisation policies. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/32156

11. Bahrain: إلغاء نظام الكفيل رسميا مع تطبيق «حرية انتقال العامل http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/50588.html

All data from Bahrain are publicly accessible through the Labour Market Regulatory Authority.

12. https://www.arabnews.pk/node/1825046/saudi-arabia

13. ﺗﺤﺴﻴﻦ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺔ اﻟﺘﻌﺎﻗﺪﻳﺔ - وزارة الموارد البشرية

https://hrsd.gov.sa/sites/default/files/5112020.pdf

14. Supra note at 1. IMF 2021

15. تعرف على خطوات تنفيذ «خدمة التنقل الوظيفي» عبر قوى https://www.okaz.com.sa/news/local/2061336

16. . ﺗﺤﺴﻴﻦ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺔ اﻟﺘﻌﺎﻗﺪﻳﺔ - وزارة الموارد البشرية: خدمة الخروج والعودة

Provision 6.

https://hrsd.gov.sa/sites/default/files/5112020.pdf

17. IMF 1995. Labor Market Challenges and Policies in GCC. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/FT/gcc/GCC3.pdf

Hertog 2012. “A comparative assessment of labor market nationalization. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46746/1/A%20comparative%20assessment%20of%20labor%20market%20nationalization%20policies%20in%20the%20GCC%28lsero%29.pdf

Hertog 2014. “Arab Gulf states: an assessment of Nationalisation Policies”. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/32156/GLMM%20ResearchPaper_01-2014.pdf?sequence=1

18. IMF 2018. “Labor Market Reforms to Boost Employment and Productivity in the GCC”.https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/100513.pdf

19. Saudi Arabia Labor force survey Q4, 2021. Table 4. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/814

20.. تذبذب «رسوم العمل» أجّل إلغاء «الكفيل» و«البحرنة

http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/162772.html

21. Saudi Arabia Labor force survey Q4, 2021. Table 5-7.

22. Approximately 75% foreign labor have a HS degree or less. Table 8. LFS Q1, 2021.

http://blmi.lmra.bh/2021/03/data/gos/Table_08.pdf

23. The wage differential is based on labor force survey data and is measured to standardize the differences in the local currency at each country. The wage rate differential is computed as: Average wages for nationals divided by average wage for foreign labor. Computed as=Nationals wage/ foreign labor wage.

24. البطالة في الوطن العربي حقائق وأرقام

https://www.al-jazirah.com/2007/20070121/rj9.htm

25. Supra note at 16.

26. Supra note at 9.

27. This is calculated as the difference between average monthly wages for citizens and foreign labor. A large amount signifies a larger wage gap between the two groups.

28. Labor market data in Bahrain from 2002-10 are quarterly, but only annual data are available from 2011 onwards.

29. The data here are derived from aggregate figures, and thus I cannot control for time-varying factors such as Bahraini and foreign workers’ educational attainment, which may influence the wage gap between the two groups. For example, one likely factor that may influence relative wages, but that we cannot control for is that Bahraini private firms may have recruited less low-skilled foreign labor once full worker mobility was granted because the main reason for hiring them (i.e. cost) has been eliminated. This may in turn cause the “median wage” for foreign workers to rise due to changes in the composition of existing foreign labor where remaining foreign labor are more skilled than pre-reforms and thus have higher wages.

30. Labor Market Regulatory Authority.

https://lmra.bh/portal/ar/page/show/194#:~:text=%D9%81%D9%8A%20%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D8%B7%D9%84%D8%A8%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%86,%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85%20%D8%A5%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%A7%D9

31. انخفاض معدل البطالة الى. 3.6%

http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/511462.html

32. There is little evidence showing that the unemployment declined due to additional state-hiring, because public employment only grew by 3.5% between 2007 through 2010, or 1,273 government jobs. Bahrain Civil Service Bureau. Table 5 http://blmi.lmra.bh/2021/03/data/csb/Table_05.pdf.

33. ILO Global Wage report 2020-2021, pages 61-62.

34. ILO Global Wage report 2020-2021, page 64.

35. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development requires private firms to pay citizens a minimum of 4,000 riyals/month to count nationals for Nitaqat program purposes (i.e. nationalization quotas in the private sector). However, private firms can still pay citizens below the 4,000 riyal amount.

36. Can Hiring Quotas Work? The Effect of the Nitaqat Program on the Saudi Private Sector.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20150271

37. Author’s analysis of GOSI Administrative data Q3 2021:

https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Open_Data_Library&locale=en_US

38. Studies on the wage gap between nationals and foreign labor in Saudi Arabia:

Hertog (2012)

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/9693353.pdf

IMF (2018):

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2018/264/article-A002-en.xml

39. Author’s analysis of Labor Force Survey data Q2, 2021:

https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/814

40. Labor Force Survey Q3, 2021: https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/814

41. MHRS excludes Industrial exporting firms from the expat levy fee:

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-economy-industrial-idUSKBN1W91WU

42. ILO’s World Social Protection 2021 report:

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_817574.pdf

43. U.S. Social Security Administration:

https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/cbb.html

44. GOSI Contribution rates for citizens and GCC nationals:

https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Unemployment_Insurance_(SANED)?locale=en_US

45. GOSI Occupational Hazards scheme:

https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Occupational_Hazards_Branch&locale=en_US

46. Alkhowaiter, 2021. Exploring the rising workforce participation among Saudi women. Middle East Institute:

https://www.mei.edu/publications/exploring-rising-workforce-participation-among…

47. LFS Q4, 2021: https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/814

References

Aljazirah newspaper 2007 . البطالة في الوطن العربي حقائق وأرقام

Alkhowaiter, 2021. Exploring the rising workforce participation among Saudi women. Middle East Institute.

Alwasatnews. تذبذب «رسوم العمل» أجّل إلغاء «الكفيل» و«البحرنة

Alwasatnews. Bahrain: إلغاء نظام الكفيل رسميا مع تطبيق «حرية انتقال العامل

Approximately 75% foreign labor have a HS degree or less. Table 8. LFS Q1, 2021.

Author’s analysis of GOSI Administrative data Q3 2021:

Bahrain Labor force statistics. Wage differentials. Table 25. http://blmi.lmra.bh/2021/03/data/lmr/Table_25.pdf

Bahrain Unemployment rate drops. انخفاض معدل البطالة الى 3.6%

Based on Labor Force Survey Q3, 2021.

GOSI contribution benefits: https://www.gosi.gov.sa/

GOSIOnline/Coverages&locale=en_US#:~:text=The%20rate%20of%20contribution%20to,and%20the%20contributor%20pays%209%25.&text=The%20Occupational%20Hazards%20Branch%20applies%20mandatory%20to%20Saudis%20and%20non%2DSaudis.

GOSI Contribution rates for citizens and GCC nationals:

GOSI Occupational Hazards scheme:

Hertog 2012. “A comparative assessment of labor market nationalization. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46746/1/A%20comparative%20assessment%20of%20labor%20market%20nationalization%20policies%20in%20the%20GCC%28lsero%29.pdf

Hertog 2014. “Arab Gulf states: an assessment of Nationalisation Policies”. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/32156/GLMM%20ResearchPaper_01-2014.pdf?sequence=1

Hertog 2014. Arab Gulf States : an assessment of nationalisation policies. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/32156

http://blmi.lmra.bh/2021/03/data/gos/Table_08.pdf

http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/162772.html

http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/50588.html

http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/511462.html

https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/saudi-arabia-announces-major-reforms-its-migrant-workers

https://hrsd.gov.sa/sites/default/files/24112021.pdf

https://lmra.bh/portal/ar/page/show/194#:~:text=%D9%81%D9%8A%20%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D8%B7%D9%84%D8%A8%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%86,%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%84%20%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85%20%D8%A5%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%A7%D9

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20150271

https://www.al-jazirah.com/2007/20070121/rj9.htm

https://www.arabnews.pk/node/1825046/saudi-arabia

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-16/saudi-arabia-implements-expat-labor-reforms-with-caveats

https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Occupational_Hazards_Branch&locale=en_US

https://www.gosi.gov.sa/GOSIOnline/Unemployment_Insurance_(SANED)?locale=en_US

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_817574.pdf

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/--ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_817574.pdf

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2021/07/07/Saudi-Arabia-2021-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-461736

https://www.mei.edu/publications/exploring-rising-workforce-participation-among…

https://www.okaz.com.sa/news/local/2061336

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-economy-industrial-idUSKBN1W91WU

https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/cbb.html

https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/814

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2022/01/31/is-saudi-arabia-entering-a-great-reshuffle

ILO report on Social Protection 2020,

ILO’s World Social Protection 2021 report:

IMF 1995. Labor Market Challenges and Policies in GCC https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/FT/gcc/GCC3.pdf

IMF 2018. “Labor Market Reforms to Boost Employment and Productivity in the GCC”.https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/100513.pdf

International Monetary Fund. Saudi Arabia: 2021 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report:

Is Saudi Arabia entering a “Great Reshuffle”?

Labor Force Survey Q3, 2021: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/LMS%20Q03%202021A-Final_2.pdf

Labor market data in Bahrain from 2002-2010 are quarterly, but only annual data are available from 2011 onwards.

Labour Market Regulatory Authority.

LFS Q3, 2021: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/LMS%20Q03%202021A-Final.pdf

MHRS excludes Industrial exporting firms from the expat levy fee:

Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development Guidance on Expat Levy fees:

Okaz Newspaper. تعرف على خطوات تنفيذ «خدمة التنقل الوظيفي» عبر قوى

Peck 2017. Can Hiring Quotas Work? The Effect of the Nitaqat Program on the Saudi Private Sector.

Saudi Arabia implements expat labor reform.

Saudi Arabia Labor force survey Q4, 2021. Table 4.

Saudi Arabia Labor force survey Q4, 2021. Table 5-7.

Saudi Arabia Labor force survey Q4, 2021. Table 6-1.

Saudi Arabia’s labor reform on expat labor mobility.

U.S. Social Security Administration:

World Bank Group on Saudi labor reforms: