Summary

In Iraq the issue of decentralization tends to kick up a flurry of activity and discussion whenever Law 21 is amended or a governor attempts to create a new region. Otherwise though, federalism only draws attention as it relates to Baghdad-Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) relations, oil revenue sharing, or both. However, while federalism rarely lends itself to meaningful discussion beyond Baghdad-KRG dynamics, Iraq’s current public service regime is struggling to deliver on desperately needed services in part due to the issue of establishing a functioning federal state system across the country. Far more attention needs to be devoted to institutions and how those operating within them can deliver those services. One way to do this is to decentralize service provision to the governorates not incorporated into a region. However, this process has been hampered by administration, fiscal, and political issues. Identifying these and seeking solutions to resolve them will be key. This paper addresses the decentralization process, specifically focusing on the issues surrounding the governorates not incorporated into a region, as per Law 21.

Introduction

In Iraq the issue of decentralization tends to kick up a flurry of activity and discussion whenever Law 211 is amended2 or a governor attempts to create a new region. Otherwise though, federalism only draws attention as it relates to Baghdad-Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) relations,3 oil revenue sharing,4 or both. However, while federalism rarely lends itself to meaningful discussion beyond Baghdad-KRG dynamics,5 Iraq’s current public service regime is struggling to deliver on desperately needed services in part due to the issue of establishing a functioning federal state system across the country. Countless articles and op-eds underline the need for good governance in Iraq and functioning services, but far more attention should be devoted to institutions and how those operating within them can deliver those services.

One way to do this is to decentralize service provision to the governorates not incorporated into a region. However, this process has been hampered by administrative, fiscal, and political issues. With that said, federalism and decentralization are constitutional and in law. The capacity of the governorates is growing with time, and some gains have been made. To try to recentralize and step back from decentralization toward another model would not address the fundamental issues that Iraq is facing. Thus, identifying the problem areas and seeking and implementing solutions to resolve them is the only way to capitalize on gains made. This paper addresses the decentralization process, specifically focusing on the issues surrounding the governorates not incorporated into a region as per Law 21 of 2008. Oil sharing,6 Baghdad-KRG relations, and intra-KRG relations warrant an in-depth discussion and will be left to another time.

History

To start, it is important to consider the history of Iraqi institutional capacity and budgeting.7 Since 2005, the Iraqi government’s organization and efficacy has evolved considerably. The Iraqi federal government in 2005-06 had a very rudimentary capacity to budget and largely relied on pen, paper, and FoxPro, a basic and dated computer program. At this point, Baghdad could only account for one fiscal year of projections on revenues and expenditures, rather than multi-year spending estimates.8 Additionally, the governorates lacked executive strength, budgeting capacity, and legislative experience in the newly-established Provincial Councils (PCs).

However, in the ensuing years, Iraq would witness wide-ranging changes to this system. Parliament secured a say in the Iraqi federal budget, authorities established the Accelerated Reconstruction and Development Program (ARDP) as a nascent form of fiscal federalism, the Ministry of Finance developed the capacity over the years to take hold of the budgetary process, which under the Ba’athists was controlled by the Ministry of Planning, and governorates earned the right to budget for, and ask the federal government for, specific funds to be allocated to the governorates for projects.9 The Iraqi government can now develop and implement federal budgets despite challenges like the pre-existing institutional culture, turnover of staff and ministers, capacity deficits, violence, and a radical shift toward federalism. With that said, there remain issues to address and overcome, and the progress of federalism as a model for service delivery in Iraq has waxed and waned since 2005. For example, capacity is growing to execute on budgets, but there is still no investment budget to execute on in the provinces. Additionally, budgetary execution rates have sat around 65 percent since 2015,10 and protests over poor services and unemployment continue to wrack the Iraqi state.

Federalism as a concept is deeply unpopular across most of Iraq,11 as many fear it will empower corrupt local politicians and interests while failing to improve services. Previous protests in Iraq made clear citizens’ distrust and anger with local politicians through the targeting of PC buildings and political party offices. For example, the massive 2011 “Day of Rage” protests targeted local politicians and provincial offices, burning down PC buildings in some governorates (which notably happened again in the protests of 2018).12 Further, some see Iraq as a de-facto federacy, meaning that the federal government has one set of federal relations with the KRG, and a symmetrical approach with the provinces not incorporated into a region.13 Nonetheless, the Iraqi government is slowly attempting to move away from such thinking. For example, in 2015, former Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi issued an executive order to implement Law 21. The law had been passed in 2008 with the goal of empowering the governorates through decentralization. This pushed forward various administrative reforms, affecting six different federal ministries.14 However, the decentralization process has been poorly executed with some federal ministers reluctant to see it enacted, while the war against ISIS and the ensuing financial crisis in 2014-15 significantly hampered decentralization initiatives. These issues have been exacerbated by many other underlying structural concerns, such as endemic corruption, politically driven distribution of oil revenues, and mismanagement of state assets and resources.

"In theory, Iraq can be very decentralized. Articles 122 and 123 of the 2005 Constitution allow for the governorates to determine their level of decentralization (in negotiation with Baghdad) so long as this is in accordance with its legal framework."

What is the objective of federalism in Iraq?

After the establishment of the 2005 Constitution, the conceptual design of Iraq was that of a decentralized model following the principle of subsidiarity, allowing for asymmetrical relationships between the governorates and Baghdad. The goal of this was to recognize that the needs of the governorates differ from one another; the needs of Diwaniyah differ from those of Basra, and again from Ninewa. Furthermore, asymmetry has a very important political function; Baghdad’s relationship with the KRG is necessarily different because of history and politics. To treat some of the governorates the same as the KRG, or even the same as each other, is to both ignore reality and the politics driving federalism. This is what allows federalism in Iraq to be adaptive as the country progresses. Once paired with subsidiarity, the governorates should in theory deliver their services in a timely and efficient fashion, tailored to their own needs and circumstances. Overall, decentralized asymmetrical federalism, in principle, should allow the Iraqi federal government, the KRG, and the governorates not incorporated into a region to manage inter-governorate/region or governorate-Baghdad issues to settle disputes and improve governance.

What is the legal design of federalism in Iraq?

Iraq’s constitution creates a federal system of 18 governorates, three of which consist of territory governed by the KRG in what is currently Iraq’s only region. As per Article 119, one or more governorates can hold a referendum and form a region. Regions operate with their own constitution (provided that it does not contradict the 2005 Constitution), which defines the region’s structure of powers, authorities, and mechanisms, and outlines how such powers may be exercised (Article 120). Article 121 provides that regions are responsible for the creation and administration of internal security forces and police, outside of federal forces. This is the article that legally allows the Peshmerga and Asayish in the Kurdish Region of Iraq. To note, the Hashd al-Shaabi — or the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) — are separate from Article 121. This umbrella organization was institutionalized with the passage of a special law in 2016 by the Iraqi Parliament. Under this law, the PMF is an independent organization with a corporate personality, is part of the Iraqi armed forces, and reports to the prime minister (whose role includes commander-in-chief), with a commander being appointed by Parliament. The PMF law draws from Articles 61 and 73 of the Constitution.15

Concerning the governorates, Article 122 for Governorates not Incorporated into a Region provides that governorates “… shall be granted broad administrative and financial authorities.” The 2005 Constitution also allows for an asymmetrical federal system between the central government and the governorates not incorporated into a region, as per Article 123. This allows governorates to have as much devolution (or as little) as they wish, conditional on the acceptance of both the governorate and federal government. Where disputes are concerned regarding shared power arrangements, Article 115 gives legal supremacy to regional and governorate governments over the federal government in Baghdad. If powers do not specifically fall under the legal mandate of the federal government, the governorates can exercise authority. Article 121 allows regional authorities to override federal laws should those laws fall outside the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government.

Law 21, passed in 2008, was an attempt to decentralize some ministries to the governorates to effectively kickstart the decentralization process. It was revised in 2011, 2013, and again in 2018,16 but has yet to be fully implemented. To facilitate this process, the Parliament Committee on Regions and Provinces not Incorporated into a Region is empowered by Article (98) of the Bylaws of the Iraqi Council of Representatives to monitor the affairs of those regions and governorates that are not incorporated into a region and to manage the relationship of these governorates with the federal government. The High Commission for Coordinating among the Provinces (HCCP) is another body involved in assisting in the decentralization process. This entity — established by Law 21, Article 45 — is chaired by the prime minister and includes ministers, governors, and chairs of provincial councils.17 It is tasked with transferring various departments and responsibilities from the ministries to the provinces, along with funding and staff, as well as coordinating among the provinces on local administration and tackling problems and obstacles faced.18

In theory, Iraq can be very decentralized. Articles 122 and 123 of the 2005 Constitution allow for the governorates to determine their level of decentralization (in negotiation with Baghdad) so long as this is in accordance with its legal framework. The federal government is granted superseding powers and authorities with regards to certain matters, but all other matters (unless legally justified) fall under the jurisdiction of the governorates, as defined in Article 115. So post-2005 and after the order was given to decentralize, we see a system shift from a centralized model of governance where the provinces acted as more of administrative entities that delivered on services as decided and funded in Baghdad to one where authorities were expected to be at the provincial level. However, in practice, this required a deep administrative structural change, as well as political change, to a new system of governance in Iraq. As the process progressed, impediments emerged.

"[The paperwork] hangover of the centralized Ba’athist era must go if a decentralized model of federalism in Iraq is to move forward, and timely services are to be provided anywhere."

Administrative and financial impediments

In referring to administrative and financial impediments, it is important to separate the issues into four categories: operational, investment, administrative/process, and revenue. Operational and investment refer to budgeting, with operational budgeting accounting for staff salaries, fuel, and machinery upkeep, while investment refers to project payments, new contracts, and land purchases. Administrative and process issues focus on how government works as an organization both internally and externally with respect to organizational structures, processes of reporting, reporting structures internally, and revenue generation externally as a means to fund government operations. Revenue refers to the means by which the Iraqi government funds itself via tax, toll, or fee. These different functions overlap with each other in how they effect outcomes and the effectiveness of the governorates, but for the sake of clarity I will discuss them individually.

Operational budgeting

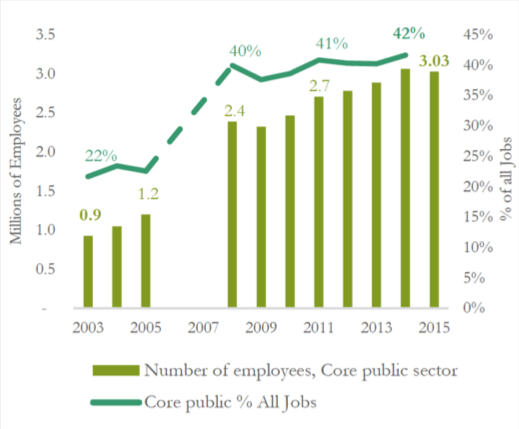

As the six federal ministries devolved authorities, governorates suddenly saw a rapid growth of employees in their directorates that were devolved from federal ministries. For example, the governorate of Baghdad expanded from 90,000 employees to 325,000 because the ministries of Health and Education, as in most states, have huge numbers of staff on payroll.19 As such, the operational budget cost rose sharply (see Chart 1). Due to regular hiring and “ghost employees,” 2018 saw an addition of 46,000 people to the total public sector payroll.20 Concerning the operational budget overall, according to Finance Minister Fuad Hussein, the Iraqi public sector has grown to 6.5 million people, compared to 850,000 pre-2003.21

As the operational budget continued to inflate, it drew money away from the investment budget as directorates sought to cover salaries, sometimes resulting in erratic payments or a total absence of pay: for example, the staff of the agriculture directorate function completely as volunteers in Maysan, and in Diwaniyah, youth and sports cannot afford to pay for security to guard properties owned by the directorate, leading to damage or takeover from trespassers.22 This can have very real political and economic consequences: the lack of funding and ability for the governorates to perform tasks like policing and watching buildings creates the space for militias to take over them, resulting in de-facto land and resource control and further swaying local politics.23 In a discussion around scaling up the ability for a specific service to grow in Iraq, the owners of the service provider complained how buildings that they wanted to rent were being occupied by specific militias who demanded they pay a second tax. They were also told to work from the roof of the building.24 The inability of the ministries or the governorates to police their buildings enables them to be used for illicit activities and strengthens the militias.

Furthermore, as payroll grows, local revenues are not fully developed (which will be discussed more in-depth shortly) and even the operational budget faces issues. Some directorates have had to shift funding away from maintenance, causing fuel shortages for cars, degradation of machinery, and even critical infrastructure25 disuse, further impacting directorate effectiveness and thus public services.

Chart 1: LHS: Core Public Sector Employment 2003-15, RHS: Government Wage Bill26

Investment budgeting

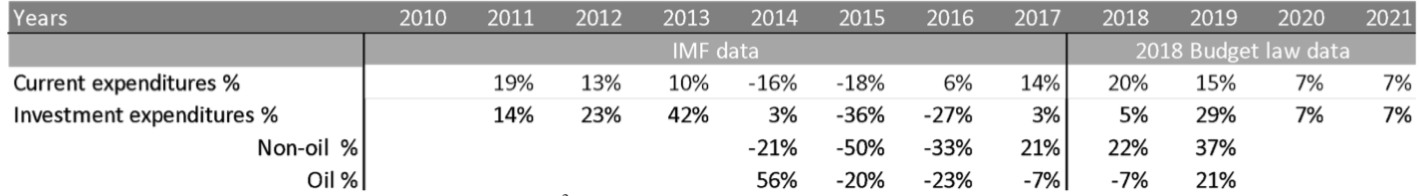

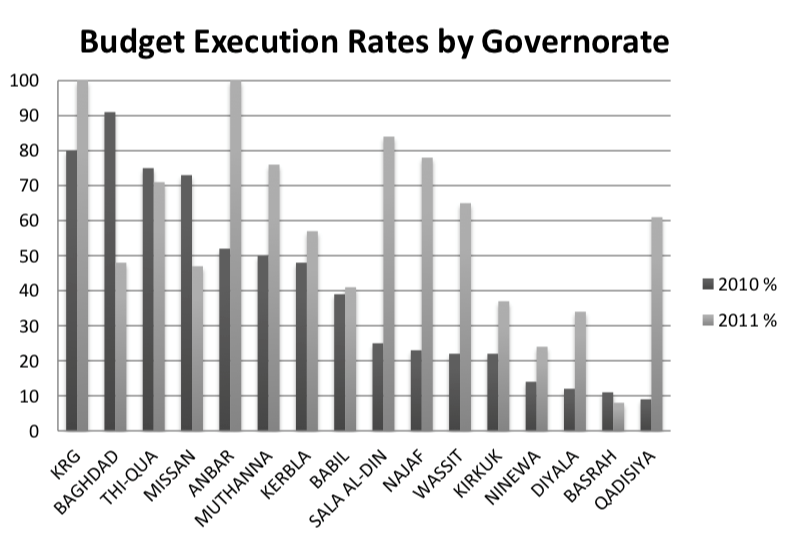

The investment budget across Iraq at the federal level has consistently faced a deficit (Tables 1 and 2 below27), as the state has had to shift funds in response to oil price fluctuation (as it is highly dependent on oil revenues), terrorism, and violence over the years.

As Tables 1 and 2 show, investment budgeting has been consistently low, with oil investments accounting for the majority of the investment. Even so, Ministry of Finance data shows that expenditures for investment budgets were significantly lower than budgeted figures.28 When examining non-oil investment funding, the numbers are even lower than they appear, as they also account for arrears to contractors on multi-year projects that have been slowed by fiscal-year-based budgeting. Also, as Ahmed Tabaqchali points out:

“Productive investment spending (such as those on electricity, water, housing and education) accounted for 33-75 percent of all non-oil spending during the three years 2015-2017. The rest of non-oil investments during these years were investment spending by the Council of Ministers, Ministry of Interior, and non-ministerial entities which accounted for 67-25 (sic) percent of total non-oil investments.”29

This has become an endemic problem in the governorates, which have not been receiving their investment budget funding. Such funding gaps impede them from signing off and executing on any contracts, effectively confining the real executive powers to the authorities in Baghdad.

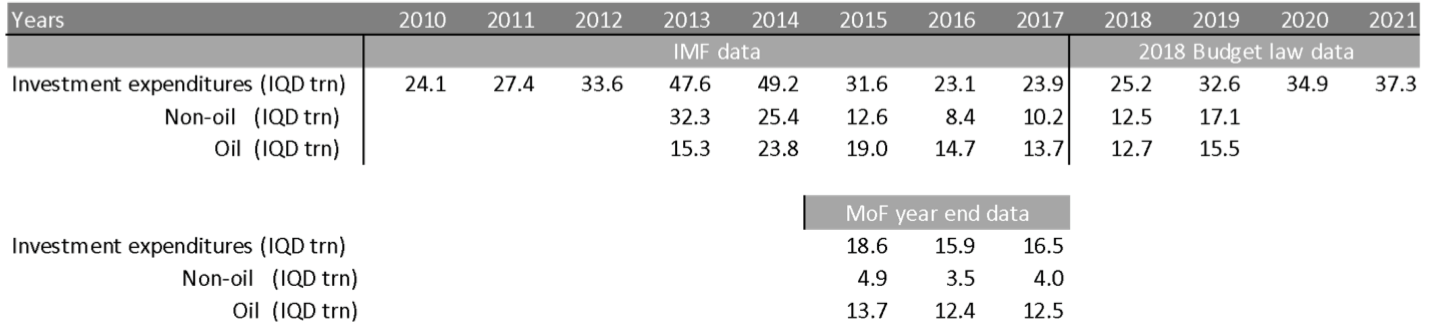

Additionally, as alluded to before, the execution rates of the budgets in Iraq at the governorate level have been relatively sub-par. While capacity has grown considerably with time, some of the governorates still struggle with effective budget execution and procurement, as shown in Table 3. It is also important to note that while this information was gathered by the UN, its accuracy is questionable (e.g. KRG and Anbar reporting 100% execution rates). Additionally, tracking execution rates as money is spent has been an ongoing issue, but many of the governorates lack a sufficient means to follow up on the downstream project process to gauge the impact of the money being spent. It is often unclear whether or not the money has had a tangible impact. This is partially due to capacity issues, poor organization, and political interference.

Table 3: Budget execution rates by governorate + KRG, 2010-1130

Concerning contracts for projects like land development, funds delivered to the governorates such as the ARDP and the Provincial Development Plan (PDP) offer a useful method to fund projects proposed by the governorates (notably in the current structure the governorates still must obtain approval before they can execute on projects). From the World Bank:

“…from 2006–2009, the Governorates and the KRG together were allocated 35 to 45 percent of the total federal investment budget to implement projects selected and developed within the Governorates (and the KRG). When federal budget shortfalls occur, ministry investment budgets are more protected at the expense of allocations to Governorate investments. In the 2016 federal budget, the regional development allocation to the KRG and the Governorates will amount to only 6 percent of all federal investment expenditures.”31

To make matters more problematic, the delivery of funding is erratic. As a director of municipalities pointed out, they did not receive their ARDP funding that was meant to be delivered at the beginning of the 2017-18 fiscal year until December 20, 2018. This greatly limited their ability to pay for contracts, resulting in a start-stop cycle of projects, frustrating contractors, and leading to delays. Additionally, they only received less than a fifth of what was approved, most of which was quickly shifted away from investments and projects toward operational (salary) gaps.32 The lack of a reliable funding source also impacts the ability of the directorates to plan for, structure, and execute on projects and deliver services.

Revenue generation

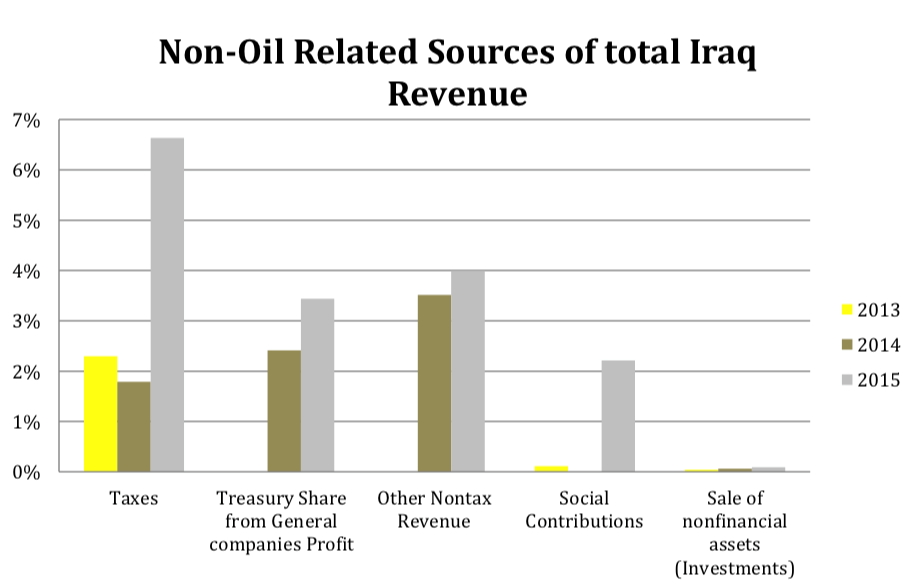

The governorates lack a broad means of revenue generation. In looking at all of Iraq, revenue diversification outside of oil is a consistent issue (see Table 4). While Article 44 of Law 21 outlines the different means by which the governorates can collect revenue, the Ministry of Finance has enforced a decision that they must establish a budget which includes revenues before they can collect and place those revenues into a revenue account. This is hampered when the PC fails to legislate laws to encourage the development of localized revenues (via tolls and fees for services) and the federal government does not disclose just how much money is being gathered through areas like border trade (of which the governorates are owed 50 percent). Thus far, most of the revenues accrued in the governorates (excluding petro-dollars) are those from self-funding directorates, such as municipalities, via the collection of tolls and fees for services. From a national perspective however, these own-source revenues are miniscule: in 2014 in Babel, they accounted for less than one hundredth of a percent.33 In cases where governorates have suggested or created new means for revenue generation in line with Law 21, what would be gained by the governorate would result in a reduction from federal budget allocations, limiting the incentive to diversify.34 To try to get around this impasse in the short term, some governorates have created an account that is linked to the PC, although the money sent to that account is often stolen or utilized for inappropriate projects.

While some governorates have looked at different ways to diversify revenue, such as the “pilgrims tax” in Karbala (comparable with the tourist fees charged in some other cities like Rome), societal norms against charging religious pilgrims for local infrastructure upkeep as well as the pragmatic means of collecting the funds have prevented the governorate from adopting it as a revenue source.

Table 4: Non-Oil-Related Sources of Total Iraq Revenue, 2013-15.35

Administration and process

Within the governorates, new structures had to be created to absorb the new authorities and personnel shifting from the federal ministries to the provincial level. Once stood up, these new institutions have caused various problems, specifically in the governorates’ relationship with Baghdad.

First, there has been a haphazard decentralization process resulting in inefficient staff allocation. For example, one director general (DG) complained to me that they received eight lawyers, but no accountants at all, when they needed just one lawyer and a team of three accountants. As a side effect of this ad-hoc and poorly managed process, multiple reporting structures are often established, so DGs receive official letters from the PC, the governor’s office, and the federal ministries requesting that they complete different tasks. Other issues are more related to the context in which decentralization has taken place. For example, the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs transferred three sections of the ministry to governorates, but the Ministry of Finance allocated a budget to each one separately, creating a situation whereby there are three separate budget accounts for a single directorate. Another example is that within the governorates, no single person is responsible — and thus can be held accountable — for the financial affairs of the governorate, as the financial advisor in the governor’s office and head of Administrative and Financial Affairs Directorate have overlapping roles.

As a result, this has created confusion over the roles of governorate and federal reporting structures. As the DGs can receive multiple, potentially conflicting orders from different sources, they are also scrutinized for corruption or for failing to perform their duties by the inspector general as well as the Integrity Commission. As Doherty put it in a report to a USAID-funded project focused on decentralization, “[p]olicy confusion, lack of rules defining authority and procedures, and fear of sanction or prosecution for positive action stymie provincial governments.”36 When one actor does not get their way, they can leverage the commission or the inspector general to act — or, in the case of the PC, pressure the governor to remove the individual in question. This is largely why the Directorate of Health in Diwaniyah has seen 10 DGs since 2003.37

To add to the complexity, the federal Health and Education ministries’ ongoing decentralization process was stopped mid-way by the previous administration’s ministers. This has created significant confusion in the governorates, as there is now a legal gray area and uncertainty: are the staff and authorities that have been decentralized to the governorates still under the control of the governorate, or are they reverting to the federal ministry? If staff receive orders from both the ministry and the governor’s office, which should they follow? This has significantly hampered these services in the governorates, and has resulted in unnecessary conflict, such as when the previous minister of health opened a cancer ward in Maysan in 2018 without even informing the governor’s office, despite the ward being technically under the purview of the governorate. Confusing matters further, in June 2019 the Council of Ministers won an administrative court case in Diwaniyah to reinstate their candidate as the DG of education after the governor had replaced them with his own candidate.38 This further develops the legal precedent of federal overstep into the governorates in choosing DG level positions. Similar occurrences have happened in Maysan, as an appeal filed by the PC concerning who has the right to appoint senior positions (DGs and above) was rejected by the Federal Supreme Court in 2018, establishing a precedent that only the Council of Ministers has the ability to appoint those positions.39 While PCs certainly engage in corruption and self-interest in the placing of personnel in patronage positions, this legal precedent works against the goal of decentralization.

Within the governorates themselves, the governors and their DGs/directors lack the flexibility to shift funds. While they can request to shift some operational funding concerning staffing (and this is a very limited percentage), much of the funding delivered to the governorates is pre-approved by the federal ministries, which ear-mark it for specific initiatives as set by Baghdad. This lack of horizontal transfer authority further inhibits the governorates from taking on their responsibilities and tailoring their resources toward the wants and needs of their citizens.40

As part of the 2019 federal budget, the federal government announced that it would maintain control over projects that are up to 90 percent complete before decentralizing them, even those connected to the decentralized ministries. There are hundreds of such projects in the country, and while transferring them immediately would place an unacceptable economic burden on the governorates, at the current rate of progress, these projects are not being completed and will remain in the hands of the federal government indefinitely. This leads to an ongoing lack of transfers of staff and authorities to the governorates.

Issues permeate the functional relationship between the directorates and the ministries. While the directorates can develop and create their own budget, with assistance and coordination from the Provincial Planning and Development Council, budgets sent to the Ministry of Planning and Ministry of Finance have been ignored or drastically changed — often to the point where the directorate effectively lacks the financial means to decide which programs and projects to engage with and how.41 This is a further illustration of how the real authority still lies with the federal government.

Lastly, some old processes have remained that should be adapted or entirely removed. One such process is that different ministries refuse to accept or acknowledge digital forms, necessitating a physical document that requires a signature by the signing authority. As such, thousands of individuals must drive every day to a regional office, hand in a form (to buy or sell land, for example) to be signed and transferred higher up the chain, collecting signatures at each stop, and then possibly going to the relevant ministry in Baghdad before finally being returned. This hangover of the centralized Ba’athist era must go if a decentralized model of federalism in Iraq is to move forward, and timely services are to be provided anywhere.42

Political impediments

Part of the reason the decentralization process has been so slow and difficult is related to politics and power. The federal government fears that corrupt individuals will embezzle their cash and tribal matters will dictate what money is left and how it is spent. And this has been borne out: as administrative authorities came to the governorates, PC members took advantage of operational budget costing and strong-armed local DGs to hire their preferred candidates through wasta — the Arabic term for having/utilizing “connections,” generally to further political or individual interests — or risk losing their jobs, having family members denied access to jobs and services, or facing intimidation and threats.43 However, from the governorate perspective, this problem of corruption and patronage networks is already rampant in the federal government. Furthermore, as discussed in the previous section, the governorates feel that they are set up for failure by the federal ministries with improper delegation of authorities and finances.

Additionally, provincial and national politics have deep overlap in which the provinces face political interference aimed at exercising control over their resources or land. For example, in Ninewa, parties such as the Kurdish Democratic Party, Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, al-Hal, and others reached out to, coerced, and bribed members of the PC to elect someone favorable to their interests as governor.44 Such examples make further fiscal empowerment look less and less appealing.

These issues are compounded by conspiracy theories, corruption, and infighting, like when the ex-governor of Mosul, Atheel al-Nujaifi, told Dijlah TV on June 9, 2019 that Iraqi security forces handed Mosul over to ISIS so that they could take the city back and further “Iranian infiltration” in Iraq. In other cases, the governor of Diyala reportedly stole millions allocated to refugees in 201545 and the previous governor of Ninewa, Nawful Akoub, allegedly stole $60 million from the public purse after he left office as a result of the Mosul ferry disaster.46 Behavior like this among local governorates does not inspire trust on the part of the federal government. As there have not been governorate elections since 2013, local politics has become increasingly individualized with ad hoc attempts to unseat governors and empower an executive more aligned with PC majority interests.

This is also an issue in the governorates: in rural, agricultural Diwaniyah, the directorate that focuses on land claims for farming recommended that some authorities remain in Baghdad, as it insulates their actions from PC and tribal interference should there be a tribal clash. However, the directorate also noted that they are far better suited to provide services: they are local, have a much deeper knowledge of associated tribal dynamics, and can provide a more proficient response than their counterparts in Baghdad.

Law 21 also allows the governorates to decide where Iraqi military units are stationed locally. As questions circle around the future role of the PMF, issues continue to emerge regarding oil smuggling by certain PMF units47 and the purchasing of land and businesses in the governorates.48 Other cases circle around the ability to appoint police chiefs, as highlighted when former Prime Minister Abadi moved to replace the Basra police chief in 2018, resulting in an uproar between the governorate and the federal government.49 Additionally, Law 21 allows for the governorate to decide who sits on its judiciary, creating fears about further corruption. However, as this is already a problem, the concern is that decentralization would only make things worse.

Lastly, most PCs are deeply unpopular, and there has been discussion of simply removing them due to their corruption and politicking.50 While it will be a very difficult task, there must be further efforts to address corruption among the PCs and install firewalls to split the executive and legislative branches of the governorates. A necessary first step would be to hold elections, since the last such polls were held in 2013 and have been postponed beyond their previously scheduled date of 2017. While the federal government adopted the Sainte-Laguë method — an electoral method to allocate seats in a party-list proportional system — in response to the 2010 ruling, national party disputes around the law to make it benefit them strategically in the governorates lead to continuing controversy.51 As of July 24th, 2019, the Iraqi parliament amended the provincial election law again, reducing the total number of seats and adapting the law with a measure that benefits larger parties (and thus status-quo parties).52 This relates back to the overlap between federal and governorate politics. The current estimated date for elections is April 2020.

Where is Iraqi federalism going?

Despite these problems, both sides know that the status quo cannot continue, but are currently working against entrenched personal and political interests. For example, one governorate-level director in charge of decentralized water services was called by hospitals warning that unless their water services are delivered on time, they would have to turn to local militias. Meanwhile, many of these same directors are unable to provide a plan on things such as water sterilization and purification due to the lack of an investment budget, which is still withheld by the federal ministry. This situation can lead to major political fights, such as when the governor of Basra, Asaad al-Eidani, and former Prime Minister Abadi got into a verbal altercation in Parliament over the Basra water crisis during the summer of 2018. Eidani made a fair point where he said the federal government did not send adequate, timely funding, and that parts of the water infrastructure project were held up at the border (which is manned by federal police) due to demands for bribes. At the same time, party corruption, tribal threats, and extortion hindered the project to the point of failure.53 As the World Bank reported in 2016, “The Iraqi public administration system, as it pertains to the municipal, water and sanitation sector, does not allow for any autonomy in decision-making at the subnational level.”54

It is from here that the recent talk of an independent Basra region has sprung up in the last few months.55 This idea has come up several times in the past but to no effect — from Abdul Aziz-Hakim’s 2005 speech56 to Wael Abdel-Latif al-Fadel in 2008,57 2011/12,58 59 2014,60 and then 2018/2019 by Eidani. This is not, by any standards, a new occurrence; what is interesting about it is that it appears to be driven by the demands of the PC members, rather than by the public, as the conditions that drove the protests in the summer of 2018 — poor services — have not improved.61

Overall, Iraq is slowly proceeding with decentralization. At times the progress of decentralization has been dependent on the personality of the minister in question: recently, the new minister of construction, housing, municipalities, and public works, Bangin Rekani, decentralized numerous authorities62 after becoming frustrated with the sheer number of files that were sent up for his personal signature, many of which had been inherited from his predecessor, and this ultimately led to many of the files being resolved. However, in other ministries, this change has yet to occur.

Furthermore, on the issue of subsidiarity, there are discussions around the further empowerment at the Qada and Nahiyah (district and sub-district) levels — this is featured both in the governorates not incorporated into a region and in the KRG — as well as further empowerment of Qaim al-Qam (district administrators). The idea is that the Qada and Nahiyah, which provide most of the day-to-day services and datasets that feed into service provision at the governorate level, would be better positioned to carry out their tasks. Additionally, this would also help to benefit returnees as neighborhood Mukhtars (heads) can work more closely and quickly with relevant officials to safely return citizens to their homes. This falls in line with the goal of functional federalism in Iraq. Still, the structures and capacity of these sub-levels are very limited and they would need to have the opportunity and support to grow and strengthen in time.

On the legal front, the Iraqi parliament adopted a new Financial Management Law, replacing the Coalition Provisional Authority Order from 2004. This new law is designed to better adapt the Iraqi financial management structure to a federal model. This is a step in the right direction, and governorates are delivering training to adapt their budgetary processes, update skills, and better prepare revenues.63 All the same, many of the ministries have been more keen to decentralize specific administrative components of their organizations, while retaining personnel and authorities related to finances, inhibiting the governorate directorates' ability to develop and execute on services.

Nonetheless, the governorates are seeing real gains in their ability to take on further responsibilities and develop the appropriate budgeting standards to execute on those authorities. This is a real win for Iraqis. The progress should be lauded and the process continued. A common concern is that the governorates cannot execute a budget as large and complex as one that would come from total decentralization. While this is correct for the most part, programmatic training of governorate staff via learning by doing has led to a positive change in budgeting standards and consolidation in Diwaniyah and Maysan. This is a big jump for the governorates: developing the skills and processes necessary for them to develop a realistic and executable budget that is accepted by the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Finance will represent a positive change in the ability to deliver services.

Overall, two necessary conditions must be met to be able to fully drive the decentralization process: 1) the support, growth, and diversification of revenues in both the federal government and governorates to better support investment budgets, and 2) the political acceptance of a decentralized state. Both of these factors are significant and very difficult to meet, and as always are far more complicated than just saying them and willing them into reality. As an example, Iraqi Finance Minister Fuad Hussein met with the governor of Wasit, Mohammed Almayahi, to discuss the governorate’s budget and the federal provisional allocations to cover lecturers and contract employees.64 He also met with Fares Siddiq, an MP from Ninewa, to discuss the financial allocations necessary for Ninewa.65 This suggests the continuation of the top-down, centralized approach through which the Ministry of Finance operates, and the continued ad-hoc budgetary process that the governorates face. On the other hand, it is the first time in six years that the Ministry of Finance has reached out to the governorates to discuss the operational budgets, showing at least a potential restart of intergovernmental dialogue. There is also a task force on reforming the financial sector and Ministry of Finance, focused on developing decentralized program budgeting, and away from itemized budgeting. These signs are hopeful but have yet to result in concrete action;66 nevertheless, the will is there.

Iraq is in the middle of a process of decentralized federalism, a process that takes years or even decades to settle. Federalism as a concept is a process that never ends, as the state evolves and adapts to new political and economic realities. Looking at the history of Iraq, the state has undergone a radical shift from full centralization to partial decentralization, a process that began 14 years ago and is still ongoing. While some argue that the process is slow, it takes a significant amount of time to change a single institution, let alone a full governance model. This is not to excuse the abuses of certain political actors in Iraq, but rather to explain how and why things are what they are. While the current state of play cannot continue, there has been tangible success in different areas, as discussed previously. Additionally, new technologies like the smart debit Qi Card have helped to make payment systems easier and more accessible for government staff. What needs to happen now is for the Iraqi government to embrace and support positive change and, more importantly, for citizens to see and feel those successes.67 Until that happens, Iraqis will continue to feel frustrated with their government. Gains in decentralization, though, should not be ignored, but encouraged. Focusing on problem areas is necessary, but implementing solutions and celebrating successes is the path forward if the problems discussed are to be resolved.

At the end of the day, services in Iraq must improve, and federalism is one pathway to get there — and one that can be a very strong tool to improve Iraqi governance. While significant hurdles exist, as Ali Mawlawi of the Bayan Institute puts it, “policymakers should not lose sight of the end goal. If Iraq is to emerge from decades of conflict and create the conditions for a sustainable peace, it needs to first rebuild trust between citizens and state by demonstrating efficient and effective governance. The extent to which federalism is functioning in Iraq should be measured against this standard.”68 There is a meaningful way to achieve a functional decentralized model of federalism in Iraq to improve the lives of everyday Iraqis, and there are many within the Iraqi public service who are able and willing to accomplish this task. However, they must be empowered with the right authorities, training, and processes to do so. Otherwise, they are set up for failure, and the citizen suffers the consequences. With climate conditions only getting worse, timely action is desperately needed to resolve the management of critical resources such as water, which has governance implications across nearly every aspect of government and life.69

Politicians in Iraq would be wise to realize that the status quo cannot continue; change is not only needed, but it is the only option left if the state is to thrive.

Endnotes

1. Law 21 (2008) of the Provinces not Incorporated into a Region. For the sake of brevity, it will be referred to as Law 21.

2. MERI, “MERI Forum 2018, P1: Decentralisation and Institutionalisation,” http://www.meri-k.org/multimedia/panel-1-of-meri-forum-2018/. November 25, 2018.

3. Lukman Faily, “Functional Federalism: Federal Regions, Governorates, and Good Governance,” 1001 Iraqi Thoughts, http://1001iraqithoughts.com/2018/05/09/functional-federalism-federal-regions-governorates-and-good-governance/. May 9, 2018.

4. Sean Kane, Joost Hiltermann, Raad Alkadiri, “Iraq’s Federalism Quandary,” The National Interest, https://nationalinterest.org/article/iraqs-federalism-quandary-6512. February 28, 2012. ; Robert Guiu, “Baghdad-Erbil Agreement on Oil and Budget: Deepening Iraq’s Federalism?” MERI, http://www.meri-k.org/baghdad-erbil-agreement-on-oil-and-budget-deepening-iraqs-federalism/. December 9, 2014.

5. There are many notable exceptions of course; most recent being Ali Mawlawi, “Exploring the Rationale for Decentralization in Iraq and its Constraints,” Arab Reform Initiative, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/exploring-the-rationale-for-decentralization-in-iraq-and-its-constraints/. July 31, 2019. The MERI Forum in 2018 also featured a discussion on the matter: MERI, “MERI Forum 2018, P1: Decentralisation and Institutionalisation,” http://www.meri-k.org/multimedia/panel-1-of-meri-forum-2018/. November 25, 2018.

6. Iraq still lacks a federal oil law. While one has been drafted, it has yet to be passed in Parliament. This is another major issue concerning Iraqi fiscal federalism, but deserves its own dedicated paper, and is out of scope for this current piece.

7. For an extensive review on the evolution of government budgeting in Iraq, see James D. Savage, Reconstructing Iraq’s Budgetary Institutions: Coalition State Building after Saddam, Cambridge University Press: New York. 2013.

8. Ibid, p.219.

9. Ibid, p.223.

10. Ahmed Tabaqchali, “Iraq’s Investment Spending Deficit: An Analysis of Chronic Failures,” AUIS. December 2018. P.7.

11. Munquth Dagher, “100 Days of Adel Abd Al-Mahdi’s Government,” IIASS, https://iiacss.org/100-days-of-adel-abd-al-mehdis-government/. March 1, 2019.

12. Muhanad Mohammed, “Iraq PM sets 100 day deadline for gov after protests,” Reuters, https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFTRE71Q1XI20110227. February 27, 2011. ; Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, “Protests are mounting in Iraq. Why?”, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/07/21/protests-are-mounting-in-iraq-why/?utm_term=.d6ea36d15784. July 21, 2018.

13. Alex Danilovich, “Federalism and Kurdistan Region’s Diplomacy.” In Alex Danilovich (ed.) Iraqi Federalism and the Kurds: Learning to Live Together (pp.87-112) (Farnham, Surrey, Great Britain: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2014).

14. Namely, the federal ministries of Health and Environment, Education, Municipalities, Labor and Social Affairs, Agriculture, and Youth and Sports. The Administrative and Financial Affairs Directorate was established to be a somewhat nascent Ministry of Finance, while the Provincial Planning and Development Council (PPDC) is an arm of the Ministry of Planning.

15. Thank you to Inna Rudolph for pointing this out to me.

16. The latest amendment retracted Health and Education from being decentralized, but this occurred halfway through the decentralization process, creating legal and administrative confusion. This amendment has been viewed as not in favor of decentralization, and in fact hampering Law 21’s core objective.

17. Law of the Provinces not Incorporated into a Region, no.21 of 2008, as amended. Available in English from the Iraq Governance Strengthening Project (Taqadum), Chemonics, funded by USAID, May 2017. http://iraqgsp.org/provinces-not-incorporated-into-a-region-law-no-21-o….

18. Ibid, Article 45.

19. Hashim al-Rikabi, “Localizing Politics is the Way Forward in Iraq,” Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies, http://www.bayancenter.org/en/2019/03/1829/. February 2, 2019.

20. Ahmed Tabaqchali, “A Review of Iraq’s 2019 Budget Proposal,” 1001 Iraqi Thoughts. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MewEplR3NZ3RCNXe3Xe4pX9wNOSGnBZt/view. November 2018.

21. Non24,” وزير المالية يكشف اعداد موظفي الدولة قبل وبعد عام 2003,” Non24, http://non14.net/112793/. May 29, 2019.

22. Interviews with Iraqi government officials, July 2018 and February 2019.

23. Omar Sirri, “Reconsidering Space, Security, and Political Economy in Baghdad.” LSE Middle East Center Blog, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2019/08/12/reconsidering-space-security-and-political-economy-in-baghdad/. August 12, 2019.

24.Discussions from meetings in Baghdad, July 2018. Names withheld for privacy and security.

25. The Mosul Dam is one such example of infrastructure that has been neglected over time, but water sanitation plants and buildings for schools or even government also face degradation due to lack of funding for maintenance.

26. Iraq, Systematic Country Diagnostic Report No. 112333-IQ (figure’s 50 & 51 page: 65). Sources cited in report are Iraq Ministry of Finance (MoF), World Development Indicators, International Monetary Fund (IMF). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/542811487277729890/pdf/IRAQ-S…

27. Both tables from Ahmed Tabaqchali, “Iraq’s Investment Spending Deficit: An Analysis of Chronic Failures,” AUIS. December 2018. As noted on pages 4 and 6, data from “IMF Iraq Country Reports 13/217 and 17/251 for 2010-2012 (no breakdown figures for this period) and 2013-2017 respectively (2017 are projections); amendments to 2019 Budget Law dated 8 October 2018 for 2018-2019. Ministry of Finance (MoF) end of year reports for separate figures for 2015-2017, http://mof.gov.iq/obs/ar/Pages/obsDocuments.aspx.”

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid, p.6.

30. Table from World Bank, “Republic of Iraq – Decentralization and Subnational Service Delivery in Iraq: Status and Way Forward,” World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/583111468043159983/pdf/Iraq-Decentralization-JIT-Assessment-Report-March-2016-FINAL.pdf. March 2016. P. 75. Data from Iraqi Budget Execution Report, United Nations Joint Analysis.

31. Ibid. P.i.v.

32. Interviews with Iraqi Government sources, July 2018 and February 2019.

33. World Bank, “Republic of Iraq – Decentralization and Subnational Service Delivery in Iraq: Status and Way Forward,” World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/583111468043159983/pdf/Iraq-Decentralization-JIT-Assessment-Report-March-2016-FINAL.pdf. March 2016. P. iv.

34. Ibid. P.iv.

35. Table from Ibid. P.74. Data obtained from Ministry of Finance, Baghdad.

36. Thomas Doherty, “Tarabot Decentralization Consulting Unit: Progress and Prospects,” USAID. February 27, 2014. P.9.

37. Interview with Iraqi government official, February 2019.

38. Al Mirbad. “القضاء يحكم بارجاع كوشان مديرا لتربية الديوانية,” Al Mirbad. https://www.almirbad.com/detail/17870. June 30, 2019.

39. Ali Mawlawi, “Exploring the Rationale for Decentralization in Iraq and its Constraints,” Arab Reform Initiative, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/exploring-the-rationale-for-decentralization-in-iraq-and-its-constraints/. July 31, 2019.

40. Interviews with Iraqi government officials, July 2018 and January 2019.

41. Ibid.

42. Highlighting this example is a recent case where it took around 52 official letters between government offices (each requiring a signature) and 13 months to move a teacher from one branch to another, 7 months being unpaid (https://twitter.com/Hamzoz/status/1145451675676762112).

43. Interviews with Iraqi government officials, July 2018 and February 2019. In one case a director complained that he was being pressured to hire the chai-chi, or tea man, who had just served tea during interviews as a team lead in the directorate despite no experience or relevant education in the subject matter.

44. Al Mada, “البرلمان يعوّل على إقالة مجلس نينوى والتفرّد بالمرعيد رداً على تجاهله,” https://almadapaper.net/view.php?cat=218569. May 14, 2019.

45. Rudaw, “Diyala governor accused of stealing millions in refugee funding,” Rudaw, http://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/250320153. March 25, 2015.

46. MEMO, “Iraq: $60m of gov’t funds stolen from Mosul,” Middle East Monitor, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190423-iraq-60m-of-govt-funds-stolen-from-mosul/. April 23, 2019.

47. Mohammed Hussein, Samya Kullab, Rawaz Tahir, Ben Van Heuvelen, and Staff of Iraq Oil Report, “Kirkuk Oil Smuggling Rings Thrive Amidst Corruption,” Iraq Oil Report, https://www.iraqoilreport.com/news/kirkuk-oil-smuggling-rings-thrive-amidst-corruption-36558/. January 31, 2019. Notably, other groups such as Peshmerga units had also engaged in smuggling.

48. John Davidson, “Iraqi Shi’ite groups deepen control in strategic Sunni areas,” Reuters. https://reut.rs/2KgurBx. June 13, 2019.

49. Further details on this affair is featured in Ali Mawlawi, “Exploring the Rationale for Decentralization in Iraq and its Constraints,” Arab Reform Initiative, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/exploring-the-rationale-for-decentralization-in-iraq-and-its-constraints/. July 31, 2019.

50. By politicking I refer to PC interference in the executive of the governorate, personal claims on projects being completed, and reciprocal deals made between members and political parties on what projects are approved and who benefits. This is discussed in detail in the case of Basra in Zmkan Saleem and Mac Skelton’s “The Politics of Basra’s Unemployment Crisis: Spotlight on the Oil Sector” 2019, http://auis.edu.krd/iris/publications/politics-unemployment-basra-spotl….

51. Kirk Sowell, “Wrangling over Iraq’s Election Laws,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace – Sada. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/68730 . April 20th, 2017.

52. Baraa al-Shammari, “Sainte-Laguë to 1.9: The local elections law in Iraq and the exclusion of small parties.” The New Arab. July 23rd, 2019.

53. Omar Sattar, “Will Iraqi provincial councils’ be abolished?” Al-Monitor, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2018/11/iraq-provincial-elections.html. November 19, 2018 ; Zmkan Ali Saleem and Mac Skelton, “Basra’s Political Marketplace: Understanding Government Failure after the Protests,” IRIS Policy Brief, http://auis.edu.krd/iris/sites/default/files/Saleem%20and%20Skelton%20-%20Basra%27s%20Political%20Marketplace_0.pdf. April 2019.

54. World Bank, “Republic of Iraq – Decentralization and Subnational Service Delivery in Iraq: Status and Way Forward,” World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/583111468043159983/pdf/Iraq-D…. March 2016.

55. Omar Sattar, “Iraq’s Basra seeks to upgrade to federal region,” Al-Monitor, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/04/iraq-basra-region-federalism.html. April 26, 2019.

56. Reider Visser, “The Two Regions of Southern Iraq,” In Reider Visser and Gareth Stansfields (eds.) Iraq of its Regions: Cornerstones of a Federal Democracy? (pp.27-50) (London: Hurst Publishers Ltd., 2007).

57. Rania Abouzeid, “A New Twist in Iraq’s Shi’ite Power Struggle,” Time, http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1859465,00.html. November 16, 2008.

58. Of which also included calls for a region in Diyala and Salahaddin

59. Ahmad Wahid, “Iraq Turmoil Prompts Basra to Propose Southern Province,” Al-Monitor, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/politics/2012/05/basra-threatens-to-form-a-sout-1.html. May 31, 2012.

60. Shafaaq News, “IHEC: We are Technically Ready for a Referendum of Basra Region,” Shafaaq News, https://www.shafaaq.com/en/iraq-news/ihec-we-are-technically-ready-for-a-referendum-of-basra-region/. December 5, 2014.

61. Zmkan Ali Saleem and Mac Skelton, “Basra’s Political Marketplace: Understanding Government Failure after the Protests,” IRIS Policy Brief, http://auis.edu.krd/iris/sites/default/files/Saleem%20and%20Skelton%20-%20Basra%27s%20Political%20Marketplace_0.pdf. April 2019.

62. Such as sign-off authority and contracting, as well as the completion of the transfer of personnel to the Governorates.

63. Notably, much of this work is funded by international organizations. This has its own issues, which is out of the scope of this piece, but worth discussing on its own.

64. Of which provincial costs rose in the 2019 budget due to a provision to bump up contract employees to permanent, and daily to contract; Fuad Hussein, https://twitter.com/Fuad_Hussein1/status/1139195436697292800, Twitter. June 13, 2019.

65. Fuad Hussein, https://twitter.com/Fuad_Hussein1/status/1139154915060830209, Twitter. June 13, 2019.

66. Additionally, the World Bank is working on a project, “Modernization of Public Financial Management Systems Project,” of which a component is an Integrated Financial Management System (IFMS). However, much like the projects that came before it, the World Bank’s audits of the program have its listed of results as “Unsatisfactory” to “Moderately Unsatisfactory.” This is likely due to the ongoing difficulties and resistance of reform that the Ministries of Finance and Planning have consistently held. Only recent reports list the success of the program to moderately satisfactory. See http://projects.worldbank.org/P151357/?lang=en&tab=overview for details. Further discussion on the IFMS since 2005 is important, but lends itself better to another article.

67. There have indeed been real successes on different projects developed by different teams in directorates in the governorates. For example, in Diwaniyah a director had managed to completely change the garbage collection system in the city, making it more efficient and effective. While there are still significant problems and hurdles that could have been avoided, such as issues discussed earlier, this success is a case where continued support will lead to more change.

68. Ali Al-Mawlawi, “’Functional Federalism’ in Iraq: A Critical Perspective,” LSE Middle East Centre Blog, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2018/03/11/functioning-federalism-in-iraq-a-critical-perspective/. January 15, 2018.

69. Peter Harling, “Nature’s Insurgency: Water wanted in the land of plenty.” Synaps Network. http://www.synaps.network/natures-insurgency. August 5, 2019.

Photos

Main photo: Iraqis prepare to cross a checkpoint as they celebrate the re-opening of the Green Zone, home to government buildings and Western embassies, on December 10, 2018 in the capital, Baghdad. (Photo credit AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty Images)

Contents photo: Iraqis waiting to have their paperwork signed at a directorate in Diwaniyah. Much of the paperwork still requires official signatures on physical documents, as different ministries do not accept electronic copies. This results in slow approval on many day-to-day services as this paperwork often must be physically sent to Baghdad to the federal ministry for approval and then sent back to the governorate directorate. (Photo by the author)

First pull quote photo: A Kurdish MP stands outside Kurdistan's Parliament building in Erbil, the capital of the autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq on September 15, 2017. Iraqi Kurdish lawmakers approved holding an independence referendum on September 25 as members of the opposition boycotted the Parliament's first session in two years. (SAFIN HAMED/AFP/Getty Images)

Second pull quote photo: An Iraqi print house worker discusses the design of a campaign leaflet with a candidate's staff while they work the graphics on an office computer February 3, 2010 in Baghdad, Iraq. Print house workers have been laboring three shifts a day to keep up with demands for campaign posters as Iraq prepares for the upcoming March 7th national elections. (Scott Peterson/Getty Images)

Final photo: Iraqis who have fled the violence in Mosul attend a meeting with the provincial council of the southern port city of Basra, on July 28, 2014, during which they received presents and some amount of money for the first day of the Eid al-Fitr festival that marks the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. Sunni and Shiite religious officials have said on July 26 Islamic State (IS) militants had destroyed or damaged dozens of shrines and husseiniyas in and around Mosul since they overran part of the country six weeks ago. (HAIDAR MOHAMMED ALI/AFP/Getty Images)

About the author

Mike Fleet is a senior researcher at the Institute on Governance, where he works with the Iraq team and helps to implement the Fiscal Decentralization and Resiliency Project. Prior to joining the IOG, Mike worked with Global Affairs Canada as a junior policy analyst. He also held a junior research fellowship with an international think tank where he wrote policy recommendations for the Canadian government on China's Belt and Road Initiative. He completed a Master of Arts degree in Global Governance from the Balsillie School of International Affairs at the University of Waterloo, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Memorial University of Newfoundland

About the Middle East Institute

The Middle East Institute is a center of knowledge dedicated to narrowing divides between the peoples of the Middle East and the United States. With over 70 years’ experience, MEI has established itself as a credible, non-partisan source of insight and policy analysis on all matters concerning the Middle East. MEI is distinguished by its holistic approach to the region and its deep understanding of the Middle East’s political, economic and cultural contexts. Through the collaborative work of its three centers — Policy & Research, Arts & Culture and Education — MEI provides current and future leaders with the resources necessary to build a future of mutual understanding.