Summary

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, Saudi Arabia has been concerned about the potential influence of Iran’s supreme leader among its Shi’a population, which comprises around 10-15% of the majority-Sunni country, especially since Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei took on the title of Vali-ye faqih, or “guardian-jurist.” Such concern is understandable given that the two countries are both neighbors and rivals: Khamenei is a marj’a, the highest-ranking Shi’a religious authority, but he is also the commander-in-chief of the Iranian Armed Forces. This concern over Iranian influence among the Saudi Shi’a community reached its peak following the Khobar Towers bombing on June 25, 1996, a terrorist attack that targeted members of the United States Air Force’s 4404th Wing (Provisional) stationed in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, home to much of the kingdom’s Shi’a population. This paper aims to investigate the Iranian influence within the Shi’a community in Saudi Arabia by focusing on the followers of the supreme leader’s marj’aiyyah, known as “Khat al-Imam,” and its military wing, “Hezbollah Al-Hejaz,” also known as “Saudi Hezbollah,” often held responsible for carrying out the 1996 attack.

Introduction

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, Saudi Arabia has been concerned about the potential influence of Iran’s supreme leader among its Shi’a population, which comprises around 10-15% of the majority-Sunni country, especially since Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei took on the title of Vali-ye faqih, or “guardian-jurist.” Such concern is understandable given that the two countries are both neighbors and rivals: Khamenei is a marj’a, the highest-ranking Shi’a religious authority, but he is also the commander-in-chief of the Iranian Armed Forces. This concern over Iranian influence among the Saudi Shi’a community reached its peak following the Khobar Towers bombing on June 25, 1996, a terrorist attack that targeted members of the United States Air Force’s 4404th Wing (Provisional) stationed in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, home to much of the kingdom’s Shi’a population.

This paper aims to investigate the Iranian influence within the Shi’a community in Saudi Arabia by focusing on the followers of the supreme leader’s marj’aiyyah, known as “Khat al-Imam,” and its military wing, “Hezbollah Al-Hejaz,” also known as “Saudi Hezbollah,” often held responsible for carrying out the 1996 attack. The major challenge in exploring this topic is that there are no solid references for most of what has been written about the group. Indeed, the majority of what is attributed to Saudis who espouse Vali-ye faqih comes from their Shi’a rivals, which casts doubts on the credibility of the claims. This paper clarifies the underlying accounts about the group that have been cited by subsequent scholars and journalists in their own narratives.

Khomeini, Khamenei, and Vali-ye Faqih

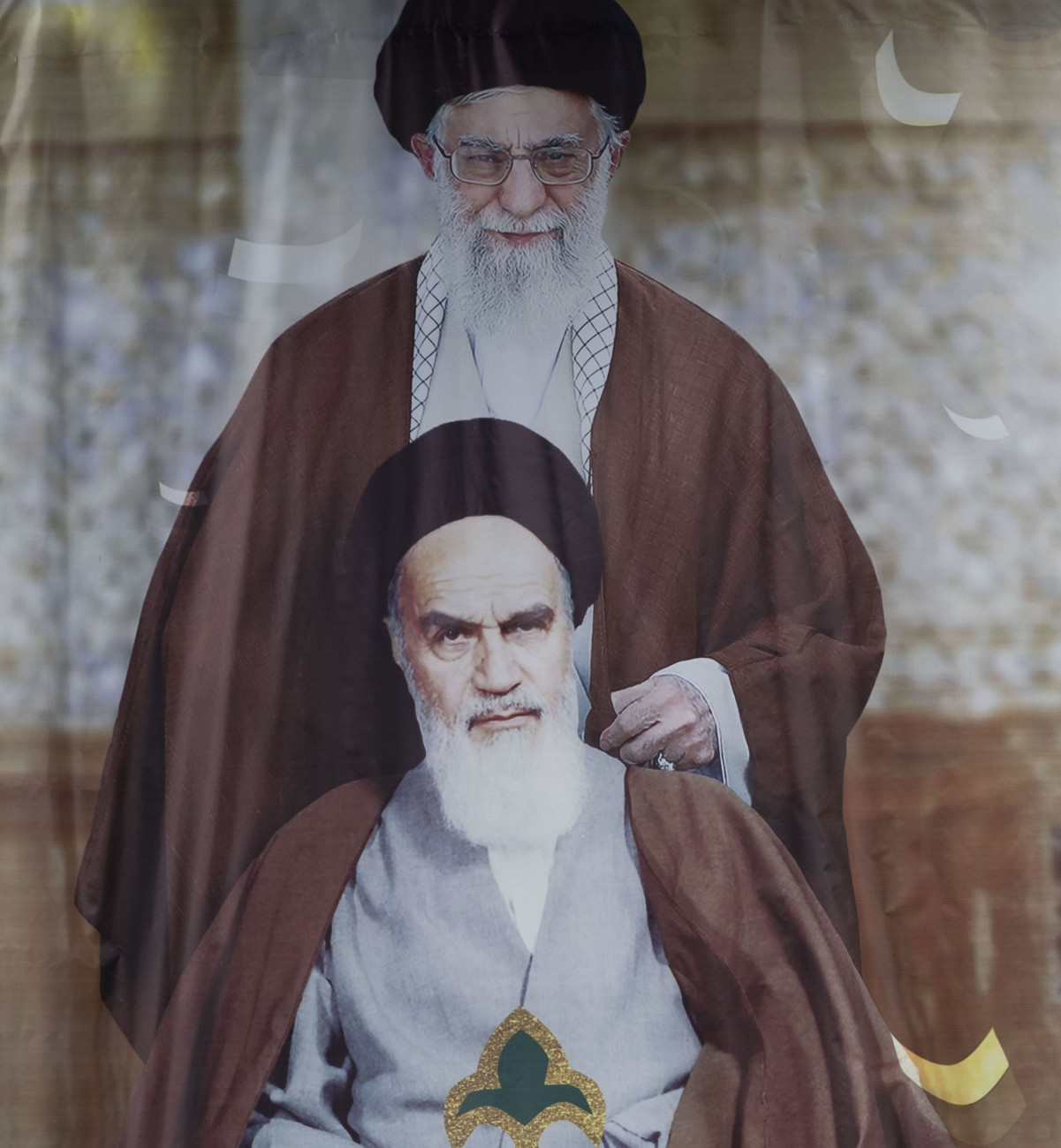

Since Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini (d 1989) came to power as the supreme leader of Iran following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, there has been a major ongoing debate over the role of ayatollahs in the political sphere in the Middle East. Khomeini influenced many Islamic activists worldwide, especially Shi’a armed groups in Lebanon and Iraq, who considered him to be the marj’a with the right to make decisions within the confines of shari’a law. Since 1989, Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Khamenei, has legitimized his rule by taking on the position of Vali-ye faqih, which in theory means he serves as “the guardian of Muslims worldwide.” Despite the obvious doctrinal and geographic limitations, the belief in his transnational authority as a religious and political leader is a major concern for countries where some members of the Shi’a community follow him as the grand marj’a. Moving beyond Khomeini, Khamenei has expanded his control within Shi’a communities as a modern marj’a. “Through sophisticated mechanisms, he has altered the symbolic and material capacity of the Shiite religious institutions throughout the region in his own political favor, using them for his anti-Western and anti-American policy.”1

Khat al-Imam

The term “Ansar Khat al-Imam” originally referred to the Iranian students who stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in November 1979, but subsequently has been broadened to include all Shi’a activists who adopt the lessons and ideology of Khomeini.

Breaking down this term, the word ansar means “adherents” in Arabic, khat means “line” and is used to refer to any group advocating a specific ideology, while Imam refers to Ayatollah Khomeini, who is, unlike other marj’as, called Imam by his adherents. In Shi’a discourse, the term Imam is supposed to be used exclusively for the Twelve Imams, who are infallible. There are very few exceptions where the title is used for clergy, of which Khomeini is most important. Thus, the term Khat al-Imam means “the line or followers of Khomeini” — and of course, of his successor Khamenei. This term conveys loyalty to the Iranian supreme leader as an individual who enjoys the absolute guardianship of the ummah, or Muslim community, but this is not necessarily limited to the Iranian government. However, it is difficult to separate the head of a state from his government.

When Ayatollah Khomeini was living in exile in Najaf, Iraq (1965-78), some young Saudi clergy met him and were inspired by his charisma. In 1972, Sayyid Hashem bin Muhammad al-Shakhs moved from al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province to Najaf to join the seminary there. He attended Khomeini’s lessons and gradually decided to take a different path from his family, who traditionally followed the major marj’aiyyah in Najaf. Instead of following the marj’aiyyah of Sayyid Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei (d 1992), al-Shakhs adopted Khomeini’s. At that time, Khomeini was a spiritual leader who was lecturing about the ideal Islamic government with a primary focus on Iran. He was not a popular marj’a compared to al-Khoei in Najaf or Sayyid Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari (d 1986) in Qom, Iran, and his new followers from al-Ahsa attracted little attention at the time, as they had no political ambitions.

During the 1970s, a number of Saudi theological students in Najaf, mainly from al-Ahsa, attended the lessons of Sayyid Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (d 1980), a young marj’a who was very close to Khomeini in terms of his theocratic views. These young students were influenced by al-Sadr’s intellectual discourse, which went beyond the traditional teaching of Shi’a seminaries in theology and jurisprudence to incorporate modern philosophy, economics, and politics. Al-Sadr was the marj’a followed by the founders and adherents of the Islamic Dawa Party, which was banned by Iraq’s Ba’ath regime. The most prominent of those students who engaged in work with the Dawa Party was Sheikh Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli (d 2013), the late chair of the Department of Arabic Language and Literature at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. After the success of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, many of al-Sadr’s students moved to Qom to escape oppression by the Iraqi authorities, especially after al-Sadr was arrested and executed in April 1980.2 They started to attend the lessons of Ayatollahs Sayyid Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi (d 2018) and Sheikh Hussein Montazeri (d 2009), who was the designated successor of Khomeini before he was removed prior to the latter’s death in 1989. It is worth noting that Montazeri is the author of the most important five-volume encyclopedia on Velayat-e faqih. Shahroudi was the chief of the Iranian judiciary for a decade, from 1999-2009, and used to be seen as a potential successor to Khamenei as supreme leader.3

In 1987, in the seminary of Qom, a number of Saudi Shi’a clergy who used to attend al-Sadr’s lessons in Najaf before moving to Iran created a group called Tajam’u ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz (the Ingathering of Hejazi Clergy) and started their own seminary. Hejaz is the historical name of the western part of the Arabian Peninsula; they used it to indicate that they did not recognize the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as a national entity. Their choice was also aimed at differentiating themselves from the other Shi’a opposition group that followed the marj’aiyyah of Sayyid Muhammad Shirazi (d 2001), which had already picked the name munazzamat al-Thawra al-Islamiyya fi al-jazira al-‘Arabiyya (Islamic Revolution Organization in the Arabian Peninsula, or IRO). The Shirazis and the IRO were the most recognized Shi’a opposition group active during the 1980s, before they benefited from a royal pardon issued by King Fahd in 1993 to all Shi’a dissidents abroad.4 Accordingly, the new pro-Khomeini group chose to use the name of the region that is home to the major holy cities, Mecca and Medina, instead of one referring to the Arabian Peninsula. Thus, the Saudi Shi’a opposition known as Jaziraiun or Jaziraieen are the followers of Shirazi, while Hijaziun or Hijazieen are the followers of Khomeini and Khamenei.

The majority of the Saudi Shi’a who adopted Khomeini’s marj’aiyyah in 1980s were from al-Ahsa, such as Hashem al-Shakhs and Sheikh Hussain al-Radhi. The only known student from Qatif who attended Khomeini’s lessons in Najaf was Sheikh Abdul Jalil bin Marhoon al-Ma’a. Later, in Qom, a few Qatifi young clergy joined the group of Saudi adherents of Khomeini’s marj’aiyyah, such as Sheikh Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl and Sheikh Said al-Bahar. Unlike the Shirazi line, Khat al-Imam is more popular in al-Ahsa than Qatif. The reason for this might be that the clergy who attended Khomeini and al-Sadr’s lessons in Najaf during the 1970s were members of al-Ahsa’s noble families, as the social paradigm in al-Ahsa is more organized and solid than in Qatif. Thus, it is typical for most members of the same extended family — which could number in the thousands — to follow the same marj’a. In Qatif, most of the followers of Khat al-Imam were from two specific villages, al-Rabia‘iya (Tarut) and al-Jaroudiya.

Those clergy were focusing on religious teaching and promoting Khomeini’s marj’aiyyah among the Saudi Shi’a community. They were apolitical, and indeed, “had not taken part of the intifada [uprising] that was the key founding event of shirazi movement.”5

While the number of followers that each marj’a has is unclear, observers can come up with some estimates of the rough size of the various divisions within the Shi’a community. In Saudi Arabia, Khomeini had far fewer followers than other figures like al-Khoei (d 1992) or even Shirazi (d 2001). However, some of al-Khoei’s followers were supporters of Khomeini. After he passed away in 1989 and Khamenei succeeded him as supreme leader, Khamenei did not initially present himself as a marj’a. Tehran supported the marj’aiyyah of Sayyid Mohammad-Reza Golpaygani (d 1993) and then Sheikh Muhammad Ali Araki (d 1994). After that, Khamenei declared himself as a marj’a and brought the marj’aiyyah back to the Vali-ye faqih. Since then, a considerable number of Saudi Shi’a started to follow him as their marj’a, the majority of whom were born in the late 1970s. Indeed, it was a trend to follow Khamenei in the mid-1990s, as youth who were not interested in the traditional marj’aiyyah had no other choice after the Shirazis abolished their political opposition and returned to the kingdom after being granted a royal pardon.

It is no surprise to find apolitical Shi’a following Khat al-Imam. There is an important aspect of Khomeini’s character, the Irfan, which is a sort of Islamic mysticism, but mostly emphasized in Shi’a teaching. The Shi’a who are inspired by Khomeini’s Irfan might not be interested in his political role. Indeed, they would consider his political and military actions to be a consequence of his exceptional ability to deal with the materialistic world. This attitude is supported by certain stories of Iranian victories against their enemies, especially the U.S. and its allies. One example is Operation Eagle Claw, when President Jimmy Carter ordered the United States Armed Forces to penetrate Iranian territory to rescue the U.S. Embassy staff held captive in Tehran. The military operation, which took place on April 24, 1980, failed for multiple reasons, including unexpected bad weather in the Tabas Desert. The U.S. lost three out of eight helicopters that were sent on the mission.6 This story is used in Iranian propaganda as a sign of God’s blessing of Khomeini and the revolution, and it and other similar examples supported Khomeini’s spiritual aspect. There are also other stories about Khomeini and Khamenei, as well as the ayatollahs who supported the revolution, such as Sheikh Mohammad-Taqi Bahjat Foumani (d 2009) and Sheikh Abdollah Javadi-Amoli.

Hezbollah Al-Hejaz

The name “Hezbollah” recalls the armed groups that adopted Khomeini’s ideology, such as Lebanese Hezbollah and the Iraqi militias, especially Kata’ib Hezbollah. In general, very little is known about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz itself, including who their members are or which agencies they work with on a regular basis. The available information is limited and mostly consists of the names of individuals who were accused of involvement in violent attacks with a strong suspicion of an association with the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). This hypothesis is reasonable, since the IRGC is the Iranian agency that works with all of Tehran’s associated militias worldwide.7

As with most details about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz, the date of its founding is unclear. According to Toby Matthiesen, “Hezbollah Al-Hejaz was founded in May 1987. One week after the hajj incident it vowed to fight the Saudi ruling family.”8 The 1987 Mecca incident occurred on July 31 — when more than 400 people were killed following violent clashes between Iranian Shi’a pilgrims and Saudi security forces — and the threatening statement was issued that August. It was the first statement attributed to the organization, and during that three-month period between May and August there was nothing to prompt an escalation against the Saudi government.

The 1987 Mecca incident represents a turning point in tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia.9 Until then, the Iranians did not have reliable adherents inside Saudi Arabia. The Shirazis promoted propaganda against the Saudi government and the royal family. Despite the military training camps the IRO was running in Tehran, the Shirazis were not seriously interested in carrying out military operations, as they were aware of the consequences. By contrast, the Iranians understood that it best served their interests to keep such propaganda active, even if the Shirazis could not do more than just media work. In addition, the Shirazis lost an important ally in the Iranian government, Mehdi Hashemi, the head of the Office of Liberation Movements, the agency responsible for supporting organizations like the IRO. The Iranian authorities accused him of leaking details about the Iran-Contra Affair in late 1986. Hashemi was subsequently executed in 1987 and the Office of Liberation Movements closed.10

The identity of the Saudi founders of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz is also uncertain. The only known names are those already involved in or accused of participating in military operations on Saudi territory. The most recognized names were originally part of the Shirazis before shifting their ideology toward Vali-ye faqih. The most important name is Ahmad al-Mughasal, who became the leader of the military wing of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz. Al-Mughasal decided to leave the IRO because he did not find its ideology and actions revolutionary enough.11 Another former member of the IRO who joined Hezbollah Al-Hejaz was Khalid al-Ulq, one of the four members of a Hezbollah cell accused of bombing the SADAF petrochemical plant in Jubail in March 1988; al-Ulq and his companions were later executed that September.

There are multiple pieces that refer to either Hezbollah Al-Hejaz or Saudi Hezbollah. However, the picture is still blurry, as the literature offers little in the way of detail. Indeed, most of what has been written on this topic was based on their rivals’ narratives — that is, the former members of the IRO. The major original reference about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz was written by Fouad Ibrahim, a former member of the IRO, who wrote a book entitled The Shi‘is of Saudi Arabia (2006). Toby Matthiesen built on Ibrahim’s story and wrote a number of pieces about Shi’a in the Gulf. In 2010, he published an article entitled “Hizbullah al-Hijaz: A History of The Most Radical Saudi Shi‘a Opposition Group,” followed by a book four years later, The Other Saudis. The argument in both cases was built on Ibrahim’s narrative, supported by interviews — conducted by Matthiesen — with former members of the IRO. Most later scholars and journalists built their narratives on Matthiesen’s work. Thus, it is no surprise to find that most of what has been written about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz only touches on it in passing, as a group on the sidelines of the Shirazis and the IRO, rather than investigating the essence of the organization and Khat al-Imam.

Today, Matthiesen is considered the essential reference on Shi’a political history in Saudi Arabia. Researchers and journalists who write on the topic base their work on his narrative and accept it at face value. He, in turn, accepted the Shirazis’ narrative at face value. That is to say, the Shirazis are, in effect, passing on their narrative about their rivals through a Western scholar. For example, in his article “Iran and Hizbullah: A Very Special Relationship,” Muhammad Fawzy based his whole argument about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz on Matthiesen’s narrative.12

There is even a book (in Arabic) entitled Hezbollah al-Hejaz: Bedayat wa Nehayat Tanzeem Irhabi (Hezbollah al-Hejaz: Beginning and End of a Terrorist Organization). Hamad al-Issa, who presented himself as its translator, referred to Matthiesen’s 2010 article as the original work translated. Despite the mistranslation of the title, which changed “radical” to “terrorist,” the book prepared by al-Issa is 190 pages long, while Matthiesen’s article is only 18 pages.

Another sign that researchers have taken Matthiesen at face value is that most of the Arab writers simply copied-and-pasted from his work without even checking basic facts like names. For example, many Arabic books and articles referred to Sheikh Abdul Jalil al-Ma’a, a leader in Khat al-Imam, by the transcription of the name, which makes the last name (al-Ma’a) sound very strange, as there is no such family in Qatif. None of these Arab writers tried to find the right full name, which is Sheikh Abdul Jalil bin Marhoon al-Ma’a (al-Ma’a pronounced just like the word “water” in Arabic). Marhoon al-Ma’a is a family in Tarut, Qatif and people there omit the first part of it (Marhoon), as there are other families that use al-Marhoon as their last name.

Early Activities

Hezbollah Al-Hejaz was founded in 1987 at a time when tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia reached their peak. On August 16 of that year, an explosion occurred at one of ARAMCO’s petroleum facilities in Ra’s al-Ju’ayma (32 km north of Qatif). Another two attacks took place in March 1988, one at a SADAF petrochemical facility in Jubail (75 km north of Qatif) and the other at the Ra’s Tanura refinery (27 km north of Qatif), for which a “new group called hizbullah [sic] claimed responsibility.”13 These attacks followed several clashes with Hezbollah Al-Hejaz’s fighters that resulted in their arrest, along with the killing and injury of several Saudi policemen.

The four members of the cell accused of carrying out the SADAF attack were executed. In addition, a number of suspected followers of Khat al-Imam were arrested and later released after a royal pardon was issued for Shi’a prisoners, as a part of a deal with the Harakat al-Islahiyah (the Reform Movement), the new name of the IRO after it abandoned its revolutionary ideology, the members of which returned to the kingdom in 1993.

Hezbollah Al-Hejaz was not the only secret Saudi pro-Iranian organization that claimed to carry out attacks in Middle East. In the late 1980s, there was a series of assassinations of Saudi diplomats in Ankara, Bangkok, and Karachi claimed by two organizations, Jund al-Haqq (Soldiers of the Right) and Munazzamat al-Jihad al-Islami fi al-Hijaz (Islamic Jihad Organization in Hejaz).14 There are no details about those organizations beyond their statements claiming responsibility for the attacks and saying they were based in Beirut.

Some researchers such as Joshua Teitelbaum15 and Matthiesen16 see these organizations as part of the military wing of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz. Yet in the 1990s and after, they disappeared and they have never issued any other statements or claimed responsibility for any other operations, including the Khobar Towers bombing in 1996.

In the early 1990s, the tensions between the Saudi Shi’a community and their government seemed quiet. After Ayatollah Khamenei declared his marj’aiyyah, many young Shi’a espoused his marj’aiyyah as part of adopting Islamism within the Shi’a community.

The context at that time is critical, as many Sunni fanatics were confronting the Saudi government, blaming it for receiving assistance from Western forces to liberate Kuwait and letting them remain on Saudi soil afterwards. These Western forces had a strategic mission in the Gulf region that was beyond the narrow minds of those fanatics, who were focused on what they considered to be unjustified soft attitudes toward secular individuals and Shi’a. Sheikhs such as Safar al-Hawali, Salman al-Ouda, and Nasser al-Omar were the leading fanatical Sunni clergy at that time.17 This context created the best chance for Iranian intelligence to search for adherents to serve its agenda.

On June 25, 1996, the major terrorist attack in Khobar brought tensions between the Saudi Shi’a community and their government to a head, as the discourse that they were “followers of Iran” was promoted in the local media.

Khobar Towers Bombing

The Khobar Towers complex, located in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province (50 km south of Qatif), hosted 2,000 U.S. military staff assigned to King Abdulaziz Air Base in Khobar city. Building 131 was a housing complex for members of the U.S. Air Force assigned to Operation Southern Watch, tasked with enforcing the no-fly zone in southern Iraq.

On June 25, sometime between 9:30 and 10:00 pm, Sgt. Alfredo R. Guerrero and Airman Christopher T. Wagar were standing on the roof of Building 131. They noticed a white four-door Chevrolet Caprice driving through the parking lot, with another vehicle slowly following. It was a Mercedes-Benz fuel truck with a capacity of 3,500-4,000 gallons. Two men got out of the tanker truck, ran to the white Caprice, and left. At this point, Guerrero and Wagar were certain the tanker truck was a bomb. Not far from Building 131, Senior Airman Craig J. Dick was patrolling in a military vehicle when he heard a security alert on his radio and sped to the scene. He pulled up near the building, joined Guerrero and Wagar, and the three security policemen began evacuating the top two floors of Building 131.18

Their swift action and effort to evacuate the building did not entirely prevent casualties, however. While the three security policemen were able to begin evacuating the building, the explosion occurred just three minutes later, before the evacuation could be completed. The result was 19 killed (all Americans) and 498 of different nationalities wounded. It was the bloodiest attack targeting U.S. forces since the Beirut Marine barracks bombing in 1983.19

The presence of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Persian Gulf was a concern for both Iran and al-Qaeda. For legal and diplomatic reasons, Iran had very limited ability to express its displeasure. Al-Qaeda, as a terrorist organization, had made its attitude toward the American presence in the “Land of the Two Holy Mosques” clear, however. A few months earlier, on November 13, 1995, it carried out an attack against a U.S.-operated National Guard Training Center in Riyadh. Five Americans and two Indians were killed, while 60 people of different nationalities were wounded. Shortly thereafter, the Saudi authorities arrested and executed the four Saudi individuals who carried out the attack. The cell members appeared on national TV and acknowledged that they were inspired by Osama bin Laden.20

Given the account of the last attack by al-Qaeda in Riyadh, fingers were initially pointed at the transnational radical Sunni organization. Shortly thereafter, however, the focus turned toward radical Shi’a inspired by Iran, namely Hezbollah Al-Hejaz. The first indication of the involvement of the Saudi Shi’a group and Iran was during a meeting between Louis J. Freeh, director of the FBI, and Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador to the U.S., at the prince’s residency in McLean, Virginia. Freeh acknowledged that he learned for the first time that Hezbollah was active in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, while “Bandar agreed it was possible, but he doubted that was the case.”21 Following that meeting, the FBI worked with Prince Bandar in Washington, D.C. and the Mabahith, the Saudi secret police agency (comparable to the U.S. FBI), in Riyadh.

As the investigation moved forward, suspicions increasingly focused on Iran and its local adherents. The FBI learned from the Saudis that two months before the attack, they had arrested a Qatif native attempting to smuggle 38 kilograms of plastic explosives obtained in Lebanon.22 The Saudi authorities later arrested three others as well.23 They subsequently detained many Saudi Shi’as who were thought to be followers of Khat al-Imam and possible members of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz.

In the first chapter of his memoir, Freeh provided a detailed account of the attack, which included the role of each defendant. He did not mention his references, which suggests that the details were based on the investigation he headed from the U.S. side. Freeh’s narrative was no more than a summary of the formal charges against the group of 13 Saudi and one Lebanese Shi’a.24

Matthew Levitt also provides a more detailed account of the attack, especially the preparation and surveillance of Americans in Saudi Arabia.25 Unlike Freeh, Levitt was not personally involved in the case and his account draws on the details in the formal lawsuit against those mentioned above.

It is interesting that the narrative is exclusively from the U.S. side. There is no official account from the Saudi side. Nevertheless, Saudi media use a similar narrative, without any confirmation or denial from Saudi officials, although of course they would not spread a narrative rejected by the government.

The Saudi government has not shared its full formal account of what happened in the Khobar Towers bombing. The media have never mentioned the trials or the sentences. However, there are several Hezbollah Al-Hejaz charges against the defendants, including smuggling explosive materials and carrying out surveillance of Westerners (mainly Americans) in Saudi Arabia. This might be the result of a Saudi strategy to avoid being involved in any military retaliation by the U.S. against Iran. Or there may be other facts that the Saudis believe should not be shared for the best interest of the case itself.

There are also question marks around the American position as well, given the details presented by Freeh and in the lawsuit filed in June 2001. Hani al-Sayegh, one of the defendants, was transferred from Canada to the U.S. in 1997 and spent two years under arrest there before being transferred again to Saudi Arabia. It is unclear why the Clinton administration, of which Freeh was part at the time, handed al-Sayegh over, as they planned to file a lawsuit accusing him of participating in a “conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction against United States nationals.”26

While media outlets in both Saudi Arabia and the U.S. confirmed the accusations of Iranian involvement in the Khobar Towers bombing, some writers have argued that it was al-Qaeda, not a Shi’a group, that carried out the operation.

William J. Perry, the United States secretary of defense at the time of the bombing, said in an interview on the 11th anniversary of the attack that he “believe that the Khobar Tower bombing was probably masterminded by Osama bin Laden.” He continued, saying, “I can’t be sure of that, but in retrospect, that’s what I believe. At the time, he was not a suspect. At the time ... all of the evidence was pointing to Iran.”27

Gareth Porter, an American historian and investigative journalist, wrote an article entitled “Al Qaeda Excluded from the Suspects List,” shedding doubt on the outcome of the FBI investigation, which concluded by accusing Iran and some of its Saudi adherents of responsibility for the attack. According to Porter, “Freeh quickly made Iranian and Saudi Shi’a responsibility for the bombing the official premise of the investigation, excluding from the inquiry the hypothesis that Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda organization had carried out the Khobar Towers bombing.”28

Porter followed this article with another four pieces defending his alternative narrative of the bombing. Porter clearly has a negative perception of Freeh, seeing him as under Saudi influence. He wrote, “Freeh allowed Saudi Ambassador Prince Bandar bin Sultan to convince him that Iran was involved in the bombing, and that President Bill Clinton, for whom he had formed a visceral dislike, ‘had no interest in confronting the fact that Iran had blown up the towers,’ as Freeh wrote in his memoirs.”29 However, Porter did not comment on Freeh’s statement that “Bandar agreed it was possible [accusing Iran and Shi’a radicals, not Sunni radicals], but he doubted that was the case.”30 According to Freeh, the Saudi ambassador shared some information with the FBI director without expressing certainty about accusing Iran or a radical Shi’a group.

Porter based his argument on statements attributed to anonymous former “FBI officials involved in the investigation who refused to be identified.” Using an anonymous source to support a claim is one thing; however, it is hard to accept a narrative entirely built around one. That is to say, it is Freeh’s word against that of an anonymous individual.

Porter’s argument casts doubt on the credibility of the whole U.S. security system under both Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. But the question might be raised for Porter: Why would the U.S. respond in such a way? Moreover, the broader thrust of Porter’s work raises other questions as well, as it is clear he does not support strong ties between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, a point made in articles like “Time to End the Ruinous U.S. Alliance with Saudi Arabia.”31

Abdel Bari Atwan, the Palestinian former editor-in-chief of the London-based newspaper Al Quds Al Arabi who interviewed Osama bin Laden in 1996, insisted that the attack should be attributed to Bin Laden. He provided only very limited details to support the claim, saying, “The late Abu Laith al-Libi fought in Afghanistan and returned to Libya in 1994 in the hope of starting an Islamic revolution, subsequently fleeing to Saudi Arabia — where he was implicated in the Khobar Towers bombings — and then back to Afghanistan, where he has been one of the top commanders of AQAM battalions fighting with the Taliban.”32 His account includes no details about the role of Abu Laith al-Libi and the cell members that supposedly carried out this attack. It is worth noting that Bin Laden did not issue a statement claiming responsibility, as he typically did in most of the operations al-Qaeda carried out.

The absence of detailed narratives from either the Saudi and Iranian governments, or of any statement from al-Qaeda about the bombing, means that most accounts are based on the official U.S. version of what happened. Sensitive information or political considerations seem to be stopping the parties involved from sharing all of the details they have. Until that happens, observers will have to rely on the information available in the literature and media accounts.

Leading Names of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz

Most of the American references consider Abdelkarim Hussein Mohamed al-Nasser as “the alleged leader of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz.”33 The U.S. government offered a $5 million bounty for information leading to his arrest.34 However, there is not much information about him. He is not a well-known scholar or a preacher, nor is he a public figure in al-Ahsa, from which he hails. It is very interesting that the man who is supposed to be the chief of such an organization is so obscure and there is no description of his role within the group or any information or even rumors about what became of him. The leader of such an organization should have a clear role and sign his name to its pronouncements. Since he was recognized as the head of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz, he has never released any statement. However, since 1993, Hezbollah Al-Hejaz has issued very few statement concerning Saudi affairs.35

The most frequently cited name among the members of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz is Ahmed Ibrahim al-Mughassil, a.k.a. “Abu Omran” from Qatif. Since the early 1990s, all reports about the radical Saudi Shi’a group’s activities identify him as its military commander. He was traveling between Iran, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia, using fake passports and disguising his appearance. Based on details in the formal lawsuit, he was in charge of the Khobar Towers bombing and was responsible for planning the attack and training the members of the cell who carried it out. Just like for al-Nasser, the U.S. government offered a $5 million bounty for information leading to his arrest.36 In August 2015, he was apprehended in Beirut and transferred to Saudi Arabia.37

Another name frequently mentioned by the media is Hani al-Sayegh, who was the first person Freeh referenced in his book My FBI. Freeh even specified al-Sayegh’s alleged role in the bombing, suggesting he served as a driver of the scout vehicle and parked in the far corner of Building 131. Beside driving the scout vehicle, al-Sayegh, the lawsuit suggests, participated in various other aspects of the attack, including conducting surveillance reports in different parts of Saudi Arabia and helping to prepare the truck bomb at a farm in Qatif. Yet the idea that one person, let alone a small man suffering from asthma, could play this big of a role and carry out all of these tasks seems implausible. Al-Sayegh went to Canada in August 1996 and was arrested in March 1997 before being transferred to the United States that June. He agreed to assist U.S. officials investigating the bombing as part of a plea bargain. He later reneged on his agreement and requested asylum in the U.S.38 In October 1999, the Justice Department said that “the U.S. lacks sufficient evidence to charge Sayegh in an American court.”39 Thus, he was deported to Saudi Arabia, where he is currently imprisoned.

The rest of the names, either imprisoned in Saudi Arabia or with an unknown fate, are not as important as the three names mentioned. Their alleged contributions to the Khobar Towers bombing suggest they are “soldiers” rather than the leaders of the organization.40

The alleged non-Saudi actors who link Hezbollah Al-Hejaz to the IRGC or Lebanese Hezbollah are also quite unclear. There are some references, starting with an article written by Thomas L. Friedman in March 1997, in which he mentioned an “Iranian intelligence officer who goes by various code names, including ‘Sherifi’ and ‘Abu Jallal,’ acted as a liaison between Tehran and Saudi Shiites in Lebanon.”41 Also, in the lawsuit filed in June 2001 there is an unidentified Lebanese Hezbollah operative referred to in the indictment simply as John Doe. Those nicknames were likely given to the individuals by liaison officers charged with linking Hezbollah Al-Hejaz to Iranian agencies. However, it is not clear how U.S. security agencies like the FBI came up with these assumptions. For example, why is there only one Lebanese Hezbollah agent involved in the Khobar Towers bombing or one particular IRGC officer who deals with Hezbollah Al-Hejaz? And more importantly, these assumptions need to be unpacked and more detail provided explaining the premises that led to these conclusions.

The 2011 Uprisings

Following the Khobar Towers bombing, Iran’s adherents, including Hezbollah Al-Hejaz, were absent from the scene. Until the Arab Spring uprisings occurred in different parts of Arab world, Iranian agents were not a serious threat to the governments of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Starting in 2011, however, some GCC governments once again began clearly accusing Iran and its local agents of carrying out acts of sabotage.

In February 2011, uprisings began in Qatif, one of the kingdom’s major Shi’a cities, at a time when similar events were taking place across the region, including in neighboring Shi’a-majority Bahrain, as part of the Arab Spring. While the details are beyond the scope of this article, it is worth briefly exploring the role of Iran’s adherents during the uprising (2011-17).

The slogans used by protesters were very general, calling for freedom, Shi’a rights, dignity, and anti-discrimination. However, on March 9-10, 2011, the protesters started carrying the pictures of al-sujana’ al-mansiyun (the forgotten prisoners), referring to the nine prisoners of the Khobar Towers bombing. At that time, the Saudi authorities issued several statements accusing Iran of involvement in Saudi affairs, just like the Bahraini government. At the same time, official Iranian statements supported the protests in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain and blamed the two royal governments for the tensions among their citizens.

There is no detailed narrative of Iranian involvement in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province between 2011 and 2017, but it is hard to imagine that the Iranians were merely observing the scene. Based on local references, some Saudi Shi’a individuals acknowledged receiving training in Iran or Iraq. Some of them were convinced to visit Iran or Iraq to perform religious pilgrimages or for other similar reasons and found themselves in training facilities. According to these accounts, there was no instruction to carry out attacks, nor were weapons supplied; they were merely given basic training. The Saudi government has not released any details regarding Iran’s involvement in the region at that time — perhaps for security or political reasons.

On March 19, 2013, the Saudi authorities announced that they “had arrested an 18-member spy ring, including an Iranian, a Lebanese, and 16 Saudis.”42 The number of detainees subsequently increased. Saudi courts later sentenced 15 Saudis to death for spying for Iran and 15 others to prison terms ranging from six months to 25 years.43 On April 23, 2019, 11 members of this group were executed.44 While the Iranian authorities denied recruiting spies in Saudi Arabia, Riyadh accused Tehran of deep involvement in its internal affairs.

Nevertheless, during this period, Hezbollah Al-Hejaz has not been officially held responsible for any of these illegal activities. However, the Saudi authorities did include it in their list of terrorist groups in March 2014.45 The UAE followed suit and included Hezbollah Al-Hejaz in its list of terrorist groups in November of the same year.46

Conclusion

Longstanding tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia remain a major issue as the two countries have their own, very different perspectives on the future of the Middle East. Saudi Arabia accuses Iran of meddling in its domestic affairs, while Iran denies such claims. Part of this tension is due to the Saudi Shi’a community, as Riyadh accuses Tehran of recruiting individuals to serve its interests through groups like Hezbollah Al-Hejaz, the secret organization allegedly linked to the IRGC.

Khat al-Imam, the followers of Khamenei’s marj’aiyyah, have been suspected of being members of Hezbollah Al-Hejaz. As this paper explains, there is a limited connection between Khat al-Imam and Hezbollah Al-Hejaz: Many of the followers of Khat al-Imam consider Khamenei as a marj’a and are inspired by Khomeini’s Irfan, which leads them to admire some apolitical Iranian clergy such as Bahjat Foumani and Javadi-Amoli.

Yet the Iranian influence upon some members of the Saudi Shi’a community is undeniable. It is difficult to determine how extensive it is, however, given the limited availability of information about the attacks that occurred in 1990s, especially the Khobar Towers bombing.

Recently, the Saudi government has carried out some reforms to its deradicalization efforts, in part with an eye to countering the sectarian discourse in the national media. In the last four years, Saudi media outlets have begun to differentiate Iran’s ambitions as a regional power from Shiism as an Islamic sect. This change in attitude by Saudi media outlets has been well received by the Saudi Shi’a community, as they do not want to be targeted by their fellow citizens and accused of being a fifth column for a foreign country.

While many Saudi Shi’a were inspired by Khomeini’s charisma in the 1980s, they did not consider him the grand marj’a and his marj’aiyyah was not widely popular in Saudi Arabia. This changed with the youth generation of the 1990s — those who were born a few years before the Iranian revolution — who started to emulate Khamenei as their grand marj’a. Yet the majority of those who did so claimed their relationship with him was an ordinary religious one, just like the followers of Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Sistani or other marj’as. The question that should be asked here is: What happens after Khamenei? Would they follow the next supreme leader of Iran? If the answer is yes, this suggests that for Khat al-Imam the marj’aiyyah has gone beyond just a religious position to become a political one as well. This scenario will become clear if the majority of Khat al-Imam adopts the marj’aiyyah of the next supreme leader. Many people expect Sayyid Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s current president, to step into that role and we should wait to see if he — or whoever else takes on the position — will gain a sizeable following for Tehran’s marj’aiyyah.

While plenty of questions remain about Hezbollah Al-Hejaz, this paper reveals the background and limitations of the major references on the topic and provides a solid narrative based on the available information, without following the propaganda that serves the agenda of various parties.

About the Author

Dr. Abdullah F. Alrebh is Associate Professor in Sociology of Religion and Sociological Theory at Grand Valley State University and a Non-resident Scholar at MEI. His research focuses on politics, culture, religion, and authority of Saudi Arabia, Persian Gulf, and Islam. He has published a number of articles (peer-reviewed and think tank) spanning several issues pertaining to religious, authority, and education with a primary focusing on Middle Eastern countries in general, and Saudi Arabia in particular. His upcoming book is titled, Covering the Kingdom: Saudi Arabia in Western Press during the 20th Century. He is the Editor of the Michigan Sociological Review.

Top image by Aritra Deb, Shutterstock.

MEI is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.

Endnotes

- Khalaji, Mahdi (2006). The Last Marja: Sistani and the End of Traditional Religious Authority in Shiism. Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Pp. V. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/media/3502?disposition=inline

- Matthiesen, Toby (2010). "Hizbullah al-Hijaz: A History of The Most Radical Saudi Shi'a Opposition Group." The Middle East Journal 64, no. 2 https://muse.jhu.edu/article/380306

- Sahimi, Muhammad (January 3, 2016). Who Will Succeed Ayatollah Khamenei? HuffPost News. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ayatollah-khamenei-successor-_b_8908618

- The Shirazis’ activities in Saudi Arabia were limited to media propaganda; however, they were active in Bahrain and some Saudi members participated in the 1981 Bahraini coup attempt.

- Matthiesen, T. (2014). The other Saudis: Shiism, dissent and sectarianism (Vol. 46). Cambridge University Press. P. 133.

- Bowden, Mark (May 2006). The Desert One Debacle. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/05/the-desert-one-debacle/304803/

- Alrebh, Abdullah (March 2021). Radical shiism and Iranian influence in Saudi Arabia. Interview with European Eye on Radicalization. https://eeradicalization.com/radical-shiism-and-iranian-influence-in-saudi-arabia/

- Matthiesen (2014) pp. 133-134, see also Matthiesen (2010) p. 184.

- The incident took a place in Mecca, the street battles beside the Grand Mosque. The clashes began when some Iranian pilgrims massed after Friday's prayers for a political demonstration, which is banned by the Saudi authorities. The pilgrims, who were brandishing pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini, chanted, ''Death to America! Death to the Soviet Union! Death to Israel!'' The incident caused the death of 400 pilgrims. Source: The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/02/world/400-die-iranian-marchers-battle-saudi-police-mecca-embassies-smashed-teheran.html

- Matthiesen (2010), pp. 183-184.

- An interview with a former member of the IRO who was very close to al-Mughasal for few years. The identity of this member is remained anonymous based on his requests.

- Fawzy, Muhammad (January-March 2015). "Iran and Hizbullah: A Very Special Relationship." Annals of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University, (43) 453-506.

- Ibrahim, Fouad N. (2006). The Shiʻis of Saudi Arabia. London: Al Saqi. P. 142.

- The archive of Addiyar (Lebanese newspaper).

October 27, 1988: https://addiyar.com/article/607793-الصفحة-11-27101988

January 10, 1989: https://addiyar.com/article/643221-الصفحة-10-1011989 - Teitelbaum, Joshua (Nov 14, 1996). Saudi Arabia's Shi`i Opposition: Background and Analysis. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/saudi-arabias-shii-opposition-background-and-analysis

- Matthiesen (2014) p. 137.

- All those three are currently under detention and trial by the Saudi authorities.

- Jamieson, Perry. D. (2008). Khobar Towers: Tragedy and Response. Government Printing Office. Pp. 9-13.

- Riedel, Bruce (June 21, 2021). Remembering the Khobar Towers bombing. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/06/21/remembering-the-khobar-towers-bombing/

- Cordesman, Anthony H. and Nawaf Obaid (January 26, 2005). Al-Qaeda in Saudi Arabia: Asymmetric Threats and Islamist Extremists. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Washington, DC https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/050106_al-qaedainsaudi.pdf

- Freeh, L. J., & Means, H. B. (2006). My FBI: Bringing down the Mafia, investigating Bill Clinton, and fighting the War on Terror. MacMillan. P. 9.

- Freeh & Means (2006), p. 10.

- Kirkpatrick, David D. (August 26, 2015). Saudi Arabia Said to Arrest Suspect in 1996 Khobar Towers Bombing. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/27/world/middleeast/saudia-arabia-arrests-suspect-khobar-towers-bombing.html

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA- ALEXANDRIA DIVISION (June 2001 TERM). Conspiracy to Kill United States Nationals. CRIMINAL NO: 01-228-A. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB318/doc05.pdf

- Levitt, Matthew (2015). Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon's Party of God. Georgetown University Press. Pp. 181-208.

The same story was repeated by Levitt in his article titled “Anatomy of a Bombing: How Ahmed al-Mughassil Bombed Khobar Tower and Walked Free—Until Now” which was publish by Foreign Affairs in September 1, 2015. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/lebanon/2015-09-01/anatomy-bombing - UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, p. 1

- United Press International, Inc. (June 6, 2007). Perry: U.S. eyed Iran attack after bombing. https://www.upi.com/Defense-News/2007/06/06/Perry-US-eyed-Iran-attack-after-bombing/70451181161509/?u3L=1

- Porter, Gareth (June 22 2009). EXCLUSIVE-PART1: Al Qaeda Excluded from the Suspects List. Inter Press Service. https://www.ipsnews.net/2009/06/exclusive-part1-al-qaeda-excluded-from-the-suspects-list/

- Ibid.

- Freeh & Means, P. 9.

- Porter, Gareth (October 26, 2018). Time to End the Ruinous U.S. Alliance with Saudi Arabia. Common Dreams (originally published with Middle East Eye). https://www.commondreams.org/views/2018/10/26/time-end-ruinous-us-alliance-saudi-arabia

- Atwan, A. B. (2013). After bin Laden: Al Qaeda, the next generation. The New Press. P. 202.

- FBI Most Wanted List. https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/wanted_terrorists/abdelkarim-hussein-mohamed-al-nasser

- The announcement is available on the Department of Justice website: https://rewardsforjustice.net/rewards/abdelkarim-hussein-mohamed-al-nasser/

- For example, the following statement concerns the executions carried in March 2022, the statement was published in a Bahraini dissenting website: https://www.al-abdal.net/32273/حزب-الله-الحجاز-مجزرة-شعبان-الكبرى/

- FBI Most Wanted List. https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/wanted_terrorists/ahmad-ibrahim-al-mughassil

- Riedel, Bruce (August 26, 2015). Captured: Mastermind behind the 1996 Khobar Towers attack. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2015/08/26/captured-mastermind-behind-the-1996-khobar-towers-attack/

- Levitt, p. 200.

- Karon, Tony (October 5, 1999). The Curious Case of Hani al-Sayegh. TIME. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,31972,00.html

- All the names are available in the formal in UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, p. 1

- https://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/25/opinion/stay-tuned.html

- USA Today. (March 26, 2013). Saudi Arabia says spy ring worked for Iran. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2013/03/26/saudi-arabia-spy-iran/2020799/

- BBC. (December 6, 2016). Fifteen Saudi Shia sentenced to death for 'spying for Iran'.

- Hubbard, Ben. (April 23, 2019). Saudi Arabia Executes 37 in One Day for Terrorism. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-executions.html

- Youssef, B. A. & Adam Baron (March 7, 2014). Saudi Arabia declares Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group. Kansascity. https://www.kansascity.com/2014/03/07/4873900/saudi-arabia-declares-muslim-brotherhood.html#storylink=cpy

- Emirates News Agency. (November 15, 2014). The Council of Ministers approves the list of terrorist organizations. https://web.archive.org/web/20141117230142/http://www.wam.ae/ar/news/emirates-arab-international/1395272465559.html