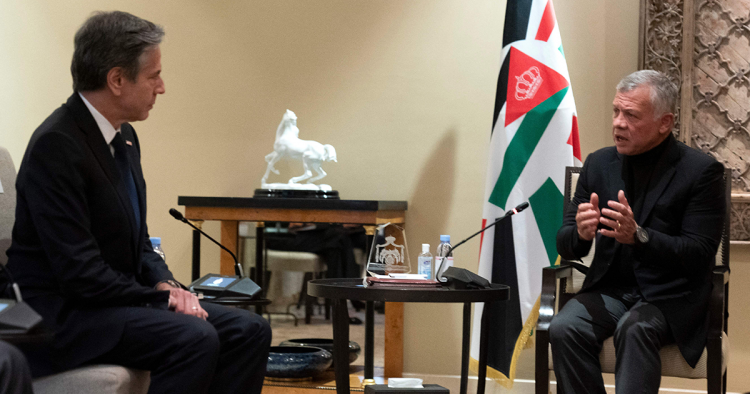

In the final leg of his recent Middle Eastern tour, which included visits to Jerusalem, Ramallah, and Cairo, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken stopped in Amman for half a day to meet King Abdullah. Blinken’s main objective was to support the shaky cease-fire reached between Palestinian factions in Gaza and Israel after an 11-day military showdown. In a press conference he held later in the Jordanian capital on May 26, Blinken said that “the leadership of His Majesty King Abdullah was crucial, as it always has been in different issues, his role was essential in reaching a cease-fire in Gaza.”

But while President Joe Biden called Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi a couple of times during the crisis, it was Vice President Kamala Harris who phoned the king to discuss the ongoing fighting.

Jordanians were less confident of their government’s role in ending what most saw as “Israeli aggression against Gaza.” Even before the recent military clash Jordanian pundits, some known for their close ties to the government, were critical of the lukewarm official response to the Israeli provocations of Palestinians at Al-Aqsa Mosque and in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in East Jerusalem, which began in the early days of Ramadan. Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi took more than two weeks before commenting on the Israeli escalations in a tweet. But on May 10 he was the first Arab foreign minister to meet with Blinken in Washington. Safadi once again repeated his warnings that “Jerusalem was a red line” and that “Israel was playing with fire.”

But aside from these clichés, which included Jordan’s reiteration that the two-state solution was the only path to a just settlement, there was little action. The king called Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and later sent Safadi to meet him. King Abdullah also communicated with Egyptian President el-Sisi when war broke out between Gaza and Israel, urging an immediate cease-fire.

Amman’s limited leverage

As Israel defied Jordanian warnings and resumed its incursions into Al-Aqsa while tightening its siege of nearby Sheikh Jarrah, whose residents were threatened with evictions, Jordan could do little more than issue statements denouncing the moves. Meanwhile, the public response to the onslaught on Gaza was unprecedented. For the duration of the Israeli attacks, thousands of Jordanians held daily protests near the heavily guarded Israeli embassy in West Amman. Jordanian lawmakers sent a memorandum calling on the government to expel the Israeli ambassador and recall Jordan’s envoy in Tel Aviv. The government promised to “study” the memo but nothing happened.

The attacks on Al-Aqsa were seen as direct challenge to King Abdullah, who is the custodian of Muslim and Christian holy places in East Jerusalem. But ties between the king and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu soured many years ago, particularly over continued incursions by Jewish extremists. The king has not spoken to or met with Netanyahu for years.

By the same token, Jordan has had no sway over Hamas, the de facto ruler of Gaza, since it expelled its leaders from Jordan back in 1999 in a bid to limit the influence of the country’s Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas’s leaders were subsequently welcomed by Qatar. Ironically, the Sisi regime, which had demonized Hamas for its close ties with former Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi, maintained contacts with the group and employed its ties to mediate between Israel and the Palestinian factions in Gaza.

Jordan had one main Palestinian ally: Abbas, who also could do nothing to stop the war or prevent his people from holding nation-wide demonstrations against occupation and the Israeli attacks on Gaza and Al-Aqsa. It is difficult to understand what role Jordan could have played in the latest faceoff. But in a press conference Safadi held with his Egyptian counterpart Sameh Shoukry in Amman on May 24, the Jordanian foreign minister said that contacts had been made with Hamas during the past weeks, without elaborating further.

A changing regional environment

Jordanian commentators warn that Amman is losing its historical role as a main interlocutor in relation to the Palestine Question. They say that while Egypt considers Gaza as part of its national security, Jordan should underline that the future of the West Bank is integral to its own national security. They point to an existential threat in the form of Israeli ethnic cleansing of Palestinians through displacement and evictions that could lead to transfer, pushing Palestinians to the East Bank. The king has warned that Jordan will never be an alternative homeland for the Palestinians.

One former minister and political analyst, Muhammad Abu Rumman, in an article published in the Qatari-based New Arab news site on May 23, pointed out that there was a new regional geopolitical reality that necessitates that Jordan review its ties with Turkey, Iran, Syria, and Iraq to preserve its national interests. That reality began to form with former U.S. President Donald Trump’s so-called “deal of the century,” which Jordan rejected at the risk of damaging its special ties with Washington. But even as the deal fell through, Trump was able to sponsor normalization agreements between Israel and two Gulf states, thus diminishing Jordan’s role as a historical buffer between Israel and the Gulf.

The erosion of the Jordanian role comes at a difficult time for the kingdom, which is battling a stalled economy, a rise in unemployment and poverty figures, a spike in foreign debt, and the effects of the coronavirus pandemic. Jordanians are also wary of reports that some of the country’s closest allies were allegedly involved in what became known as the “seditious plot” in March involving former Crown Prince Hamzah and two Jordanians with close ties to Saudi Arabia.

For Jordanian observers it was Cairo and Doha that emerged as the key brokers of the cease-fire between Israel and its Gaza foes. Jordan continues to be increasingly dependent on U.S. military and economic support and last March it revealed that it had signed a controversial defense agreement with Washington without passing it through parliament. With Gulf financial support almost gone, Jordan is trying to build a trilateral economic and political alliance with Iraq and Egypt, two countries with their own internal challenges.

Meanwhile, the belief here is that the Biden administration will seek to manage the Israel-Palestine conflict rather than launch a new peace process while rehabilitating the unpopular Palestinian Authority and its ailing president.

In the view of one critic Jordan found itself stuck in a political no man’s land during the latest crisis and as a result it must rebuild its regional alliances to boost its geopolitical value. At a time when old foes are beginning to reconcile — Egypt and Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran, Egypt and Qatar and Turkey and Saudi Arabia — it is imperative that Jordan realizes that the region is changing and that Amman must adopt a new approach by talking to parties like Turkey and Iran to preserve its national security, especially when it comes to maintaining its role in East Jerusalem.

And with Hamas emerging as a key player in the divisive Palestinian politics, Amman must not be shy of reinstating official contacts with the group at a time when even some European countries have hinted that they could initiate indirect dialogue as well. This view is becoming more relevant as observers believe the recent lull in fighting will not last and that a new round of violence is certain to occur in the near future.

Osama Al Sharif is a journalist and political commentator based in Amman. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by ALEX BRANDON/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.