“The story of the fall in Kurdish carpets is a sad one but nothing new,” said Lolan Sipan, the director of the Textile Museum in Erbil, the capital of Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdistan region. The decline in textile production is uniquely tied to Kurdish history and conflict. It also highlights the irony that while the Iraqi Kurds have greater sovereignty now than ever before in modern history, they are also simultaneously experiencing cultural decline. Today, only a few weavers remain and there is a risk that their knowledge will not be passed on to the next generation.

The “rug belt,” which skirts across the Islamic world, is famed for carpets. Turkish rugs have gained worldwide recognition for their characteristic symmetrical knots, known as “ghiordes.” Carpet weaving in Iran is intrinsically linked to Persian culture, and its intricate designs have been fawned over in Europe for centuries. In the remote and mountainous highlands of Iraq, bound by the Turkish and Iranian frontiers, lies the Kurdish heartland, where the majority of Iraq’s textiles have historically been produced. The lesser-known Kurdish rug stands tall within the crowded textile arena with its riotous mélange of brash colors and pagan symbolism, as well as its everyday uses.

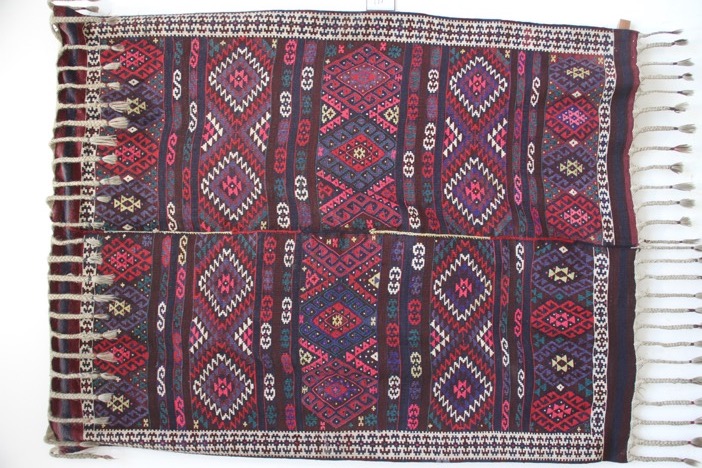

Kurdish carpets, kilims, and labads display motifs that include Zoroastrian symbols as well as images of animals and humans, a practice frowned upon in Islam. According to William Eagleton’s seminal work, An Introduction to Kurdish Rugs and Other Weavings, the mostly female weavers abhorred empty space within their compositions. As such, rugs tended to be cluttered with motifs. These textiles are notable for their bold and rustic compositions, characterized by the use of shades of orange and pink. The weavers preferred to create textiles with strong colors found in nature, and made use of the wool of the fat-tailed sheep, which is ideal for absorbing natural, plant-based dyes. Lastly, while most other weaving traditions in the “rug belt” produced predominantly merchandise, Kurdish textiles were woven primarily for everyday use.

Furthermore, differences also exist in the style and purpose of textiles produced by nomadic versus pastoral Kurdish tribes. Nomads wove portable, light screens to cover the walls of their tents along with saddlebags to store everyday essentials. Some even wove animal trappings for hunting. The Herki, the largest nomadic tribe within Kurdistan, generated some of Iraq’s most prolific weavers. Pastoral tribes, by contrast, could afford to produce heavier textiles since they were settled in villages. Those living in the plains were further from the flora of the area and thus had less access to colors and fewer to choose from. As a result their carpets tended to be simpler in design. While the textiles of other weaving cultures were influenced by European and American preferences for smaller carpets, this was less the case among the settled and relatively isolated Kurds. They continued to weave long runners that were placed along the walls of their reception areas as cushions.

Conflict and displacement

Kurdish culture, however, has been disrupted throughout modern history, rife with globalization and conflict. The praxis began to change as tribes interacted with the outside world. Synthetic dyes, which originated in England at the turn of the twentieth century, became widespread due to their affordability and ease of use. Although the Kurds were the last of the “rug belt” weaving traditions to succumb to synthetic dyes due to their relative isolation, such dyes eventually found their way into Kurdish textiles as well, and their use became widespread by the late 1950s.

The decline of Kurdish weaving traditions can be traced to the heavy fighting between Kurds and successive Iraqi regimes beginning in 1960. Under the Ba’athists in Iraq, Kurdish tribal culture was uprooted, making conflict a fact of life. From 1975 onward, Saddam Hussein’s regime conducted a series of “Arabization” campaigns to deport, depopulate, and destroy non-conforming communities. Nomadic Kurds, included in this category, were forced to abandon traditions like carpet weaving following their displacement.

Later, in 1980, Iraq’s invasion of the Arab-majority Khuzestan Province in Iran led to a costly eight-year war. Fighting was concentrated along the Iran-Iraq border, an area where many nomadic Kurds raised animals and produced textiles. Both Iran and Iraq littered the mountainous region with millions of mines, while security zones along the border interfered with nomadic movements and flocks of sheep and goats were largely decimated. In the latter half of the war, Ali Hassan al-Majid, a cousin of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, launched the Anfal campaign against the Kurds. This led to the destruction of over 4,000 Kurdish villages along with their vegetation, livestock, and water sources.

In 1991, the UN Security Council imposed crippling sanctions on Iraq in response to its military invasion of Kuwait. The sanctions persisted after the end of the Gulf War in 1991. Saddam Hussein implemented a simultaneous economic blockade of Kurdistan due to persistent fighting between Kurdish and Iraqi forces. As the Kurds suffered under double sanctions, exploitative merchants bought tens of thousands of rugs from desperate and starving villagers in need of money, shipping them out of the country in bundles to Turkish dealers. This fire sale resulted in the permanent removal of some of the most impressive pieces of Kurdish heritage from Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) became the ruling body of the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region in 1992. Despite this new autonomy, Sipan fears that the knowledge of Kurdish textile heritage and their important role in Kurdish life may be lost forever. In an attempt to save this heritage, Sipan secured funding for six of the remaining Kurdish weavers to teach 40 women in 2008. Similarly, he aims to conserve and display this heritage through his collection of over 2000 textiles at the Textile Museum in Erbil. Despite these efforts, there are only a handful of weavers left. A recent livelihoods project, managed by the International Organization for Migration, had to shift its scope from Kurdish weaving to the imported practice of needlepoint after the program could not find a weaver to lead the workshop. Furthermore, no courses on the study of textiles exist at any university in Iraqi Kurdistan. Sipan has been lobbying, to no avail, for the Iraqi Kurdistan Ministry of Culture to support projects that produce traditional textiles.

Globalization and collective memory

Sipan isn’t hopeful, seeing the current generation’s interest in this dying tradition eclipsed by globalization. “The area is modernizing very quickly and Kurds here are experiencing an identity crisis, giving little attention to our past,” he said. Strangely, as Kurds have gained greater autonomy, they seem to be losing their culture. The lack of a long-term strategic plan by the KRG to conserve traditional Kurdish crafts through subsidies and other protective measures may stem from the Iraqi Kurds’ historic need to prioritize everyday survival. This lack of planning may also be due in part to the belief among many Kurds that their autonomy is beholden to Western countries and that any deviation in looking toward their past, particularly in celebrating tribal activities, may affect the perception of their synergy with the West. It remains unclear how the loss of weaving and the textile tradition will affect Kurdish identity.

Maurice Halbwachs, a famous French philosopher and sociologist, developed the concept of collective memory to indicate a type of memory shared by an entire society. Older generations celebrate the textile custom as a uniquely Kurdish craft. Sipan elaborated that as a boy, he went with his father and grandfather to the Zagros mountains to see this centuries-old process of weaving firsthand. “The younger generation will never have such a memory to shape their interest,” he lamented. Instead, Kurdish youth are fixated by American and European culture and have little interest in such “outdated” crafts. Tribal weavings are an important marker of Kurdish identity that cannot be produced once the necessary skills have been lost. However, if the practice is sustained, it can act as a form of transgenerational communication of Kurdish culture and tradition.

Karani Jamil, a renown Kurdish painter, has a slightly more optimistic outlook, predicting that the influence of textiles will live on. “The rich motifs, colors, and symbols in our carpets have been a major influence on my art.” While studying at the College of Fine Arts in Baghdad in the 1970s, Jamil remembers his instructor who taught him and his peers about the themes and symbols in Kurdish textiles. “Their designs have been woven into many of my paintings,” Jamil added. He argues that art institutes should include standard lessons on textile design and production to stoke appreciation for them among the new generation of artists.

This is not the first time we have heard that the end of a weaving tradition is near. While the risk is real, both Kurds and their traditions are tenacious and resilient. The pendulum of local and global tastes may well swing back, reigniting interest and spurring production. For example, some restaurants across Iraqi Kurdistan have begun to use Kurdish textiles for decoration, and young brides and grooms can be seen taking their wedding pictures at the textile-adorned café inside the Kurdish Textile Museum.

However, what is certain is that with the end of wide-scale nomadism, the need for a range of everyday woven products has come to an end. Kurdish textiles will have to transform from their former role of utility to one of beauty and cultural significance, similar to that of many other weaving cultures today. The change from the practical to the decorative may be the only way of preserving this distinctly Kurdish tradition.

Photos courtesy of the Kurdish Textile Museum

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.