The essays in this series deal with transregional linkages between the Middle East and Asia. As a whole, the series explores the "vectors" of religious transmission and the consequences of or implications of such interactions. More ...

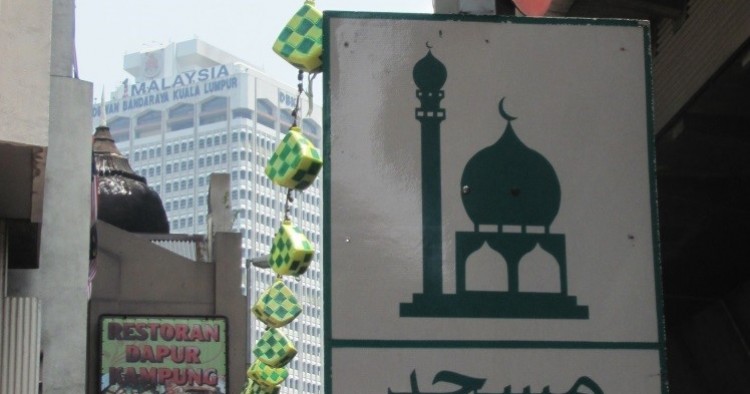

In the corporate high-rises of Kuala Lumpur, a new kind of Muslim corporate elite has emerged, the inheritor of decades of Malay-Muslim-focused economic development and Islamic intensification.[1] Like any modern capitalist elite anywhere, its business leaders invest in assets, enter into global and local deals and contracts, manage costs, seek increased profits, expand enterprises, and pay taxes. Their companies, whether large or small, follow the structural and hierarchical form of modern corporations everywhere. As managers, members of this elite supervise, set policy for, train, and evaluate the performance of personnel in the middle and lower ranks of their organizations. But, as pious believers, they also increasingly seek to demonstrate in their businesses total compliance with core sharia values.

This brief ethnographic essay explores developments in Malaysia’s Islamic economy, not by focusing on the technical, sharia-based structuring of investment products, but on the corporate culture that has emerged alongside it. Like the elite I study, I define an “Islamic economy” in a way that includes both sharia-compliant banking and finance — an area in which Malaysia has emerged as a global leader[2] — and the ethical and moral template for economic life and the human engagements that sharia is claimed to generate. As anthropologists increasingly recognize that corporations “pervade the social and material fabric of everyday life ... shape[s] human experience ... the physical and natural world; and the subjects who labor within them, consume their products, and live downstream of them,”[3] the Muslim-run corporations I study in Malaysia have become key sites for understanding the conjuncture of Islamic economics, sharia, and modern global capitalism. As such, “corporate Islam,” the emplacement of Islamic piety and practice in Malay-Muslim corporate life, addresses the ways in which the spread of global capitalism has transformed the lives of some Muslims in Malaysia and is transformed by them, but also how capitalism in this setting has empowered the movement of sharia into the corporate workday, the long stretch of hours between waking and sleeping in which many of them labor.

The corporate Malay-Muslim business men I spoke to—and, indeed, at the highest levels of corporate life I found mostly men (a point I return to below) — are sophisticated, globally mobile, and cosmopolitan capitalists. But to use a term I heard frequently among them in Kuala Lumpur, they describe themselves as “men of the mosque and the market.” As “men of the market,” the contemporary Malay-Muslim corporate executives did not disdain capitalist wealth; they eagerly sought it. But, as “men of the mosque,” they insisted they did so in compliance with sharia, practicing and managing a business in ways that the Prophet Muhammad had approved. Within their enterprises and guiding their business knowledge, Islam had become part of everyday corporate conversation. Its practices and pieties had become part of daily experience. They read the Quran, the sunnah, and hadith, for moral instruction in business — in effect, as management texts. They studied Islam in consultation with corporate-minded sharia scholars and advisors, themselves often globally recognized consultants with offices not only in Kuala Lumpur but in places like Dubai and London. From these experts, they sought business knowledge, ethical direction — as well as advice on sharia-compliant financing and investments, often conversing with them daily on all matter of business.

Even the most globally successful of the “men of the market” I interviewed preferred to think of themselves as mere “business men” or “simple traders” — in that sense, like Muhammad, who was a trader before he became the Prophet. They wished, they said, to seek nothing grander than to earn the ethically legitimized and socially balanced commercial success the Prophet himself had achieved in his early profession and later as the “best manager” of the citizens in ancient Medina. But, as they thought about the contemporary Arab world, the corporate leaders I interviewed were disdainful of today’s Arabs, Wahhabis and Salafists, who often, they believed, set out a vision of Islam that would return Muslims to the “dark ages.” Referring to themselves as mujahideen and their businesses as jihad, they assured me that Malaysia’s Islamic message to the post-9/11 world was “Islamic banks, not bombs!” The implication was that through their actions, Islam could remake the world, corporate-style, spreading Islam via ethical economic development in a way that no Muslim nation had yet done. Corporate Islam, successful modern capitalism based on sharia principles, in their view, would then place Malay Muslims like them at the very center of the modern Muslim world as “Islam’s economic ambassadors.” In so doing, they could also rectify what Patricia Martinez called Southeast Asian Muslims’ “core-periphery” problem,[4] which had long cast them as too distant from the Arab core to claim equality with it. Now, modern men of the mosque and the market, they were, they envisioned, potentially superior to it as makers of a new and economically vibrant Islam, and, because of its ethical concerns, superior to the Western capitalist world as well.

The Western economic system was collapsing, ready for, as one banker put it, “a friendly take-over” by Islamic economics. Evidence was everywhere — all the major U.S., London, and Hong Kong banks were setting up Islamic banking divisions in Malaysia. The banker also pointed to how powerful the allure of Islamic economics was to non-Muslim Malaysians, describing how local Chinese capitalists frequently turn to Islamic banks seeking more favorable and transparent lending policies and Chinese customers now represent an increasing number of account-holders in pursuit of fixed lending rates. Soon, many corporate leaders hoped, the entire Malaysian economy might be sharia compliant, and they believed that Malaysian Chinese capitalists whose economic hegemony Malays had been contesting for over a generation[5] could eventually be subsumed within Malaysia’s Islamic economy. Later, they said, sharia-ization could be extended to all aspects of modern Malaysian life; corporate Islam, in effect, would give way to political Islam.

But beyond imagining Islam’s financial future in Malaysia and beyond it, what were sharia’s specific business practices that guided the Muslim business elite? At the most basic level, muamalat — one of the four areas of sharia — means conducting commercial and financial exchanges according to sharia’s prescriptions. Ample references in the Qur’an and the hadith reflect good business practices such as keeping true to one’s word, maintaining justice in economic transactions, avoiding riba (interest, or more accurately, usury) paying workers fairly and on time, and so on. Corporate executives and owners I met worked with sharia scholars and advisers to “detoxify” their balance sheets, convert riba-based loans to sharia-compliant ones, shift investments from conventional banks to Islamic ones, and follow new rules for paying what is called “corporate zakat” in Malaysia.[6] But little in business life, corporate leaders said, was as clear-cut as merely choosing between a haram or halal practice. Constant input from business-minded sharia scholars for a fatwa or legal opinion was acutely necessary as they engaged in the operation of everyday Islamic business. The sharia advisory elite in Malaysia claims to have greater professionalism and expertise than in Arab countries, and as consultants to both financial institutions and corporate leaders, uses ijtihad, multiple schools of Islamic jurisprudence, and updated principles to balance sharia with the complex realities and necessities of seizing maximally advantageous opportunities for growth.

There are difficult questions to be answered in the profitable operation of corporate business in contemporary Malaysia, a country which Transparency International ranks high on the global corruption index.[7] Practices like bribery and “pay-offs” and alliances between politicians and business men are very much present in the Malaysian economy. Did that mean one must never do business with politically affiliated companies? To avoid these opportunities would limit owners of some of the firms I studied—such as those that provided services to other businesses—to a very small range of potential clients and customers. Yet the business men I interviewed claimed to follow the sharia ethics and “transparency” required by muamalat but still found ways to engage with corrupt others.

One business owner described how his company had been offered a very significant project from a contractor who, he learned, had gotten the job by paying a large bribe to a politician. Calling upon a sharia scholar for a fatwa, he learned that it was “perfectly ethical” to do his “piece of the project” for a business that, unlike his, was not ethical. That left him in the clear to do business with people whose practices he disdained, as long as his own practices remained sharia compliant and officialized by a sharia scholar. Other business men I knew said that while they had been forced to pay a bribe to get a large piece of business from the ruling political party, they “balanced” it out by making a comparable payment to the Islamic opposition party. Ultimately strategies of this kind meant they could maintain close and profitable business relationships with the very corporate men — allied with politicians — from whom they ethically distinguished themselves. They also actively did business with such people in hopes that they could convince other Muslims to change their ways and to think more about the wealth accumulated in good deeds or blessings, barakah, than about worldly returns. Barakah was ultimately what mattered in the next life, in what one sharia scholar told me is the “bank of the hereafter.”

Indeed, even the best-situated often insisted that money mattered little to them; their goal was not to hoard wealth but circulate it and earn more barakah. This, corporate leaders told me, was the very “point” of the Islamic economy. Wealth, they believed, is a “test” from God, who sees when you hold it selfishly, or, conversely, spend it for fisabil’Allah — that is, for Allah’s sake. But if barakah in the bank of the hereafter — which cannot be seen in this world though it will be revealed in the next — was what the corporate sharia elite I met claimed to seek, what then explained the company car and driver, the executive compensation, and, finally, the elite managerial position that clearly differentiated them from the ordinary personnel who worked in their corporations?

Sharia establishes via the hadith that compensation should reflect levels of skill and responsibility; corporate executives and owners were well compensated, sharia had taught them, because they were the most skilled and responsible people in the business. They described to me the difference between equity — that is, fairness and justice — and equality, which presumes sameness. In Islam, one corporate owner told me, “It is stated that all men are equal, but some have greater knowledge than others.” Salaries, an economic measure of value, were, therefore, equitable in their corporations because they measured different abilities and responsibilities. Corporate elites told me that God requires the knowledgeable members of society to rise up as leaders — it is an obligation to use one’s gifts and skills to serve God and others (and to be compensated for those skills accordingly). They used the Arabic term khalifah, meaning a “steward” or “vicegerent” of Islam. The term originally referred to the khalifah rasul Allah or caliph of the messenger of God; today in corporate Islam, it is a powerful managerial term: it refers to the men at the top of the organization who have control over those who work beneath them. But as khalifah, the corporate elite I met increasingly sought to control not only their employees’ work lives, but also their religious conformity. As Islamic orthodoxy — and the policing of everyday Muslim lives[8] — becomes more the norm in Malaysia, workplace behavior and comportment have fallen under the sharp eye of increasingly pious managers. While expansive and flexible muamalat often regulates how the corporate sharia elite engages with money, economic opportunity, and the political and social relationships that money generates, I found that the sharia that structures human-resource practices by contrast reflects a more conservative and uniform application of sharia.

Corporate Islamic companies that I have studied have principles in place that reflect the growing acceptance among contemporary Malaysian Muslims that a more orthodox interpretation of sharia for everyday life — that is, one more closely aligned with the Arab core — will guide their behavior at all times, in public and private life. Corporate Islamic culture thus tells Muslims in the workplace how they should dress, act, and interact, stating what is permissible and prohibited in their moral and gendered behaviors. As the sharia interpretations underlying Malaysia’s Islamic family law have become more conservative and male-privileging in recent decades,[9] key assumptions about the role and rights of women at work have followed in turn. Thus, women in the companies I studied had careers, but rarely roles in the boardroom or in top managerial positions. They worked, they told me, only because their husbands allowed them to and in jobs that were most suitable for them: those which gave them the flexibility to fulfill their primary commitment as wives and mothers.

The corporate elites I interviewed — mobile Muslim professionals with global aspirations and networks — believed that Islam and sharia not only provide an ethical and moral template for participating in economic life and the human engagements that emerge from it, but also for organizing and managing the very structures and social relations of corporations. Sharia, as they understood it, grants authority to men, and to leaders, and carries with it notions of verticality and authority. It therefore sat easily alongside and blended with the cultural and managerial premises, practices, and power assumed in contemporary capitalism, with the elite and gendered landscape of global corporate life, and with orthodox premises in Islam. Increasingly, I argue, cosmopolitan, globally sophisticated, financially savvy Malay-Muslim “men of the market and the mosque” practice what they contend are the morals, techniques, and ethics of modern and successful Islamic life; they are Muslims building businesses and banks, not bombs. At the same time, for the ordinary Muslims working under them, and very much for Muslim women, they are in the business of producing a more orthodox Islam in corpORATE mALAYSIA.

[1] Edmund Terence Gomez, Johan Saravanamuttu, and Maznah Mohamad, “Introduction,” in Edmund Terence Gomez, Johan Saravanamuttu, and Maznah Mohamad, Eds., The New Economic Policy in Malaysia. Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013).

[2] See Thomson Reuters, State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2014/15, accessed December 6, 2016, http://www.flandersinvestmentandtrade.com/export/sites/trade/files/news….

[3] Marina Welker, Damani Partridge, and Rebecca Hardin, “Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form: An Introduction,” Current Anthropology 52, S3 (2011): S3–16, 3-4.

[4] Patricia Martinez, “Deconstructing Jihad: Southeast Asian Contexts,” Kumar Ramakrishna and See Seng Tan, Eds., After Bali: The Threat of Terrorism in Southeast Asia (Singapore: World Scientific and the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2003).

[5] Edmund Terence Gomez, Johan Saravanamuttu, and Maznah Mohamad, “Introduction.”

[6] See Kikue Hamayotsu, “Islamisation, Patronage and Political Ascendancy: The Politics and Business of Islam in Malaysia,” Edmund Terence Gomez, Johan Saravanamuttu, and Maznah Mohamad, Eds., The New Economic Policy in Malaysia. Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013) 229-252 .

[7] Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2015, accessed December 6, 2016, http://www.transparency.org/cpi2015.

[8] See Sophie Lemière, “Conversion and Controversy: Reshaping the Boundaries of Malaysian Pluralism,” in Juliana Finucane and R. Michael Feener, Eds., Proselytizing and the Limits of Religious Pluralism in Contemporary Asia (Singapore: Springer, 2014) 41-64.

[9] Maznah Mohamad, “Malaysian Shariah Reforms in Flux: The Changeable National Character of Islamic Marriage,” International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 25, 1 (2011): 46–70.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.