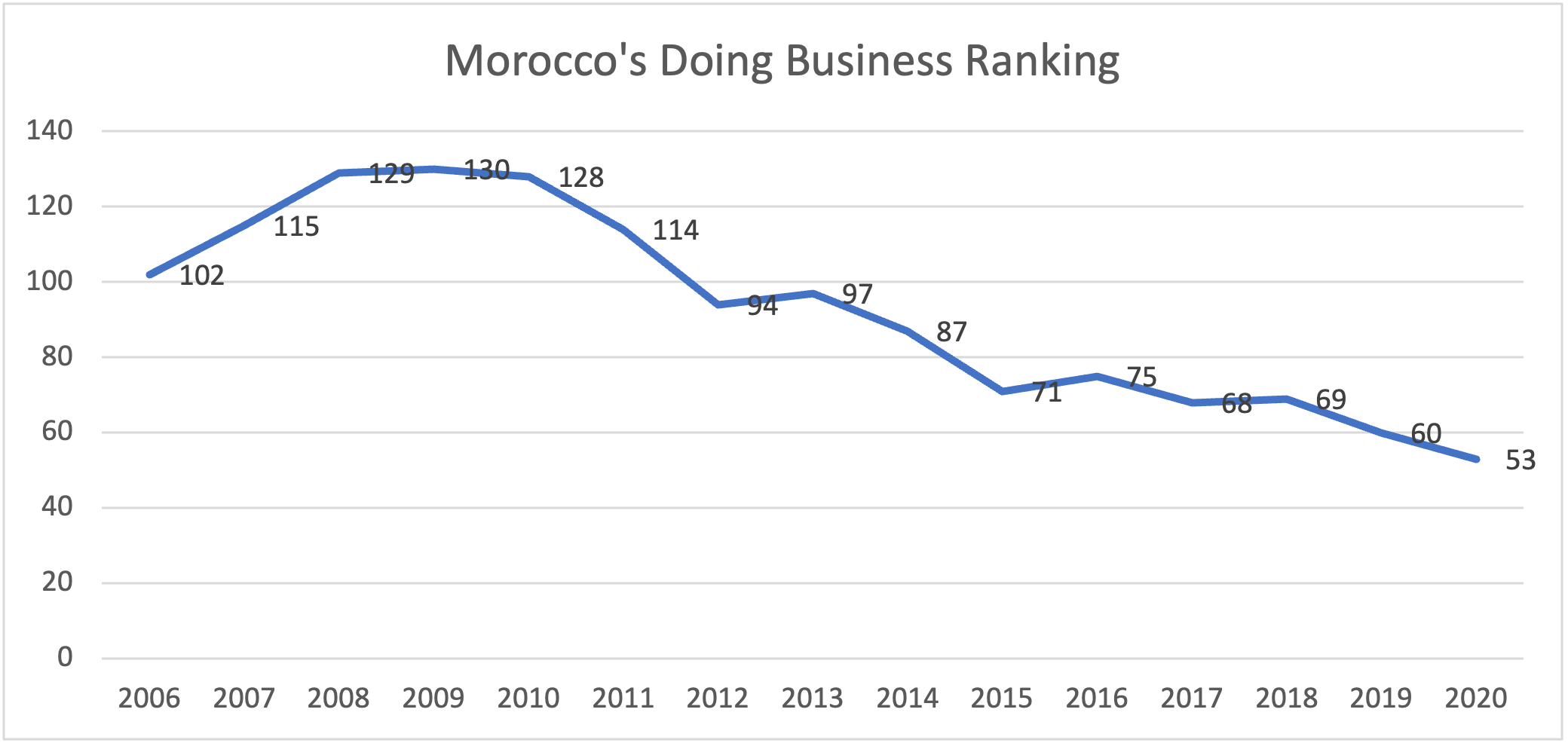

Over the past decade, Morocco made great progress in climbing up the global Doing Business Index (DBI), jumping from the rank of 130 in 2009 to 53 in 2020. The government considers this a resounding success. In 2010, the kingdom established a “National Committee for the Business Environment” (Comité National de l'Environnement des Affaires), whose mission is to offer recommendations and coordinate efforts to improve the country's DBI ranking.

Chaired by the prime minister, the National Committee for the Business Environment brings together ministries and private sector representatives, including members of the General Confederation of Enterprises of Morocco, with the goal of developing the private sector and improving the business climate. The committee’s stated purpose is “to propose and implement measures that might serve the improvement of business climate, strengthen its legal framework, and assess its impact on the relevant sectors.” To this end, it set three priorities: reforming the legal and regulatory framework of business; digitizing and simplifying administrative procedures; and creating a “single-window” customs system.

Over the past decade, the committee successfully advocated for legislative changes to streamline the economy, such as reducing registrations fees for new companies and digitizing procedures for documentation related to construction licenses, imports and exports, tax exemptions, as well as planning information notes. These and other measures have contributed significantly to moving Morocco up the index.

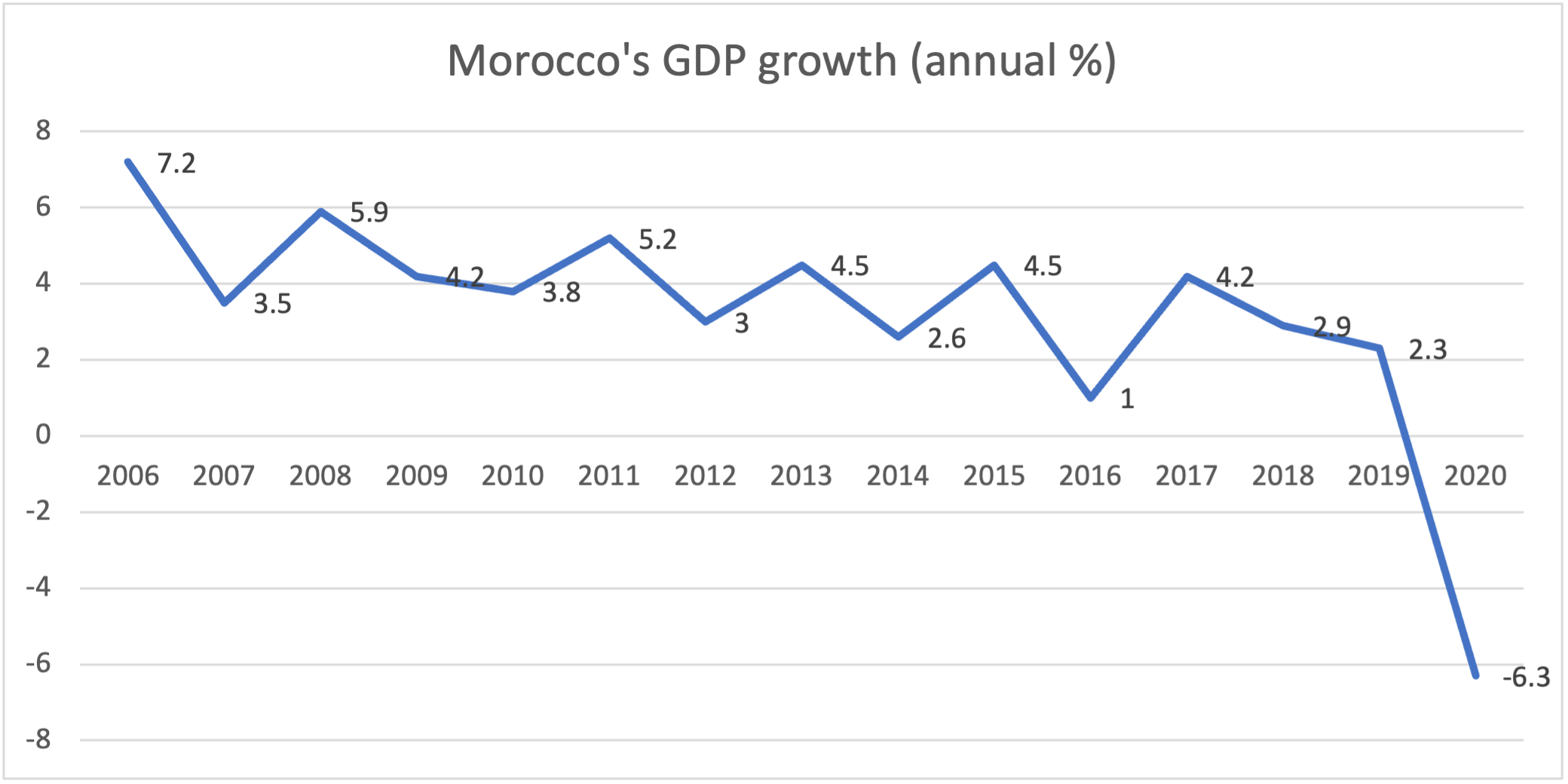

Yet, Morocco’s improved DBI ranking did not correlate with significant economic improvement; the country recorded low rates of economic growth during this period. The average economic growth between 2010 and 2020 was just 3.3%, much lower than what the report’s rave reviews would lead one to expect. In 2016, Morocco achieved an economic growth rate of only 1.06%, even though in the same year its DBI ranking rose from 87 to 71. Notably, since the annual publication of the DBI, Morocco achieved its highest economic growth rate — 7.2% — in 2006, when its ranking was 102.

More than anything, the economic growth rate reflects the state of the private investment market. From 2009 to 2019, private investment growth rates never exceeded 10% and even dipped into the red in 2013, 2014, and 2017, years that saw Morocco rise in the DBI ranking. Despite supposed improvements in the business climate, the private investment market lacked the dynamism to match the report’s plaudits.

In sum, the World Bank’s report on Morocco’s achievements doesn’t match up with the country’s actual economic performance. Such a discrepancy calls into question the credibility of the data adopted by the report. Morocco suffers from structural factors that impede investment, including corruption and low levels of governance, economic freedom, and property rights protection.

After the World Bank discontinued the "Doing Business Report" in September 2021, discussion about the business climate disappeared almost completely in Morocco, and the National Committee for the Business Environment seems to have stopped carrying out its work — the last post on its Facebook page was published on March 2, 2021. This all but confirms that the Moroccan government was more interested in quick legislative fixes that boosted the country’s DBI ranking (and thereby improved its image abroad) than in fundamentally reforming the economy. In recent years, Moroccan officials have not hidden their displeasure over international reports’ statements about their country.

Morocco’s strategy, however, only targeted the DBI’s metrics, while ignoring the metrics assessed by freedom of business rankings from the Canadian Fraser Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and the World Economic Forum (in its "Global Competitiveness Report"). All of these reports, by highlighting weak property rights, high taxes, and restricted investment freedom, painted a less than rosy picture of doing business in Morocco.

Last month, the Heritage Foundation report downgraded Morocco’s rankings for the fifth consecutive year. From 2017 to 2022, the Heritage Foundation lowered its grades for Morocco in several key economic freedoms: “investment” (from 70.0 points out of 100 to 65.0), “business” (from 67.7 to 64.8), and “trade” (from 84.0 to 68.4).

The dysfunction of the Moroccan judicial system is among the most important obstacles to private investment. The effectiveness of the judicial system, according to the Heritage Foundation, declined from 41.9 to 32.7 points between 2017 and 2022. At the 2019 International Conference on Justice in Marrakesh, King Mohammed VI stated, “Providing an appropriate climate for investment requires not only updating legislation but also providing legal and economic guarantees that ensure confidence in the judicial system and provide full security for investors.”

In fact, Morocco’s own reports attest to the fraught business environment. A report by the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council, which is a government institution, revealed that 60.65% of respondents consider doing business in Morocco “very difficult,” while a mere 2.58% said that it is “very easy.” Even in the region of Casablanca-Settat, the capital of business and finance in Morocco, 60% said that doing business is “very difficult.”

Before the World Bank releases its new report to replace the DBI, the National Committee for the Business Environment must take up its work again and present its recommendations. What Morocco needs more than ever is a favorable climate for doing business and real changes on the ground, especially greater protection of property rights and reforms to the judicial system, as well as other institutions. This way, Morocco can boost private investors’ confidence and encourage them to take risks in a context clouded by the consequences of both COVID-19 and 10 years of chaos and instability in the region.

Rachid Aourraz is an economist and co-founder of the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA), as well as a senior analyst. In addition, he is also a non-resident scholar with MEI’s North Africa and Sahel Program. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.