Summary

Despite constituting about 20 percent of the Israeli population, Israel’s Palestinian minority does not wield significant political power; throughout Israeli history Palestinian parties have played the role of the permanent opposition. As a multi-party parliamentary democracy with a relatively low electoral threshold, in theory, Israel would allow for a proportional representation and inclusion of its minority stakeholders. While low Israeli-Palestinian electoral participation and the resulting disproportionate parliamentary representation have hampered political influence, these factors are merely one part of a multi-faceted and multi-causal picture. This report, therefore, seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of the exogenous and endogenous drivers of reduced Palestinian political engagement.

This work is concerned with the structural obstacles –– primarily put in place and sustained by the Israeli right wing –– that seek to impede Palestinian influence at the polls and in the Knesset. It is the existence of these legal and social impediment tactics that, at times, lead to ideological electoral boycotts by members of the Palestinian community. A decrease in the perceived democratic nature of Israel, as evidenced in recent polls, has coincided with feelings of non-influence in a system that enables socio-economic stratification and political disempowerment among the Palestinian minority. Politically-motivated electoral boycotts are also the result of negative perceptions of Palestinian politicians and the public’s awareness of inter-party divisions and parliamentary ineffectiveness. The recent reconstruction of the Joint List, this paper notes, therefore does not necessarily promise a repeat of its 2015 election success. Political differences among the revived list, including over a (hypothetical) collaboration with the Zionist party Kahol Lavan, thus continue to beset the multi-party alliance and reduce voter confidence.

Palestinians in Israel: An indigenous minority

Analysis and news on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict tend to focus on those Palestinians living outside the 1967 borders, in the West Bank, Gaza, and further afield.1 Less attention is given to the Palestinian minority2 living within the 1948 borders, as citizens of Israel, a nation-state which continues to define itself — and its political institutions — based on its Jewish nature.3 The relationship between these Palestinian citizens, the descendants of the individuals who were able to remain in Palestine during the 1948 War, and the state consequently has been an unresolved source of tension and conflict.

Today, most of the Palestinians in Israel live in ethnically homogenous cities and villages (69 percent) across three main regions in Israel: the Galilee in Northern Israel, the “Triangle” area in the country’s center, and in the Naqab in the south.4 In addition, some 10 percent of the population live in mixed cities, such as Jerusalem, Haifa, Lud, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Ramla, and Acre.5 As Arabic speakers and followers of — predominately — (Sunni) Islam,6 Palestinian citizens of Israel constitute both a religious and cultural minority. Yet, this is not an ethnic-migrant-minority; Palestinians in Israel consider themselves indigenous people who are under the rule of a majority that is largely nonindigenous7 and — with that — challenge Jewish claims to the land. At the same time, their assumed identification with and empathy for the larger Palestinian nation — in spite of organizational claims in the West Bank and Gaza8 — are viewed with suspicion and distrust on the part of the dominant Israeli state.9 The resulting socio-economic situation is, as a result, highly paradoxical for the Palestinian minority.10

Palestinians citizens of Israel make up about 1.9 million individuals or 21 percent11 of the population and are allegedly eligible for the same rights, legal protections, and official citizenship status as the predominant Jewish population. Nevertheless, they are considered both a marginalized and discriminated minority.12 As citizens of a Jewish state that recognizes no distinction either between religion and state or between religion and nationality, they are denied national membership, resulting in certain legal ineligibilities, principally concerning immigration and homeownership rights.13 Inequality in government budget allocation, including in education, welfare, health14, and public services in Palestinian localities and mixed cities have compounded socio-economic stratification15 and cultural disempowerment.16

"The political marginalization of Israel’s Palestinians citizens is both multi-faceted and multi-causal, involving political and social deliberations that are variable and differ across the country."

Israel’s multi-party democratic system

Contemporary literature on democratic systems is driven by the ideological assumption that minorities’ political participation promotes proportional representation and social legitimacy.17 Moreover, by providing ethnic minorities with power-sharing abilities, the premise goes, conflict can be moderated through institutional arrangements and procedures as (increased) political participation is deemed effective.18 It follows that, based on this understanding, modern democracies provide channels for individuals to “become masters of their own fate”19 through personal votes and/or participation in electoral campaigns. According to this dictum, a parliament is not only representative of the spectrum of positions held by the populations, but also of the population it represents through a proportional inclusion of relevant subgroups.20

As a multi-party parliamentary democracy with a relatively low electoral threshold, Israel would, in theory, represent the proportional representation system21 that enables maximum influence and inclusion of minority stakeholders. Nevertheless, Zionist parties demonstrate clear dominance within the Israeli political system.22 The political marginalization of Israel’s Palestinians citizens is both multi-faceted and multi-causal, involving political and social deliberations that are variable and differ across the country.23 Thus, electoral turnout in the Triangle, a concentration of Palestinian villages bordering the West Bank, has consistently been higher than in other parts of the country. Beyond the legal impediments and discriminatory practices faced by Palestinian politicians and voters, this report also addresses Palestinians’ representational ability from within the Knesset. Indeed, low electoral turnout rates among the Palestinian population in part derive from an ideological boycott, which questions the ability — and desire — to challenge governmental tactics that create structural obstacles for Palestinian citizens. Polls conducted in recent years show a decline in the perception of Israel’s democratic nature toward Palestinian citizens. In 2012, 44 percent of Palestinian respondents believed that the state was “democratic in the right measure”24; however, by 2018, only 33 percent of respondents claimed that Israel was democratic toward its Palestinian citizens.25

"According to a 2017 report by Adalah, a human rights organization and legal center, the government has over 65 laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel in various sectors ranging from education to property ownership and political participation."

Palestinian political engagement

It took until the 1980s and 1990s for independent Palestinian political parties to develop along ideological and religious lines in the wake of a period that is known as Palestinization.26 This process, which Rami Zeedan describes as “the national awakening of the Arabs in Israel,”27 reflects important political and social events in Israeli and Palestinian society, in addition to the development of self-identification of Palestinians in Israel. In the political context, the process informed a contextualizing of Israeli-Palestinians’ concerns and interest within the wider Arab world. A particularly important turning point in this process occurred in the late 1980s, with the outbreak of the First Intifada (1987-93). This popular uprising, which engulfed the West Bank and Gaza, positioned Palestinian-Israelis on “the periphery of both Palestinian and Israeli societies,”28 and led their leaders to become more involved in international relations with the Arab world and the Israeli-Palestinian peace process of the early 1990s.

Palestinian political parties in Israel, which had been set up in the preceding decade(s), offered important support to the Oslo Accords. As part of a partnership known as the “Block,”29 Hadash (est. 1977) and the Arab Democratic Party, or Mada, (est. 1988), helped approve a new government in 1992, led by Labor leader Yitzhak Rabin.30 In 1995, the Block’s members voted to approve the Oslo Accords, leading the opposition leader at the time, Benjamin Netanyahu, to protest that the accords were approved by a “non-Zionist majority, including five representatives of Arab parties that are affiliated with [the] PLO.”31 Influenced by the buoyancy of the Oslo Accords and an internal political discourse focused on peace,32 Palestinian electoral turnout rose between 1992 and 1999, with Palestinian voters increasingly turning to Palestinian parties, and away from Israeli-Zionist parties.33

Another crucial turning point in Palestinian voting patterns occurred in 2000 with the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Although this uprising, similarly to the previous one, mainly involved the Palestinian Territories, protests were held by Palestinians inside Israel to challenge the heavy-handed Israeli reaction to Palestinian demonstrations inside Israel and violence in the territories. In October 2000, clashes between Palestinian demonstrators and the police led to the death of 13 citizens, fueling the isolation of Palestinian citizens in an increasingly polarized Israeli society.34 The events led to the publication of various reports, including by a commission established in the wake of the clashes, the Orr Commission, and so-called Arab Vision Documents by Palestinian society inside Israel. These documents35 sought to offer recommendations to create a more inclusive society for Israel’s Palestinian minority through comprehensive policy reforms. Published in September 2003, the Orr Commission report ––unsuccessfully –– demanded police reform and prosecution of the police officers involved in the deaths of the Palestinian citizens.36 At the same time, the commission castigated Israeli society for its systematic “prejudice and neglect” of the country’s Palestinian citizens.37

Even before its publication, the Orr Commission’s investigation had a profound effect on the Palestinian community. Witness testimony collected from November 2000 confirmed the indiscriminate usage of violence against Palestinian protestors by Israeli security forces and their failure to offer sufficient protection from violent mobs. The Palestinian community accused the state — led by Labor Prime Minister Ehud Barak — of trivializing their plight; the deep dissatisfaction with the existing political establishment led many in the Palestinian community to feel that there was no real difference between the Israeli right and left.38 For the first time, a consensus was formed among Palestinians in Israel to boycott national elections. In special elections for prime minister held in February 2001,39 turnout rates among Palestinians dropped to an unprecedented low of 18 percent, a clear verdict on Barak’s tenure.40 The failure to bring the police officers to trial, in addition to the general disregard of the report’s final recommendations, remains an open wound for the Palestinian community,41 as evidenced by Barak’s belated apology in July 2019. In response to an op-ed written by Meretz parliament member Esawi Frej titled “Things that Barak Needs to Say,”42 the former Labor party leader apologized for his role in the violent thwarting of the protests in order to pave the way for a merger between his newly-founded Democratic Israel Party and Meretz, a left-wing Israeli party that promotes equality for the state’s minorities.43

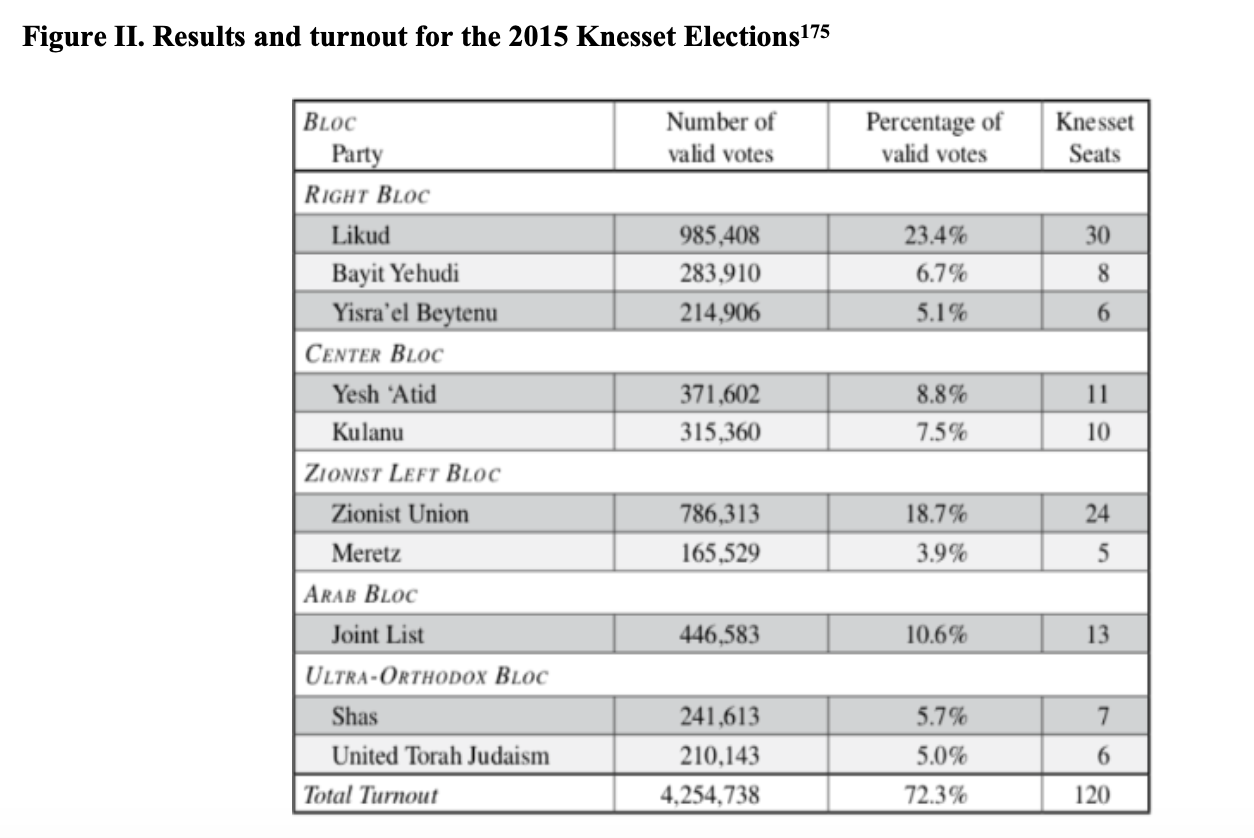

Palestinian voting rates have declined steadily since the beginning of the 21st century. Palestinian turnout, as shown in Figure I, decreased from 77 percent in 1996 to 62 percent in 2003, 53.4 percent in 2009, and 56.5 percent in 2013.44 Despite a brief surge in voter turnout in 2015 to 63.7 percent, with the dissolution of the Joint List (JL), the elections of April 2019 saw a return to the pre-2015 trend. Only 49 percent of eligible Palestinian Israelis45 voted in the April election; a pre-September survey indicated that even fewer plan to vote in the do-over election,46 namely 37 percent.47 While the decline in Palestinian participation in Knesset elections coincided with a decrease in general voter turnout rates across the wider Israeli population,48 it has been sharper and incorporates socio-political motives that are specific to the Palestinian population.49 Indeed, persistent high levels of Palestinian participation in municipal elections, which have remained at around 90 percent for the past three decades,50 demonstrate an ongoing dedication to engagement in local politics.51 During the last local elections, in October 2018, Palestinian turnout was 84.4 percent compared with 54.8 percent among the Jewish electorate.52 The decoupling of local elections from national ones is, as various scholars have argued, premised on familial and clan, or hamula, affiliations53 and a belief in local politicians’ effectiveness and ability to realize quotidian interests.54

The reasons for the distinct patterns of politician participation among Palestinians are, as previously noted, multifaceted. Palestinian engagement in national elections is constricted by wide-ranging Israeli measures seeking to reduce participation through utilizing the legal system, exclusionary political measures, and voter suppression tactics in an attempt to uphold the status quo. The ruling party’s April 2019 attempt to equip officials at ballot stations in Palestinian localities with hidden cameras, for instance, was motivated by a desire to suppress voter turnout in those communities, according to Israel’s Democracy Institute.55 Kaizler Inbar, the public relations firms that carried out the NIS1.5 million ($430,000) operation, boasted of its achievements in the wake of the election, stating that through “deep and close cooperation with the best people in the Likud, we launched an operation that decisively contributed to one of the most important achievements of the national [right-wing] camp — ‘voting integrity’ in the Arab sector. … By placing our observers at every poll, voter participation was lower than 50%, the lowest in recent years.”56 Likud, which is headed by Prime Minister Netanyahu, allocated twice as much funding57 to utilize the same surveillance system during the upcoming September elections in order to prevent what it claims is “massive voting fraud in Arab communities.”58 Following the Central Elections Committee’s (CEC) decision to bar parties from using cameras in August 2019, Likud said it was looking into the possibility of passing legislation to enable polling station representatives to be equipped with cameras on Sept. 17.59

"Palestinian engagement in national elections is constricted by wide-ranging Israeli measures seeking to reduce participation through utilizing the legal system, exclusionary political measures, and voter suppression tactics in an attempt to uphold the status quo."

Palestinian political marginalization

The sustained policy of discrimination and exclusion of Palestinians in Israel, the Israeli scholar Ilan Pappé notes, has curtailed their basic collective and individual human and civil rights.61 These exclusionary measures extend to the political sphere, where Palestinian citizens have –– for the most part –– been forced to resort to being clients of Israeli institutions centered on upholding the dominance of the existing “ethnic democracy.”62 According to a 2017 report by Adalah, a human rights organization and legal center, the government has over 65 laws63 that discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel in various sectors ranging from education to property ownership and political participation.64 One of the most recent laws highlighted by Adalah is the Nation-State Law, which following its parliamentary approval by 62-5565 was legislated in July 2019 as a Basic Law.66 The Nation-State Law constitutionally enshrines the identity of the State of Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people67 by guaranteeing the ethnic-religious character of Israel as exclusively Jewish, and by declaring that “the Jewish people have an exclusive right to national self-determination in Israel.”68

The law’s failure to mention either equality or minority rights, in addition to the downgrade of the status of Arabic from an official language of the State of Israel to a language with “special status,”69 led to significant criticism, including from the Israeli left wing70 and Palestinian parties. In a joint statement, Knesset members (MK) Ahmad Tibi and Yousef Jabareen denounced the bill’s passage as the “last nail in the coffin of the so-called Israeli democracy.”71 The perceived codification of Palestinians’ status “as second-class citizens” in Israel led to calls for an election boycott earlier this year based on what As‘ad Ghanem and Muhannad Mustafa term “feeling[s] of non-influence [due to] the structural obstacles that the ethnic Israeli system erects.”72 Bolstered by Netanyahu’s comments that “Israel is not a state of all its citizens,”73 pro-activists sought to persuade others among Israel’s Palestinian minority not to cast their vote in an attempt to boycott “the body that actively tries to erase our Palestinian identity.”74

Legislation is also, at times, geared toward a system of systematic exclusion of the Palestinian political leadership. As Shourideh Molavi notes, consecutive Israeli governments have employed a variety of legal tools, including criminal investigations and proceedings, as instruments for political suppression.75 The 2002 amendment to the Basic Law has become a particularly important measure in curbing Palestinian representation. Passed in May 2000, Amendment 35 prevents any person from participating as a candidate in Knesset elections if their aims or actions either “explicitly or implicitly” deny or challenge the Jewish and democratic nature of the State of Israel.76 The amendment also points out that “support for an armed struggle of an enemy state or of a terrorist organization against the State of Israel” is grounds for disqualification from the elections.77 According to Molavi, despite the ambiguous nature of terms such as “armed struggle” and “terrorist organization,”78 the legislation is almost exclusively applied to “Arab MKs.”79

Amendment 35 has been utilized several times since its adoption. In 2007, for instance, Israel accused the head of the Balad Party at the time, Azmi Bishara, of abetting Hezbollah during the Second Lebanon War by providing the group with information on locations of strategic targets during the 34-day war.80 Faced with the prospect of a lengthy jail sentence, Bishara left Israel. Despite the publication of secret wire-tapping alleging his complicity, Bishara continues to proclaim his innocence, arguing that the real reason for the accusation is his belief that Israel “should no longer be a Jewish state but must protect Arab rights and become a state for all its citizens.”81 Three years later, in 2010, another MK from the Balad Party, Haneen Zoabi, was penalized for her participation in a Gaza-bound ship as part of the Gaza Freedom Flotilla.82 In addition to curbing her political participation in the Knesset,83 in December 2012, Zoabi was barred from running for the 19th Knesset because of her decision to join the flotilla in 2010.84

Application of the 2002 legislative measure has often gone hand in hand with an amendment passed in 1985, which is aimed at ensuring loyalty to Israel. Section 7A of The Basic Law: The Knesset85 posits that an MK or political party can be prohibited from running in the elections if they demonstrate through their “aims or actions, expressly or by implication ... denial of the existence of the State of Israel as the state of the Jewish people; denial of the democratic nature of the Jewish state; [or an] incitement to racism.”86 Thus, in March 2019, the CEC voted to bar the joint Palestinian party Ra‘am-Balad from the election following a motion filed by Netanyahu’s Likud Party, which claimed that the Balad faction is in favor of eliminating Israel as a Jewish state and, at the same time, backs Palestinian and Lebanese militants –– a decision that was subsequently overturned by Israel’s top court.87 More recently, in the lead-up to Israel’s do-over election in September 2019, Likud teamed up with the far-right Otzma Yehudit88 to ban the JL from running in the upcoming elections in an appeal to the Supreme Court.89 According to the legal bid, the four parties comprising the JL “support Iran and terrorists in jail”90 and “deny […] Israel’s existence as a Jewish state.”91

Questions concerning Palestinians’ loyalty92 and a “national solution”93 to this issue94 have characterized the Israeli state since its inception. Nevertheless, through their legal consideration, they have taken on a more prominent role in the Israeli establishment’s political rhetoric. Members of the Knesset, particularly those belonging to the right wing, continue to question and incite against their Palestinian counterparts who speak critically of Israel while simultaneously demanding proof of loyalty. In the late 2000s, for instance, Yisrael Beiteinu95 campaigned using the slogan “No citizenship without loyalty,”96 a direct reference to ongoing accusations of treason of Palestinian MKs based on perceived anti-Israeli stances97 and collaboration with “the enemy.”98 The electoral platform of the party headed by Avigdor Lieberman also garnered much attention for its call to require those who wish to retain Israeli citizenship to declare their loyalty to Israel as a Jewish state.99 More recently, in early 2019, Netanyahu –– together with right-wing ministers –– ratcheted up his rhetoric with incitement against Palestinian political representatives, claiming that “Arab parties are intent on destroying Israel.”100 The targeting of Palestinian representatives by senior Israeli government officials and other MKs, according to a 2019 Amnesty International report on treatment of Palestinian MKs, is “intended to delegitimize them and their work” through accusations of “treason,” being a “fifth column” or “traitors.”101

The overt questioning of Palestinians’ loyalty has not only been an instrument to curb their political participation, but has equally been used to encourage the Jewish electorate to cast their vote. Netanyahu’s last-ditch effort to rally support in 2015, with the incendiary warning that left-wing NGOs bringing Palestinians “in droves”102 endangered his right-wing government, was aimed to prevent “Arab parties [from] destroying Israel.”103 A similar tactic of “it’s us or them”104 was discerned in early 2019, when the Israeli prime minister sought to expose Benny Gantz and Yair Lapid as “left-wing generals […] relying on Arab parties who not only don't recognize the State of Israel, but want to destroy it.”105 Baited by Netanyahu, the leaders of Kahol Lavan vehemently denied making any deal with “the Arab parties,”106 insinuating that such a deal would be valid grounds for a voter boycott. Rather, in March, Gantz stated that he would work with “anyone Jewish and Zionist,” thereby fully excluding Israeli Palestinians from his political calculus.107

In August 2019, Gantz also ruled out the possibility of including the JL in any future government. In an interview with Channel 12, the former chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces noted that “there are problematic elements”108 in the JL, while MK Yoaz Hendel announced that Kahol Lavan “won’t sit with the Arab parties that basically deny the existence of Israel as a Jewish state.”109 While Kahol Lavan’s stance reflects concerns vis-à-vis Balad members’ acceptance of Israel as a Jewish state, the non-inclusion attitude is in line with the trends among Jewish Israelis; the majority of those polled in 2016 on this topic opposed the incorporation of Palestinian parties in the coalition –– a stance that has been around since 1951, when the leading right-wing opposition party Herut debated against the dependence of an Israeli government on a coalition that was not all-Jewish.110

Despite ongoing voter intimidation practices,111 the curtailment of Palestinian political involvement is not only centered on influencing voter turnout and representatives’ participation. For instance, despite the gradual increase in the number of Palestinian MKs, Palestinian parliamentary influence is limited. Palestinian political representatives have systematically been excluded from influential parliamentary committees, such as the Department of Finance, Foreign Affairs, and Defense.112 As in other arenas of Israeli public and civic life,113 the Supreme Court — the highest court in the country and “celebrated as a force of liberal democracy”114 — has mirrored the societal under-representation. To date, only two male Palestinian justices have served on the 15-member court: Justices Abdel-Rahman Zoabi (1999) and Salim Joubran (2003-17).115

Following the 1977 election, which was characterized by Labor’s transfer of power to the Likud, no Palestinian was part of Israel’s executive branch until 1992. As a result, only in less than half of Israel’s history has there been some Palestinian representation in the executive branch; three Palestinian members of Zionist parties were appointed as ministers and seven MKs were appointed as deputy ministers.116 The average level of representation in the executive branch has been five percent117 –– far below the percentage of Palestinian voters and population in Israeli society. The highest percentage of representation in the executive branch occurred during the above-mentioned Rabin government’s partnership with the “Block,” when ten percent of the ministerial and deputy ministerial positions were held by Palestinians.118 The majority of the Palestinians who have had roles in the executive branch119 were Druze, a Palestinian minority with a unique status in Israeli society, as “a minority within a minority.”120 One such individual, Ayoub Kara, of the ruling Likud Party, served as communication minister between 2017 and 2019. In June 2019, Kara resigned, accusing the Likud Party of “sidelining him due to prejudice against the Druze community.”121

Since the dissolution of the “Arab satellite lists” in the 1970s,122 Palestinian parties have always been part of the minority in the Knesset. Palestinian parties that are anti-Zionist, such as Balad,123 or non-Zionist parties, thus have historically played the role of a “permanent opposition,”124 as they have never been invited to become a part of the parliamentary majority or take part in the government. In part, this position derives from Palestinian parties’ self-declared desire to remain in opposition until an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal is signed and equality is secured for Palestinians in Israel.125 Nevertheless, this issue remains subject to change; a poll in 2016 found that the majority of the Palestinian electorate was in favor of Palestinian parties’ inclusion in the coalition and the executive –– a trend which continues until today. Furthermore, some members of the 2015 JL declared that they would support the formation of a left-wing government by granting an outside vote to the coalition, rather than being part of the government.126 Despite the fact that a new government could have been formed between left-wing parties, left-center, and center parties with a total of a majority of 63 seats in the Knesset, a coalition with JL was not considered.127

"The inability to be politically effective through electoral participation and parliamentary work has reduced the motivation and desire to vote and, at times, led to calls for an electoral boycott."

The Palestinian perspective: Concerns over non-influence

The individual desire to participate in voting, according to Ghanem and Mustafa, amplifies when there is an increase in the sense of one’s ability to influence events. Nevertheless, the abovementioned exclusionary legal and social measures have heightened feelings of alienation toward the state, its institutions, and its symbols.128 The structural obstacles have, in turn, fueled feelings of political non-influence.129 Indeed, polls indicate that levels of mistrust vis-à-vis the Knesset among the Palestinian public have remained high. According to a 2018 poll by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI), 81 percent of Palestinian Israelis130 did not trust the Knesset, a significant rise from 2015, when 63.7 percent indicated mistrust.131

The inability to be politically effective through electoral participation and parliamentary work has reduced the motivation and desire to vote and, at times, led to calls for an electoral boycott. For instance, the Palestinian boycott of the 2006 elections –– in the aftermath of the publication of the Orr Commission’s report –– was considered a protest against the Israeli political system. In the lead-up to the March 2006 elections, the Popular Committee for Elections Boycott,132 a political advocacy movement, thus discussed “the failure of the influence experiment to achieve our daily and national-political rights through the Knesset, and the role of this institution as a source of racial legislation for the ‘Jewish State’ against Palestinian citizens […]” and called for the establishment of a separate Palestinian parliament “in Israel [to] represent our public.”133 In spite of Palestinian politicians’ attempts to persuade Palestinians to vote, the failure to implement the committee’s recommendations intensified the boycott trend; only 56.3 percent of Palestinian Israelis voted for the 17th Knesset in 2006.134

A decade after attempts to disqualify Palestinian lists by the Knesset led to a widespread Palestinian electoral boycott, the CEC once again sought to disqualify Palestinian candidates and parties from the former JL in March 2019.135 The CEC’s decision, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court, fueled existing calls for an electoral boycott. Indeed, the declaration of “an emergency situation,”136 as voiced by Palestinian leaders in Israel in April 2019, followed expectations that half of Israel’s Palestinian population would choose not to vote. In the end, Palestinian voter turnout stood at about 50 percent, a 13 percentage point drop from 2015, and led to a loss of three Knesset seats. While the dissolution of the JL negatively affected the Palestinian electorate,137 feelings of marginalization played a significant role. As Zaha Hassan noted, many Palestinian citizens of Israel believed that voting would “legitimize a government that [with the Nation-State Law] had effectively told them that they were not part of Israeli society.”138 Indeed, pro-boycott activists sought to tap into anger over the 2018 law and, in the words of one protester, “boycott the body that actively tries to erase our Palestinian identity.”139

As indicated in the above statement, electoral boycotts also derive from ideological protests which purport that participation in elections provides legitimacy to the state. This style of political abstention expresses both a political protest against the situation of the Palestinians in Israel and the inability — and unwillingness — of governmental institutions to change this situation.140 The duality of these perceptions is evident in the principles cited by the Popular Committee for Elections Boycott, which appeared for the first time in the 2001 prime ministerial elections. In a statement published in 2006, the committee, which included political movements such as Abnaa al-Balad (Sons of the Land in Arabic) that had promoted election boycotts since the 1990s,141 announced that it “advocates the principle of boycotting the next Knesset elections on a political basis.”142 The committee noted that the “central national principle” that precluded support for “the highest Israeli institution, the Knesset, by voting for it and supporting its legitimacy” derived from this institution’s representation of “the state which was built over the rubble of our people and still practices the daily suppression and persecution of its children.”143 It is evident that the percentage of Palestinian ideological boycotters, which according to Ghanem and Mustafa made up 10 percent of eligible Palestinian voters in the 2000s,144 will be closely intertwined with perceptions of the state. With the 2017 Jewish-Arab Relations Index showing a decline in “the legitimacy of Jews and the state as perceived by Arabs,”145 an increase in Palestinian boycotters during future elections cannot be excluded.

"The overt questioning of Palestinians’ loyalty has not only been an instrument to curb their political participation, but has equally been used to encourage the Jewish electorate to cast their vote."

Leadership fatigue

The degree of parliamentary representation, however, is not the only measure of political success or failure.146 The Palestinian public’s perception of their own leaders offers a further means to analyze voter turnout trends among this indigenous minority. The extent of Palestinian confidence in their political leadership is thus also closely interconnected with voter abstention or electoral boycotts. Indeed, boycott supporters include those who question whether Palestinian politicians in Israel truly serve the interests of the Palestinian population or are dissatisfied with the leadership. According to Khader Sawaed, concerns over Palestinian politicians’ focus on “personal or party interests” rather than the community at large have grown over the past two years in light of inter-party disputes and politicians’ indictment.147

Recent legal scandals include the 2017 sentencing of former Balad MK Basel Ghattas, who was removed from office after being indicted for smuggling cellphones to Palestinian prisoners.148 In 2019, another Balad member, Zoabi, announced her resignation following allegations of corruption in connection with the party’s 2013 election campaign. Israel’s attorney general, Avichai Mandelblit, announced in August 2019 that he intends to indict the prominent Palestinian lawmaker; as many as 35 other Balad members could also face charges for their failure to report campaign funds in the 2013 election.149 Investigative reporting conducted by Haaretz also recently revealed that Balad, which ran with the United Arab List (Ra‘am) during the March election, engaged in an illegal deal with the ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism to gain more power at crucial polling stations.150

Disaffection with Palestinian leaders’ performance is demonstrated in public opinion polls conducted among Palestinian citizens. A study published by Tel Aviv University in March 2019 found that 42 percent of Palestinian Israelis polled thought Palestinian MKs had performed badly while 24 percent rated their performance as “very bad.”151 The lack of trust, in spite of the re-establishment of the JL, will likely continue to plague the Palestinian leadership and voter turnout. Interviews with residents of so-called “Arab towns” conducted by Haaretz in August 2019 found that voters were dissatisfied with the JL’s lack of focus on daily matters concerning Palestinian Israelis.152 Political infighting and policy disagreements have certainly not aided voter confidence. The disintegration of the JL in February –– following a withdrawal by Ta‘al MK Tibi based on political calculations153 –– led to a crisis, resulting in the lowest electoral turnout since 2001. Political differences among the revived JL, which is ideologically divided between Islamists, nationalists, and communists, continue to beset the alliance, as indicated by the prolonged unification process in the summer of 2019.154 JL Chairman Ayman Odeh’s recently-voiced desire to form a government155 with Kahol Lavan also revealed internal political differences –– despite long-standing support among the Palestinian population for such a coalition.156 Thus, members of Odeh’s own Hadash party157 –– and the JL –– rejected such an arrangement, leaving voters to conclude that inter-party disputes still appear to trump national interests.158

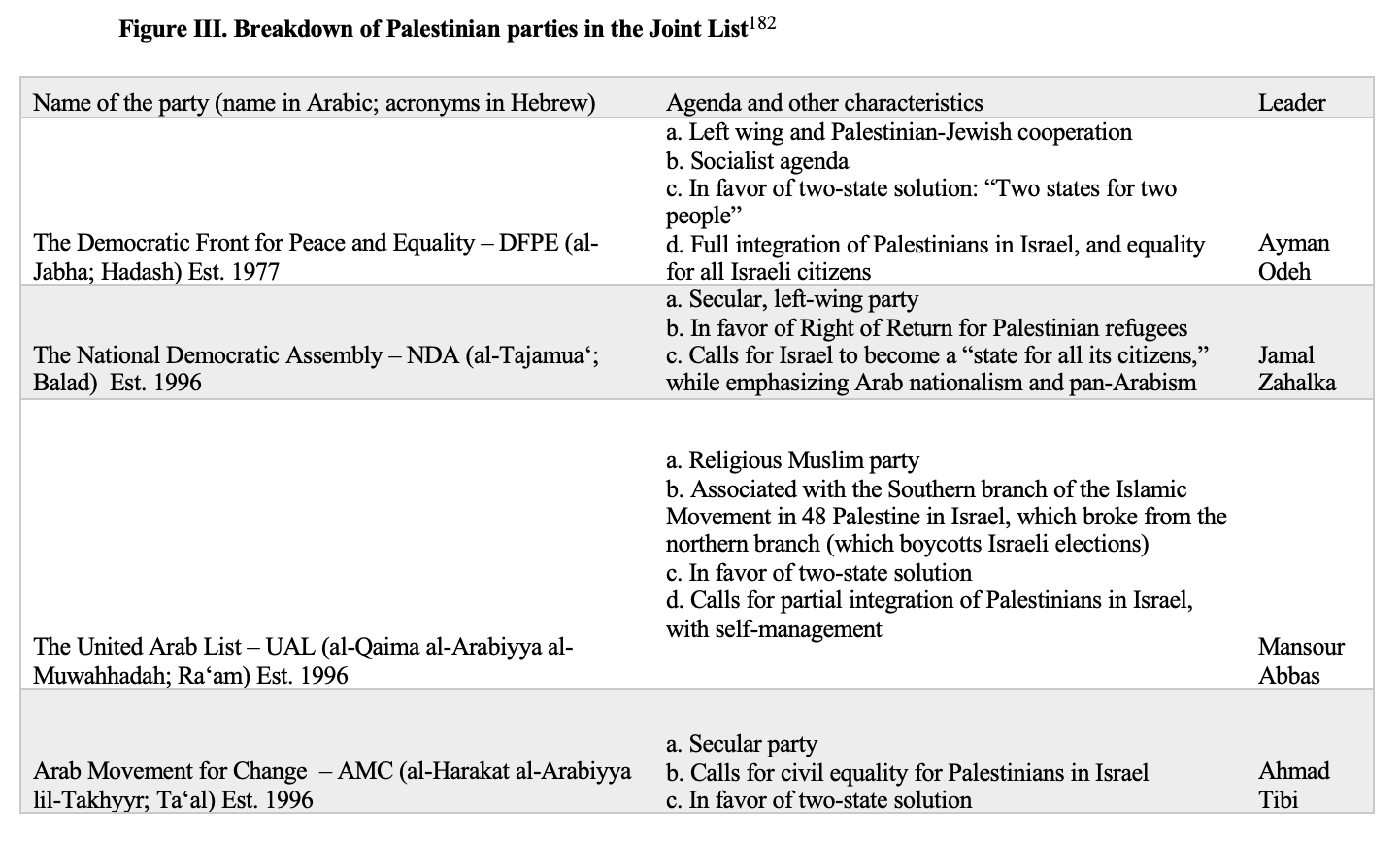

The disappointing results of the April 2019 elections led the former members of the JL to reconsider a joint run for the do-over election in September. In July 2019, Hadash, Ta‘al, Ra‘am, and Balad159 reached a deal to revive the JL in the hope of bringing “down the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu” and replicating the list’s success in the 2015 elections.160 With the election slogan “A Nation’s Will,” the four parties making up the list in 2015 became the third-largest parliamentary faction, winning 13 seats in the Knesset (behind Likud with 30 seats and the Zionist Camp with 24 seats), the largest numbers of seats that main parties representing Palestinian citizens had ever won. Together the Palestinian parties received 444,000 votes, an increase of 27.3 percent compared to 2013,161 and won a greater share of Palestinian votes (83.2 percent) than in any previous election. At the same time, in a process that began in the mid-1990s, Palestinian voters demonstrated reduced support (16.8 percent) for Zionist parties; this has decreased almost 40 percentage points since 1992 (52.3 percent).162

The formation of one Palestinian list for the 2015 elections was preceded by discussions and efforts to reach an agreement to unite.163 Since the mid-2000s,164 polls conducted among the Palestinian population revealed support for political unification; in 2012, a survey by the Palestinian research institute Mada al-Carmel revealed that 76 percent of the respondents supported unification, and this went up to 88 percent in December 2014.165 Two years prior to the elections for the 19th parliament, preliminary negotiations were held by the leaders of Hadash, Balad, and Ta‘al; nevertheless, despite these discussions, the parties’ leadership was unable to reach an agreement to unite. A new law approved by the Knesset in March 2014 with a majority of 67 votes revived unification talks. The 2014 Governance Law, sponsored by the right-wing Yisrael Beiteinu of then Foreign Minister Lieberman, raised the minimum number of votes to earn parliamentary seats from 2 percent to 3.25 percent –– the rough equivalent of four parliamentary seats.166

The declared intention behind the law was to minimize political fragmentation167 and maximize governability. Nevertheless, Zeedan notes that for politicians like Lieberman the purpose was also to minimize Palestinian representation in the Knesset.168 Indeed, although the law was promoted by the coalition as a reform aimed at a strong executive and legislature that would be capable of passing laws,169 it was evident that the raising of the threshold would have far-reaching consequences for the political participation of Palestinian parties, as they would be harder pressed to pass the new threshold.170 Accordingly, the four parties that would make up the list were highly critical of the law. Tibi, head of the Ra‘am-Ta‘al alliance, called the move “anti-democratic,” describing it as “a right-wing initiative” aimed at Palestinian parties and other minorities.171 Bolstered by their constituents’ preference for a unified political platform and a consistent decline in voter turnout, unification was seen as a survival mechanism for Israel’s Palestinian parties.172 After two months of negotiations, the decision was made in January 2015 to establish one united list of candidates; to avoid contention, the JL (al-Qaima al-Mushtarakah in Arabic; ha-Reshimah ha-Meshutefet in Hebrew) agreed that the new merger would not be a party, but a list of candidates only, allowing every member-party to keep –– and promote –– its own agenda.173 Under the leadership of Odeh, the JL members emphasized that the “common national denominator” was stronger than “religious or political affiliations”174 and that, in the past, had created a wide gap between the Islamists of Ra‘am-Ta‘al and the communists of Hadash.

The “politics of faith”176 demonstrated by the Palestinian sector during the 2015 elections coincided with high expectations for the newly-elected Knesset representatives. Campaign efforts, which had concentrated on a ten-year plan to close the gap between Israeli-Palestinians and Israeli-Jews, remained the focus of Palestinian MKs within the Knesset. In December 2015, cooperation between the JL’s leadership and Netanyahu led to the approval of a five-year development plan to increase budgets to the Palestinian sector in Israel.177 Attributed by Odeh to the “ceaseless efforts and pressure of the Palestinians MKs,” the plan allocated an unprecedented amount of NIS15 billion ($4.2 billion) for the years 2016-20 to improve the socio-economic condition of Israel’s Palestinians.178 A study published in 2019 also revealed that around one-quarter of the proposals offered by members of the JL focused on issues of relevance to their constituents, namely cooperation of Palestinian-Jewish relations, wage inequality, and improving the democratic system in Israel.179 The 2018 Parliamentary Work Index for Israel’s Political Parties by the Israel Democracy Institute180 further found that the JL was situated in fifth place (out of ten parties) in overall performance in the Knesset when considering usage of the available parliamentary tools, such as parliamentary queries and speeches. Nevertheless, in terms of the number of bills accepted and participation in plenary votes, the JL ranked lowest, thereby failing to command the quality ranked most important by Palestinians –– getting things done.181

The Palestinian population is mindful of the discrepancies in MKs’ effectiveness. A 2019 survey by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation found that 42 percent of “the Arab public” gave a negative assessment of Palestinian MKs’ performance; 24 percent of these respondents rated their performance as “very poor.”183 The disintegration of the JL in early 2019 did not aid these perceptions. The same survey found that 64 percent of respondents did not believe that a dissolution of the political alliance –– in the form of a JL –– would affect political influence, as “political influence was never pronounced.”184 Those surveyed also viewed the dissolution of the JL as a further sign of “division and lack of coordination and effectiveness.”185 While concerns over political coordination might be stemmed by the resurrection of the JL, the envisioned repeat of the 2015 elections is, as highlighted above, a reductionist wish. Inter-political squabbling over lower slot allocations on the slate186 in July 2019 has revived criticism of the leaders' dedication to the community’s interests187 and offered an unwelcome reminder of the infighting that occurred on the issue of rotation of members on the list, causing deep internal unrest for almost an entire year.188

Absent any significant details of the JL’s post-election plans,189 regaining the faith of the Palestinian community will take a lot of work. Nevertheless, it is evident that Palestinian parties and the Palestinian-Israeli electorate do not hold the sole key to political reform and influence. Discriminatory legal measures that target the Palestinian population in Israel thus both erode the right to equal political participation190 and shrink the ability to wield the available democratic means to pursue an egalitarian and just society. At the same time, the usage of discriminatory and stigmatizing language for political gains reinforces long-held psychological tropes of “the other” while complicating attempts at non-tribalistic politics. Prime Minister Netanyahu’s consistent usage of unfounded, negative narratives against Palestinian parties and MKs, as seen in the run-up to the September 2019 elections, thus legitimizes wrongful accusations and offers an endorsement of social discrimination at the highest level. Confronting the ongoing political divide, as a result, will not only require constitutional reform, but equally demand a profound societal reevaluation.

Endnotes

- Lila Abu-Lughod, “Foreword,” in Displaced at Home: Ethnicity and Gender among Palestinians in Israel, ed. Rhoda Ann Kanaaneh and Isis Nusair (Albany: State of University of New York Press, 2010), ix.

- This work follows recent self-identification trends among the Palestinian population in Israel that favor the designation “Palestinian” over “Arab.” See: Miriam Berger, “Palestinian in Israel,” Foreign Policy, January 18, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/18/palestinian-in-israel/.

- Abu-Lughod, “Foreword,” ix-xiii.

- Rhoda Ann Kanaaneh and Isis Nusair, “Introduction,” in Displaced at Home: Ethnicity and Gender among Palestinians in Israel, ed. Rhoda Ann Kanaaneh, Isis Nusair (Albany: State of University of New York Press, 2010), 9, 10.

- Rami Zeedan, Arab-Palestinian society in the Israeli Political System: Integration versus segregation in the Twenty-First Century (London: Lexington Books, 2019), xvi.

- The vast majority of Palestinian citizens (17.8 percent) are Muslim (with around 80 percent being Sunni), though there is also a small Christian (2 percent) as well as a Druze community (1.6 percent).

- Zeedan, Arab-Palestinian, xxii, xix.

- The PLO and the Palestinian Authority regard Israeli-Palestinians as part of Israel, and they do not incorporate Israeli-Palestinians in their political agenda. Sammy Smooha, Arab-Jewish relations in Israel: Alienation and Rapprochement (USIP: Washington, 2010), 8.

- Smooha, Arab-Jewish,6.

- Shourideh C. Molavi, Stateless Citizenship: The Palestinian-Arab Citizens of Israel (Brill: Leiden, 2013), 2, 3.

- “Population of Israel on the Eve of 2019 - 9.0 Million,” Central Bureau of Statistics, accessed September 1, 2019, https://old.cbs.gov.il/hodaot2018n/11_18_394e.pdf.

- Rebecca Kook, “Representation, minorities and electoral reform: the case of the Palestinian minority in Israel,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40:12 (2017): 2047.

- Eligibility for land ownership and property rights in large portions of the territory of the state, alongside “homeland” immigration rights, for example, are the exclusive rights of Jews. While Netanyahu has claimed that “Arab citizens” have “equal rights,” Adalah has found that the Palestinian community’s exemption from military service has led certain privileges to be refused to Palestinians, including housing and education benefits. At the same time, military service is, at times, considered a prerequisite to gain employment in certain sectors. See: Adalah, The Inequality Report: The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel (Haifa: Adalah, 2011); Jillian Kestler-D’Amours, “Israeli Military Service Requirement Discriminates Against Arab Citizens,” Al-Monitor, May 5, 2013, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/fr/originals/2013/05/israeli-army-service-rights-discrimination.html.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2046.

- Israeli Jews on average earn over 50% more than Palestinian citizens of Israel; half of Palestinian families fall below Israel’s official poverty line. Anonymous, “Israel’s Arab citizens could hold the key to political change,” The Economist, September 7, 2019, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2019/09/07/israels-arab-citizens-could-hold-the-key-to-political-change.

- Kanaaneh and Nusair, “Introduction,” 9/10.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2040.

- As‘ad Ghanem and Muhannad Mustafa, “The Palestinians in Israel and the 2006 Knesset Elections: Political and Ideological Implications of Election Boycott,” Holy Land Studies 6.1 (2007), 51, 52.

- Aviad Rubin, Doron Navot, and As’ad Ghanem, “The 2013 Israeli General Election: Travails of the Former King,” Middle East Journal 68:2 (2014): 248.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2041, 2042.

- Ibid.

- Non-Zionist parties include Palestinian parties, such as Balad, and ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) parties, such as Yahadut HaTora (United Torah Judaism in Hebrew). Maoz Rosenthal, Hani Zubida, and David Nachmias. "Voting locally abstaining nationally: descriptive representation, substantive representation and minority voters’ turnout." Ethnic and Racial Studies 41:9 (2018): 1635.

- Arik Rudnitzky, “Back to the Knesset? Israeli Arab vote in the 20th Knesset elections,” Israel Affairs 22:3-4 (2016): 689.

- “Israeli Public Opinion Polls: Attitudes of Israeli Arabs (2005 - Present),” Jewish Virtual Library, accessed September 1, 2019, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/israeli-attitudes-of-israeli-arabs-005-present.

- Tamar Hermann, Or Anabi, Ella Heller, and Fadi Omar, The Israeli Democracy Index 2018 (Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute, 2018), 70.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2047.

- Rami Zeedan Manuscript Draft, n.d., Arab-Palestinians in the Israeli Political System: Integration vs. Segregation in the 21st Century, Chapter 1: Arabs in the Israeli Three Branches of Power, 7.

- Ibid., 8.

- Palestinian MKs were not officially part of the coalition and did not hold any positions within the executive branch. One of the results of the agreement was the implementation of a five-year plan in 1992 to improve the situation of Palestinian in Israel. Ibid., 23.

- A second occasion that Palestinian MKs made an important difference in the Knesset was in 2005, when Palestinian members of Hadash (DFPE, Democratic Front for Peace and Equality) and Ra‘am (UAL, United Arab List) supported the Israeli disengagement from Gaza in 2005 by giving the minority government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon support in votes of no confidence. Those challenges to the Sharon government were suggested by opponents of the disengagement plan. Ibid., 23, 24.

- Ibid., 23.

- Rudnitzky, “Back,” 694.

- Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 9.

- Molavi, Stateless,13.

- The Arab Vision Documents refer to four documents: The National Committee of the Arab Mayors in Israel, The Future Vision of the Palestinian Arabs in Israel; Adalah – The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, The Democratic Constitution; Sammy Smooha, “Arab-Jewish relations in Israel as a Jewish and democratic state;” Yousef Jabareen, An equal constitution for all: the constitution and collective rights of the Arab citizens of Israel- Position paper. Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 51, 52.

- After five years of investigation and indecision, the attorney general finally resolved in January 2005 to close the case against the police officers on the basis of insufficient evidence. Smooha, Arab-Jewish, 10.

- David B. Green, “The Bloody Events of October 2000 That Just Forced Barak to Apologize to Israel's Arabs,” Haaretz, July 24, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-the-bloody-events-of-october-2000-that-forced-barak-to-apologize-to-israel-s-arabs-1.7569489.

- Yossi Beilin, “What really matters to Israeli Arab voters,” Al-Monitor, September 9, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/08/israel-arabs-joint-list-blue-and-white-police-security.html.

- The 2001 prime ministerial elections, the third and last of its kind, followed the resignation of the incumbent, Barak; all subsequent elections were both for the Knesset and the prime minister.

- Azi Lev-On, “Another flew over the digital divide: internet usage in the Arab-Palestinian sector in Israel during municipal election campaigns,” Israel Affairs, 19:1 (2013): 168.

- Smooha, Arab-Jewish,10.

- Esawi Frej, “Things that Barak Needs to Say,” Haaretz, July 23, 2019, https://www.haaretz.co.il/opinions/.premium-1.7548519. [In Hebrew]

- Afif Abu Much, “Apology of Barak to Israeli Arabs: Political but important,” Al-Monitor, July 25, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/07/israel-ehud-barak-benjamin-netanyahu-apology-elections.html; https://meretz.org.il/about/.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2047.

- Maayan Hoffman, “Survey Finds That As Many As 74% of Arab Israelis Could Vote in September,” The Jerusalem Post, July 30, 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-Elections/Survey-finds-that-as-many-as-74-percent-of-Arab-Israelis-could-vote-in-September-597160.

- After failing to put together a ruling majority after the April elections due to disagreements within Prime Minister Netanyahu’s potential coalition over a draft bill to conscript ultra-Orthodox Jews into the military, Netanyahu forced a re-election in September 2019. It is the first time Israel has held two elections in the same year. See: Miriam Berger, “Why Israel is heading back to elections,” The Washington Post, May 29, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/why-israel-may-be-heading-back-to-elections/2019/05/29/bd9870f2-8233-11e9-933d-7501070ee669_story.html.

- Jerusalem Post Staff, “Only 61% of Israelis Plan on Voting in September Election,” The Jerusalem Post, August 25, 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-Elections/Only-61-percent-of-Israelis-plan….

- Since 1996, the turnout in national elections has declined steadily, falling from around 80 percent in the 1990s to around 63.5 percent in 2006. This trend, according to Aviad Rubin, Doron Navot, and As’ad Ghanem, manifests a feeling of despair and distrust with the government’s conduct among a growing number of Israelis. Rubin, Navot, and Ghanem, “2013,” 253.

- Smooha, Arab-Jewish, 11.

- Lev-On, “Another,” 157.

- Approximately 80 percent of all Palestinian citizens of Israel live within the jurisdiction of Israeli-Palestinian authorities (the others live in unrecognised villages or mixed cities with a Jewish majority). As'ad Ghanem and Muhannad Mustafa, “Arab Local Government in Israel: Partial Modernisation as an Explanatory Variable for Shortages in Management,” Local Government Studies, 35:4 (2009): 458.

- Shibley Telhami, “Will Israel’s Palestinian Arab citizens turn out to vote?,” The Washington Post, March 20, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/20/will-israels-palestinian-arab-citizens-turn-up-vote/?utm_term=.81e05931cc12.

- According to Mustafa, in the municipal elections held in 2003, only 11 mayors and heads of municipal councils were elected based on political party affiliation, while the other 42 elected heads of municipalities were elected based on family affiliation. Muhannad Mustafa, “Municipal Elections Among the Arab-Palestinian Minority in Israel: The Rise of Clan Power and Decline of the Parties,” ed. Elie Rekhess and Sarah Ozacky-Lazar, (Moshe Dayan Center and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2003), 21 [In Hebrew]

- Lev-On, “Another,”158, 159.

- Jacob Magid, “Likud’s election cameras motivated by desire to suppress Arab vote, expert says,” The Times of Israel, August 13, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/likuds-election-cameras-motivated-by-desire-to-suppress-arab-vote-expert-says/.

- Shlomi Eldar, “Netanyahu: The art of Arab vote suppression,” Al-Monitor, September 6, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/09/israel-benjamin-netanyahu-likud-arab-voters-camera-law.html; Kaizler Inbar, “Shhh….Don’t tell anyone,” Facebook, April 10, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/Kaizler.Inbar/photos/a.360404798114400/441952863292926/?type=3&theater. [In Hebrew]

- Jacob Magid, “Likud doubles budget for program placing hidden cameras in Arab polling stations,” The Times of Israel, July 30, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/likud-doubles-budget-for-program-placing-hidden-cameras-in-arab-polling-stations/.

- Magid, “Likud’s.”

- To explain the need for such a bill, Netanyahu spread fake reports stating that the Ra’am-Balad electoral list fraudulently crossed the electoral threshold in April and warning that the upcoming “election is being stolen from us.” Isabel Kershner, “Netanyahu Accuses Rivals of Plotting to ‘Steal’ Israeli Election,” The New York Times, September 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/09/world/middleeast/netanyahu-israel-election-arabs.html; Jacob Magid, “In blow to Likud, elections czar bans parties from filming at polling stations,” The Times of Israel, August 26, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-blow-to-likud-elections-czar-bans-parties-from-filming-at-polling-stations/.

- Adapted from Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 6.

- Ilan Pappé, The Forgotten Palestinians: A History of the Palestinians in Israel (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011), 5, 7.

- Dan Rabinowitz, “The Common Memory of Loss: Political Mobilization among Palestinian Citizens of Israel,” Journal of Anthropological Research 50:1 (1994): 31.

- “Discriminatory Laws in Israel,” Adalah, accessed August 20, 2019, https://www.adalah.org/en/law/index.

- Anonymous, “Five ways Israeli law discriminates against Palestinians,” Al Jazeera, July 19, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/07/ways-israeli-law-discriminates-palestinians-180719120357886.html.

- “Israel's Jewish Nation-State Law,” Adalah, accessed August 20, 2019, https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/9569.

- Israel does not have a constitution and instead has Basic Laws, which serve as guiding principles for the state and the legal system. Only 12 laws of its type have been legislated since the establishment of the state of Israel. Saeb Erekat, “The Israeli Anti-Democratic Legislative Trend: A Palestinian Perspective Erekat,” Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture 23: 4 (2018): 31.

- A review of 1969-2006 election platforms shows that the most prominent is the belief in Israel as a Jewish state. Platforms of both Likud and Labor include statements such as “Israel is designated to be a Jewish state” and references to this purposive component of Israeli national identity appear in all election platforms. Neta Oren, “Israeli identity formation and the Arab–Israeli conflict in election platforms, 1969–2006,” Journal of Peace Research 47:2 (2010): 196.

- Andrew Carey and Oren Liebermann, “Israel passes controversial 'nation-state' bill with no mention of equality or minority rights,” CNN, July 19, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/19/middleeast/israel-nation-state-legislation-intl/index.html.

- “Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State Of The Jewish People,” Knesset, accessed August 20, 2019, https://knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/BasicLawNationState.pdf.

- See, for instance: Gil Hoffman, “Meretz Petitions Court Against Nation-State Law,” The Jerusalem Post, July 31, 2018, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Meretz-petitions-court-against-Nation-State-Law-563826.

- Christopher Brennan, “Israel passes controversial ‘nation state’ law,” NY Daily News, July 19, 2018, https://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/ny-news-israel-law-07192018-story.html

- Ghanem and Mustafa, “Palestinians,” 56.

- Netanyahu was responding to the Israeli actress Rotem Sela, who wrote on Instagram: “And what’s the problem with the Arabs??? Dear God, there are also Arab citizens in this country.” Oliver Holmes, “Benjamin Netanyahu becomes longest-serving Israeli PM,” The Guardian, July 20, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/20/benjamin-netanyahu-becomes-longest-serving-israeli-pm.

- Rami Ayyub, “Israel's Arab minority urged to boycott election over divisive law,” Reuters, April 5, 2019, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-israel-election-arabs/israels-arab-minority-urged-to-boycott-election-over-divisive-law-idUKKCN1RH0JL.

- Molavi, Stateless, 71.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 72.

- Ibid.

- Similarly, a 2019 Amnesty International report on treatment of Palestinian MKs found that the application of disciplinary measures appears “to be discriminatory, since Jewish Israeli MKs do not face similar consequences” for similar behavior. Amnesty International, Elected but Restricted: Shrinking Space For Palestinian Parliamentarians in Israel’s Knesset (Amnesty International, 2019), 14.

- Ori Lewis, “Israel accuses Israeli-Arab ex-lawmaker of treason,” Reuters, May 2, 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL02588730.

- Rory McCarthy, “Wanted, for crimes against the state,” The Guardian, July 24, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jul/24/israel.

- The flotilla, which aimed to challenge the blockage of Gaza, was stopped in international waters by Israeli forces, killing nine on one of the seven boats and wounding over 50.

- Zoabi’s right to have a diplomatic passport was revoked, in addition to her entitlement to financial support should she require legal representation, and her right to visit countries without ties to Israel. Zoabi was also denied the right to contribute to Knesset discussions and vote in parliamentary committees.

- Molavi, Stateless, 77.

- An amendment that was passed in 2016 to The Basic Law: The Knesset also allows the Knesset, to expel elected MKs through a majority vote of their fellow parliamentarians if it has determined that two of the conditions that would have barred a candidate’s participation in elections would apply to the member after his or her election. These conditions are defined as “incitement to racism” and “support for an armed struggle by an enemy state or of a terrorist organization against the State of Israel.” Amnesty International, Elected, 11.

- On April 1, 2009, another amendment was proposed to The Basic Law: The Government Loyalty Oath which posits that upon taking up a ministerial office, all ministers must make a loyalty oath to the state as a “Jewish, Zionist and democratic state” and to the values and symbols of the state. Prior to this amendment, ministers were only required to pledge an oath to the state. Ibid., 72, 73.

- Anonymous, “Israel's top court overturns ban on Arab party, disqualifies far-rightist,” Daily Sabah, March 17, 2019, https://www.dailysabah.com/mideast/2019/03/17/israels-top-court-overturns-ban-on-arab-party-disqualifies-far-rightist.

- Otzma Yehudit’s former No. 1, Michael Ben Ari, was barred from running in the April elections by the Supreme Court under anti-racism laws, and was replaced at the party’s helm by Ben Gvir.

- Times of Israel Staff, “High Court hears petitions against Otzma Yehudit, Arab parties,” The Times of Israel, August 22, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/high-court-hears-petitions-against-otzma-yehudit-arab-parties/.

- Jeremy Sharon, “Far Right Otzma, Likud File Appeal Demanding Arab Parties Be Disqualified,” The Jerusalem Post, August 20, 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Far-right-Otzma-Likud-file-appeal-dem….

- Times of Israel Staff, “Likud joins far-right appeal to bar Arab parties from running in election,” The Times of Israel, August 20, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/likud-joins-far-right-appeal-to-bar-arab-parties-from-running-in-election/.

- These concerns are evidenced in recent polls. For instance, a 2018 found that 59 percent of self-identified right-wing Israelis believe that “Israel’s Arab citizens pose a threat to the country’s security.” Among national-religious and Haredi Jews, this percentage goes up to 60 and 70 percent respectively. A 2017 survey by the Israel Democracy Institute also found that 56 percent of Jews think that “most Arab citizens support” the 2017 Temple Mount attacks, which targeted Israeli border police officers. “Hermann, Anabi, Heller, and Omar, Israeli,146; “Survey: 56% of Jews Think Most Arab Citizens Support Temple Mount Attack,” The Israel Democracy Institute, accessed August 20, 2019, https://en.idi.org.il/articles/17558.

- Loveday Morris, “Arab Israeli candidates launch last-ditch effort against Netanyahu and voter disillusionment,” The Washington Post, April 7, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/arab-israeli-candidates-launch-last-ditch-effort-against-netanyahu-and-voter-disillusionment/2019/04/07/ec3efe52-570a-11e9-aa83-504f086bf5d6_story.html?utm_term=.530d1b247c88.

- In 2010, the Israeli minister of foreign affairs, Avigdor Lieberman, expressed his desire, including during a speech to the UN General Assembly in 2010, to transfer the Palestinians to a Palestinian “Bantustan” –– based on the notion of a transfer –– in the West Bank in return for annexation of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank to Israel. Pappé, Forgotten, 6.

- “There is no citizenship without loyalty,” said Israeli MK David Rotem (Yisrael Beiteinu), who proposed the bill, which passed its final reading in a vote of 37-11 in Israel’s parliament in 2011 and found its origin in Lieberman’s “no loyalty, no citizenship” campaign in 2009. The amendment to the Citizenship Law of 1952 allows the Supreme Court to “revoke citizenship, in addition to issuing prison sentences, against people who are convicted of treason, serious treason, aiding the enemy in a time of war, or having committed terror against the state.” For other loyalty-citizenship laws and proposals, see: Jonathan Lis, “’Loyalty-citizenship’ Laws,” Haaretz, November 17, 2017, https://www.haaretz.com/1.5210661; Anonymous, “Israel passes law revoking citizenship for spying,” BBC, March 29, 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12897456.

- In 2009, the slogan was hurled at Shas. Just like Israel's Palestinians, most members of the ultra-Orthodox Sephardi community which Shas represents do not serve in the army. Yisrael Beiteinu thus questions their loyalty and right to citizenship.

- Smooha, Arab-Jewish,11.

- Ron Gerlitz, “The Real Reason for Netanyahu's Ferocious Attacks on Israel's Arab Citizens,” Haaretz, February 25, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-the-real-reason-for-netany….

- Kanaaneh and Isis Nusair, “Introduction,” 16.

- Gerlitz, “The.”

- Amnesty International, Elected, 16.

- Mairav Zonszein, “Binyamin Netanyahu: 'Arab voters are heading to the polling stations in droves,” The Guardian, March 17, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/17/binyamin-netanyahu-israel-arab-election.

- Gerlitz, “The.”

- “Bibi or Tibi” also became a rallying cry for Netanyahu during the April 2019 elections. Recycled from the 1996 elections, the chant referred to Ahmad Tibi, head of Ta‘al and sought to highlight his opposition’s willingness to form a government with “Arab parties.” See: Evan Gottesman, “Israel’s Arab Parties Aren’t All the Same,” Foreign Policy, April 3, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/04/03/israels-arab-parties-arent-all-the-same-hadash-taal-balad-ayman-odeh-ahmad-tibi-netanyahu-gantz-lapid/.

- Haaretz, “Netanyahu Blasts Gantz-Lapid Alliance: They Rely on Arab Parties Intent on Destroying Israel,” Haaretz, February 21, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/elections/netanyahu-blasts-gantz-lapid-they-rely-on-arab-parties-who-want-to-destroy-israel-1.6958943.

- Ayman Sikseck, “Why Israel's Arabs stayed away on Election Day,” Ynet News, April 12, 2019, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5492400,00.html.

- Raoul Wootliff, “Gantz: We’re willing to sit in government with ‘anyone Jewish and Zionist,” The Times of Israel, March 11, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/gantz-were-willing-to-sit-in-government-with-anyone-jewish-and-zionist/.

- Jonathan Lis, “Joint List Says It Doesn't Outright Reject Joining Government After Arab Israeli Leader's Overture,” Haaretz, August 24, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/elections/.premium-joint-list-says-it-doesn-t-reject-joining-government-after-ayman-odeh-s-overture-1.7737309.

- Ravit Hecht, “Israeli Arabs Want In, Center-left Says No,” Haaretz, August 23, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-israeli-arabs-want-in-center-left-says-no-1.7733504.

- Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 22, 23, 32.

- The Likud Party doubled its budget for a surveillance operation targeting balloting stations in Palestinian towns on election day in September. Meretz MK Tamar Zandberg wrote that “it is clear to everyone that this is a voter suppression project by the ruling party targeting a public whose turnout rate it views as a major political threat.” Magid, “Likud.”

- Molavi, Stateless, 63.

- Governmental efforts introduced during the Olmert government (2006-09) to include more Palestinians in the public sector have garnered some success; nevertheless, the goal of 10 percent was only met four year after its deadline, in 2016, and it does not constitute a proportional representation of the Palestinian population. Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 34, 35.

- Molavi, Stateless, 64.

- Ibid., 65.

- Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 30.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 31.

- Economically and ethnically, Israeli Druze are part of the Muslim disadvantaged group; yet, culturally, the Druze maintain a singular national position in Israel, in part due to their service in the Israeli army. Druze also tend to vote and participate in Zionist parties. Rosenthal, Zubida, and Nachmias, “Voting,” 1640; Maoz Rosenthal, Hani Zubida, and David Nachmias, “Voting locally abstaining nationally: descriptive representation, substantive representation and minority voters’ turnout,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41:9 (2018): 1640.

- Michael Bachner, “Likud minister quits, accusing ruling party of prejudice against Druze,” The Times of Israel, June 24, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/likud-minister-quits-accusing-ruling-party-of-prejudice-against-druze/.

- As Ben Mendales explains, for the first 28 years of Israel’s existence, the Palestinian minority was represented in the Knesset by a series of “satellite lists,” which were mainly affiliated with the Mapai party and later with the Alignment (which merged into what is now the Labor Party). Ben Mendales, “A house of cards: the Arab satellite lists in Israel, 1949–77,” Israel Affairs, 24:3 (2018): 442-459.

- Ra‘am-Balad, a mix of Islamist and Arab nationalists, which ran as an alliance in April, described itself as a democratic movement opposed to Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory. “We have a fierce argument with Zionism,” Ra‘am head Mansour Abbas stated. Dan Williams, “Far-rightists cleared for Israel election, Arab party blocked,” Reuters, March 7, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-election-candidates/far-rightists-cleared-for-israel-election-arab-party-blocked-idUSKCN1QO111.

- Molavi, Stateless, 63; Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 31.

- Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 31.

- Ibid., 31.

- Second, Palestinian party leaders rejected creating an alliance with leftist parties because of a lack of trust. That is what happened in 2015, when the Joint List as a whole refused to sign a vote-sharing agreement with the leftist Meretz party, thereby hurting the left block electorally and damaging the prospect of an Palestinian-Jewish left alliance. Ibid.,32.

- Ghanem and Mustafa, “Palestinians,” 55.

- Ibid., 56.

- Lahav Harkov, “The Knesset at Age 69: Still Struggling for the Public's Trust,” The Israel Democracy Institute, January 30, 2019, https://en.idi.org.il/articles/20663.

- Rudnitzky, “Back,” 694.

- The 2001 prime ministerial election witnessed the emergence of the committee, a direct response to the October 2000 events. The committee has appeared in every Knesset election ever since. It comprises movements such as Abnaa al-Balad as well as academic, public and media personalities in Palestinian society in Israel. See: Marcelo Svirsky, After Israel: Towards Cultural Transformation (London: Zed Books, 2014).

- Ghanem and Mustafa, “Palestinians,” 51–57.

- Karin Tamar Schafferman, “Participation, Abstention and Boycott: Trends in Arab Voter Turnout in Israeli Elections,” The Israel Democracy Institute, April 21, 2009, https://en.idi.org.il/articles/7116.

- Jonathan Lis and Jack Khoury, “Israeli Arab Slate, Far-left Candidate Banned From Election Hours After Kahanist Leader Allowed to Run,” Haaretz, March 7, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/elections/.premium-far-left-lawmaker-banned-from-israeli-election-for-supporting-terror-1.6999656.

- Anonymous, “Despite calls to boycott 'Zionist' election, Arab voter turnout surges in final hours,” Israel Hayom, April 10, 2019, https://www.israelhayom.com/2019/04/10/despite-calls-to-boycott-zionist-election-arab-voter-turnout-surges-in-final-hours/.

- Daoud Kuttab, “Why was Arab voter turnout so low in Israel’s elections?,” Al-Monitor, April 12, 2019,

https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/04/arab-citizens-of-israel-low-turnout-in-knesset-election-2019.html. - Michael Young, “What the Other Side Thought,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 11, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/78853?lang=en.

- Anonymous, “Israel’s Arab minority urged to boycott election over divisive law,” Al Arabiya, April 5, 2019, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2019/04/05/Israel-s-Arab-minority-urged-to-boycott-election-over-divisive-law.html.

- Ghanem and Mustafa, “Palestinians,” 59.

- In the 1990s the Abnaa al-Balad movement began organizing calls to boycott the Knesset elections in response to Israel’s military attacks in Southern Lebanon.

- Ghanem and Mustafa, “Palestinians,” 62.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 59.

- “Arab-Jewish Relations Index, Directed by Prof. Sammy Smooha of the University of Haifa: Attitudes of Jewish and Arab public concerning coexistence deteriorate, but foundation of relationships is still firm,” University of Haifa, accessed September 1, 2019, https://www.haifa.ac.il/index.php/en/about-top-blue-3/2013-07-01-13-28-00/2934-arab-jewish-relations-index-directed-by-prof-sammy-smooha-of-the-university-of-haifa-attitudes-of-jewish-and-arab-public-concerning-coexistence-deteriorate-but-foundation-of-relationships-is-still-firm.html.

- Zeedan Manuscript Draft, 21.

- Khader Sawaed, “The Arab Minority in Israel and the Knesset Elections,” The Washington Institute For Near East Policy, Fikra Forum, April 9, 2019, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/fikraforum/view/the-arab-minority-in-israel-and-the-knesset-elections.

- Eliyahu Kamisher, “Former MK Basel Ghattas To Enter Prison For Phone Smuggling Affair,” The Jerusalem Post, July 2, 2017, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Former-MK-Basel-Ghattas-to-enter-prison-for-phone-smuggling-affair-498520

- Anonymous, “Prominent Arab-Israeli lawmaker Zoabi to be indicted for corruption,” Middle East Monitor, August 8, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190808-prominent-arab-israeli-lawmaker-zoabi-to-be-indicted-for-corruption/.

- Sivan Klingbail, Chaim Levinson, Yotam Berger, Jonathan Lis, Hagar Shezaf, Nitzan Livne, and Michal Aharon, “Ultra-Orthodox and Arab Parties Struck Illegal Deal at Polling Stations, Haaretz Investigation Finds,” Haaretz, August 14, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-ultra-orthodox-arab-partie….

- Sawaed, “Arab.”

- Yasmine Bakria, “Arab Israelis Are Having a Crisis of Confidence — and It May Keep Them Away From Ballot on Election Day,” Haaretz, August 25, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/elections/.premium-israeli-arabs-ex….

- Meron Rapoport, “Ahmad Tibi has a plan to unseat Netanyahu, but it means leaving his Palestinian partners,” +972 Magazine, January 22, 2019, https://972mag.com/ahmed-tibi-has-a-plan-to-unseat-netanyahu-but-it-means-leaving-his-palestinian-partners/139757/.

- Ben White, “How will the Joint List fare in Israel's snap election?,” Al Jazeera, August 27, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/08/joint-list-fare-israel-snap-election-190823151315950.html.

- Prior to the April 2019 elections, Odeh also called for a united front to oust Netanyahu, naming certain conditions for backing Gantz’ candidacy: support for peace negotiations, equality for Palestinian citizens of Israel, and repeal of the nation-state law. See: Ayman Odeh, “Netanyahu Opens the Doors of Power to Extremists,” The New York Times, March 8, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/08/opinion/israel-election.html; Adam Rasgon, “Ayman Odeh sets out terms for helping Gantz’s Blue and White defeat Netanyahu,” The Times of Israel, March 11, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/ayman-odeh-sets-out-terms-for-helping-gantzs-blue-and-white-defeat-netanyahu/?fbclid=IwAR1TR8UX9vRul7mcCuZqnvwf5gg1DI0itVdtcoDLyih3UQMRPY6oUXDWHmQ.

- Maariv Online, “Poll: 78% of Israeli Arabs Support The Joint List entering Coalition,” The Jerusalem Post, August 27, 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-Elections/Poll-78-percent-of-Israeli-Arabs-support-the-Joint-List-entering-coalition-599769; Times of Israel Staff, “Poll: 73% of Arab Israelis favor joining coalition; voter turnout on the rise,” The Times of Israel, March 21, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/poll-73-of-arab-israelis-favor-joining-coalition-voter-turnout-on-the-rise/.

- MK Aida Touma-Sliman, number two in the Hadash party, for instance, tweeted: “We will not sit in a government of occupation, wars and racism. Our terms do not exist in the current political map.” Other Palestinian lawmakers have indicated they would refuse to serve as ministers as part of the government, but would welcome the opportunity to head powerful coalition-led parliamentary committees that oversee budgets crucial to their sector’s interests. AP and Times of Israel Staff, “Joint List leader hopes to transform Arab role in Israeli politics,” The Times of Israel, August 30, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/joint-list-leader-hopes-to-transform-arab… Feldstein, “Israel’s Election Do Over – An Arab Minority View,” Breaking Israel News, August 27, 2019, https://www.breakingisraelnews.com/136076/israels-election-do-over-an-arab-minority-view-opinion/.

- White, “How.”

- A day after the three Palestinian-majority factions announced that they would run together on a single slate, Balad joined the list. Adam Rasgon, “Nationalist Balad party announces it will run on Joint Arab List in elections,” The Times of Israel, July 29, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/nationalist-balad-party-announces-it-will-run-on-joint-list-in-autumn-elections/.

- Times of Israel Staff, “Three Arab parties agree on joint Knesset run; Balad expected to decide Sunday,” The Times of Israel, July 27, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/arab-parties-said-to-reach-deal-to-revive-joint-list/.

- Doron Navot, Aviad Rubin, and As’ad Ghanem, “The 2015 Israeli General Election: The Triumph of Jewish Skepticism, the Emergence of Arab Faith,” The Middle East Journal 71:2 (2017): 267.

- Rudnitzky, “Back,” 685/6.

- Kook, “Representation,” 2049.