It has been a little over a year since the UAE and Israel inked their historic Abraham Accords. Separately from those accords, much has changed in the global political climate in which their geostrategic alliance and burgeoning trade relationship is unfolding.

The accords have barely affected day-to-day life in either country, just as the Camp David Accords in 1978 did not send cultural shock waves through either Egyptian or Israeli society at the time. Nonetheless, small changes are afoot and the region is globalizing rapidly through key nodes like Dubai and Tel Aviv, where one sees signifiers of this socio-cultural change.

Thus, on my trip to Dubai in September, I shouldn’t have been surprised to see packaged Arabic sweets with a sticker certifying them as “Kosher, Dairy” or a Modern Orthodox Jewish couple (the man wearing a suit and a yarmulka and the woman a flowing white dress) celebrating the end of Shabbat in a high-end hotel lobby near the Jabal Ali district.

These visual signifiers remind us that person-to-person, government-to-government, and business-to-business contacts were likely always happening behind the scenes, but are now relatively out in the open. Unsurprisingly, there is still some hesitance, skittishness, and outright protest that is bound to surface in this human and geopolitical drama. For instance, many Levantine Arabs resident in the Emirates do not wish to be associated with events that have Israeli participants.

But despite a desire by some to bury their head in the sand, seeds are being planted, and even if some are starved of water and do not sprout, others will take hold. If we step back and imagine how these seedlings might grow and flourish over time, we can divine a possible trajectory for the future of the Middle East.

The region is rapidly globalizing and major international trends are emerging within it, some fostering order and others disorder. The region is not only a chessboard for competing external powers, but also home to actors who are shaping cutting-edge global trends, especially outside the political realm.

The Middle East now hosts world-class cultural, culinary, educational, and artistic fusions of every sort. This new Middle East shows that it is impossible to keep people apart and divide them by race, creed, or exclusive nationalisms, as most people are fundamentally uninterested in politics. Rather, they care primarily about their own lives, passions, and friendships. Games, sports, and pastimes bring people together and provide vehicles for such connections.

***

All of these intangible dynamics were on display at the 2021 Oasis Backgammon Championship, the first major international backgammon tournament to be hosted in the Arab World in recent memory. Its timing was not primarily the result of larger geopolitical trends, but in a way a mirror of them.

Three things had fallen into place:

- The landmark recognition by the Emirati authorities of “Tournament Backgammon” as a mind sport and not a form of gambling. In a way, this mirrors the Abraham Accords themselves as a domain in which the UAE authorities are forward thinking, able to buck regional opposition, and keen to get out in front of trends, rather than being passively swept along by them as other regional governments are;

- The Emirati authorities’ decision to lift COVID travel restrictions more comprehensively than other major global destinations, while maintaining transport connectivity and spare accommodation capacity. This makes Dubai a better venue for an international event than other global hubs. This dynamic is mirrored by the current success of the rescheduled 2020 Dubai Expo;

- Dubai is now seen as an important enough high-end tourist destination to secure a prominent slot in the international backgammon calendar’s increasingly busy slate of major events.

With all those boxes ticked, the 2021 Oasis Championship was very much like any other top-tier global backgammon event. It featured the same old faces of the top professionals, committed hobbyists, well-heeled retirees, and the self-employed class who frequent the popular backgammon haunts from Copenhagen and Monaco to Cyprus and New York. The tournament was devoid of Emirati nationals as participants, despite the ministry’s approval, because the tournament backgammon scene is still unknown in the Gulf; however, UAE-based members of the Lebanese, Iraqi, and Syrian diasporas were joined by scores of players from the game’s traditional heartlands: the Southern Caucasus region, Turkey, Iran, Israel, and Russia.

As a frequent participant in international backgammon tournaments, I was surprised by how familiar the aesthetics of the Dubai tournament were. The tournament hotel, ballroom, boards, tournament staff, and draw sheets were interchangeable with those in Europe or even Michigan. Ditto for the participants’ attire, age, and gender demographics. Despite this feeling of “sameness,” the tournament was enhanced by some regional aesthetic flourishes. These aesthetic features are symbolically relevant as they showcase the ways in which the Middle East is becoming similar to everywhere else as it globalizes, while still retaining some local particularity.

The shared Middle Eastern aesthetics of backgammon have made it a regional cultural melting pot. For decades now, Iranians, Israelis, Lebanese, Armenians, Turks, and American Jews have all been playing backgammon together at tournaments in Cyprus, London, and Monaco. I spoke to an African-American woman who has been a stalwart on the tournament backgammon scene for 40 years. She said that to her knowledge an Iranian player has never refused to play with an Israeli player — as happens when governments are dictating cultural norms, like in the Olympics. Only once in her life, in the late 1980s, did a white South African refuse to play with her in Monaco. She believes that might have been the only time that race, religion, nationality, or political creed prevented a scheduled tournament match from transpiring.

The cultural fusion and tolerance at the Dubai tournament was in no way novel, but merely represented the formal codification of broader historical trends, just as covert governmental, person-to-person, and business dealings had occurred between Israel and its Gulf neighbors prior to the Abraham Accords. That said, humans are always afraid of what others might think, and some Levantine players made comments to me along the lines of: “Don’t mention in your article that there are Israelis at this event. I mean, personally, I don’t mind playing with Israeli players and I have a few Jewish friends, but I wouldn’t want to be listed as at an event with Israelis, as other people and the Lebanese intelligence services just won’t understand.” I see this as progress: Saying “I don’t want to play backgammon with a Jew” is no longer politically correct, even for an Iranian or Lebanese Shi’a, but the overall regional climate of surveillance still makes people feel potentially “exposed” to be seen doing anything publicly with Israelis.

Even this skittishness represents a trendline, because 20 years ago there would have been overt prejudice and hostility. On certain human-to-human levels, vast swaths of humanity are no longer differentiated by their regional cultural habits, since many now share a globalized culture. People are no longer fussed about playing backgammon with someone of a different skin tone, religion, or nationality; they do so online all the time. This is especially true for committed hobbyists — myself included — who often have more in common with their fellow amateurs of different nationalities than they do with their own countrymen.

The Dubai backgammon tournament was, therefore, a great metaphor for all the drama and humor of this process of cultural fusion, appropriation, innovation, happenstance, and renewal.

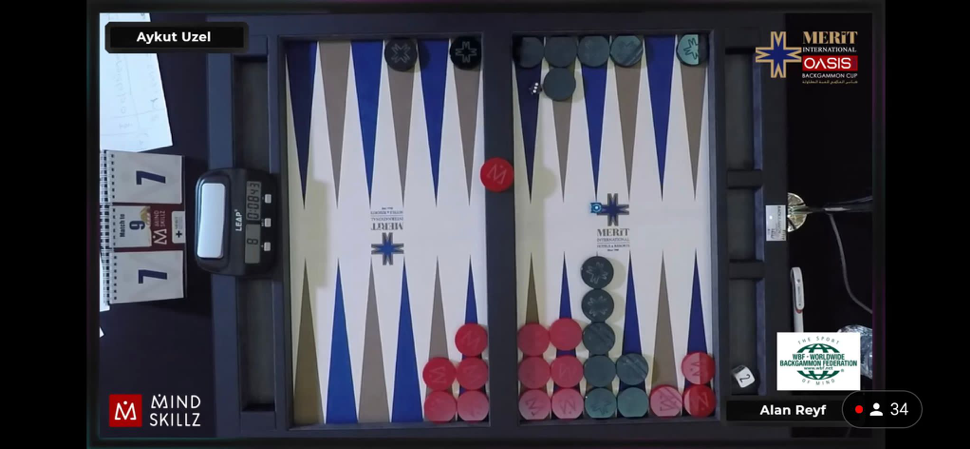

This glorious interplay was on full display in the final match of the Double Elimination Master’s segment of the championship. I had the honor of commentating it for the international audience tuning in to the live stream. As it played out, the final went to a decisive match (i.e. the second chance finalist defeated the undefeated finalist in the first match); then the decisive nine-point match went to a decisive game (called double match point); then that game might have been the longest and craziest I have ever seen (in terms of dramatic reversals, wild dice, major conceptual errors, and deft table feel); finally, despite one participant having achieved an over 97% advantage at one point, the match was decided by the very last roll of the dice. Backgammon is rife with wildly improbably outcomes, yet the final game of this Dubai tournament was truly a once in a lifetime event.

It contained all the wild swings of fortune of a Greek tragedy, combined with the throwback strategies of Middle Eastern nargile café-style cubeless Sheshbesh, yet it was played in the finals of a major tournament on the World Backgammon Federation tour by a seasoned professional tournament player pitted against a successful gentleman hobbyist. Its aesthetics encapsulated everything that is glorious about the contemporary Middle East in general and Dubai in particular. The winner of the tournament, the professional Turkish player Aykut Uzel, crafted a piece of “performance art” blending contemporary neural net-inspired backgammon logic with various throwback strategies emanating from his region. He has always been known on the circuit for his flair and showmanship.

His opponent, Alan Reyf, an America Jew from Florida who had grown up in the former USSR, performed gracefully under pressure. He had heroically come from behind on multiple occasions and made some solid attacking plays. His sterling etiquette and easy-going attitude were commented on by many. Then, as the five-plus-hour final wore on, he seemed to tire, possibly due to jetlag and the cumulative wear and tear of so many high-pressure, high-stakes decisions. To my eyes, in the final game he was slightly overmatched by the Middle Eastern craftiness of Aykut’s game, which pushed Alan out of his comfort zone.

An interview with the winner: Aykut Uzel

I caught up with Aykut after the match. Since his life story encapsulates this article’s themes, I present our interview below.

Aykut Uzel: I grew up in a fairly insular milieu in Ankara. By my teenage years, I embodied all the cultural strengths and blind spots that that would normally entail. As a youth, I had never travelled abroad. It was through my discovery of tournament backgammon and my decision to become a professional player that I came to progressively integrate Western technology and cultural practices into my life, without abandoning my Turkish roots.

Backgammon has also been the means through which I have travelled the world and developed friendships in places like Copenhagen and London. Through hanging out in this globalized, but still quite Middle Eastern milieu, I came to question the assumptions and implicit prejudices that most Turks are raised with. In my late twenties, I made my first Kurdish and Armenian friends through our shared love of backgammon. As we bonded, I came to realize that they come from an extremely similar cultural and social-economic milieu to me and that there is no reason we should be enemies on a personal or even a political level. I also came to realize that coming from the same region and usually class background, we frequently shared more in common than I do with most Northern Europeans or Americans.

My backgammon style is built on a foundation of modern bot theory and deep study of computer analysis. However, as I am a backgammon professional cultivating Middle Eastern “clients” for a living, I incorporate elements of the traditional Middle Eastern preference for complex backgames and non-computer style plays that frequently lead to more exciting and artistic outcomes. This is not only fun for spectators, but it keeps the game “alive” globally and prevents it from being a solved and dead game like checkers or even chess.

In the final game of the final match of the 2021 Oasis Championship, I knew that I was making a “non-computer play” with my double 5s on move 5, but having previously sensed a weakness in my opponent’s understanding, I hoped to go into a massive 1970s-style backgame. My technically suboptimal gambit — according to the flawed methods of contemporary computer analysis as it comes to such positions — trapped him into various errors that allowed me to acquire enough timing to play a post-hit backgame type of position, known as “the snake.” This remains the only game type that modern neural net backgammon programs cannot sufficiently analyze and are bound to play worse than competent humans."

Aykut had not just mastered modern Performance Rating (PR)-driven backgammon in the bot era, he had infused it with his own Middle Eastern style — and in doing so, he created a work of art. The 99-move game, that his genius and cultural authenticity brought about, was one of the longest and most complicated backgammon games to ever be recorded and live-stream-commentated at a major tournament. (The average cubeful backgammon game is under 20 moves and even a long, complex backgame with extensive post-hit action is still usually under 45 moves.)

Aykut’s performance in the final — as well as his social encounters with Jews, Armenians, Arabs, and Kurds through the sport of backgammon — exemplifies where the Middle East might be heading, if certain favorable headwinds could be turned into a genuine direction of travel. Could it be that the world’s most conflictual region could actually be at the cutting edge of global reconciliation? Could the Middle East become a place where traditional and technological approaches blend together seamlessly and people finally learn to “just get along” and focus on our shared humanity and mutual interests?

Putting politics aside and sitting down together over a few games of backgammon certainly couldn’t hurt.

Jason Pack is a Non-Resident Fellow at MEI, the author of Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder, the President of Libya-Analysis LLC, and the 2018 World Champion of Doubles Backgammon. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own.

All photos are courtesy of the author.