Like the United States and Europe, Morocco, too, has seen inflation rates rise recently, recording a rate of 6.4% in July 2022, a telltale sign of so-called “imported inflation.” The government is viewing this developing situation with great apprehension, especially because Morocco had managed to avoid the rampant inflation that affected much of the Middle East and North Africa over the past decade. Thanks to its solid monetary policy, Morocco had been able to keep inflation to a minimum, but now the situation has changed and domestic monetary policy seems unable to address the external factors driving the recent rise.

After a government meeting at the end of May, the deputy minister for the budget said in a statement that inflation had reached 4.1% at the end of April 2022. However, earlier in March, after its quarterly meeting, Bank Al-Maghrib, Morocco’s central bank, stated that the annual inflation rate would reach 4.7% in 2022. Since then, the central bank has continued to forecast a higher inflation rate than the government anticipated, stating after its meeting in June that it expected annual inflation to reach 5%. But while the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates to curb inflation, Morocco’s central bank has not followed suit, instead keeping rates steady. This is because Morocco faces imported inflation and raising the interest rate would impede private investment and create more unemployment.

The Moroccan government faces a difficult situation, as high inflation is accompanied by a simultaneous slowdown in economic growth. In March, Bank Al-Maghrib forecast a growth rate of 0.7% for 2022, before adjusting its estimate in June to around 1%. This is down sharply from growth of 7.9% in 2021. The inflation rate and growth rate are inverse values, meaning that when inflation rises, economic growth declines, putting social stability at risk.

Morocco has benefited from relative stability over the past two decades thanks to a solid monetary policy that has kept domestic inflation rates under 2% most years. This monetary policy has also helped to maintain Morocco’s relative political and social stability during a period of social uprisings across much of the Middle East and North Africa. This success has given the current governor of Bank Al-Maghrib, Abdellatif Jouahri, a reputation for stability, compared to his counterparts across the region, many of whose countries were hit by massive waves of inflation. The governor’s thoughtful approach has kept him at the head of the central bank for a long time.

Jouahri brings substantial experience to the central bank, but his time as minister of finance between 1981 and 1986 is perhaps the most significant. At that time, Morocco was on the verge of bankruptcy and the International Monetary Fund and World Bank imposed a stringent structural adjustment program on the country, which reorganized the economy and public finances. The harsh lessons of the past taught the governor that Morocco’s stability is first and foremost linked to ensuring price stability and reducing inflation to the lowest possible levels.

In the past, high prices have led to tragic social upheavals in Morocco that have spiraled beyond the state’s control. On May 29, 1981, while Jouahri was minister of finance, bloody protests, in which victims were dubbed the “bread martyrs,” broke out, especially in Casablanca, after the government raised the prices of basic foodstuffs like flour, sugar, oil, milk, and butter. These protests were only one of a number of instances in which inflation put social stability to the test.

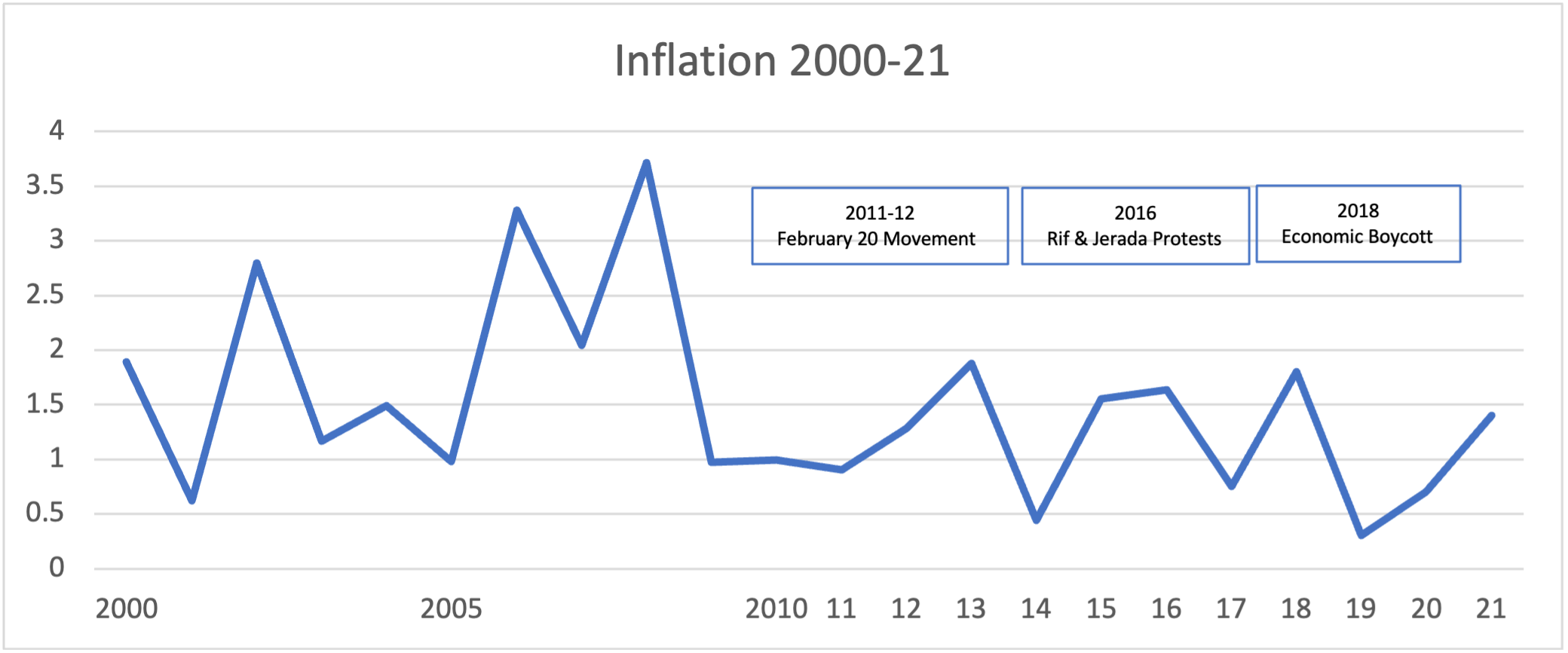

Over the past two decades, despite the relatively low rates of inflation compared to the 1980s and 1990s, some inflationary waves have shaken social stability. Morocco experienced three huge protest waves: The February 20 protests (the Moroccan Arab Spring), the Rif and Jerada protests, and the economic boycott campaign, all of which were linked to high prices and inflation, although each has its own context.

Since every increase in inflation has eventually led to the rise of protests, Morocco has learned the importance of effectively dealing with inflation. After 2010, as the inflation rate rose above 2%, social tensions also increased. Citizens’ earnings and purchasing power were very low since the overwhelming majority of the population could not save up and diversify their income. Most of their income, especially wages and profits, went toward basic necessities such as housing, transportation, food, and clothing. Even the middle class was chronically incapable of saving due to its weak purchasing power, its reliance on private educational services, and the high prices of urban residential real estate.

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, but before the outbreak of the Arab Spring uprisings, cities across the country held meetings to coordinate action against high prices and the deterioration of social services. In 2008 and 2009, the Moroccan street witnessed continuous protests against the rise in prices, after inflation reached 3.7% in 2008, its highest level since 2000.

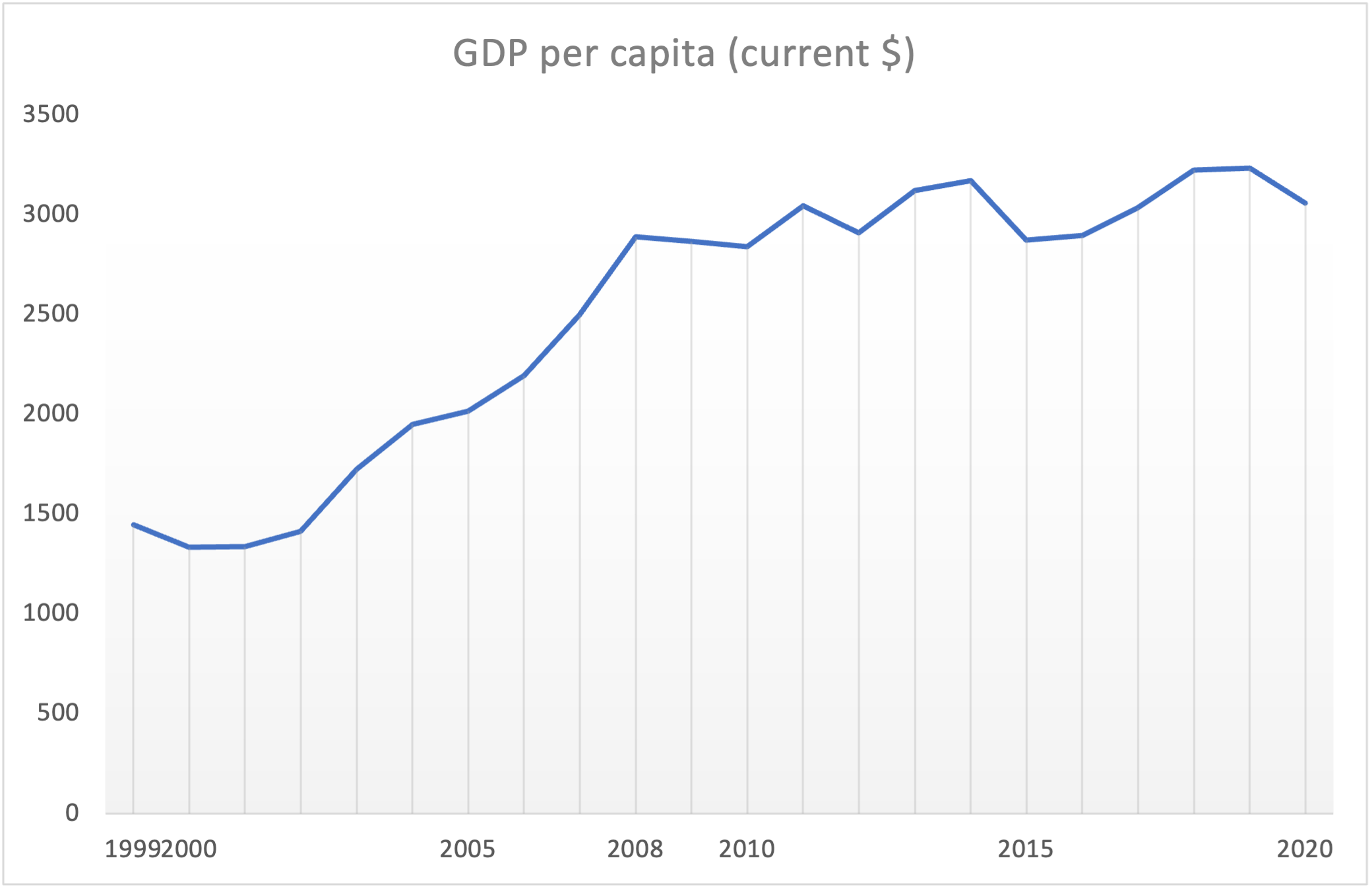

From 2000 to 2008, the Moroccan economy achieved significant growth, with annual per capita income levels among citizens more than doubling from $1,334 in 2000 to $2,890 in 2008. The increase in income has consequently lessened the impact of inflation on social stability. However, since 2011, the annual GDP per capita has remained at around $3,046, without any significant improvement over the following decade, reaching just $3,058 in 2021. This stagnation can largely be explained by Morocco’s weak economic growth, as well as other factors laid out in the New Development Model, an assessment report produced by a special committee on development in 2021. The report identified four key factors limiting growth:

- The lack of vertical coherence between the development vision and the announced public policies and the weak horizontal convergence between these policies.

- The sluggish pace of the economy’s structural transformation, hampered by high input costs and limited access for innovative and competitive new players.

- Limited public sector capacity to provide and ensure access to high-quality public services in areas critical for citizens’ daily lives and well-being.

- A sense of legal insecurity and unpredictability that limits initiatives, due to both a perceived disconnect between legal “grey areas” and social realities on the ground, and a lack of trust by citizens in the justice system, bureaucracy, and appeals process.

After 2008, given the inability of the Moroccan economy to raise annual per capita income levels, the high inflation rates became a greater concern, and during the Arab Spring protesters with the February 20 movement demonstrated against high prices. In 2022, marches took place celebrating the anniversary of the February 20 protests and condemning high prices, in an apparent repeat of history. But this time around, other factors were at play as well that contributed to the rise in inflation: the drought in Morocco, the effects of COVID-19, and the Russian war on Ukraine, which caused a sharp spike in energy prices, as well as the wave of inflation in advanced economies.

The COVID-19 crisis, combined with the stagnation of annual GDP per capita levels over the past decade, has led to the exhaustion of the Moroccan middle and working classes. It has particularly affected those in the informal sector, which represents 30% of the GDP and 70% of the country’s employment. Inflation under such circumstances puts a heavy burden on families and businesses, and it can weaken social stability, if distant or recent history is anything to go by.

The government has a narrow window in which to address the problem of inflation before things get worse. While Morocco may seem stable, history suggests this will not last and the mood on the streets can change quickly. There are already chants in the stadiums calling for the departure of the prime minister because of the current situation and the lack of government communication. The time for action is now.

Rachid Aourraz is an economist and co-founder of the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA), as well as a senior analyst. In addition, he is also a non-resident scholar with MEI’s North Africa and Sahel Program. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by STR/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.