Saudi Arabia’s strategy to push through its portfolio of clean and renewables assets was further strengthened in 2021 as the kingdom witnessed several project financings in the solar sector and launched the National Infrastructure Fund (NIF) to diversify its economy.

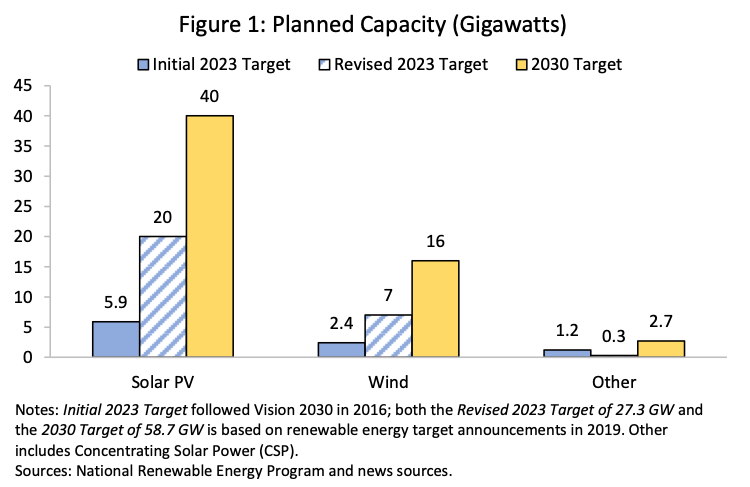

When Saudi Arabia first announced its Vision 2030 economic development plan, there was much discussion about its capacity to harness solar energy to ultimately curb emissions and displace its use of liquid fuel in electricity production — with the aim of exporting it instead, thereby monetizing its crude. In 2019, solar targets for both 2023 and 2030 were revised substantially upwards, with a targeted share of 20 Gigawatts (GW) and 40 GW, respectively for solar photovoltaics (PV) [Figure 1].

Having started modestly with 0.35 Megawatts (MW) at the turn of the century, installed solar capacity grew to 2.35 MW by 2010. By 2018, it rose substantially to 84 MW, of which 50 MW was concentrating solar power. Expansion of solar capacity continued to accelerate in 2019, reaching 394 MW on the back of the 300-MW Sakaka PV plant, which connected to the grid that November with a commercial operation date the following year in Q2 2020.

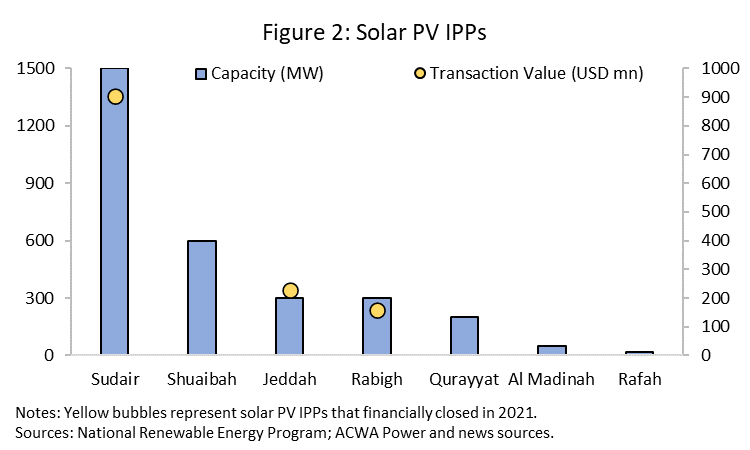

As the kingdom inaugurated Sakaka, its first-ever utility-scale renewable energy project under the National Renewable Energy Program in April 2021, seven independent power producer schemes for approximately 3 GW (2,970 MW) of PV projects were announced to have signed power purchase agreements (PPAs). Of these, Sudair, Jeddah, and Rabigh had reached financial close by mid-2021, together accounting for 2.1 GW; both Jeddah and Rabigh are scheduled to come online in 2022, and the first phase of Sudair is expected to begin producing electricity during the second half of 2022 [Figure 2]. This will bring total installed solar capacity to approximately 2.5 GW, or 12.5% of the revised 2023 target.

Sudair, the largest project at 1.5 GW, will require an investment of just over $905 million, with a levelized cost of electricity of 1.239 cents per Kilowatt-hour, and will receive $600 million in project financing (equal to 66% debt) from a consortium of local and international financial institutions. Rabigh, at 300 MW, became one of the first renewables projects to draw on financing from an export credit agency; Japan’s Bank of International Cooperation provided a soft mini-perm structure amounting to approximately $78 million, which has been combined with an Islamic facility tranche. All projects tendered by the Ministry of Energy are backed by 25-year PPAs with the Saudi Power Procurement Company as offtaker.

Saudi Arabia plans to generate 50% of its electricity from clean sources by 2030. This is to be implemented by complementary tracks pursued by both the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources, tendered by the Renewable Energy Project Development Office, which will oversee the procurement of 30% of this target via a competitive process; the kingdom’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) is set to deliver the remaining 70% through direct negotiations with investors in an effort to develop Giga-scale projects. However, according to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2021, only 0.3% of its electricity supply came from renewable energy in 2020 — its latest available figures — thereby necessitating more investment if Saudi Arabia wants to meet its ambitious goals for renewables.

Nonetheless, October witnessed strong momentum for climate action from the kingdom as it announced a net-zero target for 2060 ahead of the COP26 U.N. Climate Change Conference and updated its Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. With the UAE, it pledged $340 billion in net-zero investments to be allocated to renewable energy, storage, and hydrogen, including carbon capture, utilization, and storage projects — the latter of which will help drive Saudi Arabia’s "Carbon Circular Economy" approach to achieve its goals.

In parallel, it also announced the establishment of an NIF, enlisting U.S. asset manager BlackRock to help advise on it. This Fund — backed by Saudi Arabia’s National Development Fund, which was set up in 2017 — has an investment target of $53 billion spanning various sectors, including power and water, and is likely to further propel investment in renewables. It is set to participate through debt and equity, and offer credit guarantees to mobilize domestic and foreign capital.

Targeted funds are not a new development, especially for economies that are both resource-rich and -dependent, and ring-fenced vehicles have previously been set up by several countries to play active roles in facilitating financing in strategic sectors. Examples include the Nigeria Infrastructure Fund, established by the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) in 2013, and allocated $600 million. Its investment mandate focuses on actively developing greenfield projects in five core sectors, such as health care, motorways, and power, to stimulate growth and diversification, as well as attract foreign investment. Noteworthy is a key performance indicator of additionality: the financing of projects that otherwise would not have happened without its involvement. More recently, NSIA partnered with the Central Bank of Nigeria and Africa Finance Corporation to establish the Infrastructure Corporation of Nigeria Ltd (InfraCorp), an infrastructure special purpose vehicle that will complement the existing Fund. Nigeria has assigned four asset managers to manage the $37 billion InfraCorp, similar to Saudi Arabia’s approach. Another example is the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund, which started operations in 2015 with a $325 million equity injection. It currently has $275 million committed across a diverse infrastructure portfolio, with 75% composed of debt instruments, and 20% and 5% from equity and mezzanine financing, respectively.

Saudi Arabia’s NIF will no doubt contribute to de-risking infrastructure projects and promote innovative financing solutions, thereby deepening the country’s capital markets. What remains to be seen, however, is the mechanics and impact of such an endeavor on an economy that has identified infrastructure as one of its key pillars in Vision 2030.

Lama Kiyasseh is an energy economist and infrastructure development professional with extensive international experience in emerging markets. She is currently at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s development finance institution, with a portfolio that covers investments in climate finance. She is also a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Economics and Energy Program. The views expressed in this piece are her own.

Photo by FAYEZ NURELDINE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.