Summary

In 2016 the Turkish parliament voted to revoke parliamentary immunity and initiated the ruling Justice and Development Party's (AKP) political purge of MPs with the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Despite the introduction of a new assembly in 2018, Turkey’s October invasion of northeast Syria provided ample incentives for the launch of new investigations into HDP members protesting the operation. The targeting of the HDP has set new legal and political precedents that could undermine the political capacity of the opposition coalition as a whole and create ideological divisions over the so-called “Kurdish Question.” This report records documented arrests of HDP MPs from June 2016 to January 2018 in order to identify prominent trends and waves of arrests that correspond to political and legal events.

Contents

- Introduction

- The HDP's Crisis

- Methodology

- The Lineage of Political Oppression

- HDP Leadership

- Immunity

- The Charges

- Pushed Out of Parliament

- Legal Practices and Scare Tactics

- Timeline

- New Criminal Proceedings and Immunity Revocation

- Connecting the YPG and the PKK

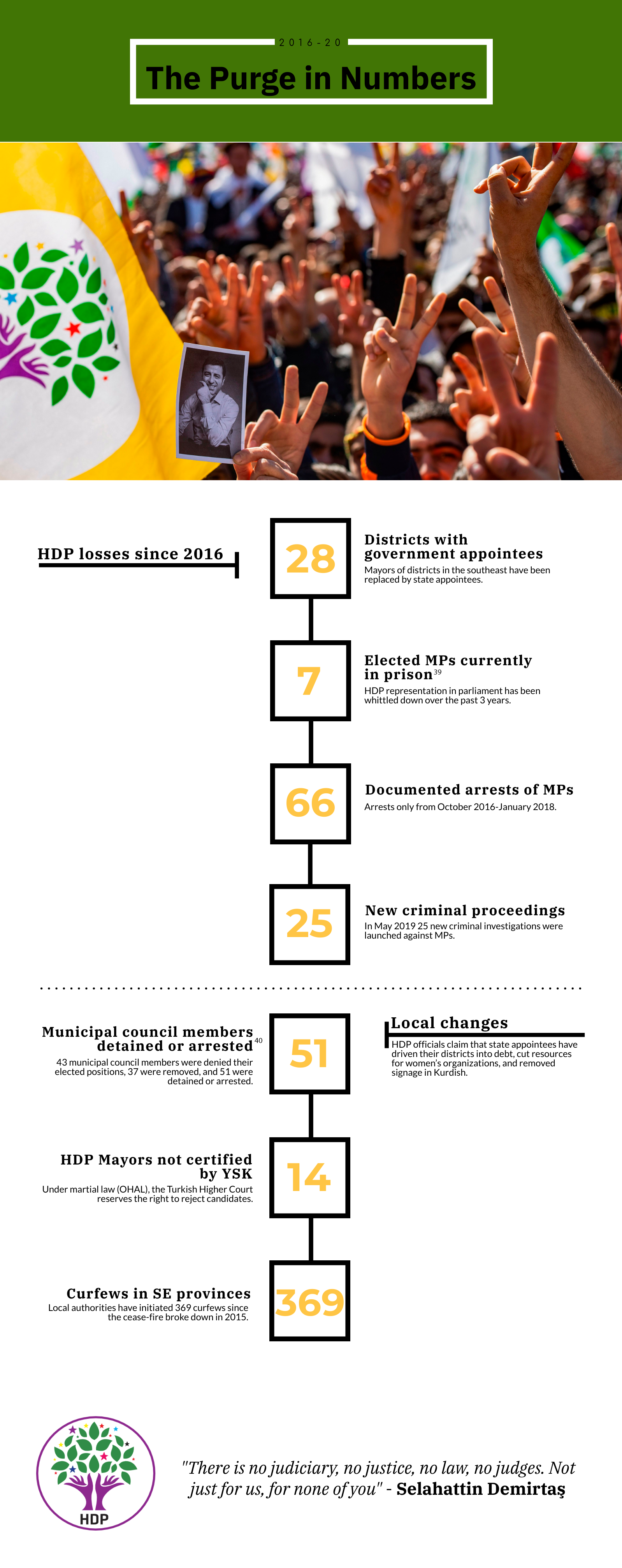

- The Purge in Numbers

- Ya Me Ye "It Is Ours"

- The Coalition's Future

- Endnotes

Introduction

On Nov. 20, 2019 Turkey’s Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) announced that it would remain in parliament and refrain from exercising the so-called “nuclear option” (the sine-i millet option). HDP officials had been considering resigning from their posts en masse in the hope of spurring an interim election. HDP spokesman Günay Kubilay had previously said that the proposed mass resignation from parliament was “a democratic and legitimate proposal” and several party members had voiced their support for the move.1 Instead, HDP officials took the less drastic approach and simply called for an early election in a bid for support from other coalition parties: the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Felicity Party (SP), and the Good Party (Iyi Parti). Public polls showed many supporters calling for a stronger response from HDP officials to the mass purge of their politicians, but also that they did not prefer the sine-i millet option.

In response to the HDP statement that they would remain in parliament, the CHP said that they would vote in favor of an early election if it were proposed, despite party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s statement in August that the Turkish people are “tired of elections.”2 The same day, the SP announced that it would also support a snap election. Snap elections have played a key role in the electoral success of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), yet Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, denounced this latest call for early elections, implicitly acknowledging his declining support. Despite recent hemorrhaging of backing from the AKP, the move to call for early elections is largely symbolic as snap elections require 60 percent of parliament to vote in favor, and Erdoğan’s coalition currently holds 53 percent of the seats.3 More potent is the message that the HDP has not altogether abandoned hope in the political process and the opposition coalition, despite significant barriers to its political activity.

The HDP’s Crisis

Since the attempted coup in 2016 Erdoğan has wielded unchecked power, carrying out massive purges of alleged Gülenists, Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) sympathizers, and those who simply dared to defy or insult him. The passing of a bill to revoke the immunity of members of parliament (MPs) famously ended in blows as some HDP members recognized the amendment as the beginning of the end for their party.

The Western media has paid considerable attention to the Kurdish armed movement in Syria known as the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and its relationship with Ankara. Yet there has been little coverage of how Turkey’s October invasion of northeast Syria, known as Operation Peace Spring, has affected Kurdish movements in Turkey and the opposition movement as a whole. Erdoğan’s foreign policy decisions often reflect his waning domestic support and serve to distract or divide the opposition. The October incursion was no different, and it reinvigorated nationalist sentiment among supporters of the AKP and the opposition alike. Moreover, this latest military operation was in effect condoned by parliament as it voted to approve six more months of military presence in Iraq and Syria.4

The only major party to disapprove, the HDP, was silenced by a new wave of arrests and investigations against party members. Protests against Operation Peace Spring were violently suppressed, with some MPs being physically obstructed and prevented from making statements, escalating to the point that one was even pepper sprayed in the face in front of his own office. New hearings on revoking MPs’ immunity targeting primarily HDP officials have threatened the very existence of the party before the next round of elections, scheduled for 2023.5 Although the leading opposition party, the CHP, has performed several acts of solidarity with the HDP over the past year, its nationalist creed at a time of rising anti-Kurdish sentiment has raised questions about the durability of its tenuous alliance with the HDP.

"Although the leading opposition party, the CHP, has performed several acts of solidarity with the HDP over the past year, its nationalist creed at a time of rising anti-Kurdish sentiment has raised questions about the durability of its tenuous alliance with the HDP."

Methodology

This report records documented arrests of HDP MPs. It uses “arrests” to refer to both temporary detainments and arrests that led to prison sentences. In many cases MPs are arrested twice over the course of one or two days. In most instances, they are released the next day. It should be noted that the arrests documented here only represent those which were reported on and likely do not reflect the real total number of arrests carried out against HDP MPs. Likewise, these numbers do not include other HDP supporters or officials who have been arrested or ousted. This report does not attempt to determine the veracity of the alleged crimes but rather seeks to highlight the prominent trends and waves of arrests that correspond to political and legal events.

The Lineage of Political Oppression

The HDP has been represented as the de facto “Kurdish party” but its initial campaign attracted the support of young leftists, minority voters, and Istanbulites alike. For many, its liberal platform offered one of the only alternatives to the nationalist parties in parliament.

The HDP was formed in 2012 as the newest iteration of a series of leftist political movements that were quickly associated with Kurdish nationalism (and subsequently banned) despite their broader political agendas. The HDP was formed from a coalition of leftist parties known as the Peoples’ Democratic Congress (HDK) in order to surpass the 10 percent electoral threshold for parliamentary representation and promote independent candidates. The HDP was founded as a democratic socialist party with a particular emphasis on protecting the rights of minorities. Its symbol, a multicolored tree reminiscent of the trees that sparked the Gezi Park protests, encompasses its promotion of diversity and the values of the Gezi Park protest movement, such as environmentalism, gender equality, diversity, democracy, and socialism.6 In 2014 the HDP ran detained politician Selahattin Demirtaş as its candidate in the presidential election. He finished in third place and became a popular figure, known for his powerful speeches and dedication to a peaceful political process. In 2015, the HDP surpassed the 10 percent threshold and entered parliament with 13 percent of the seats in what was seen as a resounding blow to the AKP.7

Since its founding, the HDP has faced allegations of affiliation with the PKK, a Kurdish militant group that has carried out terrorist attacks against both Kurdish and Turkish civilians, as well as security forces. The AKP does not distinguish between the YPG and the PKK, alleging that they are both terrorist organizations that pose an existential threat to the Turkish state. The HDP offered an alternative to the PKK that was growing in both support and relevance, and from 2014-15 HDP officials served as key negotiators between the PKK and the AKP in an effort to establish a new cease-fire.8 Demirtaş, who was sentenced to more than four years in prison in 2018, has vehemently denied the HDP’s and his own association with the PKK. In 2017 he reiterated, in response to the charges against him, “I am not a manager, member, spokesperson, or a sympathizer of the PKK. I am the co-chair of the HDP; and I criticize all means of violence and war, and I stand against such policies.”9

The collapse of the cease-fire with the PKK in 2015 followed by the launch of Turkish military offensives into Syria in 2016 (Operation Euphrates Shield) and 2018 (Operation Olive Branch) heightened tensions between Turkish officials and Kurds and served a fatal blow to the HDP. As the party’s politicians began to speak out against Turkish operations in both Syria and southeast Turkey, AKP representatives introduced legislation to strip MPs of their immunity.

In the wake of the 2016 coup attempt Erdoğan consolidated his grip on power and conducted purges against “terrorists” with little opposition. As clashes between the PKK and the Turkish military escalated in 2016, the first HDP officials were investigated and the administration began to systematically purge members of the party from political posts.

"In November 2016 both party co-presidents of the HDP were arrested and eventually removed from office. ... Both Yüksekdağ and Demirtaş remain in jail."

HDP Leadership

In November 2016 both party co-presidents of the HDP were arrested and eventually removed from office. In January 2017 prosecutors announced that they were seeking a 142-year sentence for Demirtaş, and in 2018 he was sentenced to four years in prison for a speech he made during a Newroz celebration.10 The New York Times reported that Demirtaş was facing “100 charges ranging from terrorism to insulting ... President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan”.11 Despite his incarceration, Demirtaş ran for president from prison in 2018 and finished in third place once again. His is still viewed as the authoritative voice on the HDP and Kurdish rights, with a popularity that rivals that of PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan. Also imprisoned is former HDP co-president Figen Yüksekdağ, who was sentenced to six years in jail on similar charges. She was arrested for refusing to testify, “making propaganda for a terrorist organization,” and “overtly insulting the government of the Turkish Republic.”12 Yüksekdağ has been charged in 27 different criminal cases, with five so far resulting in prison sentences.13

Both Yüksekdağ and Demirtaş remain in jail. The ousted co-presidents’ positions were filled by Sezai Temelli and Pervin Buldan. Both have now had investigations launched against them after they criticized the detainment of other HDP officials as well as Operation Peace Spring.14

Immunity

The practice of revoking parliamentary immunity for Kurdish politicians is not new but the process involved has changed. Previously, primarily pro-Kurdish rights and overtly religious parties would be banned, leading to their members’ parliamentary immunity being revoked and leaving them open to charges or initiating their ban from politics. Ironically, Erdoğan’s own party was banned in the late 1990s and he was ousted from his position as mayor of Istanbul in 1998 based on a poem he recited a year earlier.15 In 2009 the Democratic Society Party (DTP) became the most recent of the six pro-Kurdish rights political parties to be banned.16 The ban resulted in an increase in violence in the southeast and then-Prime Minister Erdoğan, in the midst of attempting to conduct a peace process with the PKK, opposed the ruling.17

In 2016 the process of revoking immunity changed. A constitutional amendment that year was supported by Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), AKP, and CHP MPs alike. Erdoğan was upfront about who the amendment would target, as he stated that he did not want to see “guilty lawmakers in this parliament, especially the supporters of the separatist terrorist organization.”18 HDP representatives saw the CHP’s support for the amendment as a betrayal and a misstep for the entire opposition movement. CHP leader Kılıçdaroğlu stated that his party would prefer the amendment apply to all members of parliament, not just those under investigation, but would support it nonetheless.19 The amendment itself is a temporary measure that stripped 138 MPs currently facing investigations for criminal charges of their immunity. At the time of the proposed amendment “51 opposition CHP members of parliament, 50 HDP MPs, 27 AKP MPs, nine … MHP MPs and one independent” MP were facing investigations.20

Supporters of the bill pointed to the fact that the amendment could be used against members of all parties and was thus a bipartisan attempt to clean up parliament. However, the arrests documented in this report show that the investigations carried out against MPs have been almost entirely concentrated on HDP representatives based on charges of “propaganda” rhetoric. Demirtaş stated that there “are 15 separate incidents in 2015 where Devlet Bahçeli [chair of the MHP] had called President Erdoğan a ‘thief’ and made similar comments. But no legal action has been taken against him because of his statements. Because laws in this country are applied to me differently than they are applied to Devlet Bahçeli.”21 The amendment has not been used to target corruption or illicit behavior beyond scrutinizing political rhetoric and alleged ties to the PKK.

Since the passing of the constitutional amendment, politicians can lose their parliamentary immunity while belonging to a legal party. The process of revoking their immunity begins with the launch of a formal investigation and the summary proceedings are then sent to parliament, where the immunity of each MP under investigation is voted on one by one.

HDP co-chairs Demirtaş and Yüksekdağ wrote in a letter to members of the European Parliament that they “view this motion as a political coup attempt to completely destroy the separation of powers by subordinating the legislative to the executive and leaving the former to the mercy of a thoroughly politicized and biased judiciary.” While HDP members have appealed to the Turkish Constitutional Court (AYM) to review both the lifting of parliamentary immunity for members and the pre-trial detention of politicians, the court rejected the request, stating that although the AYM is authorized to review the lifting of immunity for MPs, the amendment was a “special process” with “special political consequences.”22 The European Commission for Democracy Through Law stated that “in the current situation in Turkey, parliamentary inviolability is an essential guarantee for the functioning of parliament.”

"Most of the charges leveled against HDP officials are based on accusations of spreading terrorist propaganda through speeches or social media, being a member of a terrorist organization, attending the funerals of PKK members, insulting the president, refusing to testify, or participating in protests."

The Charges

Most of the charges leveled against HDP officials are based on accusations of spreading terrorist propaganda through speeches or social media, being a member of a terrorist organization, attending the funerals of PKK members, insulting the president, refusing to testify, or participating in protests. This report references 66 documented arrests and detainments of HDP MPs from March 2016 through January 2018, revealing a pattern of harassment on seemingly unsustainable charges.

Pushed Out of Parliament

As a result of investigations against them, 14 HDP members of the 26th parliament were removed from office. Osman Baydemir, Aysel Aydoğan, Tuğba Hezer, Faysal Sarıyıldız, Selma Irmak, Leyla Zana, Besime Konca, Ahmet Yıldırım, Gülser Yıldırım, İbrahim Ayhan, Ferhat Encü and Burcu Çelik Özkan, as well as Demirtaş and Yüksekdağ, were stripped of their parliamentary positions and/or are currently in prison. Some fled the country in anticipation of the long sentences awaiting them, while others were banned from leaving Turkey and had their passports confiscated.

"The first wave [of arrests] on Nov. 4, 2016 was by far the largest and had the greatest impact. The arrests took place shortly after the start of Operation Euphrates Shield."

Legal Practices and Scare Tactics

There are a few perceptible patterns in the investigations and arrests of HDP members. The frequency of the arrests without trial or sentences indicate insufficient evidence or political will to bring the MP to trial. Likewise, MPs are often forced to testify against themselves or other MPs. They are usually investigated in batches based on a political event they were present at or rhetoric they allegedly supported. As a result, politicians are often detained after refusing to testify against their fellow MPs or themselves. Likewise, as the immunity revocations are based on ongoing investigations and not convictions, MPs are often pushed out of office based on unsubstantiated claims.

Timeline

The arrests documented in this report show six major waves of increased activity. It should also be noted that arrests of HDP MPs occurred both before and after the timeline above. The first wave on Nov. 4, 2016 was by far the largest and had the greatest impact. The arrests took place shortly after the start of Operation Euphrates Shield on Aug. 24, 2016. Many of the charges were spurred by HDP representatives’ participation in protests against the operation. The November arrests included Demirtaş and Yüksekdağ. The administration also allegedly blocked internet and social network services across the country.23 Two of the MPs were traveling abroad (Faysal Sarıyıldız and Tuğba Hezer Öztürk) when the arrests took place while 12 others — Nursel Aydoğan, İdris Baluken, Ziya Pir, Selma Irmak, Abdullah Zeydan, Gürsel Yıldırım, Nihat Aydoğan, İmam Taşçıer, Lezgin Botan, and Leyla Birlik, along with Demirtaş and Yüksekdağ — were detained.

The second wave occurred in December 2016. On Dec. 10 two car bombs killed 38 people outside a soccer stadium in Istanbul.24 The attack was claimed by the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks, a violent Kurdish nationalist group that many consider an offshoot of the PKK. Two days later Turkey detained 235 people over alleged links to the PKK.25 HDP MPs Hüda Kaya, Besime Konca, Çağlar Demirel, Nimetullah Erdoğmuş, Alican Önlü, and Mehmet Emin Adıyamanwere arrested within the next week.

The third wave of arrests took place shortly after, in January 2017. Ahmet Yıldırım, Ayhan Bilgen (twice), Ayşe Acar Başaran, Adem Geveri, Meral Danış Beştaş (twice), Nadir Yıldırım, Altan Tan, Lezgin Botan (twice), İmam Taşçıer, Ziya Pir, Emin Adıyaman, and Hüda Kaya were arrested in the latter half of January. (MP Leyla Birlik was also charged but fled to Greece.) Most of the politicians were briefly detained in order to take them to their trials to provide testimony. Most HDP MPs refuse to attend their trials or testify as a form of protest. This tactic has led to further detainments and forced testimonies.

Leyla Zana, Dilek Öcalan, Mehmet Ali Aslan, Behçet Yıldırım, Ferhat Encü, İbrahim Ayhan, and İdris Baluken were arrested or detained in February 2017 as Erdoğan prepared for a referendum on a new constitution that would allow the president sweeping powers over parliament. On Feb. 14 the Turkish government arrested 800 people on charges of links to the PKK.26 Some 300 HDP members and executives were also arrested that day.27 All of the documented MP arrests in February were based on charges of connections to the PKK or rhetoric in support of the terrorist organization.

Dirayet Taşdemir, Berdan Öztürk, and Mehmet Emin Adıyaman were arrested the next month just weeks before the constitutional referendum. The arrests in March 2017 primarily correspond to HDP candidates’ participation in the “no” campaign against the constitutional referendum, which took place in April. The HDP executive committee released a statement saying that “the basic goal of these operations ... is to hold the referendum without the HDP.”28

Most of the arrests in July 2017 were continuations of ongoing investigations. While Saadet Becerikli was arrested for interrogation for a speech she made, Adem Geveri for attending a protest and Dirayet Taşdemir as part of an ongoing investigation, Ayşe Acar Başaran and İbrahim Ayhan were both arrested because they did not testify or attend their hearings.

"Although HDP officials advocate for a nonviolent political process, Turkish national media portrays the HDP as part of the PKK."

New Criminal Proceedings and Immunity Revocation

The snap elections in 2018 ushered in a new cohort of HDP MPs with newfound immunity. The 2016 amendment stipulated that only MPs with formal investigations that began after May 2016 would be considered for criminal proceedings before parliament. Notably this new round of targets included members of both the Iyi Parti and the CHP, none from the MHP, and the vast majority from the HDP. The new investigations targeted both CHP leader Kılıçdaroğlu (who had previously voiced his party’s support for the amendment) and the new co-president of the HDP, Pervin Buldan.

List of MPs being investigated: HDP İzmir MP Serpil Kemalbay Pekgözegü, HDP Ağrı MP Berdan Öztürk, HDP Diyarbakır MP Remziye Tosun, HDP Diyarbakır MP Musa Farisoğulları, HDP Diyarbakır MP Salihe Aydeniz, HDP Gaziantep MP Mahmut Toğrul, HDP Mardin MP Ebrü Güni, HDP Mersin MP Rıdvan Turan, HDP Şanlıurfa MP Ayşe Sürücü, HDP Diyarbakır MP Semra Güzel, HDP Şırnak MP Hüseyin Kaçmaz, HDP Şırnak MP Nuran İmir, HDP Mardin MP Mithat Sancar, HDP Şırnak MP Hasan Özgüneş, Turkish Workers’ Party (TİP) Hatay MP Barış Atay Mengüllüoğlu, TİP İstanbul MP Erkan Baş, CHP İzmir MP Selin Sayek Böke, CHP İstanbul MP Saliha Sera Kadıgil Sütlü, CHP Tekirdağ MP İlhami Özcan Aygun, Iyi Parti Konya MP Fahrettin Yokuş.29

Despite the apparent (albeit perhaps temporary) immunity of new MPs, their advisors and colleagues have still been subjected to arrests and police activity. In Kocaeli the HDP office was raided and a Turkish flag was pinned to the wall. Three computers and one hard drive were confiscated.30 Newly elected 23-year-old HDP MP Dersim Dağ was briefly detained and allegedly beaten by police officers during a protest against Operation Peace Spring.31 Most recently an unidentified gunman fired seven shots in the air in front of the HDP headquarters in Istanbul.32

Connection to the PKK and YPG

“The HDP equals the PKK, which equals the People’s Protection Units (YPG)/the Democratic Union Party (PYD).”33 – President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Only hours after the Nov. 4, 2016 arrests, a bomb went off near one of the facilities holding the politicians in Diyarbakır. Nine people were killed and 100 injured.34 The bombing was later claimed by ISIS, but the Turkish government implicated the PKK. The bombing characterized the violent alternative to the political process and indicated that the purge of politicians would herald new PKK terrorist attacks in the already bloody post-cease-fire environment. This process is neither new nor unrecognized. During the cease-fire that the AKP initiated in 2013, which lasted until 2015, Erdoğan and his peers acknowledged the need for strengthened political representation and cultural expression to curb violent resistance and reduce support for the PKK.

HDP officials claim that Erdoğan’s reversal on the so-called Kurdish question was spurred by the 2015 election success of the HDP. Suddenly the HDP played a more important role in supporting the opposition movement. Undoubtedly, the launch of Turkish operations in northeastern Syria against the YPG, and the Syrian Democratic Forces more broadly, intensified nationalist rhetoric about the PKK and motivated AKP officials to curb protests that referred to the YPG as anything but terrorists.

Although HDP officials advocate for a nonviolent political process, Turkish national media portrays the HDP as part of the PKK, acting in tandem with and supporting it with funds and political favors. The HDP for its part denies all links to the PKK. In the charges that the HDP supports the PKK, attendance at the funerals of PKK or YPG members is the most commonly cited evidence. It is undeniable that many HDP representatives have attended the funerals of some individuals who at one time belonged to the PKK or the YPG. In fact, many of the funerals attended by HDP members are those of family members. Demirtaş himself has a brother whom he has acknowledged was active in the PKK.35 HDP MP Garo Paylan stated that when HDP “deputies attend funerals, this does not mean they support the actions of the PKK militants. It is a show of respect for the families who have lost their son or daughter, and simply shows the emotional damage Kurds have endured as a result of the vicious conflict.”36

Many of the HDP’s Kurdish constituents also show support for jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. This support contributes to the AKP narrative that the HDP itself supports the PKK and is a sister organization of the violent insurgent group. However, rhetoric from party leaders, as well as several HDP policy decisions, contradict this claim. One recent example came in June 2019 when the HDP immediately told its voters to defy supposed instructions from Öcalan encouraging Kurdish voters to abstain from backing CHP candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu in a rerun of the Istanbul mayoral election.

Former party leader Demirtaş has been explicit about the role Öcalan should play in Kurdish politics in his interviews. He says “no peace process can be ultimately successful without Öcalan’s participation — which is why, several years ago, Erdoğan himself explored options for peace with the PKK leader.”37 Nevertheless, Demirtaş has been careful to distance the HDP from Öcalan, without alienating those who see Öcalan as an important Kurdish figure, and stress that his party members “continue to work without losing our belief in democratic and peaceful resistance.”38

While the chaotic political environment and growing popular frustration may have provided ideal conditions for the rekindling of PKK violence in the past year, it is also worth noting that the PKK has been significantly weakened in its ability to carry out attacks. Turkish drone operations on the PKK’s leadership in the Qandil Mountains in Iraq and southeast Turkey have reduced the capacity of its militants. In the past the PKK has proved extremely effective in recruiting and re-establishing its structure after extensive operations against it. Nevertheless, with the threat of more violence erupting, the HDP’s decision to remain politically active is crucial in providing a non-violent outlet for Kurdish activists. HDP officials have been charged with inciting hatred and propagandizing for the PKK, but the dissolution of Kurdish political representation is perhaps the best propaganda for the PKK that the government could produce.

Ya Me Ye "It Is Ours"

Local Kurdish representatives have taken the biggest hit in the purge. The HDP had been shedding mayors and local representatives even before the 2016 decision to lift immunity for members of parliament.41 Mayors and local administrators never enjoyed immunity, but since the implementation of martial law in 2016 they have been subject to an increasing level of investigations. The government has employed similar tactics of mass arrests and attempts to silence demonstrators and advocates in the southeast, including local administrators.

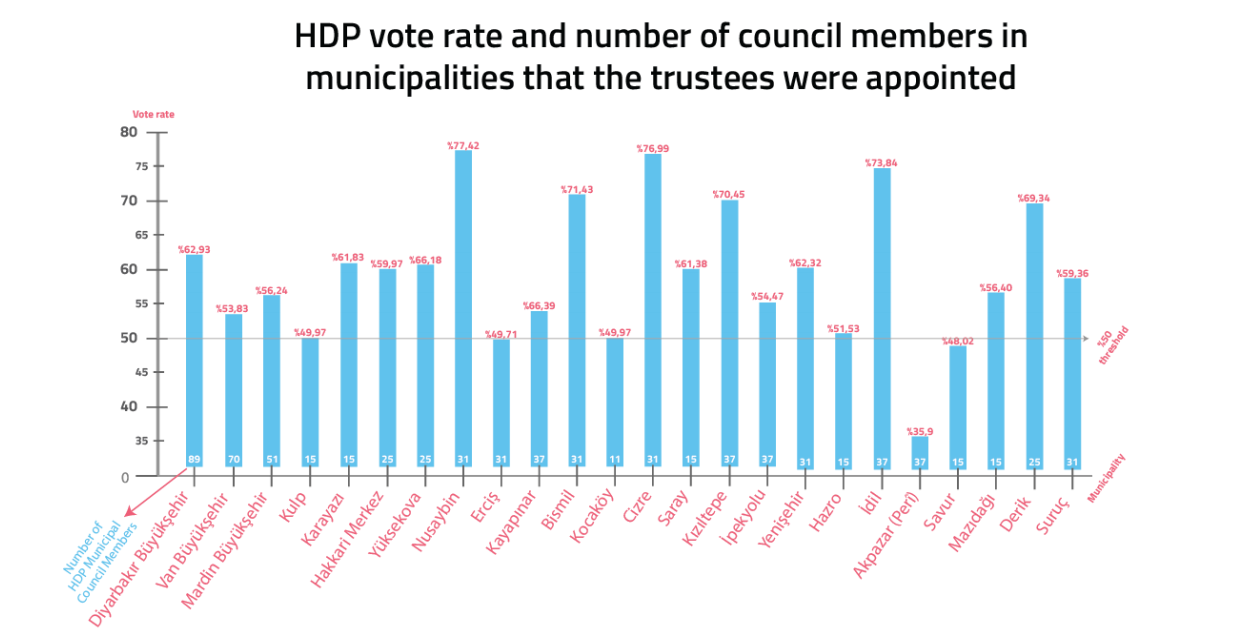

Mayors of districts that were affected by the 2015 fighting with the PKK, in which sections of cities were cordoned off by insurgents and entire neighborhoods were destroyed, comprised most of the initial dismissals. However, later on mayors who had not even taken office yet were deemed unsuitable and replaced. Under the Governorship of Region in a State of Emergency (OHAL), a type of martial law in Turkey enacted once again after the 2016 coup attempt, the Turkish Higher Court (YSK) rejected 14 mayoral candidates that had been elected by popular vote. After the 2019 municipal elections, six candidates were outright rejected by the YSK and eight have yet to be certified.42 As a result, “the mandate was not given to 44 municipal council members and three provincial council members … 47 council members in total, though they were elected.”43

According to a recent report by the Diyarbakır branch of the Human Rights Association, “37 [municipal council members] were removed from their positions, and 51 more were either detained or arrested.”44 Political parties have members of municipal council members in relation to the votes they receive, while metropolitan council members are directly elected. Municipal councils enact policy on the local level and “have authority in the evaluation of policies as well as in the phases of preparation and implementation.”45

Simultaneously, in 2016 and before, mayors were replaced due to ongoing investigations against them. However, in the 2019 local election many new members from the Democratic Regions Party (DBP), a local sister party of the HDP, and HDP mayors replaced their incarcerated or investigated peers. Since the 2019 election in March, kayyums — government officials appointed by the central government — have been appointed in these 28 municipalities: Diyarbakır (Büyükşehir), Van (Büyükşehir), Mardin (Büyükşehir), Hakkâri (Büyükşehir), Yüksekova (Hakkâri), Kulp (Diyarbakır), Kayapınar (Diyarbakır), Bismil (Diyarbakır), Kocaköy (Diyarbakır), Karayazı (Erzurum), Nusaybin (Mardin), Erciş (Van), İpekyolu (Van), Cizre (Şırnak), Saray (Van), Kızıltepe (Mardin), Yenişehir (Diyarbakır), Hazro (Diyarbakır), İdil (Şırnak), Akpazar (Dersim), Mazıdağı (Mardin), Savur (Mardin), Derik (Mardin), Suruç (Mardin), Muradiye (Van), Özalp (Van), Başkale (Van), and İkiköprü (Batman). An article published by Hürriyet in December states that 31 municipalities now have state appointees. In addition to the replacement of officials, at least 16 co-mayors have been arrested and 23 co-mayors have been jailed pending trial.46

Beyond the controversy over the replacement of mayors, residents have also witnessed drastic changes in policy and budget spending upon receiving new mayors and local officials. In 2015, the latest cease-fire between the PKK and the Turkish government collapsed and chaotic fighting erupted for the first time in more urban settings in the southeast. As a result whole neighborhoods in Diyarbakır, Cizre, Van, and Nusaybin were destroyed. Some residents opposed the reconstruction of these neighborhoods by the central government that many blame for destroying them in the first place. The historic district of Sur, Diyarbakır, which had just won designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site before the conflict reignited, proved a particularly complex process of reconstruction.47 In May 2016 the central government seized 82 percent of the area and AKP officials claimed that they would dedicate $11 million to reconstruction efforts.48 In August of the same year, the mayor of Diyarbakır was ousted and in December she was arrested.49 Urban designers and architects who had been preparing for Sur’s UNESCO World Heritage status are now expressing concernat the changes appointees have planned for the historic district. Many of their concerns are focused on the government’s ability to provide affordable housing and the demolition of informal housing. Most residents of Sur were displaced and paid meager sums for their property.50

In nearby Mardin, the current mayor, Ahmet Türk, claimed that when he was dismissed from his post in 2016 the city had $15 million in cash on hand, but that when he reclaimed his post in the 2019 elections the city was $63 million in debt.51 He has since been removed from his seat for a second time.

Some residents claim that the new mayors have also attempted to “Turkify” their municipalities and reversed many of the measures adopted by previous officials to represent their community. In Diyarbakır some street signs which displayed the names of cities, neighborhoods, and mosques in both Kurdish and Turkish have been replaced by signs exclusively in Turkish.52 Kayyums have also closed all municipality departments for women, which provided support for women’s organizations and two women’s shelters. Kurdish activist Nurcan Baysal claims that in the first wave of purges in 2016, 43 women’s organizations across the southeastern provinces were closed by kayyums.53 In addition to changes in budget allocations and Kurdish signage, kayyums have adopted new security measures that are more intrusive into the daily lives of residents, including the imposition of curfew 369 times since 2015, disruptive internal security checkpoints, and even a rising death toll caused by armored vehicles in the area.54

On Nov. 6, 2019 the Turkish government also appointed mayors in the provinces of Gire Spi (Tal Abyad) and Serê Kaniyê (Ras al-Ayn) in Syria occupied during Operation Peace Spring. The mayors are connected to the province of Şanlıurfa (similar to the process carried out after Operation Euphrates Shield), and Turkish officials say that they have already started to provide basic services and to construct a local law enforcement apparatus.55

The Coalition’s Future

Five days before CHP mayoral candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu’s second victory in the Istanbul municipal elections in June 2019, Demirtaş explicitly called for HDP supporters to vote for him, and this may have been one of the deciding factors in İmamoğlu’s win. In recognition of this, İmamoğlu thanked HDP supporters in his acceptance speech. Following up on this, on Sept. 2, 2019, the new Istanbul mayor met with the ousted HDP mayor of Diyarbakır and expressed his support, saying, “We are on the same ship” with the HDP.56 His visit to Diyarbakır was a historic move toward solidarity between the coalition parties. In a similar show of solidarity, both former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and former President Abdullah Gül said on Twitter that the dismissals were not in keeping with democracy.57

The AKP’s targeting of the HDP has significantly changed the outlook for the opposition in the upcoming 2023 elections. Beyond the loss of HDP representatives in parliament and at the local level, the degradation of the HDP and the division of the Kurdish vote have created several ideological divides between the opposition parties. Operation Peace Spring, like Operation Euphrates Shield and Operation Olive Branch, was announced at a pivotal moment for the coalition and during a period of declining support for Erdoğan. The previous operations all preceded elections and provided a boost in nationalist support. According to Reuters, a Metropoll survey showed Erdoğan’s approval rating rise to 48 percent in October 2019, up from his lowest approval rating since 2016.58 Yet an internal poll conducted by the CHP showed that 46 percent of CHP voters either disapproved of the Syria operation or were undecided.59 The CHP has starkly different proposals for Turkish foreign policy toward Syria — support for negotiations with Assad being one major point of divergence.

Nonetheless, the majority of the opposition parties — including a new parties forming under former top AKP lieutenant Ali Babacan and former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu — are pro-military and either adhere to Kemalist nationalism or MHP-style nationalism influenced by the more extremist ideology of the ultranationalist Grey Wolves. As a result, the AKP, the MHP, and the Iyi Parti have all criticized the CHP’s limited alliance with the HDP. The HDP and the Iyi Parti share only one political objective: the removal of Erdoğan and the ending of his party’s hold on power. It remains unclear what policies the new parties headed by Davutoğlu and Babacan will employ to attract nationalist voters without breaking up the opposition.

While the CHP has struggled to maintain its alliance with the HDP, it has also seemingly condemned itself to future political oppression in parliament by supporting measures used against the HDP that have transcended party lines. In September, in an ominous display of what the lifting of immunity and political purges could mean for the rest of the opposition, the CHP’s provincial branch leader was sentenced to 10 years in prison.60 Three months later the first CHP mayor was arrested in Urla, İzmir over allegations of connections to FETÖ — the acronym used by state authorities to refer to Fethullah Gülen’s movement. Opposition members saw this latest ruling as an attempt to punish the CHP and İmamoğlu without explicitly targeting the popular new mayor. With the immunity of the leader of the CHP on the line, it remains to be seen how far Erdoğan’s supporters in parliament will go to pursue members of the opposition beyond the HDP. Nevertheless, the opposition continues to gain from the defections of former AKP members despite incongruent ideologies. While the HDP has struggled internally to develop a new strategy and maintain relevance in the face of heavy-handed political oppression, former leader and enduring Kurdish icon Demirtaş is still hopeful. From jail he issued a statement in November 2019 that emphatically declared that the HDP would “continue its struggle together with all opposition.”61 For now though, his fate, and that of the HDP as a whole, seem to hang in the balance.

"The AKP’s targeting of the HDP has significantly changed the outlook for the opposition in the upcoming 2023 elections. Beyond the loss of HDP representatives ... the degradation of the HDP and the division of the Kurdish vote have created several ideological divides between the opposition parties."

Endnotes

- “HDP'nin gündeminde sine-i millet var,” En Son Haber, November 15, 2019.

- “Turkish public tired of elections, says opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu,” Ahval, August 13, 2019.

- Zülfikar Doğan, “Turkish opposition energised as ruling party's troubles deepen” Ahval, September 18, 2019.

Diego Cupolo, “Amid growing crackdown, pro-Kurdish party calls for new elections in Turkey,” Al-Monitor, November 20, 2019. - “Turkish parliament approves motion on Iraq, Syria,” Hurriyet, October 9, 2019.

- “Kayapınar ve Bismil belediyeleri önünde toplanan kitleye müdahale,” Mezopotamya Ajansi, October 21, 2019.

- Dimitri Bettoni “Gezi and the HDP: a Wedding Never Celebrated,” Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, June 15, 2015.

- Tim Arango and Ceylan Yeginsu, “Erdogan’s Governing Party in Turkey Loses Parliamentary Majority,” The New York Times, June 7, 2015.

- “Turkish gov’t, HDP herald ‘new phase’ in Kurdish peace process,” Hurriyet, December 22, 2014.

- “HDP’s Demirtaş: I'm not a manager, member, spokesperson, or sympathizer of PKK,” Birgun, January 8, 2017.

- “Turkey seeking up to 142 years in jail for co-head of pro-Kurdish opposition party,” DW, January 17, 2017.

- Carlotta Gall “Erdogan’s Most Charismatic Rival in Turkey Challenges Him, From Jail,” The New York Times, July 31, 2018.

- “Court issues fifth prison sentence for former HDP co-leader Yüksekdağ,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 8, 2017.

- Court issues fifth prison sentence for former HDP co-leader Yüksekdağ,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 8, 2017.

- “Turkish police investigate Kurdish leaders, fire water cannon at protesters,” Reuters, October 10, 2019.

- Douglas Frantz “Top Turkish Candidate Barred From Election,” The New York Times, September 21, 2002.

- “Factbox: Turkey's history of banning parties,” Reuters, May 3, 2010.

- “Factbox: Turkey's history of banning parties,” Reuters, May 3, 2010.

- Ceylan Yeginsu “Turkish Parliament Approves Stripping Lawmakers of Their Immunity,” The New York Times, May 20, 2016.

- Gulsen Solaker, “Turkish opposition backs immunity bill that Kurdish MPs say targets them,” Reuters, April 1, 2016.

- “Turkey passes bill to strip politicians of immunity,” Al-Jazeera, May 20, 2016.

- “HDP’s Demirtaş: I'm not a manager, member, spokesperson, or sympathizer of PKK,” BirGun Daily, January 8, 2017.

- “Anayasa Mahkemesi Karari” June 3, 2016.

Dilek Kurban “Think twice before speaking of constitutional review in Turkey,” Hertie School, February 20, 2018. - Kareem Shaheen “Turkey Arrests Pro-Kurdish Party Leaders Amid Claims of Internet Shutdown,” The Guardian, November 4, 2016.

- “Istanbul Besiktas Turkey: Stadium blasts kill 38 people,” BBC News, December 11, 2016.

- Daren Butler and Tuvan Gumrukcu “Turkey detains 235 over Kurdish militant links after Istanbul blasts,” Reuters, December 11, 2016.

- “Chronology for Kurds in Turkey,” Minorities at Risk Report, 2004.

- “Turkey Detains Hundreds Over Alleged PKK Links, Targeting HDP,” Financial Tribune, February 15, 2017.

- “Turkey: Hundreds detained over alleged links to PKK,” Al-Jazeera, February 14, 2017.

- Alper Atalay “Meclise yeni dokunulmazlık dosyaları sevk edildi,” Anadolu Ajansi, May 20, 2019.

- “HDP il ve ilçe binalarını basan polis, panolara bayrak astı,” Haber Sol, November 26, 2019.

- “Pro-Kurdish MP detained as Turkish cops break up protest,” IPA News, July 9, 2019.

- “Armed attack on pro-Kurdish party headquarters in Istanbul,” Ahval, January 15, 2020.

- “Pro-Kurdish HDP equivalent to outlawed terrorist PKK, says Erdoğan,” Ahval, February 3, 2019.

- “Huge blast targets cops, Turks clamp down on social media,” CBS News, November 4, 2016.

- Jared Malsin “This Man Has the Toughest Job in Turkey,” Time, November 11, 2015.

- Yvo Fitzherbert “'No peace, no future': In Turkey, HDP arrests fuel Kurdish discontent,” Middle East Eye, November 22, 2016.

- Selahattin Demirtas “I’m in prison. But my party still scored big in Turkey’s elections,” The Washington Post, April 19, 2019.

- Selahattin Demirtas “I’m in prison. But my party still scored big in Turkey’s elections,” The Washington Post, April 19, 2019.

- "Support HDP political prisoners," HDP America.

- “The Trustee Regime In Turkey & Denial Of Right To Vote And Right To Be Elected (31 March- 20 November 2019),” HDP America, December 21, 2019.

- Tom Stevenson “Turkey-PKK fighting revives bad memories,” DW, September 9, 2015.

- “20 belediyeye kayyum atandı: 2 milyon 219 bin yurttaşın iradesi yok sayılıyor,” Mezopotamya Ajansi, November 14, 2019.

- “The Trustee Regime In Turkey & Denial Of Right To Vote And Right To Be Elected (31 March- 20 November 2019),” HDP America, December 21, 2019.

- Karwan Faidhi Dri “15 HDP mayors removed, dozens put behind bars since Turkish local elections in March: rights group,” Rudaw, November 4, 2019.

- Cenay Babaoğlu “Mayors vs Municipal Councils: Can Turkey's Local Governments Reach a Consensus?,” The New Turkey, August 20, 2019.

- “The Trustee Regime In Turkey & Denial Of Right To Vote And Right To Be Elected (31 March- 20 November 2019),” HDP America, December 21, 2019.

- For Kurds in southeast Turkey: the urban conflict continues,” IPP Media, July 25, 2018.

- Umar Farooq “Fear in Turkey's old city of Diyarbakir, despite multi-million reconstruction,” Middle East Eye, March 30, 2017.

- “Mayor in Diyarbakır’s old city detained,” Hurriyet, December 20, 2019.

- “For Kurds in southeast Turkey: the urban conflict continues,” IPP Media, July 25, 2018.

- “Mardin Belediyesi'ni 620 milyon borçla devraldı,” T24, April 19, 2019.

- Nurcan Baysal, “Kurdishness forbidden under state-appointee rule,” Ahval, April 11, 2019.

- Nurcan Baysal, “Kurdishness forbidden under state-appointee rule,” Ahval, April 11, 2019.

- “Turkey imposed 369 curfews in Southeast in last 4 years: report,” Turkish Minute, July 1, 2019.

Nino Kandelaki, “Roadblocks in Turkey’s Southeast Turkey Strategy: An Analysis,” Bellingcat, July 3, 2019.

Deniz Tekin “Security force vehicles killing civilians with impunity in southeast Turkey,” Ahval, August 13, 2019. - Gregory Waters, “Between Ankara and Damascus: The role of the Turkish state in north Aleppo,” The Middle East Institute, June 20, 2019.

“Türkiye Serêkaniyê ve Girê Spî'ye kaymakam atadı,” Mezopotamya Ajansi, December 6, 2019. - “From İmamoğlu to Erdoğan: Who's the terrorist?,” Mezopotamya Ajansi, September 2, 2019.

- Umit Ozdal “Turkey ousts three Kurdish mayors for suspected militant links, launches security operation,” Reuters, August 18, 2019.

- Ali Kucukgocmen, Tuvan Gumrukcu, and Orhan Coskun “Turkey’s Syria operation reveals cracks among Erdogan’s political foes,” Reuters, November 12, 2019.

- Ali Kucukgocmen, Tuvan Gumrukcu, and Orhan Coskun “Turkey's Syria operation reveals cracks among Erdogan's political foes,” Reuters, November 12, 2019.

- Ezel Sahinkaya “Turkey's Opposition Leader Faces 10 Years in Prison on Terror Charges,” VOA News, September 7, 2019.

- “Jailed Kurdish politician Demirtaş: 'We continue our struggle together with all opposition',” Ahval, November 19, 2019.

Photos

- Election flags displaying the image of the imprisoned Selahattin Demirtas, presidential candidate and leader of People's Democratic Party (HDP), in Ankara, on June 19, 2018. (Photo by ADEM ALTAN/AFP via Getty Images)

- Turkish anti-riot police officers block People' Democracy Party's (HDP) headquarters as HDP members call a protest against Turkey's "Olive Branch" operation in Syria on January 21, 2018 in Diyarbakir. (Photo by ILYAS AKENGIN/AFP via Getty Images)

- Ekrem Imamoglu (C,R), the new mayor of Istanbul from Turkey's main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), shakes hand with the removed mayor of Mardin, Ahmet Turk (L) during his visit on August 31, 2019, in Diyarbakir. (Photo by ILYAS AKENGIN/AFP via Getty Images)

- People's Democratic Party (HDP) co-chairs Selahattin Demirtas (R) and Figen Yuksekdag hold a press conference about an explosion targeting a cultural center in Suruc district of Sanliurfa in which at least 31 people were killed and 100 others injured, on July 20, 2015, in Ankara, Turkey. (Photo by Dilek Mermer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

- Turkish police officers detain former pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democracy Party (HDP) parliamentarian, Sebahat Tuncel (C) on November 4, 2016 during a demonstration outside Diyarbakir's courthouse. (Photo by ILYAS AKENGIN/AFP via Getty Images)

- Supporters of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democracy Party (HDP) flash victory signs during a demonstration on October 30, 2016 in Istanbul, following the arrests of the two co-mayors in Diyarbakir. (Photo by OZAN KOSE/AFP via Getty Images)

- Turkish anti-riot police officer stand guard in front of the Peoples Democracy Party (HDP) headquarters, in Istanbul on August 19, 2019 during protests in the streets of the city. (Photo by OZAN KOSE/AFP via Getty Images)

- Supporters of imprisoned Selahattin Demirtas, Presidential candidate of People's Democratic Party (HDP), hold HDP flags and their lit mobile phones in the air during an election campaign in Istanbul on June 17, 2018. (Photo by YASIN AKGUL/AFP via Getty Images)

About the author

Kayla Koontz is a recent graduate from UC Berkeley’s Global Studies MA Program and former researcher at the UC Berkeley Human Rights Center. She received her B.A. in International Relations with a minor in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies from San Francisco State University in 2016. She has studied and worked in Turkey and her past research has focused on Kurdish insurgent groups and Turkish foreign policy.

About the Middle East Institute

The Middle East Institute is a center of knowledge dedicated to narrowing divides between the peoples of the Middle East and the United States. With over 70 years’ experience, MEI has established itself as a credible, non-partisan source of insight and policy analysis on all matters concerning the Middle East. MEI is distinguished by its holistic approach to the region and its deep understanding of the Middle East’s political, economic and cultural contexts. Through the collaborative work of its three centers — Policy & Research, Arts & Culture and Education — MEI provides current and future leaders with the resources necessary to build a future of mutual understanding.