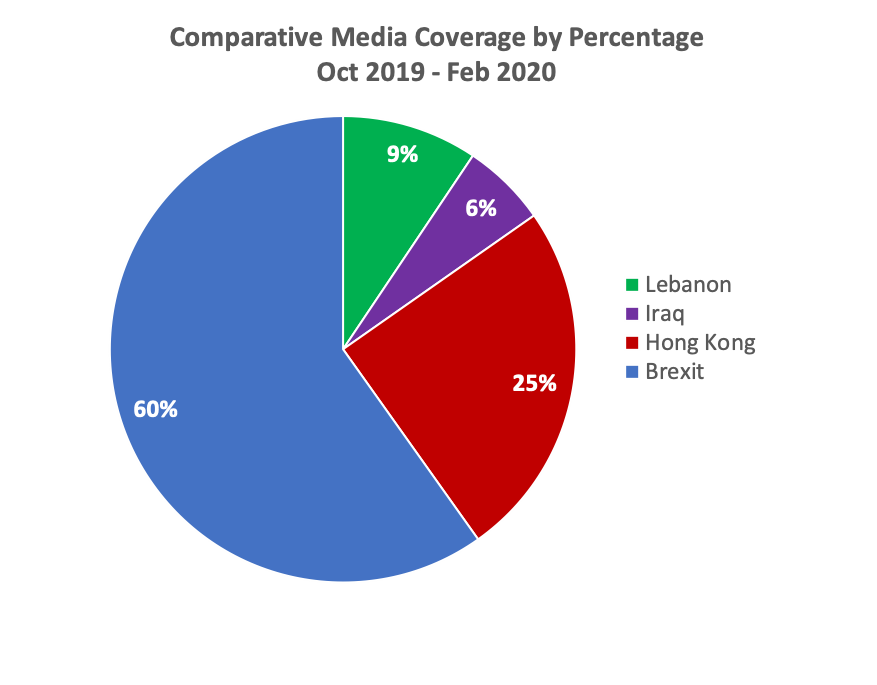

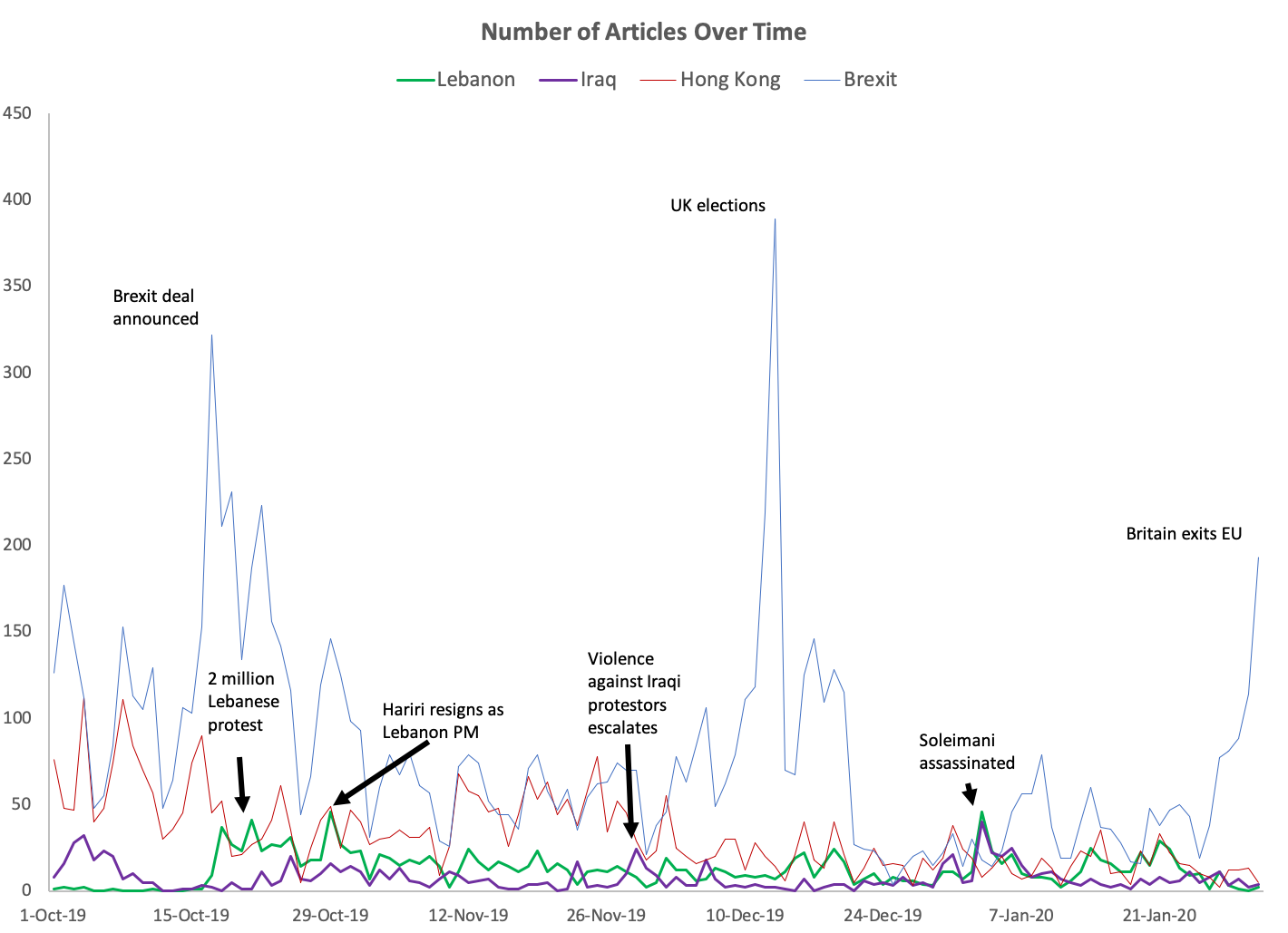

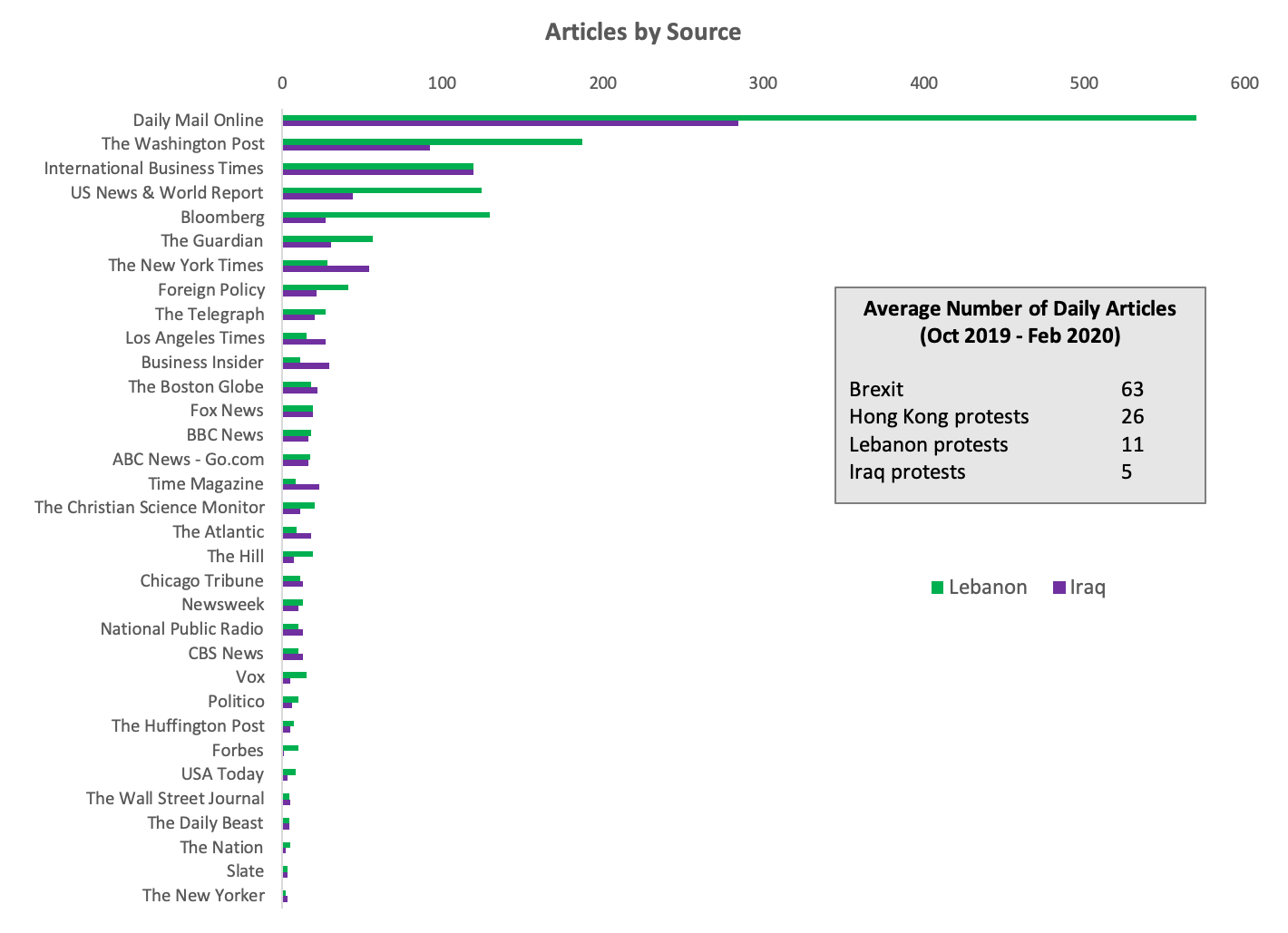

Lebanese and Iraqi protesters have faced an uphill battle drawing global media attention since Arab Spring-like uprisings erupted in both countries last October. As illustrated in all three charts, coverage of the protests has been dwarfed by other major international news stories running concurrently with the uprisings, such as Brexit and the Hong Kong protests.

The main implication of low coverage has been a lack of sustained international pressure on Lebanese or Iraqi political leaders to accommodate protester demands for wholesale systematic changes. The risk of keeping the spotlight away is that it allows political actors to push the limits of their response, and in Iraq’s case, violent retribution has resulted in at least 600 people killed since protests began.

Domestic focus in US and UK limiting coverage of international stories

It also amplifies the shortcomings of the global media industry. While U.S. and U.K. media continue to wield considerable influence in shaping global discourse, the inward political shift in both countries in recent years has resulted in a drop in coverage of important international stories, as evident in Figure 1. The Lebanese and Iraqi protest movements had little chance contending in newsrooms with the Trump impeachment trial and Brexit.

Lebanon and Iraq may have received more global attention had their uprisings erupted in tandem with the Arab Spring of 2010/2011, with the United States and Britain relatively stable domestically, and greater media bandwidth for international news. But editors at major American and British outlets, with dwindling editorial resources and their primary audiences fixated on domestic issues, are faced with a delicate triage process that is today resulting in fewer high-profile media spots for international stories.

And the simultaneous eruption of anti-establishment protests in Chile, Lebanon, Iraq, and Hong Kong — while heralded in some circles as the beginning of a globalized mass movement — actually resulted in each protest movement competing for the limited space awarded to international stories, further pushing down coverage. As shown below in Figure 2, Hong Kong protests received significantly more international coverage before the Lebanese and Iraqi uprisings began, effectively forcing global newsrooms to split limited coverage between the protest movements. Neither protest movement detracted, however, from the resources devoted to covering Brexit, which remained the focus of global editors as well as their audiences in North America and Europe.

Missed coverage, missed opportunities for US policy

U.S. foreign policy has been notably minimized in the Democratic presidential primary campaigns, and almost entirely absent from the debate stage. The lack of American public interest in challenges beyond their shores, however, does not diminish the immense U.S. influence in various parts of the world. The United States is a major stakeholder in the happenings in Lebanon and Iraq, and, as I’ve written, possesses enough power to make or break the protest movements.

But U.S. foreign policy, much like its domestic policies, is a cog in a system that’s deeply entrenched in decades of bureaucratic rigidity and firmly established special interests. U.S. policy toward both Lebanon and Iraq has been framed within a narrow obsession of countering Iranian influence. But the rigidity of U.S. policy has actually been counterproductive to its own interests.

The American approach in Lebanon, for example, has remained constant for four decades — supporting the same local political allies who have cantankerously co-governed the country with Iran’s local allies, all of whom are now the target of protests. The U.S. approach in Iraq has been purely militaristic — as exemplified by the assassination of Qassem Soleimani in the midst of popular anti-Iranian protests, effectively jeopardizing the grassroots uprising by precipitating a fierce crackdown by Iranian-backed militias.

Media coverage on Lebanon and Iraq is currently set in reactionary mode, responding to events dictated by U.S. actions. The assassination of Soleimani, for example, was the peak moment of coverage on Lebanon and Iraq, as shown in Figure 2.

An absence of media coverage means there’s an absence of the necessary evaluation of U.S. policy in both countries that may actually serve U.S. interests. America’s haphazard response to the protest movements speaks of policy stagnation — a clear inability to shift gears from decades-old policy and take advantage of an opportunity to further objectives. Without a focused media proactively and openly putting forth policy alternatives, and elevating audience interest, there is little incentive for U.S. bureaucrats to change course. The result: a missed opportunity.

Media must change the narrative about the Middle East

Journalists and editors at major media outlets have privately expressed to me the difficulties of conveying the intricacies of foreign stories to domestic audiences. Indeed, explaining to an American audience Lebanon’s horribly complex sectarian consociational political system, and which foreign power backs which local group, and that local groups co-govern despite hating each other, but they coordinate to ensure they each take a slice of the financial pie and enrich themselves while running the economy into the ground … no, it’s not an easy story to sell.

But there is a broader narrative that requires a shift in how grassroots activists represent their issues, and how major media outlets tell the Middle Eastern story. Both the Arab Spring of 10 years ago, as well as the protest movements today, depict a Middle East that differs vastly from how the region is so frequently portrayed to international audiences.

The popular uprisings expose the reductiveness of limiting the Middle East to a set of geopolitical rivalries or ancient sectarian feuds that create an illusion of exceptionalism divorced from political experiences closer to home. As far as many ordinary citizens of the Middle East are concerned, there’s very little difference between the royal families of the Gulf, the Iranian mullahs, and the secular dictators of the Arab republics. They all participate in the degradation of the region, the repression of civilians, and the denying of economic opportunity and dignity. The aspirations and frustrations of the people of the Middle East mirror the trends seen in developed nations — widespread resentment toward powerful elites that have taken too much and created intolerable daily hardships for the majority. This is the narrative that is undertold, and one that strikes a familiar chord with American and European audiences.

Methodology

Data was compiled from Meltwater, using keyword searches between October 1, 2019 and January 31, 2020. The 34 outlets listed comprise major media outlets in the United States and Britain to indicate trends in global media coverage. While there is a margin of error in exact figures using Meltwater data — as its web crawls may not detect each relevant article or, conversely, capture adjacent news stories — the overall data accurately reflects the trends as depicted in this article.

Antoun Issa is a non-resident scholar at MEI and senior editorial manager at Atlantic 57. Issa is a frequent commentator on Middle Eastern affairs and previously worked as a journalist in Beirut between 2011 and 2015. He has written extensively on the region for numerous media outlets, including the Guardian, Washington Post, and Foreign Policy. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by ANWAR AMRO/AFP via Getty Images