On July 23, 2022, the Iran-backed Houthi militia attacked the residential neighborhood of Zaid al-Moshki in Taiz, one of Yemen's most populous cities, killing one child and injuring 11 others, most of whom were under the age of 10. The attack, which drew U.N. condemnation, was particularly troubling given the U.N.-brokered truce that went into effect on April 2. The continued violence in this southwestern city underscores the Houthis' lack of commitment to peace and unwillingness to comply with the terms of their agreement regarding Taiz.

The Houthi militia, a militant group that overthrew the internationally-backed government of Yemen in September 2014, has immersed the country in a civil war that has dragged on now for nearly seven years. The Saudi-led military intervention that began in March 2015 has worsened the political and humanitarian situation on the ground and plunged Yemen into a wider regional conflict. Given the asymmetrical nature of the civil war and the Houthis' ongoing military activity, they have been able to consolidate their hold over most of the cities in the north of the country by force with the help of military and financial support from Iran.

Taiz, Yemen’s third largest city, has been systematically blockaded and attacked by the Houthi militia since 2015. The siege has suffocated the city, caused mass displacement and starvation, and resulted in thousands of deaths. U.N. humanitarian aid personnel have been denied access to Taiz, making U.N. officials acutely aware of the need to find a swift solution to the violence to help local residents. But the issue is unlikely to be resolved in the near future, as the Houthis have realized that the blockade is an effective way to extract concessions from Yemen's government and improve their bargaining position.

The U.N. truce, extended most recently on August 2 for two months, was conceived of as a way to ultimately get to peace talks. This first component of the truce required building confidence between the warring parties in preparation for any subsequent negotiations. In addition to a nationwide and broader regional ceasefire, the Houthi militia requested that Sana'a airport be reopened and fuel tankers be allowed entry to the militia-held port of Hodeida as preconditions to accepting the truce. In turn, the Houthis were expected to open critical roads around Taiz to help improve humanitarian conditions in the besieged city.

While more than 8,000 passengers have been able to travel to Amman and Cairo from Sana’a airport per the agreement, and 26 ships have entered the port of Hodeida, the Houthis have rejected a U.N. proposal to open several roads in Taiz, including three that they themselves requested and one suggested by civil society. The Houthis' refusal to reopen the roads in Taiz for the second time since the U.N.-brokered Stockholm Agreement in December 2018 is an example of their broader unwillingness to surrender control over any territorial gains they have made in the country — and certainly not through negotiations.

The Siege of Taiz

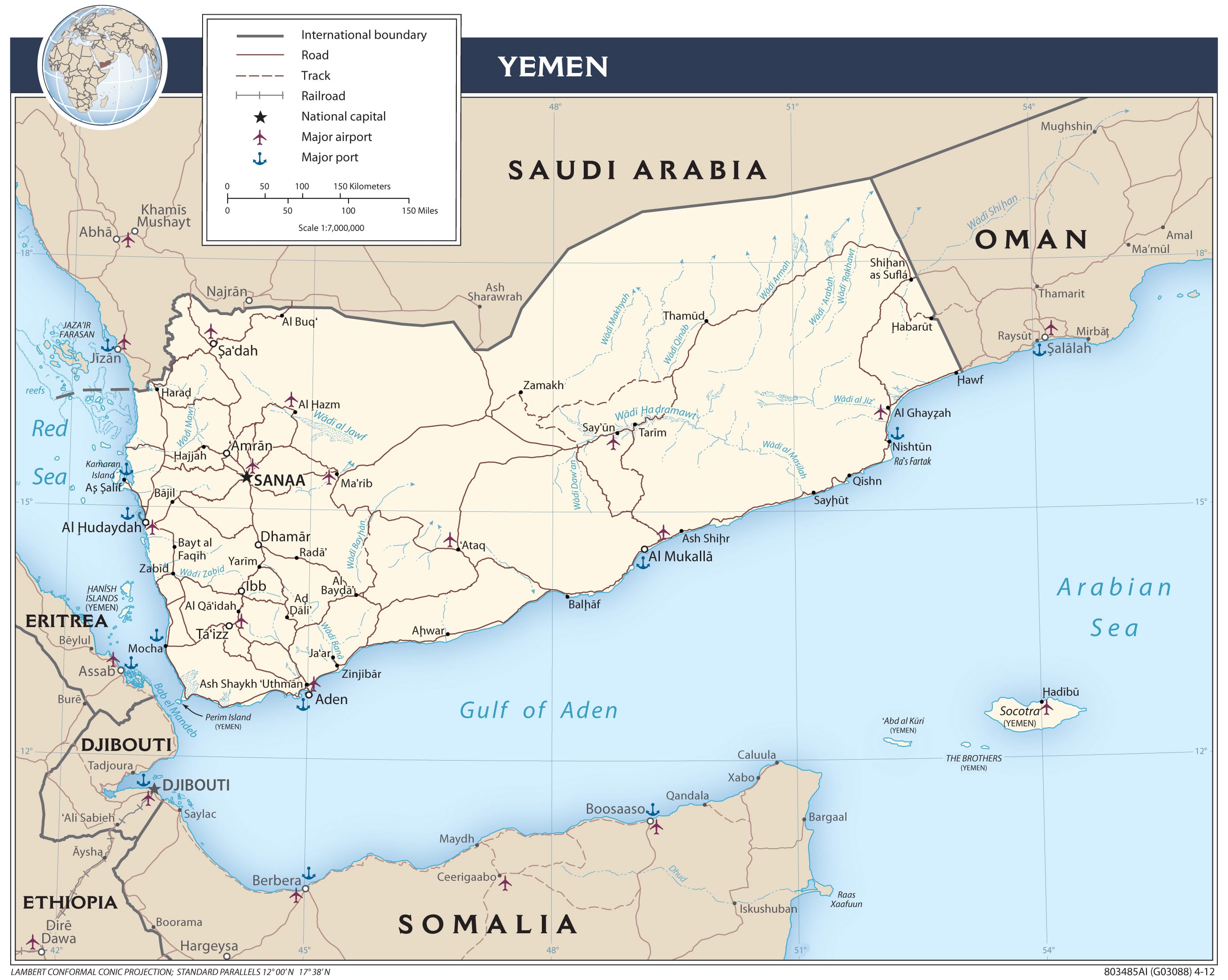

The city’s geography has made it uniquely vulnerable to blockade. The southwestern part of the city lies at the junction of two crucial highways that residents use regularly, one running east-west toward Mocha and the other running north-south toward Sana’a via the governorates of Dhamar and Ibb. With a high population density and a landlocked terrain, Taiz has become trapped. Water reserves have been slowly run down and are now either extremely limited or depleted altogether, and residents have had to rely on water trucks from outside the city as a critical lifeline. Militiamen and snipers control access to Taiz through checkpoints, with homes and apartment buildings located just on the other side.

The fighting has displaced over 270,000 Taizi residents, according to non-government monitors. Those who have decided to stay in the city, often for lack of an alternative, have been forced to adapt to road closures and find alternate means to get to their destinations. Local negotiations have been temporarily effective — the siege around Taiz was partially lifted in August 2016, for example — but to date, there has been no lasting solution.

Due to the treacherous terrain surrounding Taiz, the Houthis’ closure of the main roads has choked the city, causing prices to skyrocket and resulting in deaths. Journeys that used to take less than 10 minutes, such as the trip between Taiz city and al-Hawban, now take five or six hours on rugged mountainous roads. Prior to the conflict, residents used three main roads to travel in and around the city, while a fourth one was used as a last resort.

- The eastern entrance to the city: This was one of the main roads used before the conflict. It links up with Hawban and Gawlat al-Qasr, which are the main roads that connect the city with the governorates of Ibb and Dhamar, all the way to the capital, Sana'a.

- The northern entrance: This links rural areas together through Ussaifara Road, the 60-meter road, and al-Siteen Street. It is considered a major road that connects the city with the rural areas north of Taiz Governorate, such as Khalaf Sharaab and other densely populated areas.

- The northeastern entrance: This is the third entrance to the city, through the 40-meter road (al-Arbaeen Street), which connects the Rawdah area in the city center toward the wholesale market, as well as the Kalabh area toward the Sofitel hotel.

- The Western entrance: This connects the city through the ghee and soap factory area, and runs from Taiz toward Mocha and then on to the coastal governorate of Hodeida on the Red Sea.

In addition, there are secondary roads outside of Taiz that residents previously used as alternatives but the Houthis have also closed. After the onset of the conflict and the Houthi-imposed blockade, people were compelled to find other ways of getting around, including dangerous mountainous roads. Residents have also reported the dangers posed by Houthi landmines planted on outlying roads, which often shift during heavy rainfall. These landmines have claimed the lives of a number of people, especially children, throughout the conflict.

Within the context of the truce, the Houthis’ continuous refusal to open the main roads that have been used by civilians for decades is irrational. The primary concern for the Houthis is that unblocking them will lead Yemen’s army to mobilize in Taiz and attempt to take back Sana’a. This is a farfetched scenario as Taiz city mainly houses a civilian population that lacks adequate security infrastructure beyond unorganized militias1 belonging to Yemen’s Islah party, who are largely focused on securing their own neighborhoods and interests. Mobilizing to enter Houthi-controlled territory would require a monumental effort on part of the Saudi-led coalition and would prompt a backlash from the international community similar to what happened in 2017 when the coalition was intent on entering Hodeida. Given the fact that the Yemeni government has agreed to allow ships to enter and flights to depart from Houthi-controlled areas as a humanitarian measure, the Houthis have a real opportunity to demonstrate good faith by opening the main roads around Taiz. Instead, they have proposed alternatives, such as opening other roads that would be entirely under their control. This is unnecessary since there are already established roads that could be used safely for travel.

It is worth noting that the U.N. has incorporated Houthis’ demands on opening the roads, which the Yemeni government reluctantly accepted. According to the U.N., “The latest UN proposal called for three roads put forward by the Houthis, officially known as Ansar Allah, and one advocated by civil society. The Government accepted the proposal and the Houthis rejected it.” U.N. Special Envoy to Yemen Hans Gundberg and the EU have both called for the Houthis to reconsider the proposal: “The EU deeply regrets a rejection by the Houthis of the latest proposal by UN Special Envoy (UNSE) on road reopening notably around Taiz.” However, the Houthis’ official media channels reported the lack of progress on Taiz as a failure of the Yemeni government to accept their conditions, presenting a false narrative about what actually happened given the official U.N. and EU statements.

Understanding the Humanitarian Impact of the Houthis' Siege of Taiz

In 2015, U.N. Under-Secretary for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Stephen O'Brien said in a statement that, "Al-Houthi and popular committees are blocking supply routes and continue to obstruct the delivery of urgently needed humanitarian aid and supplies into Taiz City.” The U.N. reported that their humanitarian aid trucks — en route to deliver life-saving services for residents of Taiz — were “stuck at checkpoints and only very limited assistance” was allowed in. In October 2015, Houthi forces intercepted three trucks sent by the World Health Organization and confiscated medicine intended for hospitals in central Taiz.

Non-government organizations have decried the situation as well. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Taiz has consistently ranked as the deadliest governorate in Yemen, mainly due to the siege by Houthi forces. Following a directive from their commanders, Houthi supervisors at checkpoints have prevented the entry of humanitarian goods into the city, including water, food, and gas, as international humanitarian organizations have reported.

The siege has divided Taiz into two different areas: one in Taiz city, which is more or less politically independent under the government of Yemen, with a majority of residents who are affiliated with the Islah party, and the other in the Hawban area, which is now under the control of the Houthi militia. Hawban contains major factories for food and other resources that serve the whole country and is considered an economic powerhouse for the city.

The siege of Taiz has further complicated access to health care, particularly for residents living in the Hawban area under Houthi control. It used to take 15 minutes to access a hospital from this part of the city; it now entails a journey of several hours. The siege has also led to complications in health services due to the complexity of delivering vaccines into the city, while access to specialized treatment, including dialysis, has become extremely difficult.

Moreover, the Houthis have imposed an illegal tax, collected at checkpoints, on both commercial tankers and local citizens. This tax, on top of existing transportation and rising fuel costs, has caused an increase in the price of food and basic essentials. Transportation fares for travelers have increased significantly as well, putting a tremendous economic burden on residents and making Taiz one of the most expensive cities to live in all of Yemen. All of these issues are increasing peoples’ vulnerability to price shocks as well as the likelihood of a regional famine.

In particular, the road closure has disproportionately affected women. Due to customary and societal restrictions as well as the current situation, women are unable to travel long distances. Some women2 have stated that the Houthis have required them to have a male guardian to pass through checkpoints. Such requirements impose a significant burden on women and increase the expenses and transportation fees that they must shoulder. For women living on the front lines of the conflict3 in villages like al-Shaqab, there are additional challenges as well: They are forced to remain at home until fighting subsides and have to walk alongside roads at night to avoid fire in order to access relief materials. The road closures have also prevented working women from caring for their children.4 Due to increased travel times and distances from their homes to their jobs, many have had to stop working altogether.

Similarly, access to education has also been restricted, as students cannot reach their schools and universities inside the city. Some workers have lost their jobs due to the blockade, either because they feared crossing the militia-monitored roads during the conflict or because their salaries were not sufficient to cover the cost of transportation. Psychologically, there has been tremendous pressure on anyone traveling through checkpoints controlled by gunmen.5

The Houthis' blockade of Taiz is widely viewed as a deliberate and systematic policy of starvation targeting their opponents. The blockade has sown divisions and deepened mistrust of both the Houthi militia and opposing parties among the city’s residents. It has also created a significant backlash against Yemen's government and the U.N. due to their inability to take decisive action concerning the reopening of the roads. In addition, Taizi residents have become very angry and frustrated with the Saudi coalition and especially the UAE for their failure to secure the city and liberate it from the Houthi militia like they helped Aden. In particular, Islah party affiliates believe that their political affiliation is the reason why the UAE has not provided the same level of support in Taiz.

UN Effectiveness on the Taiz Issue

At the time of the Stockholm Agreement, Taiz had the most reported fatalities since fighting began in 2015. A total of 19,000 deaths were reported between 2015 and 2018, and more than 2,300 fatalities resulted from the direct targeting of civilians by the Houthi militia. The U.N.'s progress report on the Stockholm Agreement one year on stated that, "Taiz represents a critical area of the Stockholm agreement where there needs to be much greater focus and attention on mediating agreements between the parties to de-escalate hostilities and to open sustainable humanitarian corridors to alleviate the suffering of the inhabitants of Taiz.” To many this was seen as an indirect admission of the U.N.'s failure to impact the trajectory of the Taiz issue.

The Stockholm Agreement did not provide a vision or recommendations on how the Taiz issue should be resolved. It also did not learn from the failure of previous arrangements, like the Dhahran al-Janoub initiative, in which the warring parties established a preliminary work plan around opening the roads in Taiz that was never implemented.6 Instead, the Stockholm Agreement’s expected outcome was for the warring parties to meet and set up a mechanism to do so. Therefore, it was no surprise that this poorly conceived plan did not deliver any result regarding de-escalation. The Houthis' policy of starvation and siege of civilian areas — a clear violation of international law — continued with impunity as no measures to protect civilians from these crimes were enforced, even after the Stockholm Agreement.

Opening the roads to commercial trucks and transport vehicles would significantly ease the suffering of Taiz’s residents; by cutting transportation costs, it would reduce the prices of essential commodities, including food, water, and medicine, and make it easier for local residents to get around.

In the 2022 truce, the U.N. has floated a proposal to open the roads, which both civil society and the government of Yemen have asked for during "an initial round of discussions" to help facilitate aid deliveries and the movement of residents. The U.N. office was reasonably confident7 that this proposal would move forward, given that the Houthis' preconditions of reopening the airport and allowing the entry of oil tankers to Hodeida have now been met. The U.N. reported that the Houthis had agreed to reopen some critical roads around Taiz and hoped that this would be a "collective victory for Yemen."

However, despite initially signaling that they would reopen critical roads in Taiz by the end of the second truce extension on June 1, the Houthis blocked an agreement at the end of May after three days of U.N.-sponsored talks in the Jordanian capital. The Houthis' tactic of initially engaging with U.N. talks, only to disengage at a later stage, has so far outplayed all other parties in the process, including the U.N. envoy’s office. The inability to extract a deal from the Houthis over the areas under their control stems from their belief that they are the sole entity responsible for dictating policy in these areas. This points to the U.N.'s powerlessness when it comes to having an impact on the militia, as it needs to remain diplomatic in the face of the Houthis' intransigence lest the entire process become stalled.

The Houthis are continuing to raise the ceiling of their demands and set unreasonable conditions, such as insisting that government security forces leave Taiz before they will lift the siege. The U.N. has seen progress in the military commission that met in Amman, comprising military representatives of the government of Yemen, the Houthis, and the coalition’s Joint Forces Command. The parties agreed to meet to build trust and form a joint coordination room that will be tasked with de-escalating incidents at the operational level, but unilateral statements from the Houthis demonstrate that not everyone is on the same page as they see all other parties as violating the terms and conditions.

However, the military committee still needs to be better organized to take action and resolve issues related to opening the roads in Taiz as well as ceasefire violations. The intensity of shelling and attacks vary from month to month, but so far the truce has not been able to benefit the residents of Taiz. During the truce period, Houthi military build-ups along local roads foreshadowed an escalation, one in May and the other in July. As the Houthis maintain complete control of the city and prevent reporters from entering, violations are intensifying.

Part of the problem is that the Houthis see the conflict as one between them and the region, which means that ceasefire and truce initiatives are always viewed as a cessation of hostilities against Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and vice versa. The Houthis will need to demonstrate that they are willing to compromise on domestic issues if they are to gain any credibility in any upcoming political settlement. For now, evidence suggests that they seem to view any agreement they reach regarding the territory and citizens under their control as a means to strengthen their hold and regroup militarily. None of this demonstrates a readiness to engage in agreements yet.

What Can the UN Do?

There is no shortage of interest from the U.N. about Taiz or concern for the civilian lives affected. The U.N. understands firsthand the impact of this siege and has highlighted it repeatedly. However, there are limits to what the U.N. can achieve given the fact that Taiz is under the control of more than one unofficial authority. Unfortunately, the Houthis’ lack of flexibility has thwarted U.N. efforts and impeded progress on opening the roads and improving conditions under the blockade. Even high-level officials have not been spared from being denied entry to the city by the Houthis, including the U.N. humanitarian affairs commissioner. Most importantly, the U.N has been unable to enforce a truce and prevent Houthi militia violence against the residents of Taiz.

It has been particularly frustrating for residents of the city to see the U.N. making progress on all agenda items on the Houthis’ list without making any significant progress in Taiz. Taha Saleh, a local journalist who has been involved in covering the road issue, expressed concern over the stalled process: “As a citizen from Taiz, I see that opening the airport in Sana’a without opening the roads in Taiz as a fundamentally imbalanced humanitarian standard.” He added, “As citizens from Taiz, we are not asking to travel abroad, we just want to cross the roads safely to get to our city and hospitals.”8 At this point, it is irrational to expect that the U.N. will be able to make headway with the Houthi militia in the face of continuously stalled and fruitless negotiations. Even the truce extension, despite the lack of commitment from the Houthis, foreshadows a greater difficulty at the end of the process.

To make any political and humanitarian gains on Taiz, several obstacles need to be overcome:

- In any U.N.-brokered ceasefire initiative, the U.N. must first focus on stopping the violence in Yemen and then that in the region to disabuse the Houthis of the notion that the conflict is only regional in nature. All parties to the conflict that have militias or troops on the ground, including the Saudi-led coalition, must ensure that no offensive measures are taking place inside the country. Defensive measures need to be effectively communicated and incidents thoroughly investigated.

- The Saudi-led coalition should push for talks on Taiz and ensure that this issue is high on its agenda. The international community should also understand that this is a humanitarian measure that should not be tied to any political talks and push for the roads to be reopened regardless of whether or not there is a truce. In addition, the U.N. should attempt to push the Houthis to reopen existing roads instead of creating new ones that the residents of Taiz have never used before.

- It is important to demonstrate progress by implementing something on the ground rather than getting bogged down in meetings that produce no tangible results, as has happened so far in more than one process. This is especially important when the U.N is being seen as successful in implementing Houthi demands but not government ones.

- The U.N. can include a provision for the parties to accept upfront limited sanctions in the event of non-compliance because as it is, there is nothing that holds any party accountable for their obligations.

- Given the high risk that new roads will be used to fortify military positions, the U.N. must ensure that none of the roads in Taiz are being opened for military reasons. Freedom of movement should be granted to residents of Taiz without fear of detention by any warring party.

- Finally, the U.N. must ensure that the Houthis are willing to engage in talks without harming Yemeni civilian opponents. More specifically, it must ensure that the Houthis do not expand their siege of the city and further harm civilians — or else the cycle of violence risks erupting again.

Opening the roads in Taiz is first and foremost a humanitarian issue that will drastically improve people’s lives. The Houthi militia has a unique opportunity to prove its good faith by opening existing roads and guaranteeing the safety and security of the travelers using them. If there is any potential for broader future talks, all of the parties to the conflict will first have to prove that this is possible in Taiz.

Fatima Abo Alasrar is a Non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute and a Senior Analyst with the Washington Center for Yemeni Studies. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Endnotes

1. Zoom interview with a Yemeni woman residing in Taiz, December 12, 2021.

2. Zoom interview with a female student living in Taiz, June 23, 2022.

3. Interview with a civil society organization member who used to live in Taiz, currently residing in Turkey, June 23, 2022.

4. Interview with a teacher from Taiz, July 7, 2022.

5. One of the women interviewed on this subject in a focus group discussion in August 2021 described the psychological impact: “My experience of going anywhere was bitter, as two of my children who were accompanying me were assaulted by the Houthis at one point and they were trying to take them. After begging and pleading, they let us travel.” Another one stated, “I feel suffocated at the idea of taking the road to do anything because what used to take me minutes now takes hours in unpredictable conditions.”

6. According to a respondent who was interviewed for this report, the representatives that met were able to come to an agreement verbally but there was no subsequent implementation.

7. Meeting with a representative from the Office of the U.N. Special Envoy in Amman, Jordan, June 11, 2022.

8. Zoom interview with Taha Saleh, Yemeni journalist who resides in Taiz, August 10, 2022.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.