That George W. Bush made an enormous error by invading Iraq in 2003 is finally generally accepted by most national security analysts, regional specialists, and historians in the United States and around the world. Steve Coll, the writer, has now contributed another book that details the history of Iraqi-US relations. He has, however, also rewritten a piece of the story that requires a correction for the sake of historical accuracy.

In The Achilles Trap (Penguin, 2024), Coll casts doubt on whether Iraqi intelligence had actually tried to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush (41) in Kuwait in April 1993. The importance of the 1993 Kuwait plot is the role it may have played in shaping President George W. Bush’s (43) animosity toward Saddam Hussein and Bush’s decision to invade Iraq 10 years after the attempt on his father.

If the Kuwait plot were a fabrication, it would fit yet another brick in the wall of many well documented falsehoods and misunderstandings that led to the calamitous US invasion. Unfortunately for that allegation, the plot was very likely to have been quite real.

To hear Coll tell the tale, two weeks after Bush (41) visited Kuwait, Kuwaiti security services “announced the arrest” of the plotters. The Kuwaiti authorities, Coll writes, told the US ambassador but never mentioned it before to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Secret Service, or Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Moreover, two Americans who subsequently had access to Iraqi archives found no mention of such an Iraqi plot.

Coll concedes that there was a bomb-laden truck and that the bomb apparatus did bear the unique hallmarks of an Iraqi intelligence truck bomb. Perhaps, he muses, this Iraqi truck bomb was one the Kuwaitis had found abandoned when they reclaimed their country. He suggests the Iraqis had left behind a fully assembled truck bomb two years earlier, and the brilliantly devious Kuwait security services had kept it all that time and were using it in 1993 as evidence to mislead the FBI, CIA, and Secret Service.

The late Sandy Berger, then-Deputy National Security Advisor, allegedly had doubts and, according to Coll, the decision on whether and how to respond dragged on for weeks. President Bill Clinton, in the Coll telling, had a last-minute change of heart and ordered that the US retaliatory attack be changed from a daytime strike to a night-time raid that would produce fewer Iraqi casualties.

That version of history suffers from selective sourcing, incomplete research, and a bias that comes from forcing history to support a theory. My reason for such a strong assertion derives from knowledge I have as a result of leading the Clinton White House effort to analyze what had happened in Kuwait in April 1993. Here, then, is what I recall:

The Kuwaiti government, far from announcing anything, had hoped to keep the story of the Iraqi plot to kill Bush under wraps. News of the plot did, however, leak out, but only in an obscure Arabic-language newspaper in London.

The US government in those days paid people to read and summarize even such obscure journals. Their reports were, however, seldom widely read. At the time, I was assigned to the White House National Security Council as Special Assistant to the President for Global Affairs, a portfolio that included counter-terrorism. Earlier, as Assistant Secretary of State, I had been deeply involved in the First Gulf War, and so stories about Kuwait still attracted my attention. The report of the plot on Bush (41) was buried in my message traffic and would normally never have caught my eye, but it was a Sunday, and I usually dedicated Sunday mornings to skimming the kinds of reports that I missed reading during the week.

Upon reading the report, I made four secure calls. The first three were to senior officials at CIA, FBI, and Secret Service. The fourth was to the US Ambassador to Kuwait, Ryan Crocker. The calls all revealed the same result: the obscure article in the London paper had not attracted their attention, and they had no knowledge of any attempted attack on Bush (41). Crocker and I agreed that he would ask the Kuwaiti Interior Minister, which he did the next day.

The Kuwaiti official told Crocker that the Kuwaitis saw the plot as an embarrassment to them and a stain on the otherwise successful celebration of Bush (41) in the nation he saved by conducting the First Gulf War. They wanted to keep the story quiet. In response to Crocker’s report, I gained concurrences to instruct him to ask the Kuwaitis to cooperate with US investigators from Secret Service, CIA, and FBI, all of whom would be arriving in Kuwait.

In late April 1993, National Security Advisor Anthony Lake ordered up two separate, parallel investigations and analyses. The first was to be conducted by CIA, the second by FBI. CIA experts examined the truck bomb on April 29. FBI forensics personnel arrived a week later and returned in June for further investigation.

According to an unclassified FBI report,

On June 2, 1993, representatives of the FBI, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and others in the Department of Justice (DOJ) discussed the results of their investigations with representatives of the Clinton Administration. Three weeks later, the DOJ and CIA reported their conclusions. The DOJ and CIA reported that it was highly likely that the Iraqi Government originated the plot and more than likely that Bush was the target. Additionally, based on past Iraqi methods and other sources of intelligence, the CIA independently reported that there was a strong case that Saddam Hussein directed the plot against Bush.

Parts of the detailed CIA report have been declassified, including its bottom line: “a confident analytic conclusion that Iraqi President Saddam Husayn directed his intelligence service to assassinate former President Bush during Mr. Bush’s visit to Kuwait on 14-16 April […] alternative scenarios against which the evidence was tested are implausible.” The report goes on to discuss forensics, interviews, and intelligence sources. While the section on intelligence sources is redacted in the declassified document, following the retaliation, a senior CIA official briefed The Washington Post that CIA was “highly confident that the Iraqi government, at the highest levels, directed its intelligence service to assassinate former President Bush.”

Following the CIA and FBI meeting with me on June 2, the reports had been finalized over the next two weeks and then briefed by CIA Director Jim Woolsey and Attorney General Janet Reno to Anthony Lake and the other Principals (Warren Christopher, Les Aspin, Colin Powell, Leon Fuerth). There were two meetings with the President, who grilled us on the evidence and on what would be an appropriate retaliatory response. President Clinton decided in the meeting on June 23 on the retaliatory strike, which took place three days later.

The delay in US decision-making from April to June had not been one of agonizing doubts, it was a period of professional investigation and analysis by two teams, intentionally kept separate from each other, one of law enforcement experts and one of intelligence community members. No one in any meeting I attended, including Sandy Berger, found fault with the conclusions of the two reports. Nor did Berger ever express any doubts about the reports’ conclusions to me, his coordinator on the project. (Berger did, however, always take it upon himself when important decision were being made to be the one who asked 20 questions, who reviewed every possibility. It was one of his many great strengths.)

When President Clinton made the decision on the US retaliation, I was tasked to coordinate a very small interagency team to implement it. The decision had from the start been to strike the Iraqi intelligence center in Baghdad and to do so at night.

Why then did two distinguished Americans later find no record of the plot in the Iraqi archives, as Coll notes? The archives are extensive and are still partially unexplored. Moreover, evidence would have been in the Iraqi intelligence ministry, and it was that building that the United States blew up in retaliation for the Kuwait plot. Moreover, as the fallacy goes, the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence.

And what of the bomb-laden Iraqi truck that was perhaps in Kuwaiti hands for two years, armed but left behind by departing Iraqi forces, according to Coll’s speculation? The CIA report makes clear that the truck had originally belonged to the Kuwaiti Ministry of Water and was one of many vehicles retreating Iraqi forces had taken with them into Iraq. It was not an Iraqi truck bomb found upon liberation but a Kuwaiti truck stolen just before liberation and subsequently in Iraqi government hands for two years.

Does all of this matter now, 30 years later? None of it changes my conclusion that Bush (43) made what was perhaps the greatest foreign policy and national security mistake in the history of the United States.

None of it really contributes to our understanding of the degree to which Bush's (43) decision was based in part on personal animus against Saddam Hussein. There may, however, be a graduate student decades hence wondering if all the evidence of Iraqi venality was just a fabrication, and I want to send her a message: There was a lot of fabrication and misunderstanding leading to US and Iraqi decisions in the 1990s and early 2000s, but I believe the Iraqis did try to kill Bush (41) in Kuwait in April 1993, despite what you might read elsewhere. And I believe a close reading of the evidence and good research will lead you to that conclusion too.

Richard A. Clarke is a former Chair of the Board of Governors of the Middle East Institute. He was Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence in the Reagan Administration, Assistant Secretary of State for Politico-Military Affairs in the Bush (41) administration, and Special Assistant to the President and National Coordinator for Security and Counter-terrorism in the Clinton and Bush (43) administrations.

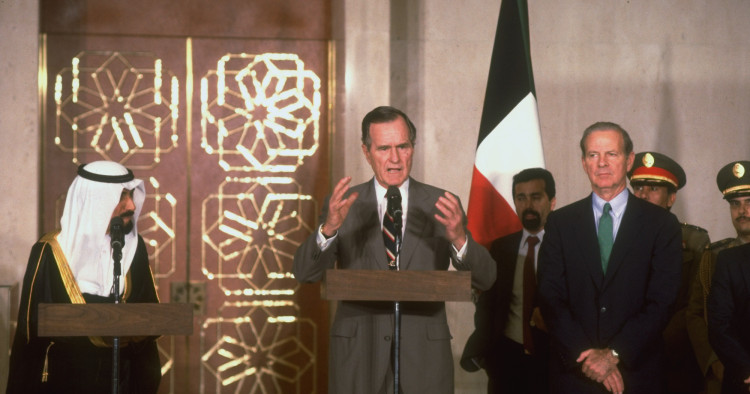

Photo by Diana Walker/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.