The prospect of a peace deal between Saudi Arabia — the custodian of Islam’s two holy mosques, one of the world’s 20 largest economies, and the most important international energy producer — and Israel, America’s closest ally in the Middle East, has understandably captured the imagination of many, including the president of the United States. Saudi recognition of Israel would pave the way for other Arab and Muslim-majority countries to follow suit. It could help end decades of Arab-Israeli strife, integrate the Jewish state into the economies of the region, and form the cornerstone for a new regional alignment aimed at containing Iran.

However, after Hamas’s unprecedented attack against Israel on Oct. 7, the siren song of Saudi-Israeli normalization risks wrecking the US-Saudi relationship against the rocks of stubborn geopolitical realities. So why is US President Joe Biden still insisting on wagering a historic breakthrough in US-Saudi relations, one conceived to counter growing Chinese and Russian influence in a vital part of the world, on such a highly improbable outcome?

The current governing coalition in Israel is the most right-wing in the nation’s history, the country remains locked in a war with Hamas that most Israelis view as existential, the Palestinians are hopelessly divided, and US administration officials will increasingly have to shift their attention to a tightly contested presidential election.

Under current circumstances, it is therefore very unlikely Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will prove willing and able to agree to Saudi Arabia’s prerequisites for normalizing relations, namely a durable cease-fire in Gaza and Israel’s acceptance of a credible, nonreversible pathway toward the creation of a Palestinian state.

Meanwhile, Riyadh and Washington are on the verge of clinching a broader and tremendously consequential pact, even when measured against the impact of Saudi-Israeli normalization. The “mega-deal,” as it’s being referred to, is a game changer on a global scale. It is a wide-ranging strategic alliance designed to fend off Chinese and Russian encroachments in a region that has ceased to be the exclusive realm of the United States. It would firmly bind the kingdom, a globally influential middle-power, and a regional heavyweight, to the US for decades to come.

Senior Saudi officials described to me what is being negotiated as an exclusive marriage contract. It follows years of an open relationship, whereby the US engaged in intrigues with regional rival Iran, while Saudi Arabia expanded its ties to China and Russia.

The written understandings, which are now in the final stages of drafting, cover a wide array of strategic interests, including a mutual defense agreement, civil-nuclear cooperation, artificial intelligence, and long-term collaboration on energy. They would pull Saudi Arabia further into American-led global coalitions, such as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII) and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), both founded to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and that country’s growing economic clout.

Premising a crucial US-Saudi alliance on the fate of an embattled Israeli prime minister and the complexities of Israeli-Palestinian peace-making amounts to diplomatic malpractice. The potential blowback from the collapse of US-Saudi talks, after having come so close, would cause considerable and enduring damage to US strategic interests.

Although the US is the dominant partner, Saudi Arabia has options. It can pursue a civil-nuclear program with a strategic competitor, precluding the US from maintaining oversight and presenting a potential nuclear proliferation risk. It can deepen its investments in key Chinese industries, including artificial intelligence and defense. It can also undermine the primacy of the US dollar by selling its oil in non-dollar currencies, including the Chinese yuan.

But both President Biden and Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham, who has championed Saudi-Israeli normalization, still publicly insist that any US-Saudi deal will require Senate approval. This, they argue, necessitates Saudi recognition of Israel in order to secure enough pro-Israel votes in Congress’ upper chamber. The premise of their argument is flawed.

There is, in fact, a pathway to clinching a US-Saudi deal that does not require the Senate’s formal consent. President Biden could offer Saudi Arabia a written defense commitment modeled on the Comprehensive Security Integration and Prosperity Agreement (C-SIPA), which his administration concluded with neighboring Bahrain only seven months ago, in September 2023. Senior US diplomats explain to me that this is “the closest you can get to a NATO Article Five mutual defense treaty without the need for Senate approval.”

C-SIPA would significantly upgrade the current relationship by committing both countries to working together to deter and confront any external aggression against the territorial integrity of the other. It would also necessitate working together at the highest level to deter and confront any type of external attack, including missile strikes, such as the ones Iran and its proxies employ against the kingdom.

President Biden could additionally declare Saudi Arabia a Major Non-NATO ally, a designation that would facilitate the sales of advanced American military equipment, and which was bestowed on neighboring Qatar a few years ago. The complexity and slow pace of America’s arms acquisition process has been a major source of frustration for the Saudis, who can often buy Chinese alternatives “off the shelf.”

Similarly, the joint venture on a civil-nuclear program, which would pour billions into America’s moribund nuclear industry, can also proceed without the need for a Saudi-Israeli normalization deal or Senate approval. The two parties would defer, but not necessarily reject, a decision on Saudi Arabia’s request to enrich its own uranium. In the meantime, with US assistance, the kingdom can establish its own uranium conversion plant and begin developing the know-how needed to manage a major nuclear program.

This less-for-less approach may not give the Saudi leadership and President Biden all they had wished for, but it offers tangible and achievable progress, and it precludes the risk of imploding the relationship under the burden of unrealistic expectations created by an all-or-nothing strategy. In fact, despite public denials, a senior US official privately conceded that, instead of a Senate-ratified agreement, the administration could “take significant steps down the path toward an agreement, and maybe be ready to do more to complete the process the following year.”

President Biden and Sen. Graham do not need to give up on their quest for Saudi-Israeli peace. If regional dynamics become more conducive for a bigger and better “mega-deal,” Riyadh will still have a strong incentive to pursue peace in return for a more iron-clad, Senate-ratified defense treaty and the ability to enrich its own uranium.

Rather than wagering on the improbable, now is the time for President Biden to seal a bilateral US-Saudi agreement that will help secure America’s strategic interests versus its global competitors for decades to come.

Firas Maksad is a Senior Fellow and Senior Director for Strategic Outreach at the Middle East Institute.

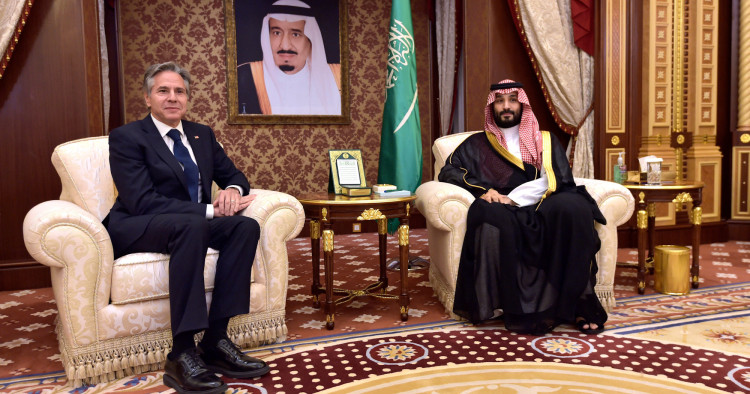

Photo by AMER HILABI/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.