This essay is part of the series “All About China”—a journey into the history and diverse culture of China through essays that shed light on the lasting imprint of China’s past encounters with the Islamic world as well as an exploration of the increasingly vibrant and complex dynamics of contemporary Sino-Middle Eastern relations. Read more ...

China’s outbound capital policy is an attempt to reforge the Middle East in its own economic likeness through a revised ‘Going Global’ geoeconomic macro policy. China-Iran oil trade is only the beachhead of a deeper economic integration agenda, yet the geoeconomic management institutions that are currently forming will define China-Iran and wider China-Middle East engagement for decades to come.

China’s demand for Iran oil is only one side of a geoeconomic game that takes in multiple stake-holders in nuclear energy, advanced manufacturing, offshore distributed manufacturing zones, and global trade routes.[1] Iran’s dependence on China for oil exports may be problematic for Iran, but for China, the relationship represents a multiplex of institutional and policy opportunities.[2]

China’s wider foreign policy in the Middle East is still emerging, however the institutions surrounding the Iran-China oil trade are already well advanced. Macro geopolitical rhetoric will continue to be delivered in terms of ‘civilization-to-civilization’ Athens Forum dialogue. However the geoeconomic institutional realities are more sobering than this affectation.[3]

Iran-China oil trade is a long-term institutionalized project that is likely to remain quietly stable through the 2020 oil price volatility.[4] And while the China-Iran geoeconomic relationship is often seen from outside as geopolitics in the extreme, the institutional realities are more pragmatic with fewer hyberbolic foreign policy soundings from the domestic China perspective.[5]

‘International Capacity Cooperation’ (ICC) has been the guiding trade, industry and investment strategy of China for the past five years, while ‘Going Global’ has been around for over 20 years. Often though, both terms remain vague macro policies that Central government can shovel big ticket institutions, enterprises, loans and projects into, and out of, at will.

But the China Petroleum International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance gives us a first glimpse of what a concerted China state geoeconomic presence in a host economy would look like. It is useful because it is a reasonably permanent institution, and it is interesting because the results of this public administration experiment are reasonably replicable across other Belt and Road host economies.

Who runs China’s Iran oil policy?

The overarching bilateral framework for petroleum cooperation between the two states was established under the Long-term agreement on crude oil trade between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Iran treaty, signed on March 17 2002.[6] The treaty provides for at least 12 million tons of crude oil export annually.

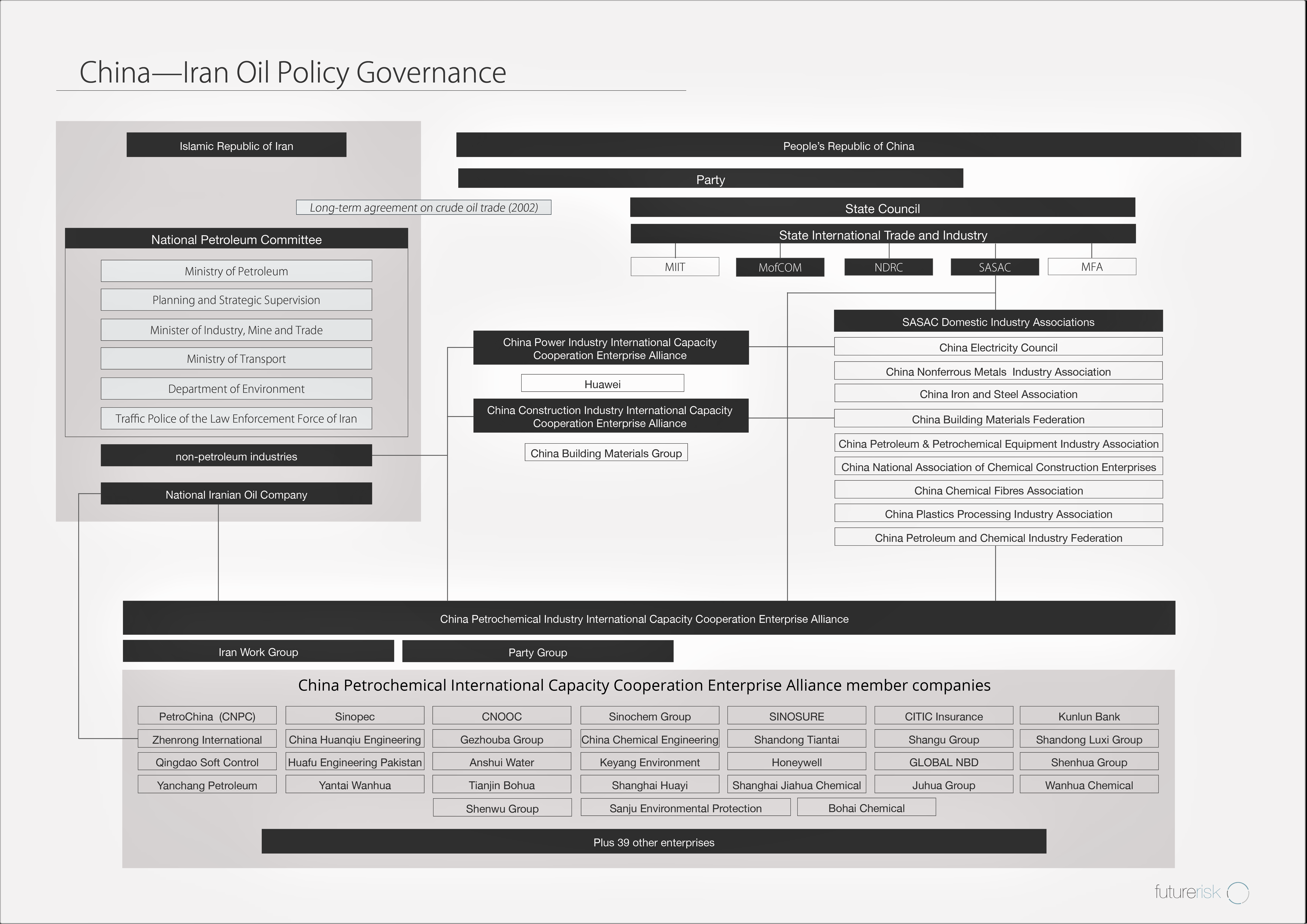

In order to implement the agreement, overcome various stages of sanctions and to integrate China’s Iran policy with China’s wider ‘Going Global’, ‘International Capacity Cooperation’, and ‘Belt and Road’ foreign policies, a variety of institutions have developed to manage the China-Iran petrochemical policy relationship.

The most recent, and important, of these institutions is the China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance (ICC Petrochemical Industry Alliance) established in 2016.[7] [8]

The ICC Petrochemical Industry Alliance consists of seventy major petroleum and chemical SOEs and semi-private enterprises, led by China’s ‘Big Three’ oil producers PetroChina (the listed arm of China National Petroleum Corporation), Sinopec and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). [9] [10] Other China enterprises under the ICC Petrochemical Industry Alliance include financial, insurance, chemical, and construction enterprises, including a mix of national and local government SOEs and pseudo-private capital.

China has established ICC Enterprise Alliances for all the major industries. There are ICC Industrial Enterprise Alliances for electric power, steel, non-ferrous metals, construction, light industry, mining, and shipbuilding. These are sectoral groupings that allow entire industrial chains to coordinate policy activity as a single institution, across a range of China’s external economies. They are also obviously easily directed by Party/State economic policy agencies.

Figure 1. China’s Iran Oil Policy Institutional Framework.[11] [12] All the ICC Enterprise Alliances are basically broad supply-side cartels, 50-to-100 huge companies organized together to operate under one policy direction in external economies. The international operations of China’s domestic industry federations had previously operated as buy-side cartels, attempting to control the prices of commodities that came into China, such as attempts to control iron ore prices by China Iron and Steel Association.[13] But this new set of institutions is mostly concerned with establishing manufacturing bases abroad and thus are better understood in terms of trying to cartelise the supply-side.

All the ICC Enterprise Alliances are basically broad supply-side cartels, 50-to-100 huge companies organized together to operate under one policy direction in external economies. The international operations of China’s domestic industry federations had previously operated as buy-side cartels, attempting to control the prices of commodities that came into China, such as attempts to control iron ore prices by China Iron and Steel Association.[13] But this new set of institutions is mostly concerned with establishing manufacturing bases abroad and thus are better understood in terms of trying to cartelise the supply-side.

In general, China does not need to employ a national level energy security council or to coordinate petroleum importing activities at the national economy level, because it has national State-owned Enterprises. These can fulfil the state bureaucratic agenda directly. Now with these national ICC Enterprise Alliances, the Party-State can even more easily coordinate sectoral industrial Going Global operations in external economies.

These ICC Enterprise Alliances institutionally intersect with wider Party-state geoeconomic policy in two ways. The first major institutional intersection for the ICC Petrochemical Industry Alliance is a horizontal integration with the other sectoral ICC Enterprise Alliances. The second is the retrospective integration with the domestic industry associations which had previously organized the same domestic industrial enterprises. There is also an extreme amount of personnel crossover between the two types of industry association — domestic and international.

The new ICC Enterprise Alliance institutions are formed on the basis of the domestic industrial association system. These correspond to similar industries — cement, steel, aluminium, electricity, light industry etc and function as vice-ministerial bureaucratic agencies, meaning their heads are only one step away from top China Communist Party (CCP) positions in State Council or Party agencies.

On the China side, the ICC petrochemical enterprise engagement in Iran runs through some key people at the Party-State-enterprise level. These personnel are often wearing multiple hats: an enterprise hat, a Party position, a state policy position, and now also an ICC Enterprise Alliance position.

For example, Pang Guanglian is concurrently deputy Secretary General of the domestic industry association, the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation (CPCIF). He is also on its Party Group Standing Committee, is vice chair of CPCIF’s International Exchange and Foreign Enterprise Committee and is also now Secretary General of the new ICC Petrochemical Industry Enterprise Alliance.[14] [15]

Pang is the industry leader for China’s hydrocarbon and chemicals sector, and on the ongoing trade war with the US and growing Iran economic integration, has argued that a greater decoupling between China and the US in the global economy is now inevitable. He has also been touting market reforms in the downstream retail end of China's oil and gas sector.[16]

Similarly, Li Shousheng is Chairman of CPCIF, and also Chairman of the Petrochemical ICC Enterprise Alliance.[17] Li is also a sitting member of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission Party Group, and an independent non-executive director of China National Petroleum Corporation. Li also heads the recently established China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Artificial Intelligence Alliance.[18]

SASAC Party Group is one of the highest Party positions in China, while being on the board of CNPC is one of the highest enterprise positions in China. Li has said explicitly that the aim of the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance is to coordinate the structure of ICC activities along Belt and Road economies and to directly guide foreign cooperation activities, including between China and Iran.[19]

In the institutional makeup of the ICC Enterprise Alliance, the enterprise side is just as important as the Party-State side, with many provincial government SOEs and some pseudo private capital enterprises participating in the alliance.[20] Significant enterprise-level personnel in the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance include Ms. Wang Xinge General Manager of China Huanqiu Engineering.[21]

There is clearly a lot of institutional translation from the old industry federation system.[22] Another example is Mr. Zeng Jian who is both CPCIF Party Group vice secretary and executive vice chair of the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance.[23] But also within the institutions itself, already established as being cross-sectoral, cross-governmental and interrelated with policy and politics, are intersectional leading groups, or committees, which provide policy guidance to the alliance.

For example the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance has an ‘Iran Work Group’.[24] This group is periodically policy-driven by top level design such as the Notice regarding the publication of the Regulations on the Work of the Iranian Working Committee of the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry International Capacity Cooperative Enterprise Alliance (Consultation Draft).[25] The policy prescriptions from which are outlined below.

Figure 2. Institutional functions of the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance’s Iran Work Group.[26]

The leading groups within this ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance are important policy nstitutions in designing and implementing China’s state policy on oil trade with Iran. Analysing this legal-bureaucratic approach to China’s economic institutional engagement with the global economy in general, and Middle Eastern economies in particular, will be increasingly important to understand as China emerges into a second-round of globalisation.

Indian Ocean Trade War dynamics

Iran cooperation is critical to China’s land and sea Eurasian trade and investment infrastructure.

China has developed a range of trade, logistics, investment, and external industrial policies which explicitly define Iran as a strategic geoeconomic partner. These include investment in the Iran rail network development, the Caspian Sea Trans-Caucasus logistics route, the Chabahar port development, and the Tehran-Istanbul rail link as part of the Lapis Lazuli Road. These are all trade and investment strategies which can develop alongside an industrial capacity transfer policy which is ultimately aimed at shifting China’s production of infrastructure inputs to Central Asia, the Middle East and East Africa.

This geoeconomic gravity has clear political displacement implications for the region. China has no incentive to follow US sanctions against Iran except where it might attract sanctions upon itself. For Iran, China is its largest export market for crude oil and the Iran-China oil trade has continued despite the recent round of sanctions.[27] [28] While China’s customs data statistics show imports of Iranian oil dropping, China is widely understood to have simply moved trade onto Iran owned-vessels on the export side and obfuscated reporting on the import side.[29] [30] [31]

The previous sanctions regime under the Obama administration had punished the major China-Iran state-owned oil trader, Zhuhai Zhenrong. The latter company had been the key China SOE charged with fulfilling China’s oil policy in Iran and was tasked to fulfil the 2002 long-term agreement as China’s client partner with the National Iranian Oil Company.[32] As per the treaty, Zhenrong had consistently imported 12 million tons of crude oil from Iran annually since 2002 until it stopped reporting in 2010.

Zhuhai Zhenrong was sanctioned by the Obama administration, but its institutional persistence means it is probably directly named in the long-term supply treaty with Iran. Another long-term supply treaty with Iran, for refined fuel, is brokered by a different arm of the company, Tianjin Zhenrong. While the new ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance names one member as Zhenrong International. Zhenrong had been one of the initial central SOEs under the jurisdiction of central SASAC when it formed in 2003. However the ownership and institutional structure of Zhenrong transformed in 2015, and is now unclear.[33] [34]

The Meng Wanzhou sanctions case also aligns with the ICC Enterprise Alliance structure. Meng was arrested in Canada over Huawei’s alleged breaking of Iran sanctions.[35] Huawei is a member of a different alliance, the Electric Power ICC Enterprise Alliance. Batteries are huge business for the China SOE, and for the alliance, power engineering projects have been a vanguard ICC industry in Iran. [36]

The work of each ICC Enterprise Alliance then clearly intersects with the work of the others. Power equipment for example is a key node in the ICC strategy and the ICC Power Enterprise Alliance has obvious institutional and policy synergies with petrochemicals [37] If we analyse the ICC Petrochemical Enterprise Alliance as a supply-side cartel, then what do ten sectoral ICC Enterprise Alliances working together mean?

China-Iran investment and trade is not simply oil. In 2015, the launch year of ICC, Chinese enterprises in Iran signed contracts worth $1.52 billion. In 2016 the agreements were expanded into an umbrella $600 billion 2016-2025 investment project. Iran has since become a major market for China's overseas exports of engineering, technology and complete sets of equipment — in essence a host economy for the transfer of China’s factories.

In the wake of the US sanctions on Iran in 2019, China upgraded this 2016-2025 geoeconomic relationship by adding an additional $400 billion to the investment package, of which $280 billion would go directly to Iran’s petrochemical industry, and $120 billion to other key ICC manufacturing sectors.[38]

While in other ICC economies in Central Asia and Eastern Europe China is transferring a lot of industrial capacity in low-end manufacturing, there is a concerted effort in Iran, and other Middle East economies, to transfer high-value-added factories, in nuclear and new energy equipment, satellite communications and agribusiness machinery.

ICC is an industrial capacity transfer policy that aimed to transplant brownfield China domestic production into greenfield investment. However, there are very few success stories to point to in either China’s global policy or in the Middle East. It remains to be seen whether potential BRI Eurasia-Africa investments can really replace China’s existing Pacific trade.

And while much of the institutional inertia has been set in motion, the branding of these activities as ‘ICC’ is being wound back. At a central Ministry of Commerce level, the ‘ICC’ branding is being retrofitted back to the ‘Going Global’ policy rhetoric. The ICC Enterprise Alliances will seemingly keep their titles, as will the ICC sovereign wealth funds. [39] So the policy name cannot simply be erased from China’s institutional economic history. But expect a lot more ‘Going Global’ rhetoric in English as ICC 2.0 policy language is backtracked to Going Global 1.0.[40]

China’s wider Persian Gulf game

China’s industrial investment strategy in the Middle East economies is really part of a wider ‘Middle East-Africa wing’ of its global ‘International Capacity Cooperation’ policy.[41] There are huge opportunities for Middle East economies to catch some cheap industrial transfers and unaudited public debt as clean capital investment. But there are also geopolitical risks.

China is speeding up institutional integration and narrative construction around ‘Eurasianification’.[42] However, for China, the Middle East is a necessary problem, rather than a goal in itself. From a hard-line realist international relations perspective, China’s geoeconomic and geostrategic purposes would be much better served if the Middle East simply did not exist. If China could have an Indian Ocean port on the edge of Xinjiang with which to access new industrial transfer developments in East Africa, this would serve China’s geoeconomic policies much better.

In geopolitical reality though, China’s Central Asia-Middle East-East Africa International Capacity Cooperation strategies all coalesce in Iran as China’s land bridge to the Belt and Road economies in Europe and ocean access to the Middle East and East Africa trade, industry and investment policy ambitions.

Ultimately, China’s trade and investment agenda in the Middle East is one of imports back in to China. And the Iran-China hydrocarbon trade will be a good indicator of how the rest of China’s Middle East development strategy and future trade logistics networks develop. China as an importer is an under-valued analytical framework in China’s ‘New Era’ economic model, as the ‘China as exporter to the world’ dogma was so firmly established under the reform era model.

Naturally, strengthening geoeconomic ties with Iran serves internally coherent economic goals. But China building a maritime sphere of influence in the north-western Indian Ocean is impossible to ignore. China in the Middle East is a new global economic dynamic. And China’s long-term institution building in Iran is a vanguard of China’s wider Indian Ocean geoeconomic policy.

[1] Zahid Khan & Changgang Guo, “China’s Energy Driven Initiatives with Iran: Implications for the United States,” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 11, 4 (2017): 15-31, DOI:10.1080/25765949.2017.12023315.

[2] Daniel Markey, “Why Iran’s dependence on China puts it at risk,” OUP Blog, March 16, 2020, https://blog.oup.com/2020/03/why-irans-dependence-on-china-puts-it-risk/.

[3] People’s Republic of China Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Athens Declaration on the establishment of the Ancient Civilizations Forum,” April 24, 2017, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/t1457694.shtml.

[4] Tsvetana Paraskova “Saudi Arabia’s oil price war Is backfiring,” Oil Price, March 22, 2020, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Saudi-Arabias-Oil-Price-War-Is-Ba….

[5] John Calabrese, “China-Iran Relations: The Not-So-Special “'Special Relationship,’” China Brief 20, 5 (March 16, 2020), https://jamestown.org/program/china-iran-relations-the-not-so-special-s….

[6] “What is Iran’s protection policy for Chinese enterprises’ investment and cooperation?” Economic and Commercial Section of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Islamic Republic of Iran, November 19, 2017, http://ir.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ddfg/201711/20171102672655.shtml, treat is 中华人民共和国与伊朗伊斯兰共和国原油贸易长期协议).

[7] “China oil industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance formally established” (中国石油和化工行业国际产能合作联盟) ChemChina, September 14, 2016, http://www.chemchina.com.cn/portal/xwymt/hyxw/webinfo/2016/09/147726887….

[8] Lin Qi “China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Alliance established to support the globalization strategy of petrochemical companies,” Reuters, September 14, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/china-oil-chemical-alliance-0914-idCNKC….

[9] “China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance Holds Conference,” China Plastics Industry Network, November 11, 2016, https://www.su-liao.com/html/xinwen/xingyexinwen/2233.html.

[10] “'Three Oil Barrels’ led Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Alliance formally established,” Zhitong Finance, September 14, 2016, https://www.zhitongcaijing.com/content/detail/21103.html.

[11] “Unveiling ceremony and first working meeting of the Iran Work Committee of the China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance held at Huanqiu,” Sohu, December 18, 2017, https://www.sohu.com/a/211217746_825950.

[12] “Shanghai Guozhen one of 70 leading companies in the petroleum and chemical industry to jointly launch international alliance of International Capacity Cooperation enterprises,” Guoxun Goup, October 14, 2016, http://www.chinayie.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=23&id=2….

[13] David Stanway “One iron ore price spells more chaos in China market,” Reuters, March 2, 2010, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-ironore/one-iron-ore-price-spe….

[14] “Unveiling ceremony and first working meeting of the Iran Work Committee of the China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance held at Huanqiu,” Sohu, December 18, 2017, https://www.sohu.com/a/211217746_825950.

[15] “International spokesperson for the chemical industry—Pang Guanglian,” China Chemical Industry News, January 11, 2020, http://www.ccin.com.cn/detail/9c2a53e6ff0705cac2706e6f43e349ef.

[16] Yan Chunwing “Pang Guanglian, Secretary-General of China Petrochemical International Cooperation Enterprise Alliance: a new ballast stone for Sino-US relations,” China Chemical Industry News, March 23, 2020, http://www.ccin.com.cn/detail/5d35b5826baaa7842ef4fe897e7670ad.

[17] Notice on the publication of “Regulations on the Work of the Iran Working Committee of the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry International Capacity Cooperative Enterprise Alliance (Consultation Draft)” (关于公示《中国石油和化工行业国际产能合作企业 联盟伊朗工作委员会工作条例(征求意见稿)》 的通知 中石国合联外发 [2018] 001 号), China Petrochemical International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance, republished at Sohu, January 4, 2018, https://m.sohu.com/a/214616842_825950.

[18] Chen Chen & Han Qing (Eds.) “China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Artificial Intelligence Alliance Formally Formed” (中国石油和化工行业人工智能联盟工作领导小组) Shanghai People's Daily, September 21, 2017, http://sh.people.com.cn/n2/2017/0921/c134768-30759485.html.

[19] “Unveiling ceremony and first working meeting of the Iran Work Committee of the China Petrochemical Industry International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance held at Huanqiu,” Sohu, December 18, 2017, https://www.sohu.com/a/211217746_825950.

[20] “Shanghai Guozhen one of 70 leading companies in the petroleum and chemical industry to jointly launch international alliance of International Capacity Cooperation enterprises,” Guoxun Goup, October 14, 2016, http://www.chinayie.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=23&id=2….

[21] Regulations on the Work of the Iran Working Committee of the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry International Capacity Cooperative Enterprise Alliance.

[22] “Pan Guanglian,” China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation, http://www.cpcic.org/Data/View/1549.

[23] “China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation Vice Chair: Sino-US economic and trade friction has little direct impact on China’s petrochemical industry,” Economic Daily, June 1 2019, http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/gdxw/201906/01/t20190601_32240473.shtml.

[24] Notice on the publication of “Regulations on the Work of the Iran Working Committee of the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry International Capacity Cooperative Enterprise Alliance (Consultation Draft)” (关于公示《中国石油和化工行业国际产能合作企业 联盟伊朗工作委员会工作条例(征求意见稿)》 的通知 中石国合联外发 [2018] 001 号), China Petrochemical International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance, republished at Sohu, January 4, 2018, https://m.sohu.com/a/214616842_825950.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “As US sanctions increase, China remains Iran’s top crude, condensate importer,” S&P Global Platts, January 10, 2020, https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/0110….

[28] Dan Katz, “Despite sanctions, China is still doing (some) business with Iran,” Atlantic Council, October 1, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/despite-sanctions-chin….

[29] Economic and Commercial Section of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Islamic Republic of Iran, “Due to U.S. sanctions, China uses Iranian shipping to secure crude oil trade,” August 22, 2018, http://ir.mofcom.gov.cn/article/jmxw/201808/20180802778089.shtml.

[30] Ian Talley, Costas Paris and Courtney McBride “U.S. Sanctions Chinese Firms for Allegedly Shipping Iranian Oil Trump administration, facing tensions with Tehran, targets Cosco tankers,” Wall Street Journal, September 25, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-sanctions-chinese-firms-for-allegedly-….

[31] Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “China’s Declared Imports of Iranian Oil Hit a (Deceptive) New Low,” Bourse and Bazaar, October 23, 2019, https://www.bourseandbazaar.com/articles/2019/10/23/chinas-declared-imp….

[32] Chen Aizhu “China’s Iran specialist Zhuhai Zhenrong tips senior crude trader as head,” Reuters, August 2, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-oil-zhenrong/chinas-iran-speci….

[33] State Council General Office, “State Council General Office Notice on Announcing the List of Enterprises Acting as Investees of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council,” Guobanfa No. 88, 2003, http://www.gov.cn/xxgk/pub/govpublic/mrlm/200803/t20080328_32334.html.

[34] Cissy Zhou and Orange Wang, “US Blacklist Pushes Once-powerful Chinese State Oil Trader Deeper into the Shadows,” South China Morning Post, July 26, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3020227/us-blacklist….

[35] Han Wei & Yang Ge “Update: Huawei CFO Arrested for Allegedly Violating U.S. Sanctions on Iran,” Caixin, December 6, 2018, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2018-12-06/huawei-vice-chair-arrested-in-c….

[36] “2019 Electricity Industry International Cooperation Conference & China Electricity International Capacity Cooperation Enterprise Alliance Annual Conference Held Successfully,” December 6, 2018, China Electricity Council, http://www.cec.org.cn/yaowenkuaidi/2019-05-13/190978.html.

[37] “'Guidelines for International Capacity Cooperation in the Power Industry’ Published in Beijing,” China Power News Network, October 18, 2019, http://www.cpnn.com.cn/zdyw/201910/t20191018_1171299.html.

[38] Ariel Cohen “China’s Giant $400 Billion Iran Investment Complicates U.S. Options,” Forbes, September 19, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/arielcohen/2019/09/19/chinas-giant-400-bil….

[39] Tristan Kenderdine and Peiyuan Lan, “China’s Middle East Investment Policy,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 59, 1-2 (2019): 557-584. DOI: 10.1080/15387216.2019.1573516.

[40] Tristan Kenderdine, “China’s Trade Policy Shift as International Capacity Cooperation Policy Rebranded,” Russian International Affairs Council, February 25, 2020, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/columns/asian-kalei….

[41] Tristan Kenderdine “13th Five-year Plan on International Capacity Cooperation—China Exports the Project System,” Global Policy, October 17, 2017, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/17/10/2017/13th-five-year-plan….

[42] Micha’el Tanchum “Iran and the China–Russia pivot in Eurasia,” East Asia Forum, January 4, 2020, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/01/04/iran-and-the-china-russia-pivo….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.