The main streets of Manshiyat Abdel Moneim Riad, a choked grid of hastily constructed apartment blocks spreading out from a power station at Cairo’s northern edge, are organized according to a simple principle: shops and cafes on the edge, mounds of waste, animals, and rough teenagers from the narrow tributary streets in the middle. Rickshaws and trucks battle for position and skirt potholes in between. Men in search of a bit of air brush away flies at sidewalk cafes and survey the scene with contempt.

The line at two free health clinics run by the Muslim Brotherhood stretches out the door. Around the corner, at a stand by the local mosque, a recorded voice blares from a tinny loudspeaker advertising meat and butter subsidized by the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. A small crowd gathers. Even at US$3 a pound, roughly 30 percent off the price at the local butcher, meat is beyond the reach of many families here.

That the Brotherhood had been doing this sort of charity work here for years before the 2011 uprising perhaps helps explain why Manshiyat Abdel Moneim Riad turned out so strongly in support of senior Brotherhood politician Mohammed al-Beltagi in the November 2011-January 2012 parliamentary elections. Yet, if the diverse remains of campaign posters from the May 2012 presidential election now peeling off the walls of shops are any guide, Manshiyat Abdel Moneim Riad is not the “Muslim Brotherhood stronghold” Western reporters invited to attend Brotherhood rallies here have dubbed it.

The Brotherhood wins here and in similar neighborhoods across the country not because it is overwhelmingly popular, but because it has a disciplined and motivated base and because, in contrast to much newer parties, it is there. A year ago, Hosni Mubarak’s former ruling National Democratic Party was dissolved, its members licking their wounds after protesters burned their local offices across the country, its patronage networks in disarray. The fledgling secular parties cried for social justice from television studios, but did not have the funding or the roots in neighborhood alleyways to compete. A year ago, enough Egyptians, perhaps hoping the Brotherhood’s charity work in places where Mubarak’s state had been largely absent might translate into a more charitable government, were willing to give the group a chance.

But now another senior Brotherhood politician, Mohamed Morsi, is the head of state, and the state appears more absent than ever. Government services—electricity, trash collection—are slipping. Ruthless vigilantism and mob justice are replacing brutal policing. To many here, the country appears dangerously adrift, the president not up to the task. The government may be paddling furiously—traveling the world in search of trade and investment, urgently negotiating an IMF deal to unlock aid—but some politicians privately fear it is too late: the ship, they say, capsized long ago.

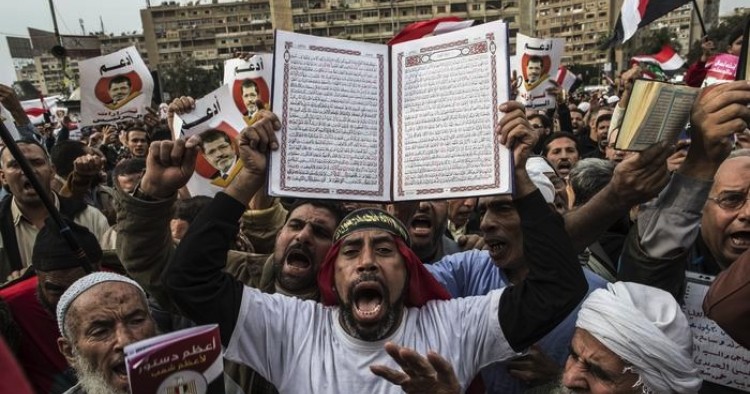

Meanwhile, the Brotherhood is still on the corner, selling discounted meat and offering free medical consultations. But such charity efforts do little to mitigate the reality that most Egyptians’ daily lives are more difficult by any measure than they were two years ago. Disillusionment and frustration with Brotherhood rule have turned to a visceral anger in many quarters, as repeated mob attacks on Brotherhood offices have showed. Protesters angry at Morsi’s November 2012 arrogation of extraordinary powers to ram through the country’s current constitution still chant “illegitimate,” as they did in 2005 protests against Mubarak’s amendments to the former constitution. But that familiar refrain has now been joined by a more damning verdict: “failure.”

The verdict, in some respects, is unfair. The Brotherhood inherited all the thorny, complex problems that contributed to the uprising, plus dire new problems the uprising created, and was left holding the bag. Whoever was so unfortunate as to be elected president of Egypt at such a time would have struggled to reverse the country’s descent in the space of a year. Others might perhaps have worked harder to pursue consensus and to share power, others might have met less resistance from the very levers of government, others might have taken more quick, even if largely symbolic, steps to court popularity. But the challenges facing Egypt were, and remain, so overwhelming that no cash-strapped government could possibly hope to meet them in a year’s time.

Yet widespread disenchantment with Brotherhood rule need not immediately translate into a Brotherhood defeat at the polls. For the moment, the opposition appears more comfortable watching the Brotherhood fail at governing than sharing the blame. Certainly, the Brotherhood has given them little incentive to do otherwise. Buoyed by their success in every national electoral contest Egypt has seen since Mubarak fell, the Brotherhood has viewed the defeated opposition’s conditions for cooperation as galling, street protests as the work of counterrevolutionary saboteurs. Many Egyptians may see the country as dangerously adrift, but the Brotherhood does appear to have set a course: to rely on its political machine, and the formal opposition’s talent for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, to deliver a new parliament that can legislate its (Islamist) agenda and to embed itself in as many state and business institutions as possible—and in the meantime to do what it can to avert an economic crisis of a scale that could upend that program.

Assembling the chaos, murky rumors, and misinformation that have marked the last two years into some sort of sense, by way of elaborate conspiracy theories or reductionist narratives, is a national pastime now growing old. Café patrons, fishmongers, and unemployed engineers still theorize that the United States is supporting the rise of “pragmatic” Brotherhood regimes in the Arab world to lay the groundwork for an Israeli-Arab peace deal, a U.S.-Israeli strike against Iran, or a pivot to Asia; that the military is preparing a coup; that Egyptian or foreign security services are fostering chaos to pave the way for a revanchist regime, either before or at the end of Morsi’s term. Sometimes, the theory goes, it is all of the above. But more seem tired of trying to make sense of the mess, more willing to posit that if there is a narrative, it is that there is no narrative: the country is descending into chaos.

Given time, Egypt will almost certainly emerge from its current troubles. When it does, it will probably not resemble any of the utopias the liberals, Islamists, leftists, farmers, and dissatisfied urban poor who stood shoulder-to-shoulder in Tahrir Square two years ago imagined. With luck, patience and perseverance, it may still emerge healthier, stronger, and more free than it was before the uprising. In the meantime, the people of Manshiyat Abdel-Moneim Riad wait patiently for free medical advice at the Brotherhood’s clinics. But all patience has a limit. The challenge for the Brotherhood, and for Egyptians in general, is to reverse the country’s downward drift before that limit is surpassed.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.