Originally posted July 2010

I am a documentary filmmaker of Iraqi origin and have lived in London for a long time. I worked for many years as a film editor on documentaries and dramas and was working toward my ultimate goal, which is to make a fiction feature film, when the first Gulf War erupted in 1991.

Like so many other Iraqis in exile, I sat glued to the TV every night, watching the “fireworks” exploding in Baghdad’s night sky and “smart” bombs taking out their targets as if in some video game. Hundreds of hours of British media coverage and yet there was not one ordinary Iraqi present in the footage; it was as if the whole country was empty, except for Saddam Husayn. For those of us with friends and family in Iraq, this created a kind of madness — a sickening realization that such coverage made it easier for ordinary people in the West to accept the war if they didn’t have to think about human beings like themselves being on the receiving end of all this firepower.

I was traumatized to the point of losing my grip on the English language, which I had spoken all my life. I struggled to remember names of the most ordinary objects — “table,” “salt,” “window” ... but maybe what was really being lost was the ability to speak about the loss. I finally rediscovered my voice, however, by making a documentary film about Iraq — a kind of history of the country from its modern beginnings in the 1920s through to the Gulf War, told through the experiences of Iraqi women living in exile in the UK. At this point I began to understand that you sometimes try to repair, in creative work, what has been shattered in the “real” world.

I went on to make other documentary films in Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, and Iran. In fact, most of my films have been about the Middle East, in one way or another.

And so I began to feel that I was like someone who lived on a bridge — between Europe and the Middle East — never entirely in one place or the other, but being a sort of conduit between the two.

My commitment is to make a space where people can tell their own stories — where they, hopefully, emerge as the complex, contradictory human beings that they are. However difficult the circumstances in which people are forced to live, I feel it is critical not to reduce them to mere abstract victims. Today, media stories about Iraq do depict Iraqis, though the narratives usually represent them as picking their way through smoke, fire, and blood in the aftermath of an explosion. Viewers are none the wiser: Who are these people? What is this neighborhood? Who is this mother crying on the pavement? Alas, all of them are portrayed simply as “victims.”

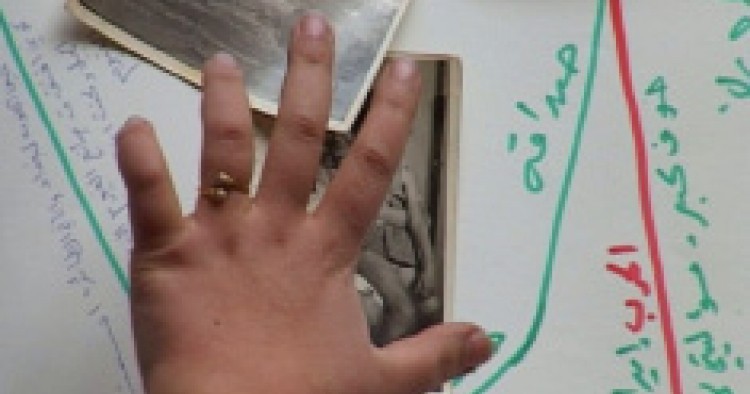

Our Feelings Took the Pictures: Open Shutters Iraq is my third film about Iraq and my most recent documentary. Its subject is an unusual photography project in which a group of women from five cities in Iraq lived and worked together for a month in a traditional courtyard house in Damascus. There they learned to take photographs, and at the same time, presented “life maps” to each other: large charts full of family photos, scrawled poetry and quotations, crisscrossing green, red, and black marker lines, detailing the ups and downs, forwards and reverses of their lives. The women unearthed memories buried for 30 years in the course of just trying to survive years of war, dictatorship, and sanctions. As I filmed the women listening spellbound to each other, without comment or judgment, I could feel them becoming more and more aware of their respective stories. It is as if the organ with which we listen to the stories of others is not our ears, but stories of our own. In the end, they had woven together the threads of their individual lives into a collective fabric of the Iraqi female experience.

Each of the women decided on the subject of the photo-story she wanted to shoot back in Iraq and returned there to take hundreds of photographs — all of them imbued with the sharp emotional truth of lived experience. Six weeks later, back in Syria, they edited their work and wrote biographies, essays, and captions to accompany the pictures. My job was to make a film about the project, although, of course, I could not help becoming deeply involved in all aspects of the work. As I watched and filmed, I realized that all of us were participating in a transformative process: taking us from exploring and articulating our largely unspoken experience to making a work of creative expression. The women’s work now forms a traveling exhibition and dual language Arabic-English book; these portray a complex lived experience and history — individual and collective.

In 2004, I returned to Iraq for the first time in 35 years. I made a film and with my colleague Kasim Abid, who also is a London-based Iraqi filmmaker. I helped to set up a free-of-charge film-training center in Baghdad. We’ve had to work in a precarious situation, starting and stopping, always being ready to improvise. Nevertheless, our students have shown remarkable commitment and have now completed 15 short documentary films, giving a sense of ordinary life in Iraq, which is largely absent from the mainstream media.

I feel that for them, as well as for the women in the Open Shutters Iraq project, and for me as a filmmaker, all our work has been a form of resistance against the “un-making” of our world — both outside and inside us. And perhaps this is the real importance of creative work in a time of war and destruction.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.