Mexico is rarely mentioned in most discussions about Qatar’s foreign policy. Likewise, the gas-rich Arabian emirate is not at the center of most analyses of Mexican foreign relations. Yet since Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani became emir in 2013, and especially since the diplomatic and economic blockade of Qatar began in mid-2017, Doha and Mexico City have begun to develop an increasingly fruitful partnership.

For years, commercial relations between the two countries were largely limited to the flow of Qatari natural gas and aluminum alloy in one direction and Mexican trucks, vehicles, and refrigerators in the other. Yet as ties have strengthened, bilateral trade has begun diversifying, and both sides are keen to expand the scale and scope of their political and economic relationship. The growth of Qatari-Mexican relations is indicative of Doha’s strategy of enhancing cooperation and investing in economies throughout the Global South, including Latin America, to secure new allies, partners, and friends. Simultaneously, as Mexico looks to expand its economic footprint in the Arab world, it sees a stronger relationship with Doha as key to achieving this.

Amid the Gulf crisis that pits Qatar against three of its fellow Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members — Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain — plus Egypt, Doha’s relations with countries such as Mexico have contributed to its ability to maintain a strong economy while continuing to expand its soft-power influence in new corners of the world. By positioning itself as an important investor in Mexico’s economy and maintaining warm diplomatic relations, Doha gave the Mexican government a stake in Qatar remaining an independent and sovereign nation amid the blockade, even though Mexico (like virtually all Latin American states) has been careful to avoid getting directly involved in the politics of the GCC crisis.

Diplomatic relations between Qatar and Mexico were officially established on June 30, 1975, but the two countries did not have much to do with each other for the next four decades. In fact, as of 2011, there were only around 250 Mexican nationals living in Qatar, and while Mexico had embassies across a score of Arab countries, it didn’t have one in Doha until 2015. Likewise, Qatar did not have an embassy in Mexico City until 2014.

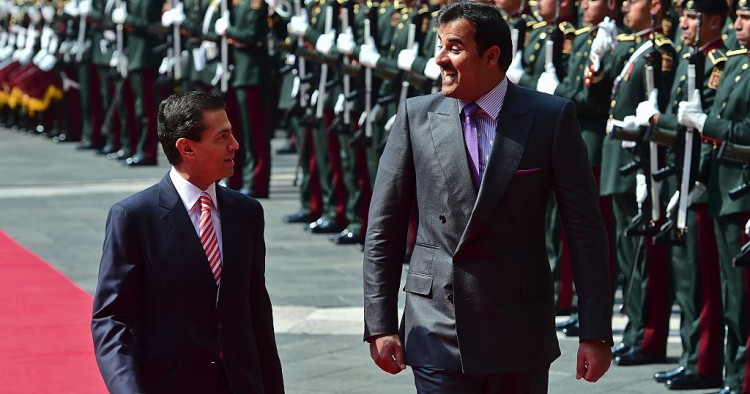

The year 2015 was a watershed for Qatari-Mexican relations. In March of that year, ProMéxico, a Mexican government investment and trade promotion agency, opened an office in Doha. Eight months later, Sheikh Tamim became the first Qatari leader to make an official visit to Mexico, where he met with the country’s then-president, Enrique Peña Nieto. During his two-day visit, which marked the 40th anniversary of the establishment of bilateral ties, officials from both countries emphasized the need to strongly denounce extremism and terrorism regardless of their origins. Qatar’s ruler also praised Mexico City for its deepening interest in the Arab world, and both sides expressed solidarity with the Palestinians’ struggle for statehood, stressing the importance of resolving the Palestinian-Israeli conflict with a two-state solution based on the 1949-1967 borders.

Beyond the symbolism, the emir’s visit led to the signing of a host of deals, including an air services agreement; a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the two countries’ main banks; a technical cooperation agreement to boost bilateral coordination in agriculture, construction, education, science, and other sectors; an MoU on youth cooperation; and an MoU between the two sides’ major business and trade councils.

Since 2015, Qatari-Mexican ties have grown closer, underscored by President Peña Nieto’s visit to Doha the following year. This was the first official visit of a Mexican president to Doha and led to the signing of numerous agreements and MoUs in the areas of culture, art, energy, education, sports, and media.

In 2017, bilateral trade stood at around $200 million. Yet the following year it witnessed double-digit growth and there is cause to be optimistic about 2019. According to Juan Cepeda, ProMéxico’s director for the Middle East, officials in Mexico City are determined to double their volume of trade with Qatar in 2019. Energy will doubtless continue to be a focus for bilateral commercial ties, underscored by Qatar Petroleum’s purchase of stakes in three offshore oil blocks in Mexico (Amoca, Mizton, and Tecoalli) from Italian energy giant Eni SpA in December 2018.

But the Mexico-Qatar bilateral relationship is about more than just energy. Other areas such as agro-food, healthcare, sports, aviation, tourism, and retail have commercial potential as well. For example, Pineda Covalin, a fashion company that promotes Mexican culture globally, opened its first outlet in the Middle East in Qatar. Mexico’s manufacturing sector could play an important role in boosting bilateral trade as well: exports of cars to Qatar fit into the picture here, as does the work of Tenaris Tamsa, a Mexican producer of steel pipes and tubes, which has plans to expand its operations in the Middle East and has already set up a representative office in Qatar.

Also significant for Qatari-Mexican economic relations was the news that Qatar Airways Cargo began freighter services to Guadalajara, a new destination on the transpacific freighter route, on Jan. 6. The route runs from Macau to Los Angeles, and then on to Mexico City and Guadalajara before returning to Qatar via the Belgium cargo hub of Liège. As Mexico’s third-largest economic center and the capital of the State of Jalisco, Guadalajara is important to the country’s global trade, and the launch of the freighter service will doubtless help as Mexico City works to deepen its commercial relations with Doha and expand bilateral trade flows.

Qatar is set to host the FIFA World Cup in 2022 and the global sporting event has been an important source of new business for Mexican firms looking to expand in the region. Dunn Lightweight Architecture, a subsidiary of Mexico’s Dunn Arquitectura Ligera, which is responsible for designing and installing roofs on stadiums in Al Rayyan and Lusail, became the first firm to secure a 2022 World Cup contract. In another deal related to the World Cup, COMSA Mexico, the Mexican subsidiary of Spain’s COMSA Corporación, will provide ambulance services during the event. Having hosted the World Cup in 1970 and 1986, Mexico has experience that will be useful to Qatar, and both countries are set to enhance coordination in the lead up to 2022.

The agro-food sector has seen a notable rise in activity as well. Food security has been a particularly important issue for Qatar since the blockade began given Doha’s previous reliance on Saudi Arabia for the vast majority of its food imports. In 2016, as part of ProMéxico’s efforts to boost bilateral trade, Qatar opened its halal beef market to imports from Guci, a Mexican firm, which began shipments to Doha 11 months after the GCC crisis broke out. Mexican avocados are now for sale in Qatar too, after Coliman, a Mexican trading company, signed a deal to supply the emirate with four containers each month.

The strengthening of Qatari-Mexican relations is part of a broader effort by Doha to make itself a valuable ally and partner to a host of countries worldwide, much to the dismay of the Arab states that have invested heavily in isolating it. Despite the blockading states’ efforts to advance their narrative — that Qatar is a pariah state — Doha’s ties with countries around the world gave their governments strong incentives to reject Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s anti-Qatar line.

Although Mexico also enjoys warm relations with the blockading states and has been keen to avoid taking sides on any of the ideological issues at the heart of the GCC dispute (in contrast to El Salvador, which quickly expressed solidarity with Doha after the blockade was implemented), there is no doubt that Mexico has helped Qatar weather the blockade.

While Doha’s links with Turkey, Iran, Oman, Kuwait, and India were of greater significance in helping the emirate deal with the impact of the blockade, Qatari-Mexican relations have taken on new importance in this “post-GCC” period and serve as an example and success story as Doha looks to deepen and broaden its links with the rest of Latin America.

RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.