The explosion at the Port of Beirut on Aug. 4 has resulted in a further escalation of the political and economic crisis in Lebanon. Its repercussions can already be deeply felt in neighboring Syria and are expected to take an even greater toll on the country given its complex links to Lebanon. This crisis is feeding into Syria through multiple channels and has severe implications for its ability to import goods and, ultimately, its food security.

The explosion at Lebanon’s principal port resulted in over 150 deaths and thousands of injuries, left hundreds of thousands of people homeless, and caused severe economic damage, with reconstruction costs estimated to be in the billions of dollars. At the time of the explosion, Lebanon was already in a state of economic disarray. The country defaulted on its debt in March and talks with the IMF have stalled, resulting in a sharp fall in the Lebanese pound on the black market and a steep rise in inflation. Coupled with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, this had already led to a deep economic contraction, which, following the blast, may reach -24 percent in 2020, according to a recent estimate.

Impact on imports

The disaster at Beirut’s port is unlikely to disrupt the overall flow of imports into Syria. Although large parts of the port have been destroyed, its container terminal has remained largely intact and operations are rapidly being restored. Moreover, restoring full capacity is not necessary at this stage, as data published by the Port of Beirut show that, prior to the explosion, the port was already operating well below capacity due to the economic crisis.

Despite the blast’s potentially limited overall effect on Syrian-Lebanese trade, grain exports to Syria will likely contract, worsening the country’s existing grain shortages. Lebanon’s grain storage capacity is considerably diminished after the destruction of its largest grain silo, which was located within the premises of the port. This will negatively impact both the legal and illegal grain supply to Syria. Because of its inability to deal directly with international traders, the Syrian government has been forced to procure most of its international grain imports via Lebanon. At the same time, the smuggling of subsidized Lebanese wheat across the border had been flourishing in the month prior to the explosion, as smugglers seized considerable arbitrage opportunities arising from price differences. Syria is heavily dependent on grain imports and is already facing severe bread shortages, according to Mike Robson, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s Syria representative. Moreover, the messages coming from officials in Russia provide little indication that one of the regime’s key allies is willing to fill the shortfall in Syrian grain supplies.

Currency depreciation and the financial sector

A further deterioration in the Lebanese economic climate in the aftermath of the explosion will have multiple ripple effects for Syria. Throughout the ongoing conflict in Syria, movements in its black-market exchange rate have been sensitive to developments in Lebanon. Since the start of the year, the black-market pound has depreciated from 915/USD to 2140/USD (as of Aug. 28, 2020), losing over 55 percent of its value. The steep decline has forced the Syrian government to repeatedly devalue the official exchange rate.

The Syrian economy is sensitive to developments in Lebanon given its extensive reliance on the Lebanese financial sector. Since the beginning of the civil war, Syrian banks have lost most of their access to the international financial markets and transaction volumes have fallen steeply. Syrian individuals and institutions have become an increasingly important group of depositors in Lebanese banks, although the total size of Syrian deposits is unclear as the Lebanese central bank, Banque du Liban (BdL), does not offer a breakdown of non-resident deposits by nationality. Estimates of the size of Syrian deposits in Lebanon vary widely, but are believed to constitute a significant share of total non-resident deposits. In a much cited report from the beginning of the year, Ali Kanaan from the University of Damascus estimated that Syrian deposits exceed $40 billion. Other estimates put them at $30-40 billion. It is also well documented that key Syrian businessmen have been using Lebanese vehicles to overcome international sanctions and access dollars on global markets.

Lebanon’s financial institutions have been increasingly locked out of international capital markets following the BdL’s imposition of capital controls and restrictions on dollar withdrawals. An immediate consequence of this has been that the flow of dollars from Lebanese banks across the border into Syria has dried up — a situation that is now only likely to intensify. Furthermore, Syrian deposits risk becoming subject to sizeable haircuts, should restructuring plans for the Lebanese financial sector go ahead as envisaged. Such a scenario is increasingly likely considering estimated losses of close to $100 billion across the sector. A shortage of dollars will keep the Syrian pound under pressure, meaning that further currency depreciation almost certainly lies in store.

The deepening Lebanese economic crisis will also weigh on remittance flows into Syria. Remittances are an important source of Syrians’ household income. Lebanon hosts around 1.5 million Syrian refugees, as well as large numbers of Syrian economic migrants. According to the latest World Bank estimate, annual bilateral remittance flows from Lebanon to Syria amount to a quarter of a billion US dollars or 16 percent of Syria’s total incoming remittance flows, making Lebanon the second largest source of remittance flows to Syria after Saudi Arabia (30 percent). A collapse in economic activity in Lebanon will continue to hit the incomes of Syrians living in the country, reducing the flow of funds repatriated back to Syria. Lower remittance flows will act as another headwind to the Syrian pound.

Import dependence

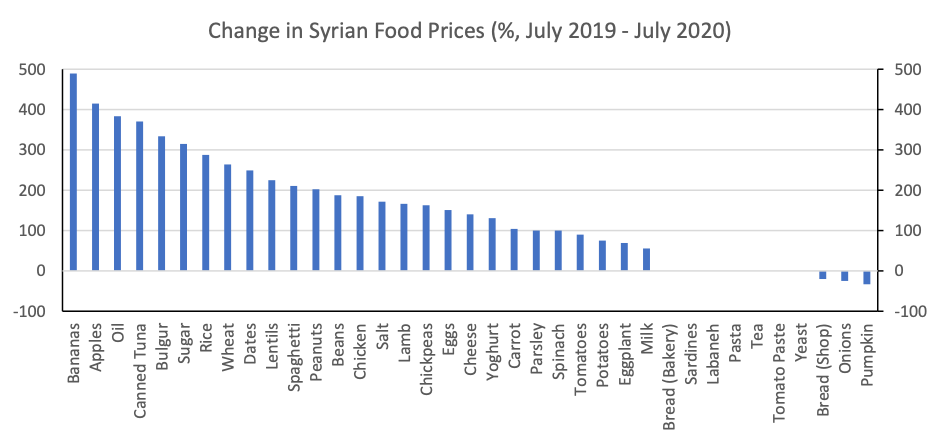

Syria is very dependent on imports. The prolonged civil war has led to a collapse in domestic industrial output and agricultural supply, making the country increasingly reliant on manufactured goods and foodstuffs produced overseas. Accordingly, currency depreciation and a reduced supply of imports will push inflation higher. The country’s import reliance means that currency falls feed quickly into higher domestic prices. There has already been a surge in the cost of food. Data from the UN World Food Program (WFP) highlight that the prices of several important foodstuffs — including oil, bulgur, wheat, and rice — have more than tripled over the past year. Prices for meats, such as chicken and lamb, have also more than doubled during this period. With further exchange rate depreciation likely, food inflation looks set to climb higher in the near term.

Inflationary pressures will lead to a further shift to alternative currencies. Their adoption is already well advanced in areas not controlled by the Syrian regime. According to a July COAR report, “In northwest and northeast Syria, respectively, Turkish lira and U.S. dollars have become sources of bedrock fiscal stability,” and it further noted that “foreign currencies have become indexes for highly important commodities, salaries, and consumer goods, while further potential exists for deep impact on a wide spectrum of matters related to commerce and local administration.”

The surge in inflation is another headwind for an economy already reeling from an escalation in the prevalence of COVID-19. Anecdotal evidence suggests that there has recently been a spike in fatalities. In light of this, the Ministry of Religious Endowments suspended Eid and Friday prayers in late July in Damascus and the surrounding area and authorities in the northeast of the country banned all large gatherings on July 23. As the virus becomes increasingly widespread, a more severe lockdown lies in store and economic activity looks set to suffer.

Protesting rising prices

Against this backdrop, protests against the regime in traditional strongholds could mount. We have already seen protests in the south-western (predominantly Druze) city of Sweida in light of the food price increases, which included calls for President Bashar al-Assad to stand down. These protests were particularly striking as the city has been under regime control throughout the war, and there had been little prior public dissension. Protests also reportedly took place near Damascus — another regime stronghold. If food inflation climbs higher, as seems likely, the protests could intensify.

At this point in time, these protests only present a small risk to the regime. The stability of Assad’s regime is still more likely to be endangered by the continued presence of jihadist groups in the north of the country — particularly Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in Idlib — and the ongoing rebellion of the Syrian Kurds as represented by the Democratic Union Party (PYD).

However, escalating protests are a risk to keep an eye on. The key threats to the Assad regime have eased following Russia’s intervention in late 2015 and the deployment of Iranian troops in April 2016, which eventually led to the regime regaining territory. A fresh risk stemming from escalating protests may be one that flies under the radar, but eventually presents a larger danger to the stability of the regime than is currently widely anticipated.

Benedikt Barthelmess is an economist who is currently teaching at Sciences Po, Paris. He is a former visiting researcher at the Cairo-based Centre d'études et de documentation économiques, juridiques et sociales (CEDEJ). Liam Carson is an economist covering the Middle East and Africa. Currently an Overseas Development Institute fellow, he was previously employed as an emerging markets economist for five years at Capital Economics. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.