Through the collaboration between Iraq and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), US providers have learned a great deal about improving behavioral health services, including trauma services, from their Iraqi colleagues since 2004.[1] Two of the many implications for US behavioral health services resulting from this partnership are directly relevant to shaping services for both returning veterans, and refugees and immigrants from the Middle East:

- Programs in the US need to increase the involvement of families and communities

- In reviewing the full range of observations detailed throughout the Monograph for the Iraqis’ first visit in 2008, one issue/lesson trumped all the others: the centrality of family and community in the lives of Iraqis, especially in such critical life events as marriage, the role of extended family, child rearing, trauma, illness, and the like. This family orientation was evident in both the visiting teams’ reactions to the services they observed and also in their projected plans for services back in Iraq. For example, one Iraqi team that came to the US to learn about community-based mental health services is implementing a model of such services for persons with serious mental illness in which a family member is hired to serve as a case manager. US host providers who participated in this program commented that the Iraqis did not want to visit nursing homes or hospices, for example, “because people in Iraq are never alone or deserted” and noted repeatedly how, in turn, they planned to develop and strengthen the family and social support components of their services to their clients.

- “Recurring or Ongoing Trauma” may be a more appropriate characterization for much of the trauma experienced in conflict regions and under other circumstances (e.g., inner city street violence, domestic violence, childhood abuse, etc).

- The phenomenon of recurring trauma has been the topic of much discussion among concerned professionals, both in the US, following redeployment of soldiers into combat zones in recent years, and also in Iraq, which has been in a state of war and turmoil for several decades. US providers were reminded by their Iraqi colleagues that, in situations of constant threat and recurring violence over a period of time, health consequences may be different from those that follow a one-time exposure. Repeated or continuing trauma may have more serious health and mental health consequences that require careful examination, particularly with regard to issues of diagnostic characterization and approaches to treatment and rehabilitation. In other words, the intensity, duration, and frequency of exposure to violence must be carefully reconsidered in conceptualizing and assessing psychopathology, and also in our approaches to treatment and rehabilitation.

Potential research questions that warrant investigation include the following:

- Are there differences in the diagnostic characterization, severity, and chronicity of behavioral health problems that follow a single or multiple exposures to various levels of violence? If so, are there any significant differences in response to various psychological and/or psychopharmacological approaches to treatment? In other words, does intensity, duration, or frequency of exposure to violence have implications for the nature or severity of the health problem that follows (e.g., headaches, somatic problems), and also for the problem’s response to one or another specific treatment?

- What are the “active ingredients” of family involvement and support that contribute to a patient’s resilience and/or recovery? During childhood and adolescence, how does the intensity and duration of family involvement and support contribute to resilience?

- Do differential levels of family involvement in the lives and treatment of patients with a given behavioral health problem (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, drug abuse, etc.) have a differential effect on the course and outcome of treatment (psychological, social, academic, development, or a combination)? If so, is it intensity, frequency, or duration of family involvement that is important?

The answer to these and similar questions concerning socio-cultural, developmental, and genetic factors and their relevance to behavioral health may have implications for health policies and practices in many countries, but clearly need to be addressed as the US struggles to address the behavioral health needs of its veterans and immigrant populations.

In addition, SAMHSA and the US providers who participated in this activity learned other significant lessons for improving services in the US:

- Understanding other cultures is the foundation for working effectively with other countries to both help them identify and address their own needs — and also to help the US providers better understand and address the needs of refugees and immigrants from those and culturally similar countries. As one participant put it, “an essential requirement for an effective helping role will require an adequate level of … understanding, trust in each other and a sense of a common purpose.”

- Iraqi notions of mental health and well-being were both inspirational and significant for working with other populations in the US who have experienced trauma:

- Religion/spirituality is essential to Iraqis in achieving and maintaining mental health and well-being. Religion/spirituality is a major factor in the lives of Iraqis and can serve as an effective therapeutic measure where well-trained spiritual leaders can play important roles in health education, prevention of illness, and compliance with medical advice. US host sites reported that the Iraqis were surprised by the lack of involvement in mental health and substance abuse services by religious leaders in the US. Although religious leaders are not viewed by Iraqi health professionals as therapeutic allies or collaborators, the average Iraqi individual and family seek comfort and peace through religious rituals and institutions when in distress or facing major problems of any kind. Religious leaders often advise patience, perseverance, hope, and trust in God.

- The Iraqis provided lessons about the impact of war and how people put conflict behind them, an example of resilience and inspiration to US hosts. The world is interested to know how wars end, how people put conflict and strife behind them and move on to a new life. It has been educational to see Iraqis look at tolerance and models of restorative justice as mental health issues in moving beyond the conflicts that have involved Iraq and the world beyond. Participants in the Iraq-SAMHSA Initiative, from both Iraq and the US, acknowledged and took seriously the impact of war (conflict) on Iraqis and Americans. The particular way in which we collectively focus on war-related issues is to understand the impact of violence, terror, or trauma and their ramifications psychologically, socially, and biologically, particularly through programs that view trauma as a component element of mental and physical disorders. Not only did the Iraqi guests demonstrate how, when in a peaceful environment that is free from ongoing conflict, they could immediately “get to work,” attend and learn, but they also regaled their hosts with funny stories and showed how, in the midst of terror and trauma, a sense of humor is invaluable.

As the Iraq-SAMHSA Initiative progressed, it became evident that the Iraqis were equipped to be true partners with their US colleagues as evidenced by their ready adoption of two major evidence-based practices used in the West:

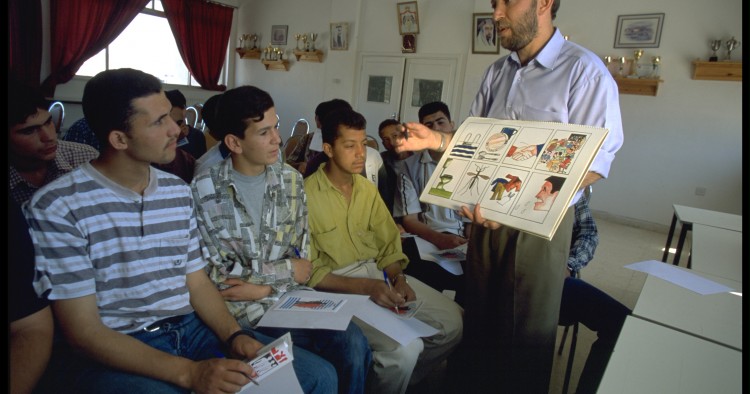

- The use of multidisciplinary approaches in meeting behavioral health needs: The concept of multidisciplinary teams in addressing behavioral health needs of clients was readily accepted by the Iraqis. This, we believe, is due to several factors including: a) the new and well-informed behavioral health leadership at the national level; b) the severe shortage of trained mental health specialists as a direct consequence of a massive “brain drain” during the past 30 years; c) the availability of few other behavioral health professionals (psychologists, social workers, nurses) in Iraq; and d) the specific requirement by SAMHSA for Iraqi teams applying to be part of the Iraq-SAMHSA Initiative to organize and implement their projects in a multidisciplinary manner. Even so, the Iraqis’ quick and sincere adoption of the Multidisciplinary Team approach underscored the critical role this approach plays in effective behavioral health services, regardless of cultural or country differences, and the Iraqis’ incorporation of this approach in all their implementation plans and activities in Iraq was both inspiring and significant.

- Integration of behavioral health services into primary care is a useful and necessary strategy in a country like Iraq that has too few mental health specialists (e.g., psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, psychiatric social workers, and psychiatric nurses) for its population. This doesn’t simply mean primary care providers prescribing psychoactive medications, but also being well trained to conduct effective interventions and to collaborate with mental health specialists in addressing the cognitive, affective, motivational, and social needs of their patients. Moreover, providing mental health services within the primary health care setting aims to deliver comprehensive/holistic care while also reducing the impact of stigma typically associated with mental hospitals and clinics. The Iraqi teams and their national leadership are demonstrating the importance of this kind of systems-planning in limited resource settings. US providers noted however, that such comprehensive planning is important in all health systems. The United States has much to learn from countries that more systematically develop national strategies and plan the integration of behavioral health services into general health services in an effort to address the health needs of their people.

Finally, as SAMHSA staff, host sites participants, and members of the Planning Group on Iraq Mental Health reviewed our shared experiences with the visiting Iraqi health professionals, all aiming to improve behavioral health services in their country, it became clear that these experiences have certain implications for US service providers that are grounded in fundamental psychobiological needs that are common to all people, such as:

The need for physical and psychological security, social connections and support; the need for a certain degree of autonomy, self reliance and competence; the need for openness and fairness when dealing with others, including governmental authorities and the need to be recognized, respected and accepted.

These common and shared needs, coupled with a general fear, stigma, and shame typically associated with mental illness and substance misuse and dependence in both countries, provided the common ground for sharing valuable observations and insights during the Iraqis’ visit to the US that helped providers from each country improve services.

[1]The authors wish to acknowledge and thank members of the Planning Council who contributed to the preparation of this essay.

1. Implications identified by members of the Planning Group on Iraq Mental Health in 2010 and published in the forthcoming monograph, Lessons Learned from the First Cohort of the Iraq-SAMHSA Initiative.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.