Carried out under the banner of defending the mostazafan (oppressed), the Iranian Revolution of 1979 aimed to restructure not only Iran’s society and political system, but also others across the Islamic world. Refusing to align with either the United States or the Soviet Union in the Cold War, the newly established Islamic Republic sought to create a new geopolitical order in the Persian Gulf and greater Middle East based on a mantra of “neither East nor West.”

Geopolitically, the Iranian Revolution did more to transform the Middle East than any other event in the second half of the 20th century. The end of 2,500 years of Persian monarchy quickly did away with Washington’s “Twin Pillars” strategy, which relied on close ties with Saudi Arabia and – even more so – Iran to marginalize Ba’athist Iraq and prevent the emergence of a pro-Moscow order in the Persian Gulf. President Richard Nixon, whose administration established the strategy, frequently called Iran, Turkey, and Israel America’s “cops on the beat” along the periphery of the oil-rich Arab states. Relations between the U.S. and Iran deteriorated dramatically after the Islamic Republic’s establishment, however, with both sides engaging in what RK Ramazani called “mutual satanization” as the 1979-1981 hostage crisis led to decades of distrust and vitriol between Washington and Tehran.

Washington quickly learned that the Twin Pillars strategy failed to account for the role of government legitimacy in maintaining regime stability. This legitimacy and stability collapsed in 1978-79 amid a popular revolution following the shah’s failure to implement necessary reforms to improve the lives of Iran’s middle class. As such, the U.S.’s previous dependence on Iran during the 1970s quickly proved to be a key weakness in its Middle East foreign policy. As a RAND Corporation report stated, “A strategy based on structures of power without regard to internal governance proved to be only as stable as its least stable pillar.”

Regional impact

The effects of the Iranian Revolution resonated throughout the Persian Gulf. The Western-allied Gulf monarchies quickly adapted their perceptions of security and their strategies for countering regional threats. In 1981, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) formed the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), with the chief goal of safeguarding their monarchies. While the decision to establish the GCC can be partially attributed to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, it was the new Iranian regime’s rhetoric and conduct that shook Arab Gulf leaders to their core. Gulf countries with significant Shi’a populations – Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia – were especially alarmed. The Arab Gulf sheikdoms soon agreed that each would fare better if they adopted unified and coordinated defense policies, rather than trying to go it alone.

Nonetheless, Riyadh was cautious in its initial response to the new revolutionary leaders in Tehran, despite finding Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s regime deeply unsettling. King Khalid of Saudi Arabia sent the secretary-general of the Organization of the Islamic Conference to congratulate the new Iranian government, and he issued a statement calling the Islamic Republic’s establishment a “precursor for further proximity and understanding” between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Notwithstanding the Saudi king’s initial overtures, relations between Riyadh and Tehran quickly soured. Outbreaks of anti-regime violence led the Saudi leadership to be more wary. First, Sunni fundamentalists seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca in late November 1979 and called for the overthrow of the House of Saud. Only two weeks later, an anti-government uprising in Saudi Arabia's Shi'a-majority Eastern Province resulted in deaths and injuries among Saudi Shi’as at the hands of state security forces. The Saudi leadership saw Iran’s hand in the unrest, as well as in the failed coup plot against Bahrain’s al-Khalifa ruling family and the various acts of terrorism and subterfuge in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia carried out by Shi’a groups throughout the 1980s.

Relations between Riyadh and Tehran grew even more strained following confrontations between Iranian pilgrims and Saudi police during several hajj pilgrimages in the 1980s, most notably in 1987, when 400 died amid such clashes. From Saudi Arabia’s perspective, such turmoil was a major threat to the religious legitimacy of the al-Saud rulers and a direct result of Khomeini’s characterization of the hajj as a “political occasion” as much as a religious one. Later, Riyadh and most other GCC capitals supported Iraq after its 1980 invasion of Iran as the two countries fought what became the longest conventional war of the 20th century, ensuring relations would remain strident for decades thereafter.

But the tensions between the Arabian Peninsula’s monarchies and Iran did not begin with the Iranian Revolution or the Iran-Iraq War. In the decade before the shah’s fall, Gulf monarchies grew increasingly unsettled by what they perceived as Iran’s efforts to establish Persian hegemony in the region. This was fueled by Tehran’s seizure of three Emirati islands in 1971, as well as its sovereign claims to Bahrain. Ayatollah Khomeini’s rise, however, did add a new dimension: Iran went from being simply a strategic threat to an ideological and religious one – a hostile state fully committed to wreaking havoc in Arab societies.

Today the view that Iran’s regime poses a grave threat is common among many officials in the GCC, especially in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Manama. They continue to see Tehran as the main source of regional instability. In 2010, the UAE’s ambassador to Washington, Yousef al-Otaiba, stated that “out of every country in the region, the UAE is most vulnerable to Iran. Our military … wake up, dream, breathe, eat, sleep the Iranian threat.” From this perspective, all Arab states should be interested in collective efforts to counter Iran’s growing influence across the Arab world, exemplified by its support for the Assad regime in Syria, the Houthi rebels in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and countless Shi’a militias in Iraq.

Intra-GCC divisions

Nevertheless, even 40 years after the revolution, the GCC remains divided on the most important issues in Arab-Iranian relations. Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar — half of its members — have essentially accepted Iran’s leadership and role as a rational player in the region. Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE’s decisionmakers in Abu Dhabi, however, view the Islamic Republic as a hostile actor that must be confronted aggressively.

Furthermore, changes in the Arabian Peninsula’s geopolitical order and intra-GCC tensions have further undermined the bloc’s goal of “Arabian Gulf unity” against Iran. Iran’s relatively warm and cooperative ties with Qatar have been both a cause and effect of the GCC dispute and the diplomatic and economic blockade of Qatar that began in mid-2017.

The so-called Anti-Terror Quartet (ATQ), which comprises Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, issued 13 demands for Qatar that would serve as a basis for reconciliation. The first demand addressed Iranian-Qatari ties, which the ATQ sees as threatening GCC security, and insisted that Doha scale back diplomatic relations with Tehran, close the Iranian mission in Qatar, expel Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps members, end military and intelligence cooperation, and comply with US and international sanctions on trade.

Yet as a result of the blockade, Qatar was essentially forced to deepen its relations with Iran. It turned to its Persian neighbor to ease the impact of the blockade and avoid capitulating to the ATQ’s demands, which would have, in effect, cost Qatar its sovereignty. That Doha restored full diplomatic ties with Iran shortly after the crisis erupted — a year and a half after it withdrew its ambassador to express solidarity with Riyadh in the Iranian-Saudi crisis that followed the execution of prominent Saudi Shi’a cleric Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr in 2016 — highlighted the emirate’s pragmatic approach to dealing with the new realities created by the blockade. Put simply, the Qataris understood that working with Iran on a pragmatic basis to address their vital strategic objectives was their only option, notwithstanding issues that had previously been a major source of friction, such as the Syrian war. From Iran’s vantage point, the Qatar crisis and Tehran’s deepening relationship with Doha present invaluable opportunities to exploit intra-GCC divisions.

Oman has long maintained the best relationship with Iran among the GCC members. The sultanate’s proximity to Tehran is rooted in Muscat’s neutrality and diplomatic efforts during the Iran-Iraq war, as well as the close bonds between Iranians and Omanis that developed during the shah’s era when Tehran aided Sultan Qaboos in his fight against Marxist rebels in Dhofar. Oman also shares the strategic Strait of Hormuz with Iran, and it has long pursued an independent relationship with the Islamic Republic that has, at times, irked the leadership in Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.

This special relationship is illustrated by Muscat’s role in hosting secret talks between American and Iranian diplomats in the lead up to the signing of the Iran nuclear deal. Oman has aimed to serve as a diplomatic bridge between Iran and other GCC members, as well as their Western allies. Despite these aims, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi remain frustrated by Muscat’s alleged tendency to discount Saudi and Emirati concerns when engaging Iran.

Oman, Kuwait, and Qatar’s refusal to celebrate the Trump administration’s withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal highlights the GCC’s deep divisions with respect to Tehran. It is clear that the council lacks the ability to collectively push back against Tehran’s conduct in both Yemen and the Levant given its members’ divergent threat perceptions of the Islamic Republic.

In light of Iran’s ascendancy, the GCC’s internal disputes, and Washington’s declining influence in the region, Muscat and Doha view their interests as best served by counter-balancing Riyadh and Tehran, rather than aligning with the Saudis. Put simply, at this point, the Qataris and Omanis view some of their fellow GCC members as graver threats than Tehran. Oman’s interests in deepening cooperation with Iran in the gas sector further disincentivizes Muscat from supporting anti-Iranian actions backed by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. Oman was absent from a meeting at the end of January in which diplomats from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, and Kuwait addressed Iran and Turkey’s activities in Syria. This absence further underscores Muscat’s disinterest in regional initiatives against the Islamic Republic or Turkey.

As Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the Trump administration press more Arab states to adopt anti-Iranian stances, the smaller GCC members must make careful decisions about their ties with Iran. The Qatar blockade is illustrative of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s maximalist policies aimed at countering the influence of Iran, as well as Turkey, in the Gulf’s political landscape and security architecture, which have left both Kuwait and Oman fearful that one day they may get the “Qatar treatment” from Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

Consequently, the littoral states of the western Gulf will find themselves under greater pressure and face the grave risk of a direct military confrontation between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Such a doomsday scenario cannot be dismissed. Although Tehran and Riyadh likely view an Iranian-Saudi war as too costly and dangerous to consider, the risk of such a conflict erupting looms larger today than at any point since the Iranian Revolution 40 years ago.

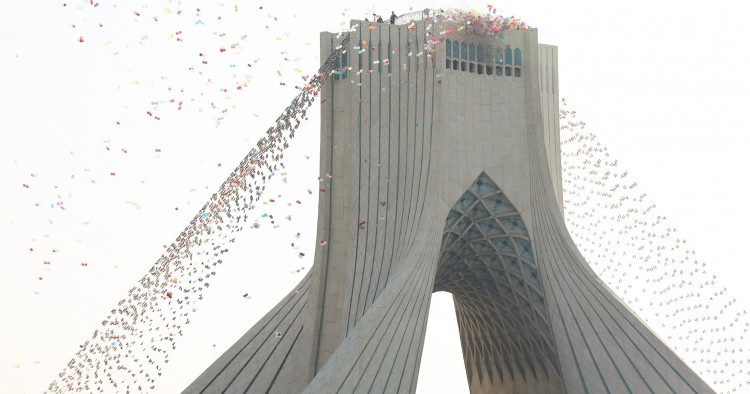

Photo by Fatemah Bahrami/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.