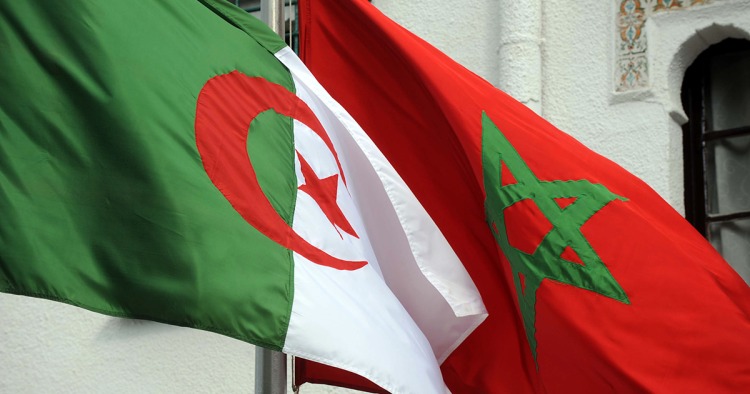

The rivalry pitting Rabat against Algiers has been intensifying for years. But there are increasing risks that the political and economic competition between the two North African neighbors will accelerate into new and more challenging directions.

The main issue underlying the dispute is not new. Morocco has long claimed that the Western Sahara, a resource-rich former Spanish colony in West Africa, is part of its own territory. Rabat has made securing international recognition for its sovereignty over the territory its main diplomatic objective. Algeria, by contrast, has continued to support the Polisario Front, which has fought for the independence of what it calls the Sahrawi Arab Republic since the early 1970s.

The growing dangers arise from a confluence of factors. First, the military buildup from both sides has continued to ratchet up tensions. Second, Algeria’s growing diplomatic assertiveness will increase its voice in international affairs. Third, on the ground, Morocco’s willingness to use drone strikes to eliminate members of the Polisario Front has the potential to precipitate an escalation.

Conflict continues to degrade the broader relationship

While the disagreement is centered around the issue of how to resolve a territorial dispute — one which is key to Morocco’s idea of itself but also partly to the legitimacy of its monarchy — it has poisoned relations between the two countries in most other areas.

Over the years, the scope of the disagreement has expanded, reducing bilateral cooperation. After a skirmish with Moroccan forces at the Guerguerat border crossing — which connects Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara with Mauritania and is regularly used to transport the kingdom’s exports into Western Africa — in November 2020, the Polisario Front unilaterally ended an ceasefire agreement overseen by the United Nations that had held for nearly 30 years. Since then, Moroccan forces and Polisario fighters have regularly exchanged artillery fire.

Later, after blaming Morocco for instigating wildfires in the Berber-majority Kabylie region and supporting separatist sentiment there, Algeria announced in August 2021 a complete severing of diplomatic ties with Morocco.

Energy cooperation was next. After months of ambiguity on the matter, by October 2021, Algeria opted not to renew the contract for the Maghreb-Europe gas pipeline, which was used to supply Algerian natural gas to Spain through Morocco, providing the kingdom with 65% of its natural gas consumption. Algeria’s decision to halt gas supplies to Rabat was a clear escalation of tensions, and one that forced Morocco to quickly adapt its energy import system.

Tensions reignited when three Algerians were killed in an attack in the Polisario-controlled part of the Western Sahara in November 2021, driving on a road that connects Algeria to Mauritania. With images of burnt-out trucks seemingly suggesting a bombing attack, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune called it a military strike carried out by Morocco with “sophisticated equipment” and vowed to respond. The mention of “sophisticated equipment” seemed to be a direct reference to Morocco’s increased use of drones to maintain military superiority in the disputed territory.

What to expect from a more confident Algeria

Over the coming months, a more active Algeria will create new challenges for Morocco. For years, the Algerian regime was hampered by weaknesses at home and had limited influence abroad. But recently, Algiers has seen its internal and external positions improve. After enduring a wave of nationwide popular protests in 2019-21, the military-led autocratic regime was able to curb dissent, using repression and by taking advantage of COVID-19 restrictions.

Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine further enhanced regime stability, pushing up energy prices and transforming Algeria into a critical partner for European countries looking to reduce their reliance on Moscow’s hydrocarbon supplies. Higher energy revenues have helped the Algerian authorities to placate domestic discontent through greater social spending, and they have also increased Algeria’s diplomatic and strategic importance.

Diplomatic showdown

Algeria’s greater regional weight will be further enhanced in 2024-25, as the country takes a temporary seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). This will likely give it new mechanisms and clout to try to reposition the discussion over the status of the Western Sahara on the mainstream diplomatic agenda.

The U.N. still considers the Western Sahara to be a non-self-governing territory. It has advocated for a political settlement to the conflict, through the possibility of self-determination. Initially this was to be achieved via a referendum. But a vote that was set to take place in the early 1990s never materialized, largely because of disagreements over who would be eligible to participate. For the Polisario Front, only the territory’s initial inhabitants should qualify to vote. But Rabat has argued that Moroccans who were part of the government’s migration schemes to encourage relocation to the Western Sahara from the 1970s onward should also have a say as well. Since then, the U.N.’s political process has stalled.

The paralysis has allowed the Moroccan authorities to increase their control on the ground and gain additional international support. Rabat calls the territory its “southern provinces” and has since proposed it be administered as part of the kingdom and benefit from autonomy within Moroccan borders and political authority.

In late September, Algerian and Moroccan representatives at the U.N. exchanged heated words on the issue. Algerian Ambassador Amar Bendjama asked, "If the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara had really turned it into a paradise, with or without the granting of autonomy, why is this referendum being prevented?" In response, the Moroccan ambassador, Omar Hilale, said that Morocco would remain in the territory “until the end of time.” Amid ongoing heightened tensions between the two sides, similar exchanges at the U.N. can be expected moving forward.

Using diplomacy and its growing economic clout in sub-Saharan Africa, Rabat has been able to garner support for its sovereignty ambitions. Over 20 countries, essentially from Africa and the Middle East, have established consulates in the Moroccan-controlled part of the disputed territory in recent years. A huge boost was also given by the Trump administration’s recognition of Moroccan sovereignty in late 2020, in exchange for Rabat re-establishing official diplomatic ties with Israel, under the Abraham Accords framework. In Morocco’s view, this was expected to attract backing from other powerful countries, especially in Europe. But new support for a complete absorption of the Western Sahara seems to have cooled off. Fearful of disrupting economic and security relations with Morocco, European leaders often make vague and non-committal statements on the issue that can be seen to back either side of the conflict.

At the UNSC next year, Algeria hopes to bring the issue of the Western Sahara back to the U.N. agenda. Algiers also wants to push for a larger reform of the Security Council to increase the clout of African states in the body, as well as of the Global South more broadly. This will allow it to strengthen alliances and to more easily attract other countries to buy into its vision for a political settlement for the Western Sahara through self-determination.

It will be difficult for Algeria to upend the status quo that Morocco has established on the ground. But merely making an attempt to do so will increase the friction between the two neighbors. At every turn, Algeria will attempt to counter Morocco’s strategy of expanding de facto control in Western Sahara, delaying a political resolution, as it builds international support for its sovereignty claims.

Military build-up to continue

As Morocco and Algeria disagree more vocally on the international stage, both sides will continue to back up their diplomatic talk by projecting strength. In 2022, the two countries accounted for 74% of all military spending in North Africa, with Algeria allocating $9.1 billion to its armed forces, and Morocco spending $5 billion, according to figures from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). While Algeria has kept fairly constant levels of spending, Morocco’s military expenditure has doubled since 2005.

For Morocco, weapons acquisitions have increasingly focused on surveillance and attack drones from Turkey and Israel. These seem to be playing a growing role on the battlefield as well. On Sept. 1, Morocco’s air force reportedly launched a drone strike that killed four Sahrawi fighters, including Abba Ali Hamudi, commander of the sixth military region. The strike followed fighting between Moroccan forces and the Polisario Front in the region of Mahbes. Addah al-Bendir, another Polisario commander, was reportedly killed by a drone strike in Tifariti, in April 2021. Moroccan authorities rarely comment on military operations in the territory.

Tensions flared again on Oct. 28, when there were multiple explosions in the Morocco-controlled town of Smara, in Western Sahara. The explosions, reportedly the result of an artillery attack by Polisario forces, killed one person and injured three others.

The likelihood that the kingdom will use its drones to erode the Polisario Front’s fighting capabilities is increasing. Morocco might be tempted to try to influence the situation on the ground ahead of what is expected to be a stronger diplomatic campaign by Algeria over the status of the Western Sahara.

Outlook

All of this points to increased dangers. The possibility of an open conflict pitting the two neighbors against one another is remote. Neither Algiers nor Rabat would benefit much from a war. Beyond the necessary resources it would entail, confrontation would weaken each regime’s standing with its own people.

There will continue to be regular provocations, however. Most will range between harmless heated debates at international forums and expensive military exercises along the shared border as a show of force. But escalation will be unavoidable if any further incidents lead to deaths on either side.

Although Algeria will attempt to sway diplomatic opinion in favor of a U.N.-supported solution for the conflict, it seems unlikely that Morocco can be convinced to budge on the current status quo. Rabat enjoys military and political control over the majority of the territory and has secured a degree of international diplomatic support. Algeria will have few mechanisms to erode those advantages for the foreseeable future.

It is in the Western Sahara itself that fighting will most likely escalate. Regional tensions will continue to ratchet up, feeding skirmishes between Moroccan forces and the Polisario Front in the territory. Besides the loss of life and damaged infrastructure, the revival of armed conflict will further delay a sustainable solution to the disputed territory’s future.

Francisco Serrano is a journalist, writer, and analyst. His work focuses on North Africa, the broader Middle East, and Latin America.

Photo by FAROUK BATICHE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.