Seldom has an expression in Syria generated as much irony as “ya mukhalef ya Makhlouf,” meaning you are either a Makhlouf or working illegally. While the phrase has been accurate for the past 20 years, the tables have turned and now it is Makhlouf who is the mukhalef.

Rami Makhlouf, the godfather of a financial empire estimated to have controlled a staggering 60 percent of Syria’s pre-war economy, is out of favor, out of access, and seemingly at the point of no return. Yet despite his fall from grace, he remains a powerful figure.

Makhlouf is more than just a mere name, he is a shadow ruler of the country’s black markets, a key financial pillar of its flailing economy, and has been under immense pressure from a government crackdown on corruption — augmented by the sharpened knives of his domestic enemies — for almost a year.

After a Spanish inquisition-style investigation by the Syrian Ministry of Communications into his prized asset, the mobile network provider SyriaTel, and its accounts from 2015-19, Makhlouf was becoming an isolated man. But things took a dramatic turn this past week as the 50-year-old businessman went public with his side of the story in a series of videos posted on Facebook, addressing the many questions and rumors surrounding him and his companies’ fate.

Makhlouf has appeared in two videos so far, calling out the upper echelons of Syria’s political establishment, of which he had been an integral part for over two decades. As the situation drags on and the crackdown on him increases, it is expected that he will continue appearing in order to defend himself. By making his feud public Makhlouf has created an unprecedented rift within loyalist ranks, transforming his dispute with Syria’s ruling elite from one that was tightly controlled and behind closed doors to an out in the open, nationwide row the likes of which haven’t been seen since Hafez al-Assad’s standoff with his brother Rifaat in 1984.

Makhlouf’s videos are a direct threat to Assad’s authority

As the words “To the president I say, I will not embarrass you, I will not burden you, just like 2011” reverberated around the internet, stunned Syrians watched as Makhlouf committed the cardinal sin of airing the elite’s dirty laundry in public. The billionaire magnate appeared in a 15-minute Facebook video on April 30 suspiciously titled “Be with god and do not care,” which detailed a wide range of grievances and concerns regarding multiple tax investigations into his companies.

Stressed out and sitting on the floor of his villa — thought to be in Syria — Makhlouf seemed to be quickly running out of options. His words came off like veiled threats: "If we continue down this path, the situation in the country will become very difficult.” This was a clear message that he will not back down. The first video was straight to the point; it was a last-gasp effort to win a reprieve from the taxes and provoke an intervention by Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad.

Makhlouf claimed that SyriaTel has 11 million users, pays approximately SYP12 billion in tariffs, and gives away at least half of its overall profits to the state. He has been asked to pay back an estimated SYP130 billion — a sum that would, according to him, “collapse the company.” Ayman Aldassouky, a researcher at the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, argues that the first video had several aims. “I think he sent many messages. He tries to reach a deal with Assad by reaching a mechanism to pay the money and save his companies and his assets. He tries to make Assad … part of the ongoing dispute and increase public pressure on the Syrian leader.”

The second video, defiantly titled “It is our duty to deliver victory to the believers,” was clearly an escalation and another desperate attempt to leverage whatever “goodwill” his corruption money has bought in Syria. The sharper tone was proof that things didn’t go as planned after the first video. Indeed, private sources at SyriaTel confirmed to me that three manager-level employees were arrested after it was released. Makhlouf noted his intention not to pay the fines, possibly seeing the arrests as a further ploy to sideline him.

Makhlouf is not backing down and his anger was on clear display in the second video: "This has reached disgusting and dangerous levels of unfairness and an attack on private properties, so please all of you who are watching, please forgive me. I cannot give up what isn't mine, this is god testing me,” he continued. "This is unfair, the state is using power and force in ways it shouldn't." This is a direct message to Assad that seeks to undermine the Syrian leader on a popular level. The tycoon is trying to shake up Assad’s loyalist base of support. Makhlouf mumbled, "Power wasn’t given to force people into making concessions, it was given to help people who are needy."

It seems the precious access Makhlouf enjoyed for years is now gone. Tom Rollins, a journalist covering Syria, echoes this point: “One question that arises here is: does Makhlouf even have a direct line to Bashar al-Assad anymore? This video seems to suggest that is no longer the case. And while this video effectively has two audiences — it attempts to appeal to Bashar, and to Syrians — I’m not sure it has the desired effect that Makhlouf appears to have been going for.”

Rarely does anyone, let alone an individual of Makhlouf’s standing, direct criticism at the feared intelligence agencies in Syria. Makhlouf was playing with fire when he said, “I want to direct my message towards the president. The intelligence services have begun to encroach on our people’s freedoms. These are your people, they are your supporters, and you cannot let others attack them.” Aron Lund, a fellow at The Century Foundation, elaborated: “Makhlouf isn't helping himself much with these out-of-touch, Marie Antoinette-like statements. There’s no one in Syria who believes he made his fortune through fair, honest commerce.” After Makhlouf’s appearances, his sons deleted all pictures of their extravagant lifestyle from Instagram, including any pictures of the Syrian president.

A crackdown is now well underway, with reports of arrests and security forces storming Makhlouf’s villa in Yafour in addition to a heightened security presence in Latakia, where Makhlouf has many loyalists. The number of SyriaTel employees arrested now reportedly stands at 28. Assad’s immediate response was clear, if indirect: A statement issued by the Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority confirmed that SyriaTel would be required to give a final answer by May 5 that it would accept to negotiate a payment mechanism for SYP233.8 billion, a brutal sign that Makhlouf would be forced to cough up the cash and stay quiet.

Competing telecommunications company MTN — which was also hit with a similar fine — was quick to take action and deprive Makhlouf of a potential partner to protest judicial inequality. Its main investor, TeleInvest Company, rapidly informed the Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority of its willingness to pay its taxes in accordance with the demands, with a schedule to be discussed further.

Stand-off has created a public opinion storm in Syria

The reaction within government-held areas was swift and heated. While there was no direct response from Assad or his inner circle, their non-state social-media apparatus was in full flow and effectively served as a barometer of how Makhlouf is viewed by government hardliners. Akram Omran, a staunchly pro-government journalist and editor of the social media group “Syria: corruption in the time of reform,” wrote a pointed response, the main line of which was “To Mr. Rami: Abide by the orders of the government, because no one will stand by you against their state.”

Meanwhile, the unofficial “Maher al-Assad” Facebook page hinted that Makhlouf’s video was an attempt to scare the president and wouldn’t work, quoting one of Assad’s sayings: “They want us to be afraid, and that will not happen." Reaction to the feud has generally has been mixed, with different viewpoints and factors taking center stage. A popular Latakia news network defended Makhlouf: “He provides salaries for the children of martyrs, [and] offers monthly food baskets to poor families. He has offered much and is better than 99 percent of the merchants and officials in this country.” Syrian journalist Mazen Moustafa stated, “If we had a state of law, the attorney general would have summoned Rami Makhlouf, who is present with all the documents he talked about, to show the truth and present it to public opinion. If only we had a state of law.” He added, “Rami Makhlouf feels that he is at risk of assassination, so he just wanted to protect himself.”

Firas al-Assad, the president’s cousin, was vocal in his opinion that “We all know who controls SyriaTel now,” referring to Assad’s increasing grip on some of the tycoons. Although the case against Makhlouf may be damning, the methods used by the financial authorities have been excessive, according to Syrian reporter Ola al-Bakeer, who argued, “You can see what happened to him as unjust or wrong, but he was asked for frightening sums and given a specific deadline to pay knowing that the tax collection procedures were widely reactivated almost two years ago. The amounts do not fit in any way with the size of the revenue of the company.”

A high-pressure crackdown

Carefully planned efforts to pressure Makhlouf using different organs of Syria’s financial authorities began in December 2019 when the General Directorate of Customs seized some of his assets and issued hefty fines amounting to SYP11 billion for importing products, including oil and gas, without paying tax. Abar Petroleum, Makhlouf’s Beirut-based gas and oil shipping company, bore the brunt of the fines.

The Syrian presidency was also beginning to take more direct control of the al-Bustan Organization — a hybrid entity under Makhlouf’s control with both a 20,000-man-strong paramilitary force and a well-funded charity serving thousands — and this set in motion a worrying trend of confiscations that no doubt irked Makhlouf. According to the pro-government Lebanese newspaper al-Akhbar, “The association came under the supervision of the Palace.”

With pressure starting to rise, the inner circle’s assault continued on multiple fronts. In mid-April the Egyptian authorities announced the capture of a four-ton shipment of hashish hidden in dairy and milk products from the Syrian-based company Milkman, a firm owned by none other than Makhlouf himself.

Although the beleaguered tycoon denied responsibility in a strongly-worded statement shortly after the seizure, alarms had clearly been raised regarding the activities of his business network. Makhlouf retorted when proclaiming his innocence, “Whoever distorts this company’s work, by emptying these products and filling them with narcotic substances, is a cowardly man,” but the damage was done and Makhlouf started to look like a man with a target on his back.

Assad’s coup de grace to Makhlouf’s empire was a detailed investigation by Syria’s Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority, which essentially forced the country’s two major telecommunications companies, SyriaTel and MTN, to pay SYP233.8 billion in unpaid fines and back taxes by May 5, with a stern warning that there would be consequences if payment was not made. This led Makhlouf to take drastic action as he was seemingly unable to reach the president to discuss a reprieve.

Assad was facing a growing headache and with the U.S. Caesar Act sanctions looming and Syria’s economy in dire straits, he couldn’t afford to let Makhlouf continue his financial domination. With COVID-19 forcing an unwelcomed lockdown in Syria, the daily economic loss due to halted services and trade was estimated at SYP33.3 billion, according to Dr. Ali Kanaan, head of the economics faculty at Damascus University.

Criticism has also been emanating from Russia, where murmurs of discontent with Syria’s economic problems and rampant corruption have increased. Aleksandr Aksenenok, a senior Russian diplomat, wrote that “Damascus is not particularly interested in displaying a far-sighted and flexible approach continuing to look to a military solution with the support of its allies and unconditional financial and economic aid like during the old days of the Soviet-U.S. confrontation in the Middle East.” The pressure is on for President Assad as he faces challenging times both economically and domestically, yet the plan to go after Makhlouf is unlikely to have originated in Moscow, as the potential results — greater confrontation and an adverse impact on what remains of Syria’s economy — would not be to Russia’s benefit. The Russians have always preferred not to meddle in sensitive domestic issues, especially as Makhlouf retains significant support in coastal areas where Russian bases are located.

What was the role of First Lady Asma al-Assad?

Many of the latest anti-Makhlouf policies have been attributed to Asma al-Assad, and while the first lady may have helped engineer the palace’s takeover of Makhlouf’s charitable organizations and ensure their continued operation, it is unlikely that she would be the driving force behind the effort.

Although the Syria Trust for Development — a humanitarian organization she heads — was a major competitor for Makhlouf’s humanitarian activities, the Syria Trust has resources and clout far exceeding that of the al-Bustan Organization, so its assimilation into the Syrian Trust network would only be a limited achievement.

According to Tom Rollins, “There are various rumors and theories about why this is happening. Some observers believe that Syria's first lady, Asma al-Assad, is leading this campaign against Makhlouf; others say that this supposed ‘anti-corruption’ drive was carried out at the behest of Russia. Either way, one thing that's abundantly clear is that Makhlouf appears to be in serious trouble.”

However, Makhlouf’s supporters have wasted no time in pinning the blame on the first lady. Dr. Sameeh al-Roubh, Makhlouf’s cousin, posted a now-deleted rant on social media directed at the Syrian leader: “We elected you and we have presented tens of thousands of martyrs and wounded for you to remain in power.” He goes on to call the first lady’s family “neo-Ottomans” in a less-than-subtle sectarian reference to their Sunni identity.

Makhlouf’s enemies extend well beyond the first lady though. He was known to have had a confrontation with Maher al-Assad, the president’s brother, over his close ties with the Iranians and their support and training for al-Bustan’s militias, which have served as a semi-autonomous auxiliary fighting force during the war.

According to Washington-based political analyst Ruwan al-Rejoleh, there are a number of factors behind this crisis, rather than just one linked to a particular person. “It’s unlikely that the rift is because of a family dispute, but rather an exit strategy to lift the pressure on many fronts,” adding that “[Makhlouf] probably was a competitor because Bustan is not part of the Syrian Trust Fund umbrella that is headed by the first lady.”

Despite the personal differences involved, President Assad still has the final say, and the decision to isolate Makhlouf and cut him off for now is a well thought out one. Firas al-Assad, Rifaat al-Assad’s son and the Syrian president’s cousin, viewed the struggle as not primarily about the inner circle so much as the president directly. “Rami Makhlouf knows perfectly well that his problem is not with the first lady but with the president himself,” he wrote on social media.

Was Makhlouf becoming too powerful?

Trouble has been brewing for Makhlouf since 2018, effectively starting the moment when the fighting around Damascus and other provinces ended. The wealthy financier had amassed an army, a vast fortune estimated at $5 billion pre-2011, media clout, and a large network of intricate business and military connections built up over a short period of time, making him both a looming threat and a profitable target.

During the hard-fought years of the war, Assad was overly reliant on Makhlouf’s financial power and organizations either to serve as auxiliary forces for the army or to play a humanitarian role when the regime was at its weakest. Al-Bustan was Makhlouf’s get-out-of-jail card with Syrians and he pinned his hopes on popular support coming from those who had benefited from its humanitarian assistance, which has ranged from paying for life-saving operations to providing salaries for the families of the fallen. Given its wide-ranging role, the best time to take on Makhlouf would be when the military threat to the survival of the ruling elite and the country was over.

Makhlouf was becoming a dangerous player with too much influence and power, which had grown uncontrollably during the war. Damascus was unwilling or unable to clip his wings as long as the military conflict was still raging on in strategic areas. When I spoke to Ali al-Ek, commander of the “Jeblawi paramilitary forces” in Homs, a branch of the al-Bustan Organization, in 2017, he revealed that in Homs Province alone, they had close to 5,000 fighters on paper and had been actively deploying between 3,000 and 3,500 at peak times. With power like that, it’s easy to see why a move against Makhlouf would become inevitable.

Although Makhlouf may have had legitimate grievances with the systematic attempts to undermine him, his image and that of his children has been a cause for some consternation in Syria. As many suffer from the daily struggle to get by amid sky-rocketing living costs, poverty, inflation, and unemployment, his sons were on Instagram living the high life in Dubai, showing off their massive wealth, sports cars, and private jets.

Aron Lund, a fellow at The Century Foundation, elaborated on this point: “Several times in the past couple of years Makhlouf’s adult children have caused a stir by flaunting their ultra-lavish lifestyles, splashing Ferraris and private jets and Dubai mansions all over Instagram. Most Syrian men their age have been in the army for years, living miserably and putting their lives on the line to save the government.” This created resentment among Syrians and tarnished Makhlouf’s image, which Assad’s inner circle viewed as unwarranted behavior at a time when internal dissent and anger at the quality of life in Syria was rising in loyalist areas. Lund continued, “Assad doesn’t stand or fall with popular opinion, but there might be a point where he needs to show who’s in charge. And perhaps that point has been reached.”

What comes next?

With Makhlouf’s position now under threat, there is no shortage of people who could fill the gap were his empire to be seized. The presidency would seemingly complete its takeover of the humanitarian side of his operations, while new figures like the shadowy magnate Tareq “Abo-Ali” Kheder or more established ones like Mohammed Hamsho and Samer Foz would doubtless be ready to pounce and expand their influence at Makhlouf’s expense in sectors like telecoms, media, and real estate.

Makhlouf still retains significant support within government-held Syria. He has a range of companies that have provided employment for tens of thousands of Syrians and that has bred loyalty. Through certain humanitarian ventures he has managed to cultivate a strong and sympathetic following within poorer parts of the country as well, especially in the coastal regions. Herein lies Assad’s biggest conundrum: Ruthlessly taking out Makhlouf risks losing the support of his followers, and if things don’t go to plan, it could further destabilize the country.

Another challenge for Assad is that if Makhlouf goes down with a fight, it could further tear the fabric of Syrian society. Even arresting Makhlouf — if he’s still in Syria — wouldn’t solve the problem either because he will remain a symbol of someone who could defend himself and stand up against the Syrian president. And if he were harmed or killed in the process, Makhlouf might become a martyr figure and this could create rifts that are beyond repair. All this comes at a time when 80 percent of Syrians live under the poverty line and the COVID-19 pandemic is grinding the economy to a halt. In short, the stakes are dangerously high for a no-holds-barred power struggle among the regime’s inner circle.

Danny Makki is a journalist covering the Syrian conflict. He has an M.A. in Middle East politics from SOAS University, and specializes in Syrian relations with Russia and Iran. The views expressed in this article are his own.

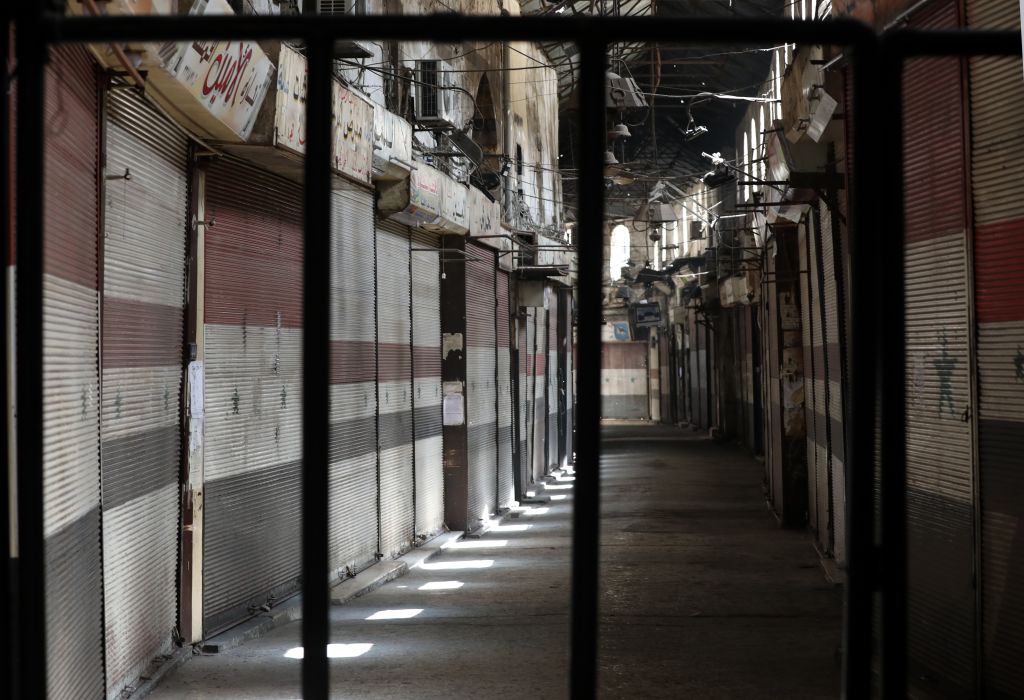

Photo from screenshot.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.