This article is part of the publication Thinking MENA Futures, produced in conjunction with MEI's Strategic Foresight Initiative and the MEI Futures Forum. Read the other articles in the series here.

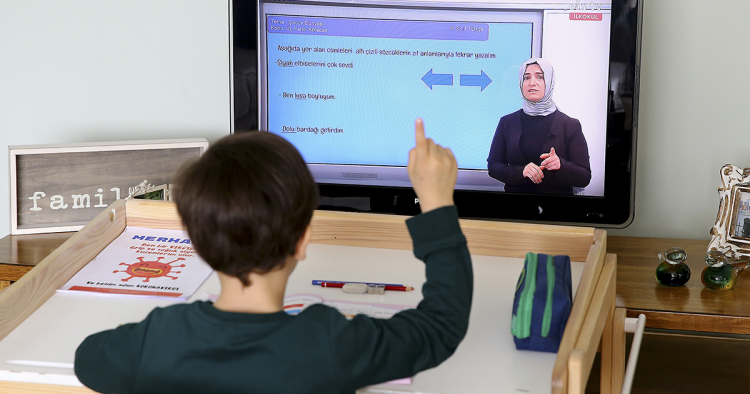

The internet is reshaping the way we learn. Before the COVID-19 crisis, the idea of online learning was already in the air and taking hold fast. The last decade has seen the rise of Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs), the creation of online marketplaces for education, and new alternatives to college like coding bootcamps. But the pandemic rocked the foundations of the learning industry and the next 10 years promise to deliver a revolution in education.

What lies ahead for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is the opportunity to rise to the frontier of the digital economy. This leap forward will require a concerted effort to make long-needed changes to educational systems, create a friendlier environment for new businesses, particularly in education technology (EdTech), and invest heavily in large-scale broadband internet infrastructure.

The current state of education in the region is a dismal sign that learning systems are failing, making the path forward difficult. According to UNICEF, before the pandemic one in every five children was not in school. The closing of schools as a result of COVID-19 safety precautions worsened the situation, as 100 million students between the age of five and 17 are estimated to have stopped attending classes. Additionally, armed conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen have left over 14 million students without any education.

This combination of a global pandemic, war, and poor-quality education is particularly concerning for a region that has historically performed at the bottom of international assessments of learning outcomes, such as the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

While there is little doubt that part of the push for better learning demands investing in early years and early grades, the immediate priority for MENA should be the transformation of post-secondary education. Youth unemployment rates in the region have been the highest in the world for over two decades, reaching 30% in 2017. This has been partly because of the mismatch between skills and labor market requirements in the region, where 60% of CEOs believe education systems are failing at providing students with the right skills for employment.

"Twenty-first century educators should no longer be concerned with control and authority, but rather critical thinking, project-based learning, and creativity."

A paradigm shift for post-secondary education

2020 was the year of the unmasking of higher education globally. During the pandemic, universities struggled to adapt quickly, shifting programs online without rethinking the pedagogy and learner experience for a new format, while continuing to charge students the same tuition as before.

What higher education institutions were slow to understand is that the world today is very different to the one the university was designed to serve more than a century ago. Education as we know it was born with the First Industrial Revolution, when the goal was to train a disciplined workforce for the new factories. But with the age of the internet came a new kind of student, one that takes more ownership over her own learning. Twenty-first century educators should no longer be concerned with control and authority, but rather critical thinking, project-based learning, and creativity. The so-called Generation Z, born after 1996, expects more from education than rote learning. They have a strong preference for self-learning and are more career-oriented and entrepreneurial.

A 2021 survey conducted by my non-profit organization, Re:Coded, with 60 young adults across six countries1 in the Middle East confirms that students in the region demand more from the education they receive. Around 55% stated that they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their university experience and virtually everyone said they believe it had not prepared them for the demands of the modern workplace.

What will the future of education look like?

The future of education will be defined by content, technology, and the internet. In a hyper-competitive and fast-evolving work environment, everyone will become working learners, “always flexing between working and learning,” as author Michelle Weise explains in her 2021 book Long-Life Learning: Preparing for Jobs that Don't Even Exist Yet. In practice, this means education systems will have to adapt to offer more flexible upskilling and reskilling pathways to students and workers alike.

Instead of consuming education in bundles in higher education institutions, students will increasingly seek to acquire or improve market-driven skills in a shorter time and for less money. The internet has enabled marketplaces for the smallest niches, where learn-as-you-go models allow education to take place everywhere, anytime, and be hyperspecialized. For example, coding bootcamps like Lambda School and cohort-based courses like AltMBA run completely online for classes of up to 150 students and teach ready-to-use skills in software development and marketing, respectively, for a fraction of the time and price of a college degree.

This does not mean that university diplomas will become worthless. Employers around the world, but particularly in the MENA region, still value the reputation of a higher education institution. However, universities will have to adapt to provide a better quality of education and retain students.

Despite the challenges the region faces, there are promising signs that education systems are starting to react to changes brought about by COVID-19. In March 2020, the Ministry of Education in Jordan acted quickly to launch an e-learning platform and two TV channels in partnership with EdTech companies Abwaab, Mawdoo3, and Jo Academy. In the UAE, the Ministry of Education, in cooperation with the Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University, created a free course to upskill teachers in just 24 hours to deliver education online, with more than 42,000 people completing the training in the first few weeks.

To sustain and scale these small gains, however, countries will need to invest in infrastructure and undertake more significant changes in education systems. Today, there are nearly 280 million people in the region (45% of the population) connected to mobile internet. For countries like Sudan and Yemen, internet penetration is lower than 30%. Internet connectivity also remains a challenge in rural and conflict-hit areas, as well as in urban areas during economic crisis, such as the recent power shortages in Lebanon. Broadband internet will be an indispensable commodity for education in the next five years and collapsing infrastructure will significantly stop the region from making progress in teaching and learning.

With education systems, the path is two-fold: reform outdated national curricula and reskill the teaching workforce. The range of courses on offer today still reflects the market demand for traditional preferences and theoretical approaches. At Re:Coded, we teach current and former university students in four countries in the Middle East who demonstrate little to no practical coding skills before joining our programs. But more importantly, curricula also need to be updated to reflect future needs. For example, the next iteration of learning systems might be powered by blockchain technology. Blockchain can help reduce cases of fraud in education, offer new paths to accreditation, and create better learning platforms. However, universities in MENA rarely teach it.

Finally, teachers should be retrained to provide a learning experience that is less dependent on repetition and memorization, and more focused on problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaboration. It is important to recognize that teachers in MENA and across the world have done a phenomenal job during the pandemic to keep students learning online. However, the next phase of education will require a shift from the teacher as the “sage on the stage” to the “guide on the side” to the “meddler in the middle,” as explained by educationalist Erica McWilliam. The teaching professional must learn alongside students and constantly improve her teaching based on data and feedback from her pupils.

Plato was correct: Necessity is the mother of invention. The COVID crisis has already pushed governments and businesses to make long-awaited improvements to education in the Middle East and beyond. This get-up-and-go effect will not last for long. But there is still time for countries in the region to reshape education in the next five years and join the revolution.

Marcello Bonatto is the co-founder of Re:Coded, a nonprofit training youth in the Middle East to start careers in technology.

Photo by Volkan Furuncu/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Endnotes

- Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, and Turkey.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.