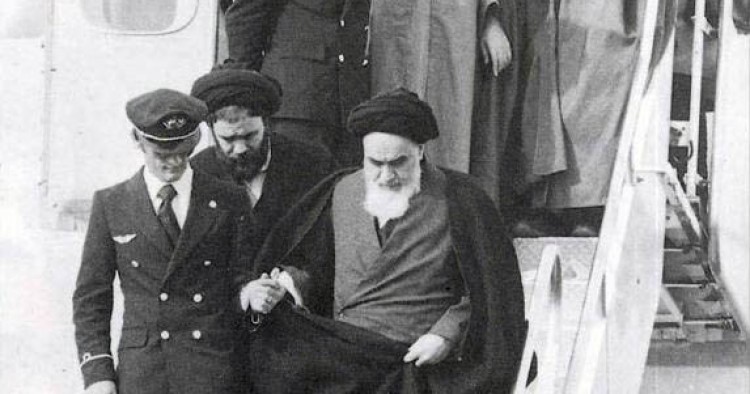

In the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Twelver Shi‘a Islam saw the crystallization of a major radical movement led by activist clerics and militant ideologues with a revolutionary agenda to establish an Islamist political order. The institutionalization of the political ideology of the velayat-e faqih or the “guardianship of the jurist,” advanced by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1900-1989), brought to the fore a new conception of Shi‘a government. This paradigm recognized the most learned cleric as the representative of the Twelfth Imam, whose eventual return is believed to culminate in the establishment of divine justice on earth. With the authority to participate in the political decision-making process, the new activist clerics emerged to help (and perhaps even shape) the first theocratic power in Shi‘a Islamic history, hence breaking away from the traditionalist quietist school of thought that had been dominant for centuries.

By and large, the 1979 Revolution included the different motivations of activists and groups that took part in it, and it is therefore not surprising that a variety of Shi‘a Iranian factions emerged in the aftermath of the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979. At the core of such factional rivalry was a vigorous debate over the question of clerical authority — the extent to which it can operate above the laws laid out by the legislative body, and, in essence, how best to achieve a political order that is both mundanely democratic and spiritually governed by divine law. As for dominant trends within Iranian Shi‘ism since the outbreak of the revolution, four significant historical phases can be identified: (1) Khomeinism (1979-1989); (2) re-constructionism (1989-1997); (3) factionalism (1997-2005); and, finally, (4) neo-Khomeinism (2005-to the present).

During the first nine years following the Iranian Revolution, the Islamic Republic evolved into a militant state directed with the essential aim of fulfilling God’s will on earth. While struggles with pragmatists and ideologues over state management continued to cause frictions within the regime, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) provided a new opportunity for the revolutionaries to solidify their radical agenda. During the war, the regime promoted a culture of martyrdom among Iran’s youth that primarily relied on symbols and mourning practices specific to Shi‘a cultural tradition. Such culture was shaped on an activist retelling of the martyrdom of the Prophet’s beloved grandson, Husayn, whose heroic death at the Battle of Karbala (680) was used to mobilize troops to the frontlines.

Not all Shi‘a Iranians accepted Khomeini’s vision of theocracy in the years following the revolution. For instance, Ayatollah Muhammad Kazem Shariatmadari (1904-1985), a senior Shi‘a cleric at the time, publicly opposed Khomeini, whose radical movement he regarded to be a deviation from true Shi‘ism. In response, the regime immediately stripped him of his religious authority and placed him on house arrest, a major affront to the clerical establishment that had never before seen a high-ranking jurist deposed by another cleric. In addition, the take-over of Qom, the country’s religious scholarly center, by state-sponsored activist clerics caused many non-Khomeinists to keep quiet for fear of retribution, thereby successfully containing dissident senior clerics and their followers.

The death of Ayatollah Khomeini initiated a second phase that largely gave way to the rise of pragmatists and technocrats who aimed to strengthen state control over the public sector for the purpose of establishing a functioning bureaucratic state and adopting a realist foreign policy in the post-war period. The initial push for state consolidation primarily involved a revision of the constitution that not only broadened the juridical and political power of the guardian jurist, but also allowed him to qualify for the post without being a marja or high-ranking cleric. The August 1989 appointment of a mid-level ranking cleric, ‘Ali Khamene’i, to the position of Supreme Leader introduced a major transformation in the classical function of the juristic authority that previously had recognized only the most learned mujtahid as the spiritual head of the Shi‘a community.

By the early 1990s, a loose coalition of dissident clerics, seminary students, university students, intellectuals, and middle-class professionals gradually formed a movement to challenge the conservative establishment. The presidential election of 1997, which brought to power the reformist Mohammad Khatami, gave momentum to this new coalition. The implication of the reformist’s ascendancy can be described in many terms, but one prominent feature is the escalation of political rivalry between reformists (who sought to limit the absolute authority of the Supreme Leader) and conservatives (who aimed to maintain political hegemony through repression and manipulation of the electoral process). The late 1990s came to represent the high point of post-revolutionary factionalism that gradually released Iranian civil society from the tight grip of Khomeinist authoritarianism.

In a swift reaction to reformists’ success and control over the direction of the theocracy, the 2004 parliamentary and 2005 presidential elections saw the advent of a new faction of Khomeinist ideologues, who aimed at reviving the militant values of the 1979 Revolution and set back Khatami’s achievements. The new movement, represented by the former mayor of Tehran, Mahmud Ahmadinejad, gave credence to a strategy to expand the role of ideologues, especially the Revolutionary Guard Corps, in the country’s economic and political activities, and, more importantly, curtail the progress of the reform movement in the electoral process. The rise of the neo-Khomeinists highlights the fractious nature of Iranian Shi‘ism in the post-Khatami era, and the significance of the legacy of Khomeini’s vision of the Islamic Republic in the way it continues to play a vital role in shaping politics in Iran. The intriguing issue here is how contestation over the formation of a just Islamic government, paradoxically, not only has helped perpetuate the political hegemony of the (neo) conservative Right but also helped reformists bolster aspirations for a new political order based on democratic norms and pluralism.

With the collapse of Saddam’s regime in Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent revival of Najaf, representing the center of quietist Shi‘a orthodoxy, Shi‘a Iran underwent an additional development. While reformists continued with their struggle to reinterpret Shi‘ism in a democratic light, Ayatollah ‘Ali Sistani, the most revered Shi‘a cleric in the world (based in Najaf), emerged as a leading quietist senior cleric to offer an alternative model of spiritual leadership. With an expanding religious network and a tight social organization operating on a global basis, coupled with an adherence to a clerical democratic tradition dating back to the Constitutional Revolution (1906-1911), Sistani’s positive influence over Iraqi democratic politics has served as an exemplary model of Shi‘a democracy to many Iranian reformists, which potentially could have an impact on the country’s political future.

After 30 years, the identity of Shi‘ism in Iran remains uncertain as new generations of reformists and hard-liners continue their rivalry with the determination to define the future of the Islamic Republic. What is certain, however, is that the future of Iran will be shaped by competing Shi‘a factions, each possessing its own distinctive interpretation of sacred tradition.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.