Summary

Unlike most other goods, the inflation-adjusted prices of oil and oil derivatives actually became cheaper in the years after the Syrian uprising and the loss of most of the country’s oil fields. Iran stepped in to fill the gap by shipping oil by sea through the Suez Canal. In recent months, however, these shipments seem to have ground to a halt, crippling regime-controlled areas. This paper examines several competing explanations for the slowdown in Iranian oil shipments, explores a range of possible responses for the Assad regime, and takes a closer look at the implications for the regime, its allies, and regular Syrians.

Executive summary

Before the 2011 uprising, Syria was a net oil exporter and demand for oil derivatives was met by refining crude domestically. In late 2012, however, the Assad regime lost control over most of the country’s oil fields to the opposition as Syria plunged into civil war. Yet, in the years after the uprising, oil derivatives became even cheaper in inflation-adjusted terms and remained largely available until late 2018. What accounts for this?

Iran stepped in to fill the gap. From 2013 to late 2018, it shipped an average of 2 million barrels a month to the Syrian regime by sea, with deferred payments, covering most of the country’s need for crude and helping to keep the regime afloat. Oil plays a central role in the economy, featuring in everything from production and electricity generation to heating and transportation. Without a steady supply of crude oil from Iran, the regime of Bashar al-Assad would have faced a complete economic collapse. Those days are now gone, however, and the situation has changed dramatically in the past few months. Oil shortages in April 2019 crippled regime-controlled areas and brought donkeys back to the streets of Damascus as Iranian crude oil shipments dwindled. There is considerable speculation about what caused the slowdown in shipments, and three of the most frequently cited explanations are:

- Iran stopped selling oil to the Assad regime on credit;

- The U.S. re-imposed sanctions on Iran’s oil exports in November 2018; and

- Third countries started blocking oil deliveries of any origin to the Syrian regime.

The third explanation is by far the most convincing, and there is strong evidence of an ongoing blockade on delivering oil, from anywhere, to the Assad regime. America is applying pressure on third countries to block oil from reaching Assad, with backing from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel, and this blockade is designed to coerce Assad, Iran, and Russia into making political concessions.

For their part, Assad and his allies are exploring five possible responses:

- Trying to continue to deceive the Suez Canal and Gibraltar authorities into allowing tankers carrying Iranian oil to pass;

- Using the Bukamal-Qaim land crossing to deliver Iranian oil through Iraq;

- Buying crude from the U.S.-allied Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in northeastern Syria;

- Delivering crude oil from Russia through the Black Sea; and

- Rationing Syria’s oil consumption.

Ultimately, the oil blockade is making the Syrian people, the Assad regime, Iran, and Russia worse off. All five possible responses are costlier — politically and financially — than the old approach of relying on uninterrupted Iranian oil shipments through the Suez Canal. The silver lining for Russia if it started delivering oil to Assad is that it could help crowd out Iran’s influence in Syria. But will Turkey allow Russian oil to reach Syria and risk being hit by U.S. sanctions? The international law governing the Turkish Straits is as murky as Turkey’s relations with the U.S. of late.

Continued disruption of the supply chain will result in further oil shortages in Syria, especially in the short term. Reductions in the supply of oil derivatives will deepen the country’s economic depression and hamper the tentative steps at reconstruction taken by Syria and Iran. Domestic oil prices will continue to rise given the excess demand, and life will become harder for those living in regime-controlled areas as the economy shrinks at a faster pace and higher prices push more people into poverty.

"In April 2019, oil shortages crippled the economy in regime-held areas and brought donkeys back to the streets of Damascus, leading to days-long queues in front of gas stations."

Background

According to the Syrian Bureau of Statistics, the price of a typical basket of goods and services rose eight-fold in the period 2010-17, while the price of a liter of regular gasoline rose only five-fold. As economists put it, the real or inflation-adjusted price of gasoline actually fell following the 2011 uprising and the civil war that ensued. In foreign currency terms, the price of a liter of gasoline dropped from 90 cents in 2010 to 41 cents in 2018, significantly below the prices in neighboring Lebanon, Jordan, or Turkey, all of which are at peace. Oil derivatives also remained largely available throughout the war.

The low price and steady flow of oil derivatives played a crucial role in preventing the total economic collapse of the Syrian regime. Oil features in everything from production and electricity generation to heating and transportation, and Iran’s supply of crude oil kept the Assad regime afloat.

That oil derivatives remained available from 2011 through 2018 and even became cheaper was not because Syria maintained its domestic oil production. Quite the contrary: The Syrian regime lost control over most of the country’s oil fields by late 2012, bringing production to a near halt and turning Syria into a net importer. (It was previously a net exporter, exporting an average of 4.6 million barrels a month over the period 2005-10.1) The not-so-secret stopgap was Iran, Assad’s ally, which ensured a steady flow of crude through the Suez Canal.

The CIA estimates Assad received 2.3 million barrels of crude oil a month over the period 2013-15, which covered all of Damascus’s needs.2 The trend continued beyond 2015, and satellite data suggests Iran was still delivering 1-3 million barrels of crude a month in 2018.3 Syria refines this crude oil domestically at its two refineries in Baniyas and Homs, which remain operational.

In April 2019, oil shortages crippled the economy in regime-held areas and brought donkeys back to the streets of Damascus, leading to days-long queues in front of gas stations.4 The situation has improved slightly since then as the government rationed the consumption of oil products and raised prices.

As opposed to almost 2 million barrels a month between 2013 and late 2018, satellite data showed that Syria did not receive any oil shipments from November 2018 until May 2019.5 Further deliveries of Iranian crude were made in June and July, but the amounts were not large enough to relieve the crisis.6

"The Syrian regime lost control over most of the country’s oil fields by late 2012, bringing production to a near halt and turning Syria into a net importer."

Why have Iran's oil shipments slowed?

There is a great deal of speculation about the cause, and commentators have attributed the decline in oil shipments to a variety of factors, each of which will be reviewed in turn.

Iranian lending to the Assad regime

According to both regimes, Syria buys oil from Iran on credit, not cash. Some sources, such as Reuters, have argued that the main reason for the slowdown in oil deliveries is that Iran has decided to stop extending credit to the Assad regime.7 In support of this view, Iran’s foreign minister, Javad Zarif, claimed in Damascus last April that “Syria has exhausted the option of persuading Iran to restart the credit line.”8

This is the least likely reason for the slowdown. The “credit line” to Syria is merely a cover for Iran’s economic support to Assad: It’s an attempt to appease public opinion in Iran as people grow anxious over their government’s economic and military involvement in neighboring countries. This has bubbled to the surface before, with protesters in 2018 shouting slogans such as “leave Syria alone, think about us.”9

Iran showers Assad with money to pay and equip militia fighters, reconstruct damaged public institutions, deliver aid, supply crude oil,10,11 and fund the central bank’s sales of greenbacks to prevent the Syrian pound from nose-diving. This article will focus on Iran’s supply of oil, setting aside these other expenses. Using CIA and satellite imagery estimates of Syria’s net imports of crude oil, and factoring in global oil prices at the time, Figure 1 (below) shows that the oil shipments to Syria alone are worth $10.3 billion, which eclipses the announced credit limit of $7.6 billion.12,13 The “credit line,” in short, is nothing but a cover.

Iran will not abandon Assad to his fate when it needs him most — at least as a negotiating card with the Trump administration. Supporting Assad by providing oil is one of the cheapest and most effective ways to keep the ailing regime in Damascus from crumbling. Despite offering oil at a discount, Iran’s crude and its fleet of tankers are begging for buyers around the world — to no avail.

The reimposition of sanctions on Iranian oil exports

The U.S. re-imposed sanctions on Iran, primarily targeting its oil sector, in November 2018 and issued sanctions waivers to allow a few third countries to buy its oil until May 2019.14 Countries that continue buying Iranian oil risk secondary sanctions from the U.S. The American position is, in essence, not only are we not dealing with Iran (aka primary sanctions), but we’ll punish others who do so as well (secondary sanctions).

The stringent U.S. sanctions on Iran’s oil sector and its National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) cannot on their own explain the slowdown in Iranian shipments to Assad though. As the NITC and the Iranian oil sector are under comprehensive sanctions, what would stop Iran from continuing to send shipments? Importers are usually the ones that refuse to buy Iranian oil because of concerns over U.S. sanctions. Iran is willing to sell its oil to whoever is willing to buy.

For its part, the Assad regime is by no means threatened by the U.S. sanctions on Iranian oil as it is already cut off from the global financial system and faces its own debilitating sanctions. For Syria, the cost of U.S. sanctions for importing Iranian oil, if there is one, is far less than the cost of not having crude oil at all.

Blockade on oil deliveries to the Syrian regime

Syrian and Iranian officials claim that several countries have been actively engaged in blocking oil deliveries to Syria — and they are right. Key countries such as Egypt and the British Territory of Gibraltar are under intense pressure from the U.S. to block oil deliveries to Assad. The U.S., in turn, is under pressure from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel. The countries blockading oil deliveries to Syria have different concerns and a common goal: to coerce the Syrian regime and its allies into changing their behavior and accepting serious concessions at the negotiating table.

While Saudi Arabia and the UAE are anxious about Iran’s role in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, they are particularly concerned about its involvement in Yemen. The pro-Iranian Houthi rebels there have been firing missiles at Saudi Arabia and the UAE since 2015, targeting infrastructure like airports, oil pipelines, and desalination plants.15

While Israel is concerned about the rise in Iran’s influence in the post-Arab Spring era, it is especially worried about Iran’s nuclear ambitions and its role in neighboring Syria and Lebanon. Israel has been targeting Iranian and Syrian military positions in Syria since the 2011 uprising.

Supporting the interests of its allies in the region, the U.S. is also pressuring Egypt and Gibraltar. In March 2019, the U.S. Treasury issued a stern warning to any institution or individual engaging in or facilitating deliveries of oil to the Syrian regime, be it of Iranian or any other origin.16 The Treasury’s warning mentioned the names of the tankers that have been involved in delivering oil to Assad over the past three years. The warning does not target oil exports from Syria or Iran, but rather, for the first time, Syria’s oil imports regardless of the origin.

Egypt's denial

Although Egypt denies blocking Iran’s oil deliveries to Syria,17 this is not the first time it has barred the Iranians from accessing the Mediterranean. In 2011, it turned back two Iranian warships near Jeddah, without making an official statement about the incident.18 Egypt regularly claims it does not use its control over the Suez Canal as a political tool so as not to scare shipping companies into using alternative routes.

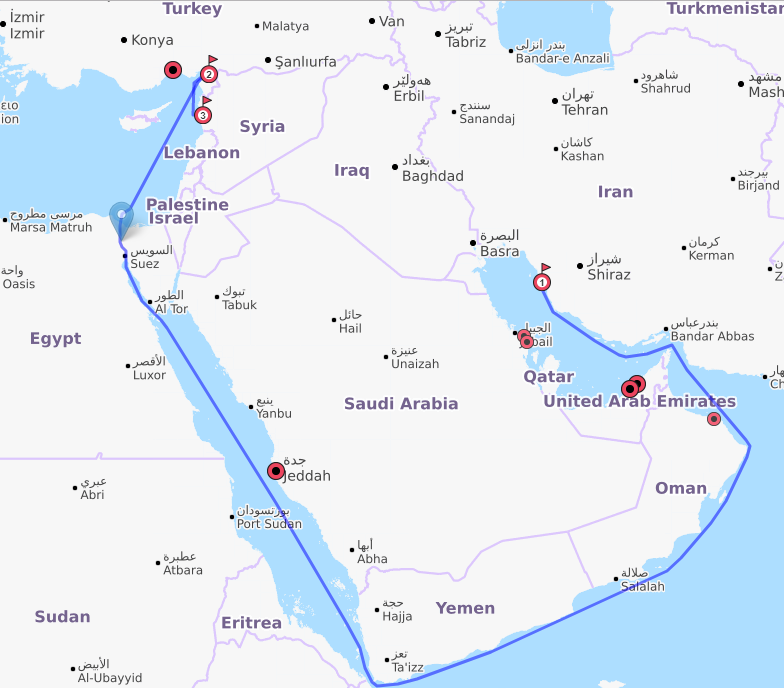

There are many reasons to believe Egypt is blocking oil deliveries to Syria, however. The only oil tanker that managed to make it to Syria between November 2018 and May 2019 seems to have told the Egyptian authorities it was heading to Turkey instead, which explains how it managed to traverse the Suez Canal. Satellite images showed that as the tanker reached the Mediterranean, it anchored in Turkey for three weeks before switching off its transponder, sailing to Syria’s Baniyas oil terminal, and unloading nearly a million barrels of crude oil. If Egypt did not mind the tanker going to Syria, why did it go to Turkey first, without unloading, and then head to Syria?19

between November 2018 and May 2019. (Author’s design, www.searoutes.com)

Unconfirmed reports also suggest Egypt detained another oil tanker attempting to deliver oil to Syria and arrested its six crew members on July 9.20

On July 4, Gibraltar authorities stopped an Iranian tanker, Grace 1, which was carrying 2 million barrels oil, from crossing to the Mediterranean. The route taken by Grace 1 (illustrated below) provides further evidence Egypt is blocking oil deliveries to Syria.21 For technical reasons, Grace 1 would not have been able to traverse the Suez Canal anyway due to its size.22 But this is probably not the reason why the tanker decided to go the long way around Africa. Instead, it was likely about cost: Using a large tanker was a way of making the painfully long journey less expensive. Iran is better off sending two oil tankers carrying a million barrels each through the Suez Canal than sending a single supertanker carrying 2 million barrels around Africa and through Gibraltar. Gibraltar authorities made it clear the tanker was stopped because of suspicions it was heading to Syria, not because it carried Iranian oil. Again, it’s clear Syria’s oil shortages are a result of the sanctions on its oil imports, not those on Iranian oil exports.

The countries blockading Syria seem to be determined not to allow oil to reach the government’s refineries. On June 24, Syria’s underwater pipelines used for transferring crude oil from tankers to the Baniyas refinery were sabotaged. It is unclear who was behind the attack.23

Iranian deliveries by sea

Now that the U.S. waivers on Iranian oil sales to all countries have expired, expect future Iranian tankers to face more difficulties in crossing the Suez Canal or Gibraltar as it will be very hard to convince the key third countries the oil shipments are not destined for Syria.

"Syrian and Iranian officials claim that several countries have been actively engaged in blocking oil deliveries to Syria — and they are right. Key countries are under intense pressure from the U.S. to block oil deliveries to Assad."

Possible responses to the blockade

So how will Assad and his allies respond to this situation? They have five possible options:

- First, trying to continue to deceive the Suez Canal and Gibraltar authorities into allowing tankers carrying Iranian oil to pass;

- Second, using the Bukamal-Qaim land crossing to deliver Iranian oil through Iraq;24

- Third, buying crude from the U.S.-allied SDF in northeastern Syria;

- Fourth, delivering crude oil from Russia through the Black Sea;

- Fifth, rationing Syria’s oil consumption.

Deception

Iran can deploy some of the shady shipping practices it learned during the 2006-15 round of sanctions on its oil sector. These include ship-to-ship oil transfers, shipping through other companies and disguising the destination, changing the names of tankers while at sea, or switching off transponders altogether.25

Recent technological improvements in tracking shipments and machine learning make it harder by the day for Iran to circumvent the sanctions on Syria’s oil imports.26 Iran might still be able to deliver some oil by sea to Assad, but not at the same pace as it did in 2013-18.

Ship it by land through Iraq

Instead of shipping by sea, Iran can try to deliver crude oil to Syria by land. Tanker trucks can carry an average of 200 barrels.27 Assuming Syria imports 2 million barrels a month, Iran will need to send 10,000 trucks a month to Syria. That’s a massive undertaking, and Iran and Syria simply don’t have the logistical capability to do it.

Trucks are also by far the most expensive means of transporting oil.28 Whether the Iraqi authorities would allow such trucks to pass through Iraq and the number of drivers that would be willing to make the dangerous journey are also uncertain.

Buy it from the SDF

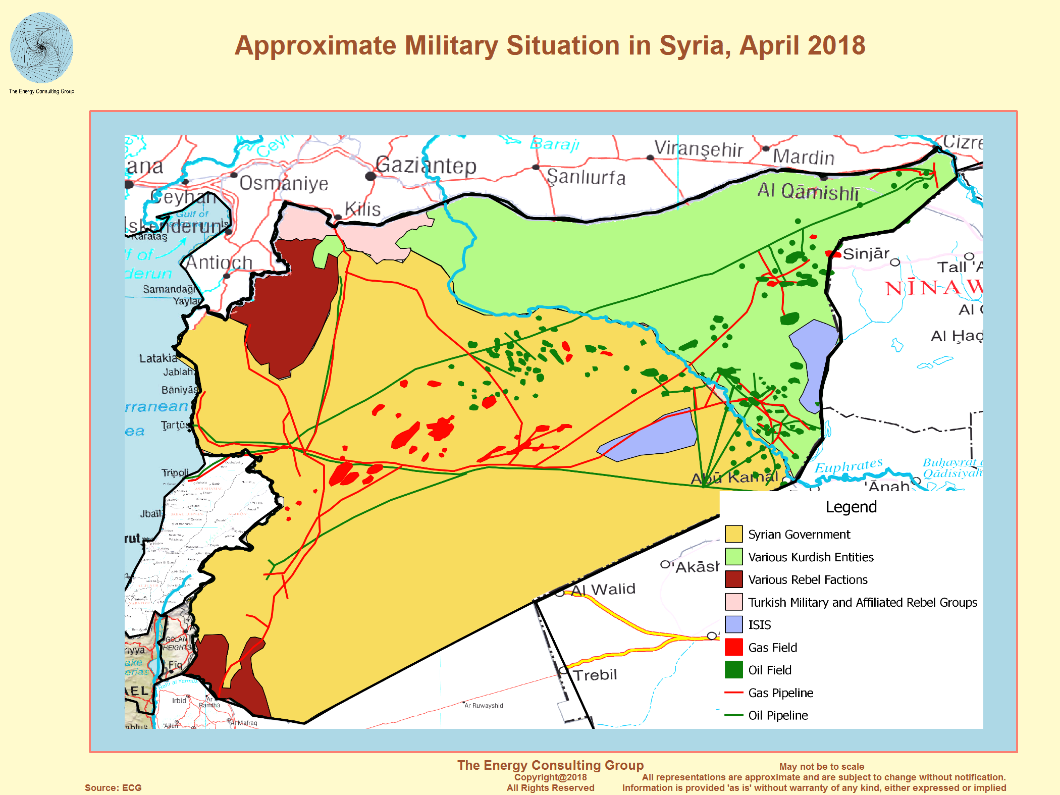

Syria and Iran view buying crude oil from the SDF (see below map, under “various Kurdish Entities”) as the last resort. Not only is the SDF allied with the U.S. against Assad, but it is also predominantly Kurdish. As is the case in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, a considerable share of Syrian Kurds have separatist aspirations, and Iran, as the primary financier of the Assad regime, would be reluctant to hand over large amounts of cash to the SDF.29

The SDF is estimated to be extracting an average of around 750,000 barrels of oil a month, which is barely enough to cover the needs of opposition-controlled areas. There are confirmed reports that the SDF has been selling crude to the regime in Damascus in exchange for oil derivatives and cash. However, the scale remains too small to alleviate the regime’s shortfall or to enrich the SDF.

There are also several logistical problems that prevent the SDF from delivering oil to regime-held areas. There are no pipelines connecting the two territories, so the two parties must rely on tanker trucks, further increasing the costs and limiting the amount of crude that can be transferred to the number of trucks willing to make the journey. The countries imposing the oil blockade on Assad are also likely to try to prevent such exchanges. On May 30, for example, the U.S. was reported to have bombed three tanker trucks delivering oil from SDF-controlled areas to the Assad regime.30

Rely on Russia

Russia and Iran have competing interests in Syria and keeping Assad in power for now is one of their few points of convergence. So far, Iran has provided Assad with more boots on the ground and kept him afloat financially, while Russia has focused on providing political backing and air support. Assad cannot afford to lose either Iran or Russia as they serve complementary purposes, and he has been playing both off of one another since the onset of the uprising to maximize his narrowing margin of control.

Iran remains Assad’s preferred supplier for oil as its support comes with fewer strings attached. In the long term, Russia is more invested in keeping its interests in Syria than in Assad himself, pushing more actively for a political settlement to the conflict and often urging Assad to respect the ceasefires and reconciliation deals that it brokers. As a result, Assad and Iran are not inclined to seek oil supplies from Russia, and they are willing to incur the additional time and expense of sending shipments the long way around Africa instead. They know the political cost of Russia’s oil might change the dynamics of power in Syria and crowd out some of Iran’s influence in the country.

Whether Russia wants to deliver oil to Assad and whether it can are different questions as well. Russia will have to pass through Turkey’s territorial waters to reach Syria. Article Two of the Montreux Convention (1936), which regulates the operation of the Turkish Straits (the Bosporus and the Dardanelles), states, “In time of peace, merchant vessels shall enjoy complete freedom of passage and navigation in the Straits, by day and by night, under any flag with any kind of cargo.” However, international agreements are open to interpretation. Is Turkey in a “time of peace” with Syria right now? An argument could be made either way.

Will Turkey uphold the blockade on Syria’s oil imports? What political cost will Russia have to pay? What we do know is that Turkey could risk being subjected to U.S. sanctions if it allows Russian oil tankers to reach Syrian refineries. The U.S. sanctions on Syria’s oil imports explicitly mention Russia.31 President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is already under intense pressure from the U.S. over his warming relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, and the U.S. government is considering imposing sanctions on Turkey for purchasing Russia’s S-400 missile defense system. Turkey will find itself in an awkward position of having to decide who its true ally is if Russia moves to supply oil to the Assad regime.

Ration oil consumption

Instead of, or in addition to, trying to increase its oil supply, as in the case of the previous four scenarios, Syria could also try to reduce its demand. In fact, it’s already taken measures to this end, including introducing electronic cards to ration the amount of gasoline each vehicle type gets to consume over a given period.32

"Ordinary Syrians will pay the heaviest price. Restricting oil deliveries to regime-held areas will make life harder for people as the economy shrinks at a faster pace and higher prices push yet more Syrians into poverty."

Implications of the blockade

The oil blockade is making the Syrian people, the Assad regime, and its allies all worse off.

For the regime, all five options for how to respond are costlier — politically and financially — than the old approach of relying on uninterrupted shipments of Iranian oil through the Suez Canal. It is in no position to pay for the oil it needs itself. Indeed, it has not been paying for the oil shipments Iran has provided since 2013, and is instead relying on borrowing from its “credit line.” Syria fails to cover its own expenses: On average, 38% of its government spending in the five budgets over 2012-16 came from deficit funding, i.e. printing money (the breakdown of revenues is not available for more recent budgets). Accordingly, the cost of supplying Syria with oil will continue to fall on Assad’s allies.

Despite efforts to reduce Syria’s demand by introducing fuel smart cards, the alternatives aimed at increasing supply might be insufficient to meet demand, at least in the short term, while Assad and his allies try to overcome the logistical difficulties.

The decline in the supply of oil derivatives will deepen Syria’s economic recession and hamper the efforts at reconstruction that the regime and Iran have taken in recaptured areas such as Aleppo, Homs, and the suburbs of Damascus.

To maintain its overall revenue and given the decline in the quantity of available oil derivatives, the Syrian regime will likely raise prices. The increase will probably be small as people cannot afford steep price hikes, ultimately resulting in lower government revenue.

The increase in excess demand and the rise in prices will make it more attractive for corrupt officials to sell oil derivatives in the black market, further fueling public anger against the regime.

Ordinary Syrians will pay the heaviest price. Restricting oil deliveries to regime-held areas will make life harder for people as the economy shrinks at a faster pace and higher prices push yet more Syrians into poverty.

Endnotes

1. “Middle East: Syria,” The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, accessed June 6, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sy.html.

2. “Middle East: Syria.”

3. Leila Gharagozlou and Tom DiChristopher, “Iran Appears to Be Restarting Oil Exports to Syria as Trump Ups Pressure,” September 5, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/05/09/iran-appears-to-be-restarting-oil-expor….

4. Amr Salahi, “Syrians Use Horses and Mules amid Unprecedented Fuel Crisis,” Alaraby, accessed June 12, 2019, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2019/4/18/syrians-use-horses-and….

5. “Iran Sent Oil Shipment to Syria, Easing Fuel Crisis: Source,” Reuters, May 10, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-security-oil-idUSKCN1SG1FK.

6. “Over One Million Barrels of Suspected Iranian Oil to Be Unloaded in Syria’s Baniyas: Report,” AMN - Al-Masdar News, June 28, 2019, https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/over-one-million-barrels-of-suspec….

7. “Iran Sent Oil Shipment to Syria, Easing Fuel Crisis.”

8. “Syria Face Oil Shortage After Iran Cuts off Credit Line,” Iran Focus, April 18, 2019, https://www.iranfocus.com/en/iran-a-neighbours/syria/33464-syria-face-o….

9. Liz Sly, “Protests Threaten Iran’s Ascendant Role in the Middle East,” The Washington Post, January 5, 2018, sec. Middle East, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/protests-threaten-irans-ascendant-….

10. “Middle East: Syria.”

11. Where the CIA suggests Syria imported 2.5 million barrels a month in 2015, satellite tracking companies, such as TankerTracker, suggest the country has been receiving 1 to 3 million barrels a month.

12. Sami Moubayed, “Syria Leases Mediterranean Port to Iran,” Asia Times, April 5, 2019, https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/04/article/syria-leases-mediterranean-po….

13. The estimates of crude oil net imports from the CIA are available only until the end of 2015. Given the control map over oil fields and reports from satellite tracking companies, I assume that the net imports continued at the same level of 2014-15 through the period 2016-18. I apply Dubai Crude price to calculate the market value of Iran’s oil exports to Syria due to data availability. Dubai and Iran crudes are quite similar. The estimates of the value of Syria’s oil imports do not factor in any oil shipping costs for simplicity.

14. Humeyra Pamuk and Lesley Wroughton, “U.S. to End All Waivers on Imports of Iranian Oil, Crude Price Jumps,” Reuters, April 22, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran-oil/us-to-end-all-waivers-o….

15. Jared Malsin, “Iran-Allied Houthis Expose Holes in Saudi Arabia’s Missile Defense,” The Wall Street Journal, June 25, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-allied-houthis-expose-holes-in-saudi-…

16. “OFAC Advisory to the Maritime Petroleum Shipping Community: Sanctions Risks Related to Petroleum Shipments Involving Iran and Syria” (Department of the Treasury, the United States, March 25, 2019), https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/s….

17. “Would the Fuel Crisis Stifling the Regime-Held Areas Uproot ‘Assad’?,” Call Syria, April 17, 2019, https://nedaa-sy.com/en/week_issues/75.

18. Avi Issacharoff, “Report: Egypt Blocked Iran Ships from Entering Suez Canal,” Haaretz, via Reuters, February 17, 2011, https://www.haaretz.com/1.5123832.

19. Gharagozlou and DiChristopher, “Iran Appears to Be Restarting Oil Exports to Syria as Trump Ups Pressure.”

20. “Egypt Detains Iran Oil Tanker, Arrests 6 for Espionage,” Middle East Monitor, July 9, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190709-egypt-detains-iran-oil-tanke….

21. “Gibraltar Detains Syria-Bound Super Tanker with Iranian Oil,” The Washington Post, accessed July 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/syria-bound-oil-tanker….

22. Some sources claim that Grace 1 could have used the Suez Canal if it emptied its load before entering the Canal and later loaded it again after passing. However, that would have meant using a pipeline that is partly owned by Saudi Arabia, which does not allow utilizing the pipeline by the Iranians.

23. “Syria Underwater Oil Pipelines Sabotaged amid Fuel Shortages,” Middle East Monitor, June 24, 2019, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190624-syria-underwater-oil-pipelin….

24. Sune Engel Rasmussen, “Iraq to Open Vital Border Crossing with Syria,” The Wall Street Journal, March 18, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iraq-to-open-vital-border-crossing-with-sy….

25. “OFAC Advisory to the Maritime Petroleum Shipping Community: Sanctions Risks Related to Petroleum Shipments Involving Iran and Syria.”

26. “How to Stop Iran Oil-Sanction Busters? Take 50 Million Photos a Day,” The Wall Street Journal, November 1, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/video/how-to-stop-iran-oil-sanction-busters-take-50….

27. Megan E. Hansen, “Pipelines, Rails, and Trucks- Economic, Environmental, and Safety Impacts of Transporting Oil and Gas in the U.S.” (STRATA, n.d.), https://www.strata.org/pdf/2017/pipelines.pdf.

28. E. Hansen.

29. David Butter, “Syria Desperately Seeks Fuel,” Petroleum Economist, March 28, 2019, https://www.petroleum-economist.com/articles/politics-economics/middle-….

30. “US Forces Blow Up Three Oil Tankers In Syria Enforcing Oil Embargo,” OilPrice.com, accessed July 11, 2019, https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/US-Forces-Blow-Up-Th….

31. “OFAC Advisory to the Maritime Petroleum Shipping Community: Sanctions Risks Related to Petroleum Shipments Involving Iran and Syria.”

32. Sarah El Deeb, “Syria Fuel Shortages, Worsened by U.S. Sanctions, Spark Anger,” AP News, April 16, 2019, https://apnews.

Photos

Main photo: Iranian supertanker Grace 1 off the coast of Gibraltar on August 15, 2019. (JORGE GUERRERO/AFP/Getty Images)

Contents photo: People battle a blaze next to an oil well in an agricultural field in the town of al-Qahtaniyah, in the Hasakeh province near the Syrian-Turkish border on June 10, 2019. (DELIL SOULEIMAN/AFP/Getty Images)

First pull quote photo: Syrians line up to fill their cars up with petrol at a gas station in Damascus, Syria, on April 23, 2019. (Xinhua/Ammar Safarjalani via Getty Images)

Second pull quote photo: A Syrian worker is pictured on October 31, 2018 at a primitive oil facility in the town of Zardana in the countryside of the northwestern Syrian Idlib Province. (AMER ALHAMWE/AFP/Getty Images)

Third pull quote photo: A British Royal Navy ship (L) patrols near supertanker Grace 1 suspected of carrying crude oil to Syria in violation of EU sanctions after it was detained off the coast of Gibraltar on July 4, 2019. (JORGE GUERRERO/AFP/Getty Images)

Fourth pull quote photo: A Syrian man stands by a vegetable stall in an open-air market in the rebel-held town of Douma, on the eastern outskirts of Damascus on May 23, 2017. (AMER ALMOHIBANY/AFP/Getty Images)

About the author

Karam Shaar is a macroeconomist, with a BA from the University of Aleppo, an MSc from University Putra Malaysia, and a PhD from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Karam is from Aleppo, Syria, and he is interested in the political economy of the Middle East. He was actively engaged in the civil uprising demanding democratic reforms in his country in 2011 and 2012. Later in Malaysia, he volunteered with the UNCHR, teaching and fundraising to help refugees. He also worked as a researcher at the Aleppo Project where he focused on the economics of the civil war in the city. In New Zealand, he organized several events to raise public awareness about the war in his country. He currently works as a Senior Analyst at the New Zealand Treasury. The views expressed in his writings at MEI are his own, and this work is done in his capacity as an independent researcher and has no relation to the New Zealand Treasury.

He can be followed on Twitter @KaramSh88 and Facebook www.facebook.com/karam.shaar

About the Middle East Institute

The Middle East Institute is a center of knowledge dedicated to narrowing divides between the peoples of the Middle East and the United States. With over 70 years’ experience, MEI has established itself as a credible, non-partisan source of insight and policy analysis on all matters concerning the Middle East. MEI is distinguished by its holistic approach to the region and its deep understanding of the Middle East’s political, economic and cultural contexts. Through the collaborative work of its three centers — Policy & Research, Arts & Culture and Education — MEI provides current and future leaders with the resources necessary to build a future of mutual understanding.