After 11 years of war in Syria, the COVID-19 pandemic, and an economic crisis, education for Syrian children and youth has been severely disrupted, leaving more than 2.4 million out of school. Failure by international governments to act urgently endangers the prospects of stabilizing Syria and facilitating recovery. Disruptions to education programming will have both immediate and long-term negative consequences for Syria's children and the country's future. Governments and donors must initiate a stronger push to facilitate a more sustainable and quality education response to help stabilize Syria and facilitate its recovery.

Contents

Overview of the Sector

Current Education Implementation in Syria

Ongoing Humanitarian Needs in Syria

General and Cross-cutting Humanitarian Needs

Education Needs by Geographic Hub

Challenges to Education Service Delivery Across Syria

Delays in Adopting an Early Recovery Approach to Education

Unsustainable Funding Approach

The Challenge of Data Management and Disaggregation per Region

Failure to Prioritize Education in Syria will Continue to have Devastating Consequences

Recommendations to Donors for Education Coordination and Funding

Executive Summary

- After 11 years of war in Syria, the COVID-19 pandemic, and an economic crisis, education for Syrian children and youth has been severely disrupted, leaving more than 2.4 million out of school.

- Around 6.1 million Syrian children rely on formal and non-formal education services provided by humanitarian actors in coordination with state officials in territory held by the Government of Syria (GoS) and de-facto authorities in areas outside of government control.

- The fragmentation of Syria throughout the war has inhibited a standardized education response, despite authorities’ efforts to harmonize curricula. Thus, education needs and challenges often differ significantly across the main hubs of Syria based on the particularities of each region.

- However, across all areas of Syria, education provision faces some substantial cross-cutting challenges, including:

- Delays in adopting an early recovery approach to education adapted to the protracted nature of the conflict, which would entail more strategic, long-term planning.

- An unsustainable, short-term funding approach that results in major gaps in programming, de-prioritization of quality control and monitoring of learning outcomes, and an insufficient amount of resources for education.

- Poor data management and disaggregation of information per region, compromising accuracy of data analysis and preventing more nuanced assessments of education trends and needs across the Whole of Syria (WoS).

- Failure of donors to prioritize education in Syria and address ongoing challenges will have devastating consequences.

- In the immediate future, disruptions to education programming are correlated with increased rates of child labor, child marriage, and potentially armed recruitment of children, among other child protection concerns.

- In the long term, disrupted education can reduce life expectancy, inhibit economic growth, prevent transitions out of poverty, reinforce prolonged dependence on aid, and substantially diminish the capacities of Syria’s children and youth from eventually engaging in the rehabilitation of their country.

- Thus, governments and donors must initiate a stronger push to facilitate a more sustainable and quality education response — in coordination with the U.N., NGOs, and relevant authorities — to help stabilize Syria and facilitate its recovery.

Introduction

The world’s attention has increasingly shifted away from Syria, as much of the country’s 11-year armed conflict has drawn down, the COVID-19 pandemic has become an enduring global reality, and other crises, like those in Yemen, Afghanistan, and now Ukraine, have come to the fore. Yet, an estimated 14.6 million vulnerable Syrians continue to face one of the most devastating humanitarian crises in the world.1 A crucial component of the humanitarian response to this ongoing crisis involves the implementation of emergency education services, upon which approximately 6.1 million Syrian children and youth rely.2 Systematic attacks on schools, forced displacement of students and teachers, and COVID-related disruptions have made it challenging for humanitarian organizations to ensure consistent access to education for Syrian children. Recent data show that 2.4 million children are out of school,3 with many more at risk of dropping out.4 Moreover, the United Nations estimates that effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will reverse nearly 20 years of progress in education completion around the world.5 The implications of such global disruptions after more than a decade of war in Syria are especially bleak.

The impacts of these challenges on the education of Syrian children are varied and complex. Some of the long-term implications could entail reduced life expectancy and loss of human capital and economic productivity. The short-term effects of disrupted education on the safety and wellbeing of Syrian children are more immediately devastating: Loss of access to school too often leads to spikes in child labor, child marriage, and other major protection concerns. To make matters worse, humanitarian funding for the Syria crisis has declined amid intense competition for global aid. This sharp decline in education access and outcomes is a complete reversal from the pre-war potential of youth, who were once hailed throughout the region as a source of positive political, economic, and social change. Before the conflict, the country boasted a 98% attendance rate at the primary level and literacy rates at nearly 90%6 for both men and women.7 Today, a child born in the first year of the Syrian war will be approaching their 12th birthday and may have already missed several years of formal education, becoming part of the ever-growing “lost generation” of Syrians.

This analysis first provides an overview of the “education in emergencies” sector and its implementation in Syria, then examines the humanitarian needs of Syrians — particularly in regard to education — and, finally, explores the main challenges to effective education service delivery within the Syrian humanitarian response. Drawing on nine interviews with humanitarian practitioners across all of Syria’s geographic areas of operations, as well as a number of secondary U.N. and NGO reports, this analysis will provide recommendations to donor governments and their partners to address obstacles to effective education delivery in Syria and accelerate an early recovery approach.8 Governments and donor agencies must recognize that education is a critical element of Syria’s eventual stabilization and sustainable recovery, and requires urgent action.

Education in Emergencies

Overview of the Sector

In any humanitarian crisis, education is often one of the first services to be disrupted and among the last to be restored.9 The COVID-19 pandemic has caused “the largest disruption of education systems in history.”10 The right to education is a fundamental right enshrined in international law, including the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), to which Syria is a signatory. Yet, it can be incredibly challenging to deliver in the midst of an emergency, with many risks involved, such as perpetuating conflict dynamics. Although education is often marginalized in overarching discussions on humanitarian needs, its role must not be underestimated. If implemented effectively, education can play a key role in helping societies engaged in protracted crises to emerge from war and to build back better.

In the early 2000s, education in emergencies (EiE) was conceptualized as a field of research and practice made up of those working to support education in crisis-affected and developing contexts.11 This paved the way for the development and launch of the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for Education in 2004.12 After activation of the cluster system13 — a mechanism for coordinating delivery of services in a humanitarian context, led by the U.N. — advocacy efforts led to the inclusion of a cluster dedicated to education in 2007, re-affirming the importance of education services in humanitarian responses.14 In an emergency, education interventions center on physical and psychosocial protection for children as a first step, ensuring schools are entry points for services, such as health and nutrition, and deliver life-saving messages to children (e.g., about health, hygiene, and disaster preparedness). Content focused on enhancing learning outcomes follows because children cannot learn until their physical and psychosocial needs are addressed.

After the initial emergency, global minimum standards advise that there should be a transition to the formal pre-crisis curricula, with the support of accelerated and catch-up curricula when needed. Unfortunately, the protracted nature of many conflicts we see today has placed learning in limbo with exclusively temporary measures to keep children learning. In ideal circumstances, when the initial emergency phase of a crisis has subsided, education programming calls for the adoption of an early recovery approach within the existing humanitarian response. Early recovery is not a “phase,” but rather a “vital element of any effective humanitarian response.”15 Emergency education activities should align with early recovery principles, such as school rehabilitation and system-strengthening, including continuous support to education personnel.16 Given the prolonged nature of the conflict in Syria, it is critical to prioritize early recovery programming in education for the nearly 7 million children and education personnel in need of education support.17

Current Education Implementation in Syria

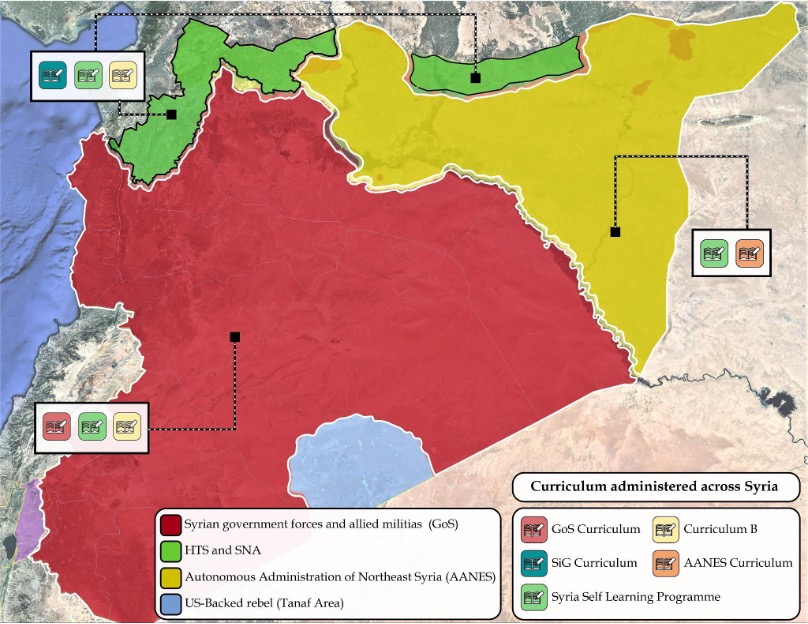

Education in Syria today includes formal18 and non-formal education.19 Formal education facilitates learning for children ages 6 to 17 at the basic education (grades 1 to 9) and secondary level (grades 10 to 12). Additionally, there are some opportunities for early childhood education, but they are limited.20 Harmonization and standardization of materials used for teaching and learning is a key issue across the country (see Figure 1, which maps where each curricula is reportedly used21).

Due to the political fragmentation of the country, there are a number of curricula used throughout Syria today — referred to as either “formal” or “non-formal”22 — primarily aimed at children in grades 1 to 9. Formal education, according to reports and interviews with education practitioners, refers to the curriculum of the Government of Syria (GoS), as well as a modified version23 of it used in northwest Syria, outside of GoS control. In this report, non-formal education refers to structured, institutionalized learning that supports either a return to formal education, accelerated learning programs in order to participate in national assessments, or interventions that facilitate building technical and cross-cutting skills (ideally relevant to local job markets) for those not likely to return to formal schooling. This includes the Syria Self-Learning Program, which is a catch-up program widely adopted humanitarian actors in non-formal education centers.24 Additionally, “Curriculum B” is an accelerated version of the GoS curriculum and is used in both non-formal learning centers25 and formal schools.26 Use of other remedial learning packages to support out-of-school or in-school students, developed by implementing NGOs, has also been reported.27 Throughout areas under the de facto control of Kurdish authorities, a Kurdish and Syriac curriculum is also reportedly used in schools run by education authorities in the northeast — but not learning centers run by humanitarian actors.28

Figure 1. Curricula administered in Syria29

Ongoing Humanitarian Needs in Syria

General and Cross-cutting Humanitarian Needs

Despite a decline in active armed conflict in recent years, approximately 6.9 million Syrians have been internally displaced as of early 2022.30 The global pandemic and the economic crisis that has emerged within Syria over the past couple of years have compounded the vulnerabilities that Syrian populations already suffered as a result of conflict and displacement. Nearly 12 million people were reported to be food insecure in 2021.31 More than half of Syrians are estimated to be unemployed, as the value of the Syrian pound, which plummeted by more than 80%, continues to depreciate.32 Over $4 billion in aid33 has been requested by humanitarian actors (as part of the global U.N.-led response) to provide life-saving needs via the Whole of Syria (WoS) mechanism this year, which aims to deliver services across the country via Damascus and the cross-border response based in Gaziantep, Turkey.

Syrian children and youth continue to face enormous protection risks and bear the brunt of the conflict on every level. Over 1,400 grave violations against children were verified in 2021,34 including nearly 300 deaths,35 attacks on schools, and recruitment of children for combat.36 Survivors face a shattered economy and exposure to alarming levels of child exploitation, among other protection concerns.37 After years of ongoing conflict, only one-third of schools in Syria are fully functional.38 Half of out-of-school children (OOSC) have never entered school, and school dropouts increase sharply after the age of 11, in particular for boys because their families need them to enter the workforce.39 Age-appropriate learning is more out of reach than ever, especially for secondary-level youth. Additionally, the protection and security threats children and youth face in their daily journey to school puts them at further risk.40 The education sector’s severity rankings indicate the situation and needs are highest in Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus provinces, respectively.41 Humanitarian staff, who are also members of the crisis-affected community, continue to reiterate the importance of strong community leadership in education to combat the influence of armed actors seeking to politicize education across the country.

Education Needs by Geographic Hub

GoS-held Territory: GoS-held territory includes parts of Ar-Raqqah, Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo, and al-Hasakah governorates, and the entirety of Homs, Hama, Dara’a, Quneitra, As-Suwayda, Damascus, and Rural Damascus provinces.42 The Damascus hub channels humanitarian funding to the aforementioned areas. GoS territories — constituting 67% of Syria43 at the time of writing — have experienced less armed conflict in recent years (with the exception of clashes in the southern province of Dara’a in late 2021,44 which impacted education in the province45). However, regions under the control of the GoS have not been immune to the compounded economic challenges felt across the country, including currency devaluation and skyrocketing prices for food and essential items. Educational activities implemented through the Damascus hub mirror those in the other territories, although the key difference is the presence of the Syrian Ministry of Education (MoE) to lead and support education service delivery.

Of the regions under GoS supervision, Aleppo, Damascus, and Rural Damascus are where “catastrophic” education conditions46 are mostly concentrated, including high student-teacher ratios (over 100 students per teacher) and long, often unsafe, journeys to schools.47 The highest severity rankings signify high dropout rates and limited return to learning post-initial COVID-19 closures. Additionally, age-appropriate education opportunities for youth and children with disabilities (CWDs) are extremely limited.48 One aid worker based in the Damascus hub said that economic sanctions levied by the U.S. and European countries have impacted the country’s youth education programming, with agencies reporting difficulties in obtaining materials and equipment for skills and vocational programs. Additionally, non-formal educational programs have been difficult to implement, as some online learning platforms and websites are inaccessible in Syria due to sanctions. Although the U.S. and the EU have endeavored to provide humanitarian exceptions to sanctions and remain the largest providers of aid to Syria, aid organizations have reported limited options for procurement and banking restrictions due to directly sanctioned entities, as well as overcompliance that stems from fear of doing business with potential targets of sanctions.

Coordination in areas under different authorities also poses challenges. The provinces of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakeh have territory both in and out of GoS control, which have high rates of OOSC and severe accessibility challenges for implementing actors; different authorities further contributes to the lack of harmonization and resources needed to deliver quality, relevant education.49 Finally, in terms of teacher salaries, unlike other territories of Syria, incentives are reportedly paid on a regular basis to teachers; however, incentives are lowest in GoS-territory, at approximately $35 per month.50

Northwest Syria (NWS): NWS response includes Idlib Province and parts of northern Aleppo. NWS is characterized by a heavy presence of armed actors with varying levels of interest and ability to impose their authority on education service delivery by humanitarian actors.51 This includes a plethora of rebel groups and armed factions, including Hay’at-Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the al-Qaeda offshoot in Idlib. Part of the northern Aleppo Governorate, west of the Euphrates (northern Aleppo countryside), remains under the direct military control of the Government of Turkey (GoT) and its supporting factions. The latest findings52 report that children in NWS face more devastating risks and violations of their rights than in any other part of the country, including attacks on schools, recruitment of children into armed groups, child labor, and exploitation.53 Aleppo and Idlib are the two governorates with the highest needs based on the sector’s severity ranking. In the NWS response, there are over 800,000 OOSC, a number that has grown by nearly 40% since 201954 due to increased displacement resulting from armed conflict and deplorable economic conditions. The dearth of livelihood opportunities, compounded by the country’s economic crisis, continues to play a major role in school-age children and youth whose access to formal or non-formal education has substantially diminished, thus increasing their exposure to negative coping mechanisms.55

Parents who are unable to secure consistent access to income face immense pressure to send their children to work or marry them off before the age of 18.56 Beyond the challenges external to education, there are reports that teachers have not been paid57 for nearly two years.58 Moreover, at different stages in the crisis, teachers in the north of the country have been compelled to travel to GoS-held territory to collect their monthly salaries as public sector employees, although this has become increasingly rare.59 A lack of age-appropriate schools has also contributed to high rates of OOSC in NWS.60 Secondary education services have been largely underfunded, including incentives for secondary-level teachers and funding to support facilitating secondary-level examination in GoS-territory for learners in NWS.61 It is also important to note that the areas of NWS under the supervision of Turkish forces have limited funding partly due to a lack of appetite from donors to prioritize this contentious geographical area.62 The GoT does implement some education interventions, including providing support to schools delivering the curriculum known as the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) curriculum.63

Interviews conducted for this report revealed that the criteria for what key donors are willing to fund in education in NWS continues to narrow. For example, one key donor that funds almost half of learning facilities in NWS does not fund education activities beyond grade 4, leaving lower and upper-secondary level learning activities severely under-funded.64

Territory under the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria (AANES): AANES includes most of Ar-Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, and al-Hasakah governorates, with territory under the supervision of the GoS in each.65 The security situation in AANES remains unstable. Reports of intercommunal violence in several camps, including al-Hol and others, have increased in early 2022.66 Unlike the humanitarian response from the NWS and GoS-territory, North East Syria (NES) no longer has a U.N.-mandated cross-border mechanism or official U.N. presence.67 Therefore, a group of international and Syrian NGOs has taken over the coordination of the humanitarian response under the umbrella of the NES NGO Forum, including Sector Working Groups such as the Education Working Group. The region faces complexities in accessing aid and inclusion of its needs in key national documents, such as the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP).68

NES is characterized by large pockets of OOSC, with oversaturation of education service delivery in some formal camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) using catch-up curriculum, while other informal settlements remain under-serviced.69 Several of the country’s largest IDP camps are located within this region. Approximately 1.4 million children and youth are in need of education services in AANES.70 The various curricula taught (see Figure 1) designate the language of instruction for learners in AANES. As with NWS, lack of age-appropriate learning opportunities in NES has contributed to high rates of OOSC.71 Activities using a catch-up curriculum are administered in English and Arabic, but authorities in AANES implement their own curricula in Kurdish72 as well as in the Syriac language.73 There is anecdotal evidence that administering Kurdish curricula in AANES has pushed some parents to move to the GoS-held part of al-Hasakah province in order to access the recognized, Arabic-language GoS curricula.74 This issue has been echoed in other reports and will likely continue based on the quality of education services delivered in AANES.75

The sporadic location of formal and informal camps and settlements has made it challenging for education service providers, who are often based in the central al-Hasakah Governorate, to properly assess needs and deliver services in these pockets.76 While the NES hub participates in the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)-led country-wide HRP, it is not eligible for pooled funds managed by OCHA due to the exclusion of the NES from the U.N. Security Council cross-border resolution. Therefore, funds for the response plan are granted via bilateral funding to NGOs registered in AANES, substantially limiting the available funding and range of options for other NGOs.

While curricula and quality of teaching and learning should be prioritized by donors, AANES education actors interviewed for this report shared that the immediate priority is to significantly reduce the number of OOSC through outreach and improved access, and increase children and youth participation in catch-up programs for eventual transition to formal learning.77

“To prevent disruptions in education service delivery and to design education interventions with long-term objectives in mind, education should be implemented and funded within the framework of an early recovery approach.”

Challenges to Education Service Delivery Across Syria

Delays in Adopting an Early Recovery Approach to Education

A stable and safe Syria is dependent on its children and youth. Post-conflict rebuilding of the economy and limiting long-term dependence on aid will require a population equipped with basic education and technical and vocational skills.78 This is urgently needed, as the current workforce in Syria is aging and, at the same time, critical skill-building of youth continues to be neglected.79 Regardless of geographic or political shifts that may occur as a result of future rounds of armed conflict in Syria, the needs of children and youth will only increase unless serious steps are taken toward long-term recovery of human capital loss in Syria. An early recovery approach should therefore be viewed as an investment in people to make systems more resilient.

The global minimum standards for education do not delineate a clear list of education activities to be implemented at the different phases of a crisis (from its onset to a protracted state to the development/post-conflict period). Although education interventions are clearly critical in emergency contexts, they are often mislabeled as development activities and therefore excluded from funding mechanisms that prioritize emergency aid from donors. This lack of clarity is also reflected in crisis-affected communities, which are increasingly dissatisfied with “temporary” measures such as tented schools and indefinite use of catch-up curricula.80 According to interviews conducted for this analysis, donors and implementing agencies in Syria often have different understandings of what early recovery entails. Per guidance from the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), early recovery education activities are not far off from what could be or is included in today’s education response in parts of Syria. However, the response has yet to enshrine a dedicated early recovery framework for the sector and systematically adopt an early recovery approach across all education activities implemented in the country. Some existing activities that would fit into an early recovery approach include partial rehabilitation of schools and “system” strengthening activities that target education personnel, under the auspices of education authorities, but with an increased focus on enhancing local community ownership. Community ownership in Syria is critical, given that de facto and national authorities have had varying levels of interest and ability to lead education service delivery.81

To prevent disruptions in education service delivery and to design education interventions with long-term objectives in mind, education should be implemented and funded within the framework of an early recovery approach, which combines humanitarian programming with development principles. The application of such a framework should be collectively developed and recognized by all major donors, and be reflective of feedback from U.N. and NGO coordination actors, which should integrate needs voiced by the crisis-affected community. Such a framework would progress at different stages in each geographical hub, given the different contextual needs, but all should work toward it as an eventual goal. Donors and grantees can lay the groundwork by coming to a more well-defined, mutual understanding of what the early recovery “approach” should look like in Syria in relation to education, with donors demonstrating flexibility given that some parts of Syria are more volatile than others — as well as potential political shifts.

Unsustainable Funding Approach

The unsustainability of the current education response is not only linked to the approach, but also to funding. This entails limited multi-year funding and vulnerability of already limited funding and suspensions of activities when frontlines change. There is also little space to satisfy donors’ desire for different activities while also staying within OCHA’s humanitarian response framework and process, as the humanitarian response planning process is largely standardized within Syria and globally (in terms of format, data collection, and activities included.)82

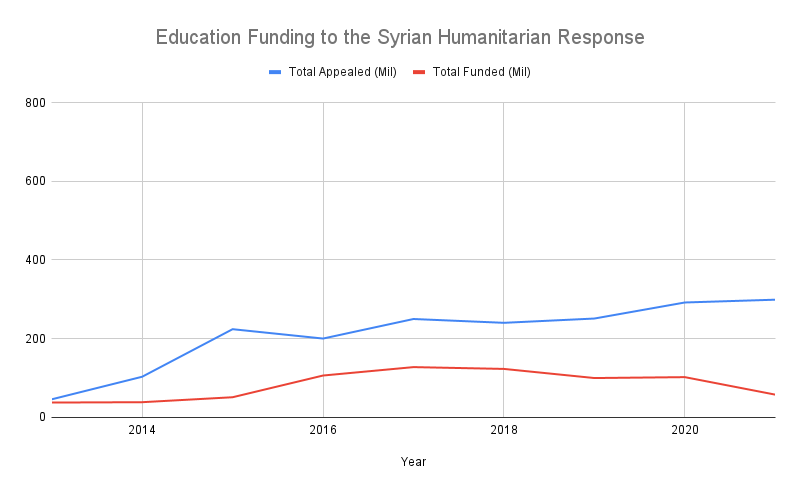

OCHA’s Financial Tracking System (FTS) provides the most reliable picture of funding for education and allied sectors across the humanitarian response in Syria. However, FTS data is still limited, since it is dependent on individual reporting by agencies that receive funding.83 According to the FTS, the Syria Humanitarian Response Plan for Education has never been more than 55% funded, except in 2013, when needs were not nearly as extreme as they are today. Since 2013, over $740 million has been spent on education in Syria, according to the FTS (although actual figures could be much higher84). However, it has mostly come in the form of short-term funding.85 This disincentivizes investment in quality components of education, encouraging disproportionate focus on the “hardware” of education, such as school equipment, teacher incentives, and school supply distribution. This leads to a de-prioritization of quality components of education programming such as monitoring of progress of holistic86 learning outcomes87 in a standardized manner by geographic hub, at a minimum88 because such interventions take time, skills, and investment.

According to OCHA, a mere $60 million was allocated to the education sector in 2021 — only 19% of the nearly $300 million appeal and just 4% of the year’s total humanitarian funds. Even when shorter-term funds are dispersed, the volatility of the context continues to make it susceptible to suspensions or modifications with short notice.

Figure 2. Syria Humanitarian Response

Aid workers interviewed for this analysis consistently reported that the failure of donors to commit to predictable, multi-year funding — despite the fact that the Syrian conflict has been going on for more than a decade — is one of the biggest challenges they face. This is also contradictory to the requests to articulate a strategy to combat armed influence on children and communities in Syria, to which education is crucial.89 With limited resources all around, aid workers revealed the unfortunate waste that results from short-term partnerships and intermittent funding.90 Additionally, aid workers emphasized donor fatigue in funding nearly-identical yearly response plans in nearly every sector.91

The Challenge of Data Management and Disaggregation per Region

Data in the Syria response is not disaggregated by hub or geographical region, demonstrating a challenge with data integrity across Syria, both within and beyond the education response. Published data across the WoS is not regularly updated and suffers from issues of insufficient, poor quality, and inconsistent data.92 Aid workers interviewed for this report expressed skepticism regarding the capacity of the WoS platform and individual hubs to collect and share accurate data.93 Although a WoS mechanism was established to facilitate better coordination across the different hubs, including in terms of information management, this has not yielded robust results in terms of data and data analysis within the education sector. Beyond the limitations in sufficient resources and capacity for WoS data management, the enduring geographic divides that have become entrenched by years of armed conflict continue to inhibit a more harmonious and standardized humanitarian response across Syria.

Failure to Prioritize Education in Syria Will Continue to Have Devastating Consequences

Inaction or continued short-term action in Syria that fails to adopt an early recovery framework will reinforce a cycle of dropout, poor attendance, and poor teaching and learning within a context that is exceedingly dangerous to children and youth. Education often acts as a safety net for children, and the link between access to school and child protection concerns has been well documented throughout the Syria crisis. The country also faces a worsening economic crisis, with the currency plummeting to record lows, while the cost of food and other essential goods has skyrocketed. As a result, more than three-fourths of households indicated an inability to meet basic needs in 2021.94 It is tragically no surprise that close to one-third of households report at least one child needing to work to support the household as a reason for not attending school.95

Moreover, 71% of communities mention that child marriage is an issue for adolescent girls. Once trapped in child marriages, it becomes difficult to reverse the effects and facilitate a return to school for these adolescent girls.96 Global research consistently points to the fact that keeping girls in school is one of the best ways to prevent child marriage, with the likelihood of marriage decreasing by six percentage points each additional year a girl remains in secondary education.97 Therefore, getting children engaged in learning, maintaining their access to education, and improving holistic learning outcomes through that access all deserve attention. Continuity of learning is also dependent on the quality and quantity of education personnel. Learning cannot continue as teachers remain unpaid or under-paid, which severely impacts their own livelihoods and well-being and pushes them to pursue other work. Additionally, personnel training that is not standardized and continuous, to meet demands of multi-level and overcrowded classrooms, will not yield quality results.

Beyond violating the fundamental rights of children in the short term and subjecting them to various forms of violence, continued disruptions to education in Syria will have devastating long-term effects. The overarching loss will entail children and youth’s decreased capacity to contribute to society and the future Syrian economy, which cannot thrive if aid dependency persists indefinitely. Education is foundational to economic growth and poverty reduction.98 Unless serious action is taken to bring youth up to speed with minimum global learning standards, aid dependency will increase, both for current and future generations, and their ability to contribute to the eventual rebuilding of their country will be severely diminished. The devastation to Syria’s physical infrastructure and human capital after a decade of war suggests that the failure to mobilize future generations in its eventual reconstruction could subject the country to a perpetual state of instability and underdevelopment. Moreover, action is urgent because there is a critical window of time to return children and youth aged 10 to 18 to structured learning of some sort that, if passed, severely diminishes the likelihood they will ever go back.

Donors have a unique responsibility to act for several reasons. Funds dispersed should be better accounted for, and that accountability requires better oversight of agencies and donors that have the resources to deliver higher quality outcomes — in particular, U.N. agencies and international NGOs. Aid workers interviewed for this report emphasized the scrutiny local organizations face and their experience bearing the brunt of overcompliance, while international agencies do not receive the same scrutiny.99 It is critical that those receiving funds are held equally accountable across the board.100 Accountability and oversight matter at all levels and donor behavior should reflect this.

Donors possess serious potential to drive the response in a more sustainable direction by both increasing the amount and predictability of funding and more effectively leveraging their influence to improve the quality of programming, subsequently shaping outcomes in education. Donors can incentivize efficiency of funds, higher quality training of teachers with support of education authorities, improved monitoring of student retention and dropout, as well as several other key activities, which can provide a more nuanced picture of education in Syria and a clearer plan of action. Key donors working directly with the Syrian MoE and de facto education authorities in areas outside of government control can also incentivize standardization across territories if they improve coordination at the donor level. What is crucial is harmonization among key donors first and utilizing two key channels to maximize reach to all education implementers, whether they have bilateral arrangements with those agencies or not. These two channels are: 1) The education cluster at the WoS level and in each territory mentioned; and 2) NGO forums and platforms that allow for implementing agencies — both international NGOs and their local NGO partners — to be further reached.101

Recommendations to Donors for Education Coordination and Funding

-

Prioritize education in discussions of Syria’s stability and long-term prospects of recovery. Oftentimes, discussions revolving around Syria’s prospects for long-term recovery focus on conflict dynamics, economic stability, the political environment, governance, and health infrastructure, among other factors. More serious efforts must be undertaken to discuss the role of a strengthened and adaptable education system that can respond to the needs of future generations of Syrians. Rhetoric shapes reality and education must be considered as seriously as other factors.

-

Increase predictable and flexible multi-year funding for education in Syria. Donors must increase multi-year funds for education in Syria,102 coordinating to improve funding coverage at all levels (i.e. early childhood, primary, and secondary education) to avoid saturation in one level or geographic hub, while neglecting others. Short-term investments can do more harm than good due to the destabilizing effects of disruptions to programming when funds are not renewed.

-

Facilitate development of a common framework for early recovery for education in Syria through relevant fora. Key donors should facilitate the process of developing a common framework for what early recover entails in the education sector in Syria, from defining objectives to specifying activities,103 through the WoS mechanism and NGO forums. Coordination with the existing Early Recovery and Livelihoods Cluster should be undertaken; however, the WoS Education Cluster, the GoS MoE, and relevant de facto authorities are ultimately responsible for determining how to apply an early recovery approach to education in Syria. A framework that defines early recovery in the context of the protracted crisis is required for a coherent and sustainable response after more than a decade of conflict. This can be done without crossing the political redlines linked to economic sanctions and reconstruction funding, which differs from early recovery programming.104 In the absence of such a coordinated effort, as is the case currently, donors can play a key role in encouraging U.N. and NGO partners to initiate and complete this process.

-

Make funding to education providers conditional on adherence to the early recovery framework. Once a clear early recovery approach to education programming in Syria is defined and adopted at the WoS level, donors’ appraisal of proposals and distribution of funding (including pooled funds and bilateral funding) to education actors should be made contingent upon adherence to early recovery principles and capacity to advance early recovery objectives.

-

Leverage donor relationships with the Syrian MoE and other de facto authorities to enhance system-wide continuous105 capacity strengthening. All donor countries that have leverage with the MoE in Syria, the country’s only internationally-recognized education authority, must encourage stronger accountability by authorities for funds granted, such as for education system strengthening and higher incentives106 for education personnel. The MoE and de facto authorities in other areas should be engaged to take responsibility for teacher salaries where resources are available and engage in systematic, standardized capacity building and training of teachers.

-

Leverage relationships at all levels (e.g. diplomatic, donor agencies, U.N. agencies, NGOs) with the MoE and all relevant authorities to facilitate safe and consistent access for children and youth in GoS-held territories to sit for national exams.107 This can include direct funding of the process or ensuring non-discrimination and safe access for male and female students to take national exams when living in non-GoS held territories of Syria.108 Authorities from all areas of the country must be engaged by donors, U.N. agencies, and NGOs to facilitate transport of students and ensure safety, regardless of the student’s background, community, and residence.

-

Maintain direct engagement with NGO forums to strengthen reporting, coordination, and bilateral funding.109To complement the WoS coordination mechanism (e.g. clusters, sectors, working groups) but ensure representation and input of international and local NGOs,110 which are the primary implementers of programming in Syria, NGO fora should continue to be engaged directly by donors at the geographic hub level.111

-

Improve and expand humanitarian exemptions from sanctions for all legitimate aid operations, including education interventions. The U.S. government and European countries leveraging sanctions on Syria must continue exploring ways to mitigate the unintended effects of sanctions on humanitarian operations, including through improvements in provision and communication to all relevant parties of humanitarian exceptions. Sanctions must not impact youth education programs in GoS-held parts of Syria.

Technical Education Recommendations to Donors

-

Engage in genuine investment in capacities of education personnel. Engage national and de facto authorities to sustainably ensure coverage of teacher salaries. Teacher turnover and performance will improve with system-wide skill-building and monetary incentives.112 Current subsidization of salaries through humanitarian funds is unsustainable; authorities must understand that they are ultimately responsible for paying teachers and maintaining education access. Authorities can be supported to develop a salary scale and capacity building strategy for teachers.

-

Incentivize standardized approach to monitoring progress of holistic learning outcomes at the geographic level. Donor agencies must incentivize with some type of standardized assessment of progress with learning outcomes in education activities they fund. This can be done through the WoS Clusters/Sectors and Education Working Groups.113 Measurement of learning progress is a weakness of Syria’s education sector, which undermines donors’ visibility of programming impact and efficient use of funds for education.114

-

Invest in technical education materials developed at the interagency level.115With nearly a billion dollars spent on education in Syria, few materials used with teachers and learners have been standardized. Donors should invest funds and encourage relevant technical fora at the global level and within Syria to harmonize education training materials, as well as skills programs for children and youth.116 All Arabic materials can be used at the regional level, making them also an investment for donors in other responses they fund.

-

Provide funding for economic support to households to encourage school attendance in line with integrated criteria. Economic barriers are the largest obstacles to education.117 A framework and guidance has been developed for use of cash assistance in education to offset the direct and indirect cost of schooling.118 In Syria, UNICEF has implemented cash assistance for families of children attending school.119 Success with Syrian refugees has been reported nearby in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Education providers should engage with existing cash providers to utilize economic support for families as a way to minimize negative coping mechanisms, such as child labor, and improve school attendance.120

-

Develop strong evidence base on the link between education and armed recruitment. The link between education and recruitment into armed groups has long been used to justify action, despite being based largely on anecdotal evidence (unlike child labor and child marriage, which have an extensively documented tie to school attendance.)121 Donors should consider funding specialized research, with Syrians in the country and across the region, to be conducted by contextually aware and linguistically-skilled, independent experts.122 Nearly a decade of evidence on the subject matter exists across the region, as well as in Syria, and it should be harnessed sensitively to better understand the role education can play in resilient post-conflict communities.

About the Authors

Kinana Qaddour is an education specialist and education in emergencies practitioner. She has previously worked in the Syrian humanitarian response as well as the Rohingya refugee and Yemen education in emergency responses.

Salman Husain is a humanitarian practitioner focused on conflict, displacement, and protection issues in the Middle East. He has worked with international NGOs on the regional Syrian humanitarian response. The views expressed in this paper are their own.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all humanitarian staff, in particular Syrian staff, who participated in the interviews and supported us with our findings, as well as all education personnel in Syria working to ensure the country’s crisis-affected children have access to quality education.

Endnotes

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic” (UN OCHA, February 22, 2022), https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/hno_2022_final_version_210222-2.pdf.

- UNICEF, “Whole of Syria Humanitarian Situation Report: End of Year 2021” (UNICEF, February 9, 2022), https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF%20Whole%20of%20Syria%20Humanitarian%20Situation%20Report%20-%20January%20-%20December%202021.pdf.

- Out of school children (OOSC) and youth are defined as those who do not participate in any type of structured learning (formal or non-formal education).

- Concentrated in the northwest and northeast provinces, for children ages 11 and up. UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD), “SDG 4 Quality Education: 2021 Report,” 2021, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/goal-04/.

- Save the Children UK, “Futures Under Threat: The Impact of the Education Crisis on Syria’s Children” (Save the Children UK, 2014), https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/futures_under_threat1.pdf/.

- UNICEF et al., “Syria Crisis: Education Interrupted Global Action to Rescue the Schooling of a Generation,” December 2013, https://www.worldvision.org/wp-content/uploads/Syria-Crisis_Education-Interrupted_Dec-2013.pdf.

- UN OCHA defines early recovery as “an approach that addresses recovery needs that arise during the humanitarian phase of an emergency; using humanitarian mechanisms that align with development principles. It enables people to use the benefits of humanitarian action to seize development opportunities, build resilience, and establish a sustainable process of recovery from crisis.” UN OCHA, “Early Recovery,” Humanitarian Response, accessed March 3, 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/clusters/early-recovery.

- UNICEF, “Education in Emergencies,” UNICEF, Accessed March 3, 2022. https://www.unicef.org/education/emergencies.

- United Nations, “Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond,” August 2020, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond.

- Rebecca Winthrop, “COVID-19 and School Closures: What Can Countries Learn from Past Emergencies?” (Brookings Institution Center for Universal Education, March 31, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/research/covid-19-and-school-closures-what-can-countries-learn-from-past-emergencies/.

- INEE, “INEE Minimum Standards for Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery” (Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies, December 3, 2010), https://inee.org/resources/inee-minimum-standards.

- UN OCHA, “What is the Cluster Approach?,” Humanitarian Response, accessed March 3, 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/coordination/clusters/what-cluster-approach.

- Marian Hodgkin and Allison Anderson, “The Creation and Development of the Global IASC Education Cluster” (Education for All Global Monitoring Report, 2010), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191224.

- Jahal Rabesahala de Meritens et al., “Guidance Note on Inter-Cluster Early Recovery” (Global Cluster for Early Recovery (GCER), January 2016).

- Ibid.

- UNICEF, “Humanitarian Action for Children Appeal” (UNICEF, 2022), https://www.unicef.org/appeals.

- In this report and based on its use by interviewees, formal education refers to learning with the current GoS curriculum.

- Non-formal learning opportunities aim to provide opportunities for catch-up and accelerated learning, for students to either to re-enter formal schooling or develop skills and competencies for those not likely to re-enter formal schooling.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Based on existing public reports and KIIs with individuals working in all geographic hubs of Syria.

- Used differently by interviews and in various reports reviewed on the education situation in Syria.

- The curriculum known as the “SIG Curriculum’’ is a revised version of the GoS curriculum after it was edited and contentious material and politicized content removed. Interview of NGO staff in NWS, Feb. 2022.

- The SLP, developed pre-conflict, and revised in 2016 by UNICEF, UNRWA, and the Syrian MoE in 2016.

- On a limited scale, in NWS. Interviews with NWS education response staff, Feb. 2022.

- Curriculum B is recognized by the GoS MoE as an accelerated curriculum if taught in their territory; one semester is equivalent to one academic year. Interview of Damascus-based NGO staff, March 2022.

- Taught in formal schools in GoS-territory. Interview of Damascus-based NGO staff, March 2022.

- Interview of individual aware of humanitarian situation in NES, Feb 22, 2022.

- Based on interviews and published reports on education in Syria, which may not provide complete picture of curricula and learning packages used.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Estimate by UN OCHA.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid. Includes verified figure only; actual figure may be higher.

- UNICEF, 2021.

- The majority of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in and outside of formal camps are children and youth (age 0-17), who experience higher rates of distress and poor protection outcomes. UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- UNICEF, “Whole of Syria Humanitarian Situation Report.”

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid. Children travel up to 45 minutes to school in Idlib. Long, unsafe school journeys are also reported in Damascus and Rural Damascus.

- Ibid.

- Based on interviews and mappings of regions by humanitarian hub.

- See Figure 1.

- Syrian Arab Republic: Dara’a Flash Update 2, Hostilities in Dara’a Governorate, (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Aug 2021), https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-dara-flash-update-2-hostilities-dara-governorate-12.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Interview of individual working in Damascus-based education response, March 1, 2022; Ibid.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NES response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Interviews of individuals aware of the education situation in GoS-held territory, March 2022.

- Interview of an individual who works in NWS response, Feb. 2022.

- UNICEF, “After almost ten years of war in Syria, more than half of children continue to be deprived of education,” press release, Jan. 24, 2021, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/after-almost-ten-years-war-syria-more-half-children-continue-be-deprived-education.

- The six grave violations are: Killing and maiming of children; recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups; sexual violence against children; attacks against schools or hospitals; abduction of children; and denial of humanitarian access for children.

- Northwest Syria Education Cluster/Cross-Border response.

- “Humanitarian Response Plan: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid. Per the 2022 Humanitarian Needs Overview for the Syrian Arab Republic, economic barriers are the most prominent cause of OOSC’s status.

- Teacher salaries, when paid, have been reported to be between $100 to $300 a month and there have been harmonized salary scales developed in NWS throughout the response, but application has been a challenge. Interview of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- Northwest Syria Education Cluster, “North West Syria: Teachers on strike as one in three teachers working without pay,” press release, March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/north-west-syria-teac….

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NWS response, Feb. 14, 2022.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NWS education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- Interviews of individuals working in NWS response, Feb. 2022.

- Interviews of individuals working in NWS response, Feb. 2022.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NWS education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- See Figure 2.

- Jane Arraf, “Violence Erupts at Syrian Camps for ISIS Families, Leaving One Child Dead,” New York Times, Feb. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/09/world/middleeast/syria-camp-violence.html.

- Because vast areas within the NES have been under the control of Kurdish and other non-government forces since the onset of the war, a cross-border operation was initialized in 2014 through a resolution passed by U.N. Security Council to enable service delivery by aid organizations from neighboring Iraq. However, Russia and China have progressively closed down three of the four initial border crossings, rendering the NES without any official cross-border mechanism backed by the U.N. and therefore devoid of an official U.N. presence. Cross-border operations continue through international and local aid organizations, but they lack the multimillion dollar funding and vast resources enabled through the U.N. system.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NES response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Interview of an individual who works in the NES education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- Interview of an individual who works in the NES education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- “Humanitarian Response Plan: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Interview of an individual who is familiar with the situation in NES, Feb. 22, 2022.

- Global Partnership for Education, “Reaching Syria’s Underserved Children: Multi-Year Resilience Education Programme (MYRP) Syria 2020 – 2023,” (Global Partnership for Education, Jan. 2020), https://www.globalpartnership.org/sites/default/files/document/file/2020-01-syria-multi-year-resilience-education-program.pdf.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the NES response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Sardar Drwish, “The Kurdish School Curriculum: A Step Towards Self-Rule?” (The Atlantic Council, Feb. 2017), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/the-kurdish-school-curriculum-in-syria-a-step-towards-self-rule/.

- Interview of an individual who works in the NES education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- Interview of individuals working in NWS response, Feb 2022.

- Christopher Talbot, ”Education in Conflict Emergencies, in light of the post-2015 MDGs and the EFA Agendas,” UNESCO IIEP, https://docs.iiep.unesco.org/E032340.pdf.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the Syrian humanitarian response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Interviews of individuals familiar with NWS education response, Feb. 2022.

- Interviews of individuals who have worked in the Syrian humanitarian response, Feb. 2022.

- Discussions have taken place for potential multi-year, rather than single-year, humanitarian response planning in Syria. Interview with NWS NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- FTS does not provide a breakdown of where funding is channeled. This makes it difficult to analyze proportionality to needs and equitable distribution based on people in need and targeted. Interviews of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- FTS does not provide the most accurate funding picture. Interview of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- Multi-year funding is limited for education interventions. Interviews of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- “Holistic” learning outcomes refer to outcomes linked with literacy, numeracy, and psychosocial skills.

- All geographic hubs expressed interest in and efforts to standardize assessment of holistic learning outcomes. However, none shared standardized efforts by geographic hub, but rather by individual agency.

- No standardized effort by geographic hub or cluster/working group. Interview of NGO education staff, Feb. and March 2022.

- Interview of individuals working in the Syrian humanitarian response, Feb. 2022.

- Interview of individuals who have worked in the NWS education response, Feb. 11, 2022.

- Interview of individuals working in the NWS, Feb. 8, 2022.

- Interviews across all geographic hubs shared the challenge of contradictory data and figures included in the WoS cluster reports as well as at the hub level. Interviews of NGO staff, Feb. and March 2022.

- Salman Husain and Yasmine Chawaf, “Syrian lives in Peril: The Fight to Preserve Syrian’s Last Humanitarian Border Crossing,” (The Atlantic Council, June 2021), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Syrian-Lives-in-Peril-The-Fight-to-Preserve-Syrias-Last-Humanitarian-Border-Crossing.pdf.

- UN OCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Ibid.

- Resulting from social stigma of married girls attending school. Ibid.

- “Child Marriage and Education,” (Girls Not Brides, March 2022), https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/learning-resources/child-marriage-and-education/.

- “Learning out of Poverty,” (USAID, July 2015), https://www.usaid.gov/infographics/50th/learning-out-of-poverty.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the Syrian humanitarian response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Interview of an individual who has worked in the Syrian humanitarian response, Feb. 6, 2022.

- Interviewees raised issues with representation in the cluster system. Utilizing both clusters and NGO forums allows for greater representation, especially for Syrian NGOs. Interview of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- There are currently limited multi-year funding programs for education. Interviews of NGO staff in NWS and NES, Feb. 2022.

- Partial or full rehabilitation of learning facilities is a top priority in all areas. Interviews of NGO staff in all geographic hubs of Syria, Feb. and March 2022.

- The United States Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has expanded permission for specific activities that are exempted under sanctions if implemented by humanitarian actors in Syria to include those which would support early recovery, such as rehabilitation of local schools.

- This means training throughout the year rather than only at the beginning of the academic year or during the summer months (also known as in-service training).

- Incentives can only be covered in the short term, or intermittently, by humanitarian and development actors. Education authorities should be further incentivized to prioritize this activity. Interview of NGO staff, Feb. 14, 2022.

- Exams taken in areas outside of GoS-held territory are not recognized in other territories, nationally, or internationally; therefore, access to certified and recognized learning can only be through the GoS MoE and its exams offered in their facilities in areas under their jurisdiction.

- The GoS MoE has also facilitated access to national exams for refugees in nearby Jordan and Lebanon as well as those in Syria. Interview of NGO staff, March 2022.

- Interviews of individuals working in both NWS and NES shared improved bilateral engagement with high-level donors to redistribute, revise funding decisions and programming. Interviews of individuals working in NWS and NES.

- NGOs face challenges in reflection and representation in the U.N-led Cluster system, as they are the primary implementers. Interview of NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- This has been done in both NWS and NES to some success in planning redistribution of aid based on immediate need. Interview of NGO staff in NWS and NES, Feb. 2022.

- Interviews of NGO staff in NWS, Feb. 2022.

- Capacity building should be sector-wide to maximize impact.

- All three geographical regions shared the challenge of harmonized tools to assess holistic learning progress, particularly in non-formal education programs (learning outcomes as well as psychosocial and other non-cognitive skills.)

- The inter-agency network for education in emergencies (INEE), a global, neutral network that supports education in crisis contexts, convenes U.N. agencies, donors, and international and local organizations. The network is often commissioned to develop open-source inter-agency materials in English, Arabic, French, Spanish, and Portuguese for use globally.

- The Teachers in Crisis Context (TiCC) training pack is an example of widely used guidance developed at the inter-agency level facilitated by INEE.

- “Humanitarian Needs Overview, Syrian Arab Republic.”

- See Global Education Cluster (GEC) analysis and guidance on cash incentives in education programming.

- UNICEF, “Whole of Syria Situation Report,” (UNICEF, October 2021), https://www.unicef.org/media/112666/file/WOS-Humanitarian-SitRep-October-2021.pdf.

- Donors can support with incentivizing development of harmonized criteria for use in all parts of Syria.

- Suggested need for stronger evidence-based research on the topic. Interview with NGO staff, Feb. 2022.

- This ensures the research is independent and not used as a document to advocate for funding in a specific sector. Relying on anecdotal, incomplete, or unverified evidence to justify education programming, although done with good intentions, can do harm to communities.

Photos

- Cover photo: Students start school in Afes on Sept. 20, 2021 at the beginning of the school year in Idlib Governorate, despite the poor conditions due to an air raid that hit and partially destroyed the school in 2019. Photo by Anas Alkharboutli/picture alliance via Getty Images.

- Contents photo: Syrian pupils take their seats in class in the capital Damascus on Sept. 13, 2020, during the first day of the school year. Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/AFP via Getty Images.

- Children are seen in a classroom in Hasakah Province in northeastern Syria on Nov. 19, 2020. Photo by Xinhua/Stringer via Getty Images.