Temporary marriages and sex tourism in Iran

Sex tourism and sex trafficking in Iran are increasing. One contributing cause is the practice of sigheh. Sigheh (also known by its Arabic name “nikah mut‘ah”) allows men to marry a woman for a pre-determined period of time, have intimate relations with her, and then leave her without consequences. While sigheh is often justified using moral terms, in practice it is a legal loophole for prostitution. The problems associated with sigheh are rampant, but there is almost no research or data about this legalized form of sexual exploitation and about the lives of its victims in Iran.

“Chastity” is the principle most commonly invoked to justify sigheh. The Supreme Council for the Cultural Revolution defined its conception of chastity in an article published on its website: “Chastity helps men to prevent lust…Chastity is internal and prevents external behaviors such as illegitimate relationships, illegitimate children, abortion, and street harassment…In fact, observing boundaries in human relationships is called chastity, so that individual feelings and desires, both sexual and non-sexual, do not transcend the boundaries of morality and justice.”

Some proponents of sigheh argue that the practice encourages chastity because it ensures that sexual relations occur within the confines of marriage. Another argument is that many men have no other possible source for sexual companionship other than through a paid arrangement. This includes single men, men who travel for extended periods, and those whose wives have long-term illnesses.

Sigheh: A religiously sanctioned legalization of prostitution

Sigheh is legal according to Iranian Civil Law article 1075. Men/boys aged 15 and older and women/girls aged 13 and older can enter into such a relationship. Usually, according to Iranian tradition, virgin girls must obtain permission from their father to marry permanently or temporarily, but according to the Iranian Civil Law Articles 1043 and 1044, girls can obtain permission to become a sigheh wife by simply identifying their husband-to-be by name and providing details about their relationship such asthe value of the mehrieh (dowry) and proposed length of the marriage.

A sigheh can last for one hour, a few days, a few months or longer. The couple can sever this relationship without a legal divorce according to Iranian Civil Law Article 1113.A contract for a sigheh does not make the man responsible for financially supporting the woman. She has no right to inheritance or similar rights that women have in a permanent marriage.

Religious justifications for sigheh are common. One website cited at least 15 hadiths (sayings of the prophet) as evidence of the benefits of sigheh for men, even if they are already married. According to his interpretation of the cited Hadiths, sigheh purifies men of their sins and makes paradise their reward

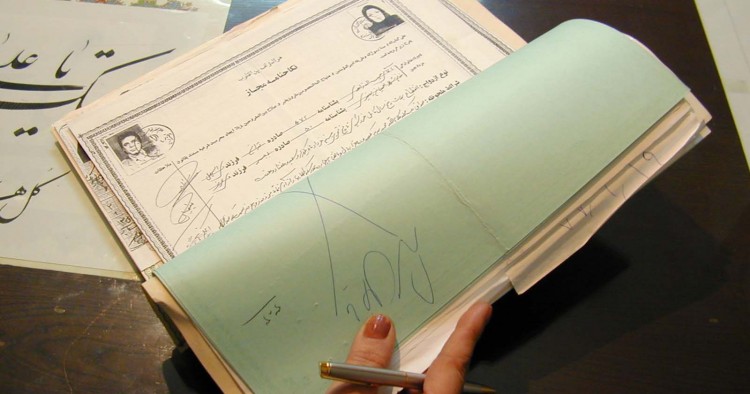

To form a sigheh in Iran, a man and a woman must enter into a verbal contract by reciting an Arabic formula that specifies the value of the dowry and the length of the marriage. Before the Islamic Revolution and for many years after, these rites were performed in a mosque by clergy. For the last few years, however, the need for clergy has been obviated by the availability of documentation online.If a man wishes to reserve a hotel room with his temporary wife, he has to show proof of their relationship. Not all hotels in Iran allow men to stay with their sigheh wives.

A hotel reservation…with a sigheh wife

With a population of 3 million, Mashhad is Iran’s second largest city. Largely due to its Shi‘a pilgrimage sites, the city attracts about 25 million foreign and domestic tourists each year. Unfortunately, the city also attracts men in search of sighehs, and not even COVID-19 has put an end to this practice.

For men seeking a sigheh, the first step is choosing a wife. This can be done online through one of several matching sites. There are several websites in Iran for “matching” men with sigheh spouses. Colonel Ali Niknafas, of the Iranian Cyber Police (FATA), in an interview posted on FATA’s official website that “there are many websites that provide facilities for ‘matching.’ They provide services without getting permission for their business, although there are legal websites that provide ‘matching’ and the paperwork.” Matching websites also send out text messages with lists of women and descriptions of their age, weight, color of their eyes, hair, and other attributes. In Mashhad, men can even arrange a sigheh with certain hotel reservations.

I contacted a life-long resident of Mashhad named Fatti through her family members. She herself has never been a sigheh wife, but she was able to speak on the subject, having heard stories from a university classmate: “During their trip to Mashad, men can request to stay at the hotel with their sighehs for one hour or more. Before arrival, the customer needs to purchase legal documentation of the sigheh. Almost the whole process can be done through the internet or SMS. The customer finds the women from the web site, although he has access to the albums of women at the hotels too.” She talks about sigheh with feelings of shame, sorrow, and hate. Fatti herself has two bachelor degrees — one in finance and one in marketing — yet she cannot find a job. She has considered leaving Iran because “there is no hope for a good life in Iran,” but she does not know where she could go. At the same time, she feels responsible for her parents and her younger siblings. “Most people are waiting…I don’t know what to do” she said with pain.

U.S. reaction to Iran’s sex trafficking

According to a report from the U.S. Department of State, “the Government of Iran does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so.” In 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton downgraded Iran from Tier 2 to Tier 3 in the Department of State’s annual report on human trafficking, indicating that Iran was making no significant effort to combat the problem. Despite the fact that prostitution is illegal, one study estimated that there are approximately 230,000 female sex workers in Iranian urban settings. The demand for commercial sex is most prevalent in large urban centers, including the major pilgrimage sites of Qom and Mashhad. It is believed that traffickers may exploit children as young as 10.

Poverty and a worsening economy are pushing Iranian women into prostitution. An estimated 50 percent of female sex workers in Iran are married women. Traffickers often force these women into remaining prostitutes, making them vulnerable to execution for adultery. It is reported that Iranian, Iraqi, Saudi, Bahraini, and Lebanese women in these locations are highly vulnerable to trafficking.

The “danger” of women’s hair versus the “safety” of sigheh

The website of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution states, “Chastity and [wearing the] hijab are intertwined and each is a prerequisite for the other. With planning by the government to create a culture of modesty, a clean society can be achieved.” Thus, the principle of chastity can be used to justify legalized prostitution as well as modesty in women’s attire.

Thousands of women are forced to wear the hijab against their will. We know that hundreds of women have been arrested and many are in prison for not wearing their hijab or wearing it “incorrectly.” According to Iranian Civil Law, Article 638, a woman can be sentenced to prison for 10 days to two months or have to pay a fine merely for being seen in public with “bad hijab” (visible strands of hair, prohibited cloth design or color, etc.).

A higher penalty is reserved for women who wear no hijab in public. According to Iranian Civil Law, Article 134, their sentence is 15 years in prison. One 22-year-old Iranian woman named Saba Kurde Afshari was arrested and sentenced to prison for 24 years for not wearing her hijab while on a sidewalk.

The irony is that many who claim to defend the honor and modesty of women by imposing the hijab also celebrate sigheh for “preventing prostitution” and creating a “safe” community. Women in Iran are not equal citizens in the streets and in the bedroom. It is time to stamp out gender-based discrimination and exploitation, especially when justified by religious principles.

Fariba Parsa is the founder and president of Women’s E-Learning in leadership (WELL) and a non-resident scholar with MEI's Iran program. The views expressed in this article are her own.

Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.