Since Russia’s September 2015 military entry into the Syrian conflict, the Assad regime has steadily regained the territory it lost throughout the country from rebel advances and tactical withdrawals. Although this advance has slowed since 2018, violence in the country continues unabated. This has particularly been the case in northwest Syria, where, aided by pro-government militias and Russian air power, Syrian government forces have clashed with an array of rebel and Islamist groups that are increasingly backed by Turkish military force. While violence and casualties spike during regime offensives, deadly munitions are launched almost daily, overwhelmingly by regime or Russian sources. This may seem like an obvious point for most observers of the war, but it is important to examine how these trends have played out over time.

First, by looking at the last three years, we can establish whether the fact that the Assad regime and Russia have carried out the overwhelming proportion of military actions in the northwest of Syria is a purposeful trend or a temporary blip. If purposeful, this would allow us to show how the Assad regime has used cease-fires as opportunities to consolidate its gains and reposition, doing so by heavily bombarding enemy-held areas to “soften” defenses and terrorize civilian populations into fleeing for the Turkish border. This, in turn, serves to undercut their commitment to the series of negotiated cease-fires. Finally, examining longitudinal data allows us to firmly dismiss a narrative of two equally matched sides in the conflict.

Methodology

For this study we employed ACLED’s Syria conflict database, which is considered to be the most comprehensive and widely used real-time conflict data available.[1] Data for Syria was downloaded for January 2017 through November 11, 2020, and the 12-month period from November 2019 to November 2020 was examined in closer detail, allowing for a comparison before and after the latest round of fighting in February.

Ground-based artillery and airstrikes were selected as the two event types that most clearly encompassed the one-sided violence that has been most prevalent in northwest Syria. Both airstrikes and artillery bombardments are designed to inflict pain and destruction at a distance with a low fear of immediate reprisal. The imprecise and destructive nature of these types of attacks also has a greater chance of creating collateral civilian damage and therefore speaks to the wider effects of sustained strategies of aggression by the Assad regime and its allies.

In order to focus the analysis on the primary vector in the conflict, between the Syrian government and rebel and Islamist forces and their respective foreign backers, a number of actors were excluded. Given its antithetical aims toward all other parties involved, ISIS was not included in the analysis. Similarly, the narrow aims of the U.S. military (counterterrorism) and Israel (anti-Iran) were also excluded as they are not a major factor along the Syrian government-rebel/Islamist conflict axis in the northwest. ACLED methodology also codes for “unidentified” military and armed actors, which were excluded since they could not confidently be ascribed to either the Syrian government or the rebel/Islamist alliance.

In a similar vein, we have collapsed the myriad individual armed groups, forces, and units involved in the conflict into four groupings to effectively examine the primary axis of conflict between the Syrian government, its allies, and the array of rebel and Islamist forces backed by Turkey. This, admittedly, flattens out some of the nuances of the conflict, such as being able to identify when Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) is responsible for an artillery attack versus the Syrian Arab Army and so on. For another point of caution, even with cross-sourcing, ACLED’s dataset is not always able to determine whether an airstrike was carried out by Syrian or Russian planes or both. However, in all of these cases, the vector of violence is still clear, and these broader groupings are still valuable categorizations for our level of analysis.

Analysis

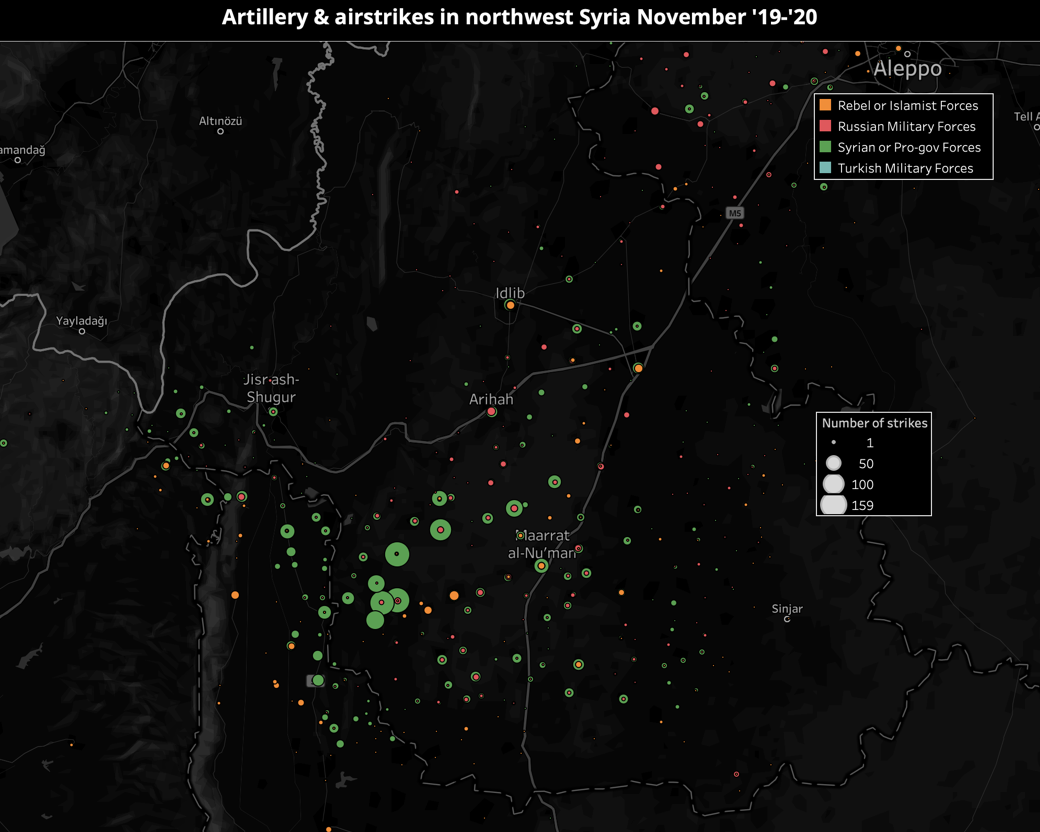

When looking at a map of all artillery and airstrikes in the period from November 2019 through November 2020, first, it is quite clear that the majority of attack are carried out by either Syrian, Russia, or pro-government forces across the northwest of the country, save for northern Aleppo, where the Turkish military is more active. Syrian government firepower is overwhelmingly directed at southwestern Idlib, with several towns being hit by at least 100 barrages in the 12-month period. Russian airstrikes — its ground artillery is rarely used — are spread more evenly across the whole of the northwest, although, as we will see below, they make up a significant portion of the overall number of attacks. Meanwhile, rebel or Islamist artillery strikes — we discount the possibility of airstrikes, given their lack of an air force — are also directed at the southwest of Idlib and northeast of Latakia Province, representing the frontlines of the fighting. For reference, the attacks coded to Idlib city represent ACLED’s methodology for coding of attacks that occurred within a province to the provincial capital by default when any further geographical determination was unavailable.

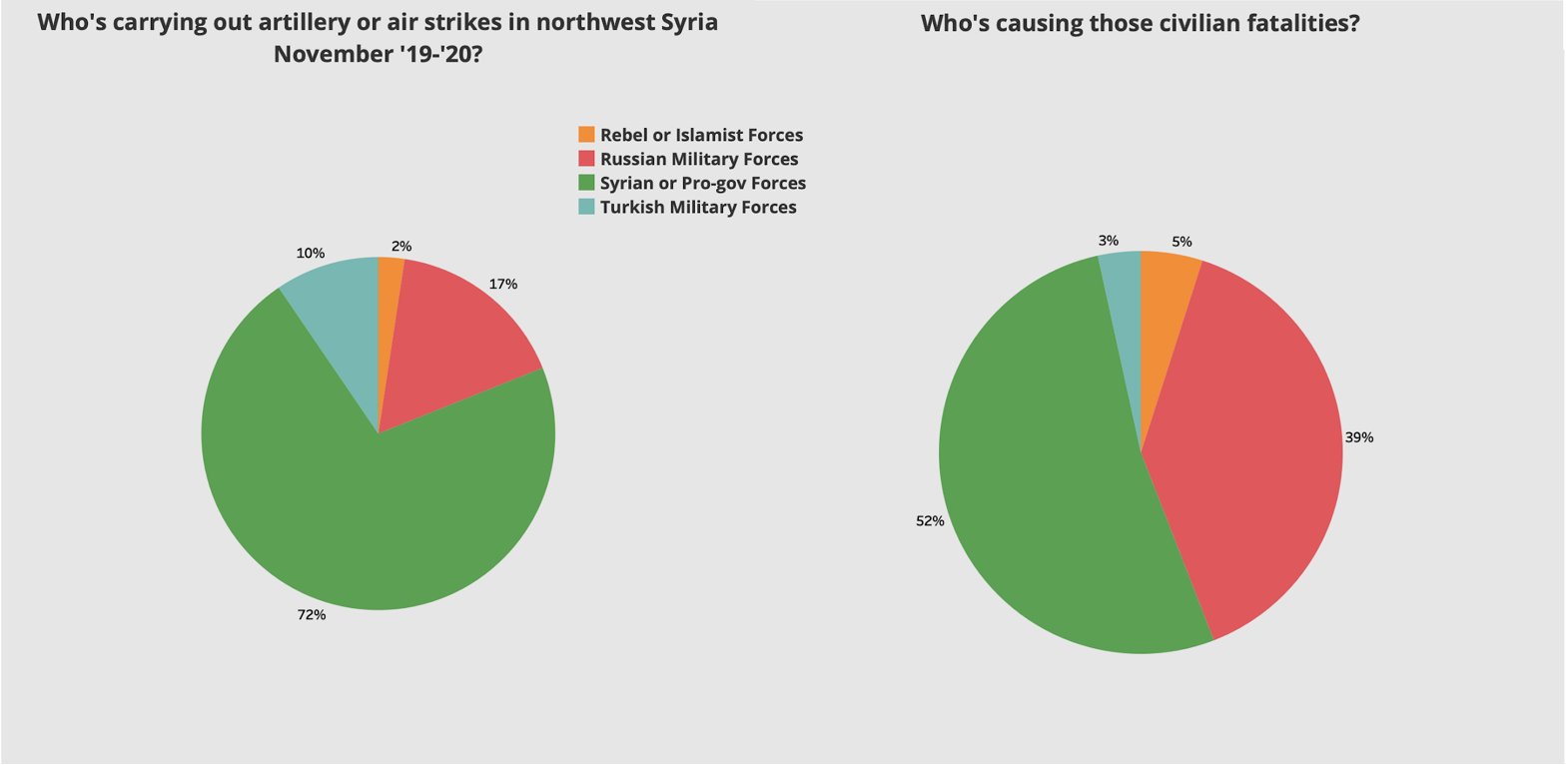

When aggregating the attack data, we find that the overwhelming number of attacks have been carried out by Syrian, pro-government, and/or Russian forces. In fact, nearly three-quarters of attacks were carried out by Syrian government or pro-government forces alone. Add in Russian airstrikes and we see that nearly 90 percent of attacks in the northwest are carried out by Syrian, pro-government, or Russian forces. The one-sided nature of artillery and airstrikes debunks the notion of a war fought between evenly matched sides and underscores the relentless violence of the Assad regime. Also of note is the higher proportion of civilian fatalities caused by Russian airstrikes (39 percent) in relation to the smaller overall percentage of attacks carried out by Russia (17 percent). We can draw at least two conclusions from this: First, Russian airstrikes are deadlier and cause significant civilian collateral damage, a

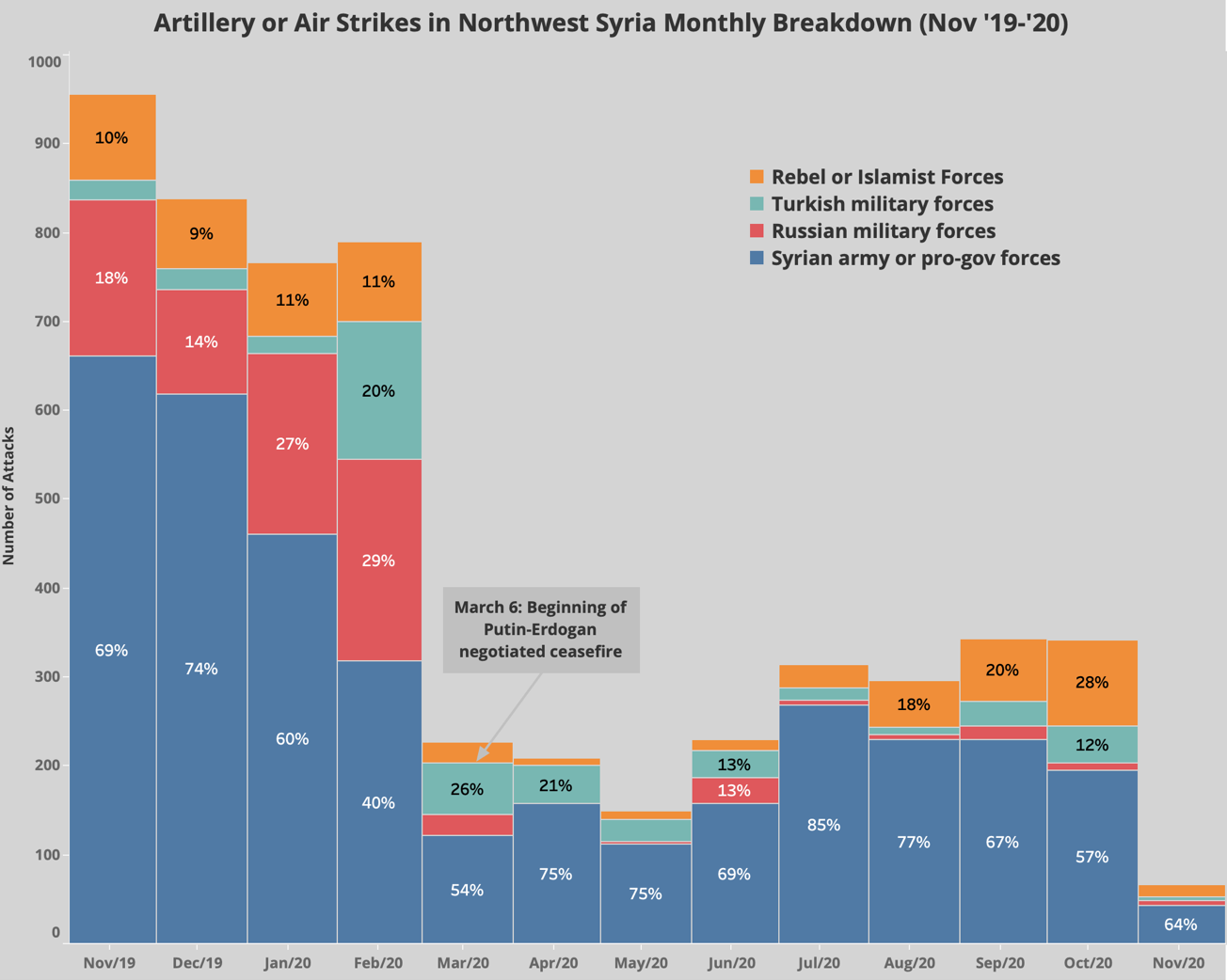

Looking at a breakdown of the artillery and airstrikes by month, a few trends are clear. First, Syrian or pro-government forces always make up a plurality of attacks and are the majority instigators, save for the latest round of fighting in February. Otherwise, Syrian and allied forces consistently account for the single biggest share of artillery and air attacks in the northwest of the country, month after month. Once again, this emphasizes the deliberate nature of the Syrian government’s strategy in relentlessly bombarding the northwest. Moreover, this strategy is once more highlighted by both the large scale of attacks in the leadup to the latest round of fighting (600+ attacks in November and December 2019) and the continuation of these attacks after the conclusion of the March 6th cease-fire. Though at a lower rate, government attacks are still outsized in terms of their proportion when compared to those carried out by rebel groups, Islamist groups, or the Turkish military.

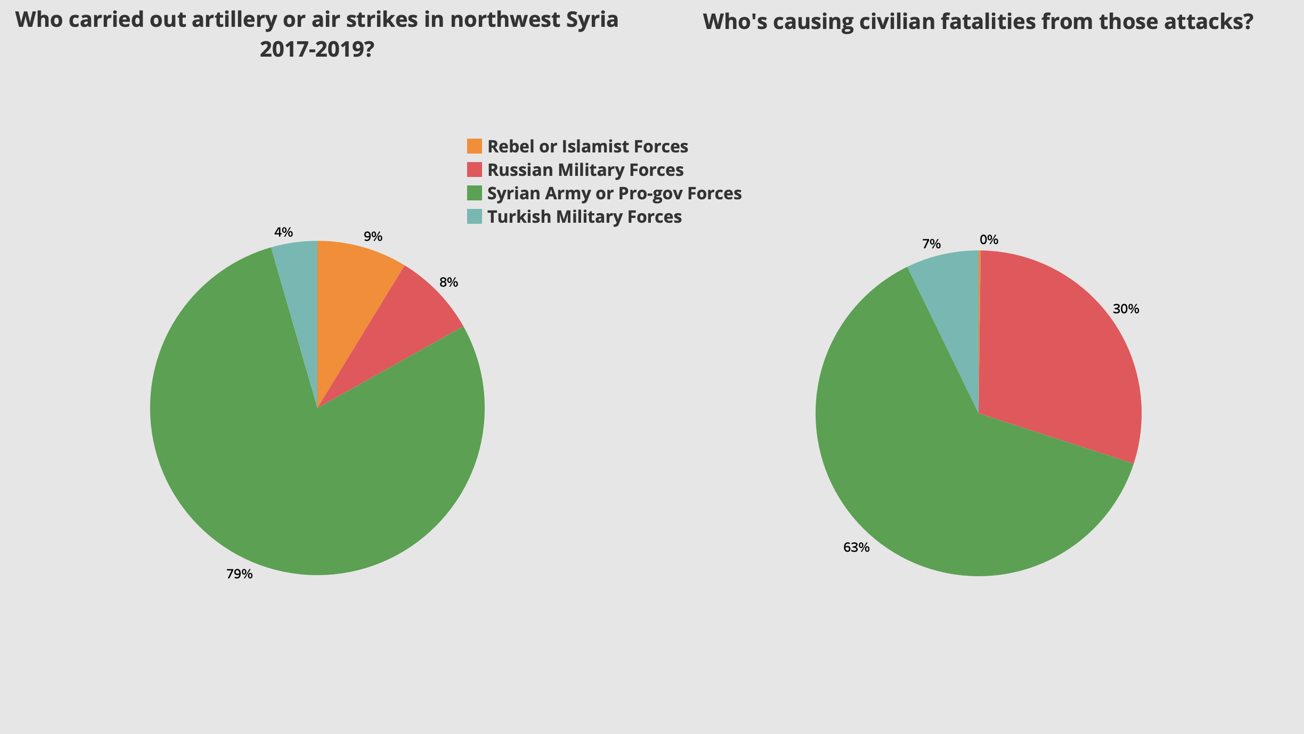

One final comparison underscores the long-term nature of the Assad regime’s strategy of persistent and overwhelming bombardments in the northwest. Even when looking at the period between 2017 and 2019, Syrian army or pro-government attacks still make up roughly three-quarters of attacks carried out, while Russian air power still accounts for a disproportionate number of civilian deaths compared to the overall number of attacks. Importantly, the percentage of civilian fatalities attributed to rebel or Islamist attacks in the area is almost zero (due to rounding). One reason for this is that these artillery and rocket attacks tend to be aimed southward at areas recently captured by regime forces that have been effectively depopulated.

Conclusion

An analysis of ACLED’s conflict data confirms that the Assad regime’s commitment to overwhelming and unceasing violence is nothing new. In addition, the data demonstrates just how one-sided the military conflict in the northwest is and has been. This is not to say that rebel or Islamist forces are blameless in the conflict — far from it. However, it is important for us to understand that regime-led violence in Idlib essentially never stops. This constant churn of death and destruction continues to destabilize the humanitarian situation in the area while flare-ups of fighting become vortexes that fuel the geopolitical rivalry between Turkey and Russia. This vector of the Syrian conflict has become so intractable that the U.N.-led Constitutional Committee negotiations in Geneva have had to sidestep the issue altogether to create momentum. So long as the Assad regime’s policy of relentless attacks in the area continues, however, resolution of the wider conflict will remain elusive.

Nick Grinstead is a Non-resident Scholar with MEI's Syria Program. He has been researching dynamics in regime-held Syria for several years now, especially the relations of loyalist militias to the state and with foreign patrons. He also works as a Senior Regional Security Analyst for Le Beck International, a Middle East-based security and risk consultancy. The views expressed in this piece are his own.

Photo by MOHAMMED AL-RIFAI/AFP via Getty Images

[1] Full disclosure: the author previously worked as a Syria researcher for ACLED.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.