July 16, 2023, was a dark day for the ancient city of Damascus. A fire raged through the historic Sarouja neighborhood, reducing a number of heritage homes to ashes. Among the main losses were the Abdul Rahman Pasha al-Youssef Palace, the House of Khalid al-Azem, and the Damascus Historical Museum and Ottoman Documentation Center. Two months later, in September 2023, a residential building in the Syrian capital’s Malki neighborhood partially collapsed as a result of unauthorized excavation for a basement. Interestingly, parts of this building had recently been purchased by Waseem Qattan, a regime-connected and U.S.-sanctioned businessman who already owns dozens of properties in the same district. According to locals, the building’s deterioration appears to have been a deliberate act by Qattan, aimed at pressuring the owners of other apartments in the building to sell their units after they had previously refused. While these events might not seem connected, they underscore an overarching issue: the vulnerability of Damascus properties in the face of natural and man-made crises, exacerbated by corruption, greed, and failed and vicious state policies.

In a city where scarcely a day passes without reports of fires or structural collapses, the discourse about these incidents has taken on a decidedly political tone. Residents blame a variety of factors for the fires, ranging from users’ negligence and electrical faults to climate conditions. Others accuse regime cronies or Iranian militia groups of burning down properties so they can buy them on the cheap. While there may be truth to all of these explanations, this piece is focused on explaining why Syria’s properties are so vulnerable to fires and collapse in the first place. By analyzing 367 mapped fires in Damascus over the year from July 2022 to July 2023, using data on property-related fires collected from the Damascus Fire Regiment’s official Facebook page, we can identify clear patterns around their location, frequency, and the type of property involved.

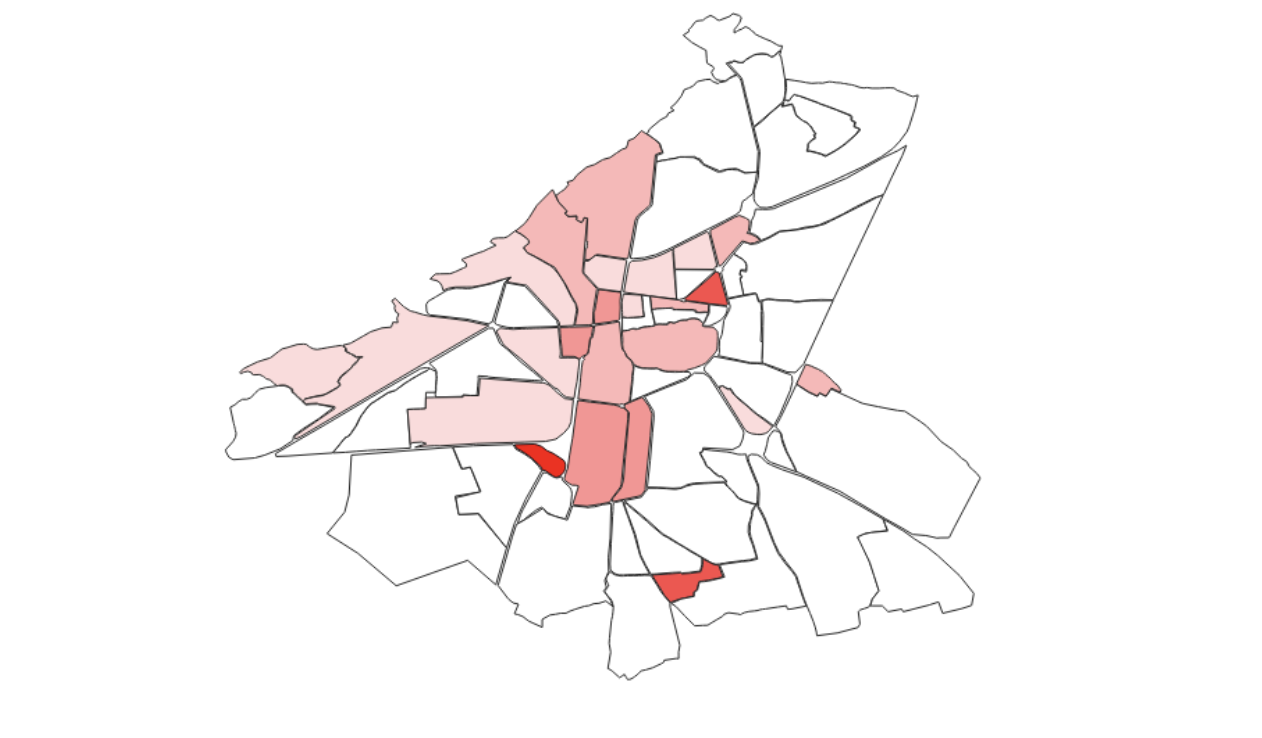

Map 1: Fire density in Damascus (July 2022 - July 2023)

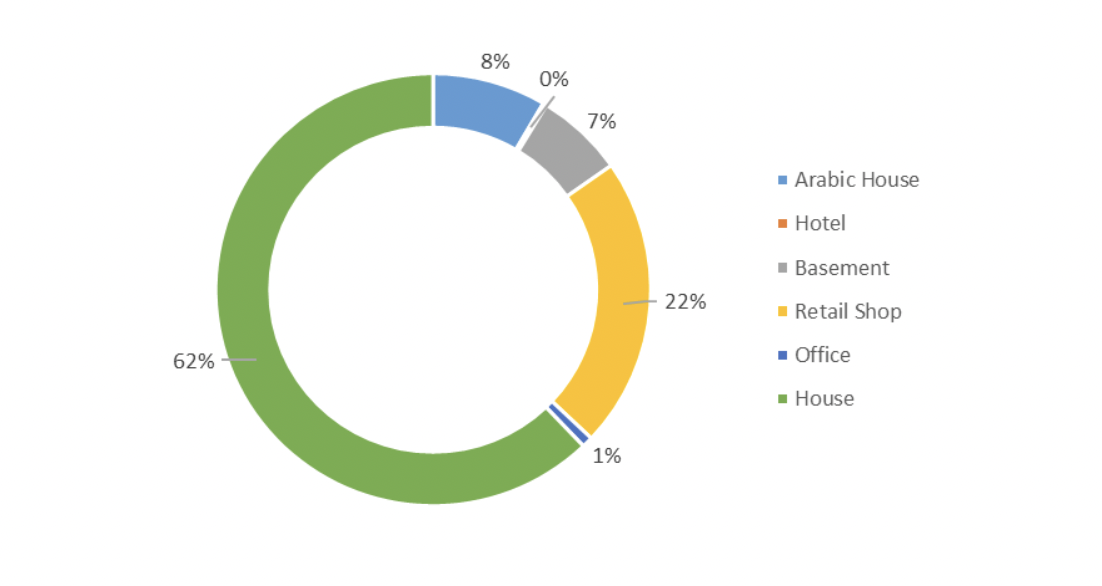

As the data shows, the fires are concentrated in the older neighborhoods of Damascus, dense and informal areas such as Old Damascus, Midan, Zahira, Qasa’, Nahr Eshe, Rukn al-Din, Qanwant, Sarouja, and Hijaz. This pattern is unsurprising given the combination of high urban density and lax enforcement of building codes and safety regulations. The housing sector is clearly the most vulnerable to fires (accounting for 70% of the total), mainly in Midan, Rukn al-Din, and Mezzeh, while the areas with the greatest number of burnt shops are Old Damascus, Midan, Kafr Souseh, Salhieh, and Mezzeh 86. It's worth noting that a considerable portion of the affected houses are historic Damascene homes, known as Arabic houses.

Graph 1: Type of property damaged

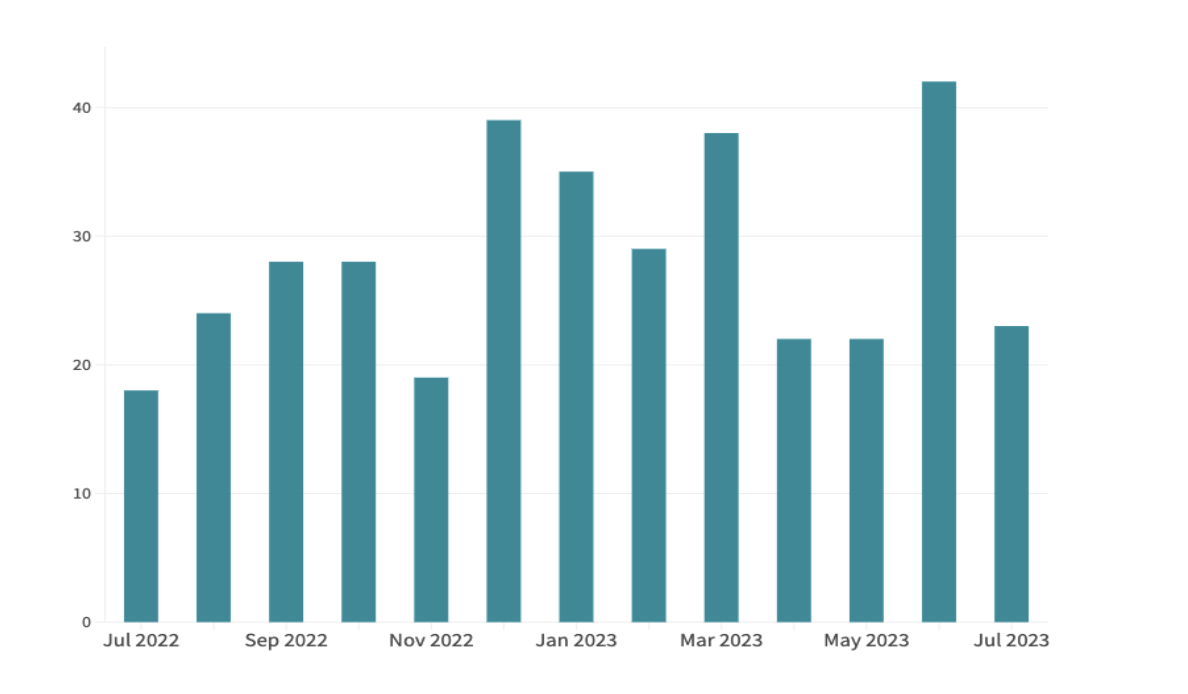

Examining the seasonal distribution of fires provides additional insights. While there is a slight uptick during the winter months, specifically December and January, due to increased heating usage, fires remain consistent throughout the year, with March and June registering a relatively higher incidence. This disputes the notion that environmental factors are the main cause of these fires.

Graph 2: Frequency of fires in Damascus (July 2022 - July 2023)

When we consider that the number of fires has also been consistent in previous years, with 235 fires reported during the first quarter of 2022 and 637 fires in 2021, it becomes evident that the vulnerability of properties in Damascus is a persistent issue. To truly understand the deep-rooted structural, legal, and politico-economic causes of these fires, we must view them as part of a long and complex process that consists of several cycles of deterioration of the urban environment that transcends the fires themselves. Indeed, properties are stuck between a failed state that deprioritizes enforcing safety measures or providing decent housing or basic services, and a corrupt state that not only destroys and depopulates entire neighborhoods but also continues to confiscate properties and impedes rehabilitation efforts. All the while, it enables its business cronies and foreign allies to grab properties for economic and political purposes.

The first phase of this process is related to the overall deterioration of the built environment in Damascus. As far back as 2004, the median age of properties in Damascus stood at 28 years, with at least 40% of them being constructed informally. It's reasonable to doubt whether safety codes, particularly for electrical installations and heating facilities, have been diligently enforced in these informal and historic neighborhoods. Preceding the conflict, practices aimed at maximizing space or reducing construction costs, such as using cheaper (yet more flammable) materials, encroaching on building setbacks, removing structural columns, and adding extra floors, were prevalent even in regulated areas, facilitated by corruption and nepotism. These building violations have escalated during the conflict years due to population density growth, the crumbling of state inspection capacity, and economic deterioration, forcing many to resort to primitive methods of construction (i.e., wood and metal sheets) and heating, such as burning plastic, fabric, and paper.

The second factor is related to the complications imposed by the Syrian regime for property rehabilitation in informal areas and historic neighborhoods, despite the tremendous level of both destruction and degradation in many parts of the city. The regime’s restrictions add to the already unaffordable cost of rehabilitation for the vast majority of Damascenes. Rehabilitation is not possible in informal areas, which are considered building violation areas to be demolished, while in old neighborhoods, properties that are classified as heritage sites (around 6,000 in Old Damascus) are almost impossible to rehabilitate, as in the case of Souq Serije. The inability to restore these properties has resulted in many of them being abandoned for years. A number of them eventually collapsed or were purchased by businessmen, some of whom are linked to the regime, for investment purposes. For instance, between January and February 2023, at least five houses collapsed partially or completely due to lack of maintenance.

The rise of politically connected investors has ushered in a third cycle in the city's degradation. For decades, older neighborhoods of Damascus have been a target for businessmen, and more recently Iranian, Shi’a Syrian, and Russian businesses, which have acquired thousands of properties and historical houses for investment purposes. This gentrification process was facilitated and sponsored by the regime as a part of its neoliberal transformation agenda aimed at benefiting its favored businessmen, in line with confiscations in other parts of the old city, such as Hamrawi, Khan el-Riz, and Souq al-Ateeq, under the pretext of safety or investment purposes, often invoking Law 20 of 1983, which empowers the state to expropriate any private properties for the “public benefit.” In contrast to the previous owners, these businessmen were able to secure rehabilitation permits due to their ties with the Syrian security forces.

Allegations have circulated in Damascus regarding intimidation and pressure imposed on property owners by security forces to compel them to sell, and some properties have burned for “unknown reasons” after the owners refused to do so. Al-Asrounieh Market is the most well-known case in this regard. The UNESCO-listed historical market caught fire in 2016. Locals said that Iranian businessmen attempted to purchase properties inside the market shortly before the fire, but their offers were rejected by shop owners.

State-sponsored rehabilitation of historical sites completes this cycle. Most organizations that once provided funds and small loans to renovate old houses in Damascus have ceased their activities following the rise of the Syria Trust for Development, founded by Asma al-Assad, Bashar al-Assad’s wife, which has effectively monopolized the “business” of heritage sites renovation. However, past experiences with the Trust do not inspire confidence. In January 2023, the Trust rehabilitated the Tikkyeh Sulymaneyeh, one of Damascus’s oldest craft markets, after evicting all of the shops and relocating them to Damascus’s periphery. The market was later included in an investment project led by the Trust’s Syrian Handicrafts. The original craftsmen were not granted new rental contracts to return to once the rehabilitation was completed, and in fact were to be replaced by new traders and craftsmen that had partnered with the Trust — a process that had also played out in Aleppo and Homs. This is likely to be what happens with the Sarouja site too, where the Trust has already taken on the role of overseeing rubble removal and preparing plans for rehabilitation. Furthermore, reports indicating that the Damascus Governorate Council has decided to transfer all crafts that are classified as “dangerous” to areas outside of Old Damascus further confirms such fears. In this context, it isn’t a surprise that the two historical buildings that were burnt in the Sarouja neighborhood, which contained millions of documents providing evidence of ownership as well as records of purchase and sale transactions in the old city, are managed by the Watheqet Watan Organization and the Damascus History Foundation, both of which are managed by Bouthaina Shaaban, Bashar al-Assad’s notorious media advisor, and her daughter Nahid Jawad.

A discernible pattern emerges from this analysis. It is a cycle of urban decay that begins with failed state housing and economic policies and is exacerbated by a concurrent neoliberal push for gentrification and luxury development, often at the expense of providing affordable housing and sensibly rehabilitating heritage sites. Years of conflict, economic collapse, and state negligence have left hundreds of buildings vulnerable to fires, collapse, abandonment, and dilapidation, ultimately rendering them attractive targets for the regime's business cronies, state-sponsored rehabilitation projects, or foreign allies.

Houses are profoundly important as life assets for Syrians. Whether ravaged by war, consumed by fire, or crumbling due to neglect, Syrian properties, like Syrians themselves, continue to suffer from state failure, brutalism, and corruption. It is imperative to recognize that improving the housing sector for Syrians is pivotal not only to ensure the safe return of refugees but also to enable those who remain in Syria to live securely and with dignity. Protecting Syrian properties and heritage must remain a priority for the international community, and doing so will require a combination of measures. This includes providing assistance to Syrians for the rehabilitation of their properties through active NGOs and U.N. agencies. Additionally, easing the process of obtaining rehabilitation permits must be on the agenda in discussions with the regime, including those involving donor countries and U.N. agencies operating within regime-controlled areas. Finally, UNESCO must take serious steps to safeguard the heritage of Damascus. This should go beyond monitoring and condemning to directly engaging with the Syrian regime to facilitate the rehabilitation of heritage houses and the protection of their ownership, involving, if necessary, the U.N. Security Council as well as influential global powers.

Munqeth Othman Agha is a non-resident scholar with MEI’s Syria Program, a doctoral student at the School of International Studies, University of Trento, and a researcher at the Syrian Memory Institute (Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies). He has previously been published by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and Institute of International Affairs (IAI).

Photo by LOUAI BESHARA/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.