Contents:

- With international talks on Iran in limbo, keep an eye on regional action and engagement

- A new redline? NSO revealed to have hacked the phones of US diplomats

- Macron’s Gulf swing displays French diplomatic and security chops

- The formation of the new Iraqi government: Strategic shifts, tactical changes

- Council of Europe takes action against Turkey over Kavala case

- Pakistan finds negotiating with Islamists vexing

With international talks on Iran in limbo, keep an eye on regional action and engagement

Brian Katulis

Vice President for Policy

With no major breakthroughs and few encouraging signs coming out of international talks on Iran’s nuclear program in Vienna last week, U.S. officials are sounding a much different tone than the Biden administration did when it entered office about the prospects for a new deal. The fact that Iran continues to accelerate its nuclear program and showed up at the latest round of talks with maximalist demands has led the Biden administration to look at all available policy options, and it’s publicly talking about a new round of sanctions and more diplomatic moves to isolate and put pressure on Iran.

As the United States discusses Plan B options on Iran, it should keep a close eye on regional security and diplomatic trends and seek to more actively shape these trends toward a more positive direction. Tensions between Israel and Iran remain high, particularly in cyberspace, and Iran has continued to target America and its regional partners in a series of destabilizing attacks this spring and summer.

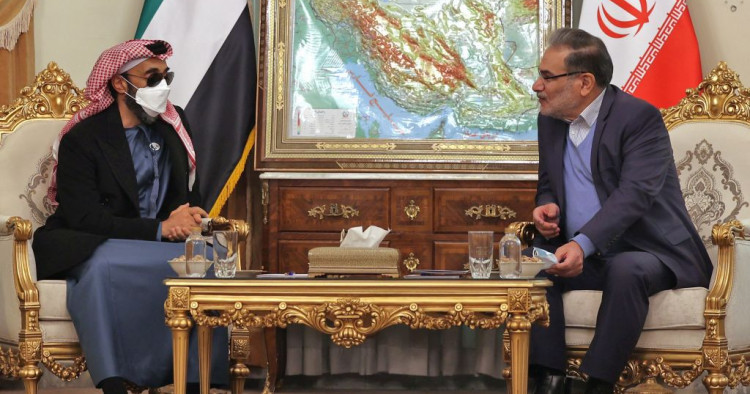

At the same time, regional tensions have incentivized new diplomatic channels between Iran and its neighbors, most recently today’s visit by the Emirati national security advisor, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan, to meet with officials in Tehran. This diplomatic engagement comes after more than a year of quiet talks between Iran and its Gulf neighbors, including Saudi Arabia, and contacts at a regional conference hosted by Iraq in August. None of this diplomacy has yet led to major breakthroughs on the negative regional security dynamics or the nuclear file. But they are important reminders of the broad range of tools available in any discussions about Plan B strategies on Iran — one key tool that remains essential is diplomacy.

In many ways, the nuclear issue is just one of many important security questions including ballistic missiles, support for terrorism, cybersecurity, and maritime security that impact the broader stability of the Middle East. For years, Iran’s leaders have sought to keep the nuclear issue separate from the other issues impacting regional security. As U.S. officials look to formulate alternatives to their initial playbook on Iran, they should examine ways to make the regional political and security landscape more favorable to its closest partners, and keep open every avenue for diplomacy, backed by a balanced regional security strategy.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

A new redline? NSO revealed to have hacked the phones of US diplomats

Eliza Campbell

Director, Cyber Program

Adding to this year’s ramping up of international outrage toward and scrutiny of the Israeli-based firm NSO Group, it was revealed last week that the company’s signature product, the spyware tool Pegasus, was used to hack the phones of at least nine U.S. diplomats. The hacks appeared to take place over the course of the past several months, at a time when further revelations were coming out about use of NSO’s spyware against, among others, several Palestinian rights groups, and in the wake of revelations from the consortium of media partners known as the Pegasus Project about how the company’s spyware may have been used to target 50,000 persons of interest around the world, including up to 180 journalists. The U.S. State Department employees in question were based in Uganda, or worked on issues relating to the country.

These revelations shed further light on the Biden administration’s seemingly abrupt decision to place NSO Group and several other firms on a blacklist earlier this year, after the Department of Commerce cited breaches against, among other people, activists, journalists, and dissidents, and specifically mentioned the threat of spyware being used against embassy workers. This latest hack is the first reported case of Pegasus being used against American officials, and makes the phones of those its targets vulnerable to extractions of encrypted communications, photos and videos, as well as precise location data. It is not difficult to imagine government officials around the world being interested in tracking the real-time communications and location of U.S. diplomats, and the potential consequences of normalization of this practice would be likely to upend many accepted norms and assumptions about the U.S. and its relationship to allies and adversaries. NSO has maintained that it does not hack the phones of U.S. nationals, but reporting has shown that its mechanism for enforcement is not deploying its spyware against any mobile phone number beginning with the “+1” U.S. national code. Since the diplomats in question used local phone numbers, as many U.S. nationals working or living abroad often do, this protection proved null, and raises questions about the extent to which firms that produce spyware and other hacking tools are actually able to enforce privacy protections or act in accordance with international norms of human rights, as NSO, for its part, has claimed.

The Biden administration has shown an increasing willingness to take on the question of hacking tools as a matter of potential disruption to both U.S. national security and international human rights. Meanwhile, activists, journalists, dissidents, and citizens of non-democratic countries have spent years begging the U.S. and international bodies to take seriously the disastrous consequences of an international order that normalizes the deployment of privately sold and distributed spyware and surveillance software. Israel, a major U.S. ally and defense partner, continues to be a primary market for many technology tools that have proved alarming to rights advocates, and the country has more openly deployed the export of such tools as a form of diplomacy, even to authoritarian and brutally repressive regimes around the world. The consequences of this reality for the U.S.-Israel relationship have yet to be seen. In any case, as others have noted, it seems inevitable that powerful parties interested in hacking and surveilling those that speak truth to their power, including journalists and activists, will eventually be tempted by other targets, such as diplomats and government officials. The question that remains is how and when the U.S. will take this threat seriously, and recognize that a threat to privacy anywhere will eventually be a deadly serious matter everywhere — including at home.

Macron’s Gulf swing displays French diplomatic and security chops

Gerald M. Feierstein

Senior Vice President

As President Emmanuel Macron gears up for what could be a grueling campaign for re-election next spring, his early December swing through the Arab Gulf states has served to highlight French diplomatic and military importance and burnished his credentials as a leader who can keep France on the world stage. Most significant for Macron’s credibility is the sale of 80 French Rafale fighter jets to the UAE, worth an estimated $18 billion. For a defense establishment still agonizing over the lost $60 billion Australian submarine deal to its U.S.-U.K. rivals, the sale to its long-time defense partner in Abu Dhabi offers a welcome revival of fortunes.

Of equal benefit from the Macron visit, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) and Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati both advanced their interests through Macron’s diplomatic engagement. As the first world leader to meet with MbS since the Khashoggi murder, Macron’s visit to Riyadh marked a significant step forward in the crown prince’s political resurrection. Afterwards, Macron told the press that his discussions with MbS covered a broad agenda of bilateral issues, including economic and energy issues, Yemen, Iran, and Iraq. There were “no taboos” in the meeting, Macron said.

Perhaps Macron’s most substantial diplomatic success came in securing from the Saudi crown prince an agreement to re-engage with Lebanese Prime Minister Mikati, after former Lebanese Minister of Information George Kordahi, whose faux pas triggered the diplomatic crisis with Riyadh, resigned. On a joint phone call to Mikati, Macron and MbS pledged to cooperate in helping Lebanon emerge from its deepening economic meltdown.

Most importantly for the French leader’s election prospects, his successful swing through the Gulf, which included a stop in Doha as well, provided an opportunity to showcase his diplomatic and strategic prowess. In doing so, he established a clear contrast to the struggles of his U.S. counterpart. President Joe Biden’s continued refusal to deal directly with MbS complicates U.S.-Saudi relations. His diplomatic initiatives to promote a resolution of the Yemen conflict and a return to the Iran nuclear deal remain stymied. And questions persist throughout the region over the reliability of the U.S. as a diplomatic and security partner.

The formation of the new Iraqi government: Strategic shifts, tactical changes

Shahla Al-Kli

Non-Resident Scholar

The election of Oct. 10, 2021 brought about three major strategic shifts in the Iraqi political process that, although they have yet to yield fundamental changes in the current government formation process, have huge potential to result in more substantial changes in the future. First, the pro-Iranian factions across the Iraqi political lists and parties, whether within the Kurdish, Sunni, or Shi’a blocs, have lost substantially. Second, the parties that grew out of the popular protests of October 2019, Imtidad and Ishraqat Kanun, won 9 and 6 seats respectively in their first electoral contest. Third, there has been a consolidation of the leadership of the Shi’a political parties under Muqtada al-Sadr and Nouri al-Maliki, of the Kurds under the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), and of the Sunnis under current Speaker of Parliament Mohammed al-Halbousi. In a fourth key development after the election, the Iranian-backed Iraqi militias’ ramshackle tactics have revealed the extent and limits of their capabilities and ability to disturb the political process and Iraq’s stability. These shifts are rooted in and have emerged from changes in Iraqi society and are part of the trends of increasing socio-economic and political maturity that are still ongoing across Iraq despite all the efforts to disrupt and suppress them. Concurrently, these strategic shifts are also a manifestation of the quiet diplomacy taking place among the regional powers and key players, as highlighted by the Saudi-Iranian talks, the Turkish-UAE high-levels visits, the renewal of Syria’s relations with the other Arab countries, and the Jordanian-Egyptian-Iraqi energy/electricity connections.

However, the Iraqi government formation process is still marked by short-term decision making, lots of horse trading with little or no strategy, and the traditional “political marketization” of senior government positions starting with, and most importantly, the role of prime minister. The strategic shifts brought about by the October election have long-term impacts and will depend on similar outcomes in subsequent elections for Iraq to witness a fundamental structural change in the nature of its political process and governance policies. The importance of the October election is that it has revealed the actual size, power, influence, reach, and capabilities of the Iranian-backed Iraqi militias and Iranian political proxies within the Iraqi political process, which in turn can empower and facilitate new homegrown political parties. Currently, both Shi’a camps, al-Maliki/Hadi al-Amiri and al-Sadr, are using multiple tactics to reach a consensus on selecting a candidate for prime minister and sharing the government spoils, which then will facilitate launching negotiations with the Kurds and Sunnis — an approach that is, in essence, not that different from previous government formation processes in Iraq and is highly unlikely to yield the necessary changes in governance. Iraq’s political process still needs two to three more elections to be wholly transformed, but the October election is a significant milestone along the way.

Council of Europe takes action against Turkey over Kavala case

Gönül Tol

Director of Turkey Program and Senior Fellow, Frontier Europe Initiative

Europe’s top human rights body, the Council of Europe, launched “infringement proceedings” against Turkey over its refusal to release Osman Kavala, a philanthropist who has been detained for four years on farcical charges without any conviction. The move, announced on Dec. 3, came after a Turkish court extended the imprisonment of Kavala despite a 2019 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights that said his jailing without conviction was political and urged Ankara to free him. The infringement process could lead to the suspension of Turkey’s voting rights and its expulsion from the Council of Europe, which Turkey has been a part of since 1950. This would sever a key link to Europe at a time when Turkey’s relations with the West are severely strained. Human rights lawyers argue that the Council of Europe’s latest move leaves Turkey with no options other than to release Kavala, but there is ample reason to be pessimistic.

The case against Kavala is personal for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He accuses Kavala of organizing the 2013 Gezi Park protests when hundreds of thousands of people across the country marched to protest Erdoğan’s authoritarian policies. The protests, which came as a shock to Erdoğan, became a turning point. It fueled his paranoia and divided the country further. Erdoğan says Kavala is also behind another key event during his years in power: the 2016 failed coup. But Kavala’s pro-Kurdish stance may be his worst sin in Erdoğan’s eyes. Kavala has been a longtime supporter of minority rights in Turkey, including Kurdish rights. In 2015, the electoral success of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) under the leadership of its co-chair Selahattin Demirtaș shook Erdoğan’s rule, denying his party the parliamentary majority that it had enjoyed since 2002. To Erdoğan, Kavala and Demirtaș’ decades-old struggle for Kurdish rights became the biggest stumbling block in his quest to grab unchecked power. Within two years, both men were behind bars. The European Court of Human Rights calls for Demirtaș’ release as well. But Erdoğan’s personal vendetta against both men means there is little prospect that the ludicrous charges against them will be dropped.

Follow on Twitter: @gonultol

Pakistan finds negotiating with Islamists vexing

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

Not long ago it seemed that peace was in the air in Pakistan. After threatening to undermine the Imran Khan government and paralyze the nation’s economy, the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) religious protest movement signed an agreement with the government in early November calling off the party’s nation-wide demonstrations. More recently it was revealed that negotiations had quietly begun between members of the Pakistan Taliban, the Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP), and government representatives that could end a bloody insurgency that has stretched over 14 years. Both of these peace initiatives have proven disappointing, ultimately for some very similar reasons.

With agreement on terms at first kept undisclosed, the TLP ended its increasingly violent protest march on Islamabad with the understanding that the Khan government would release the party’s chief Saad Rizvi, along with more than 2,000 party activists. Khan’s cabinet also agreed to revoke a declaration that had banned the TLP as a terrorist group, and the Punjab provincial government removed Rizvi’s name from an anti-terrorist watchlist. In exchange the TLP agreed to denounce violence and withdraw its demand that the government expel the French ambassador after a French satirical magazine had reprinted cartoons from 2012 the party labeled as blasphemous.

But the government’s deal with the TLP raised eyebrows. Many of the arrested TLP activists had participated in late October in a violent confrontation at a rally that resulted in the death of four policemen and numerous civilian casualties. Khan’s own Minister of Information Fawad Chaudhry expressed what many other Pakistanis were feeling — that the government had, as in previous standoffs with the TLP, “retreated.” Not willing to appear to concede on anything, the TLP leaders announced that they had in fact never insisted on the ambassador’s ousting. The leaders also made it clear that the party had no intention of ending its mass mobilizations to press its cause of full compliance with blasphemy laws and would, if necessary, resume its protest march. That the mainstream appeal of the TLP runs strong was well demonstrated last week by an incident in Sialkot when a mob chanting the group’s slogans lynched a Sri Lankan business manager accused of blasphemy.

Late last month the Khan government revealed that it had quietly met with elements of the TTP’s leadership and arranged for a month-long cease-fire, during which it would discuss a more permanent end of hostilities. Opposition politicians were angered that the peace overture was not discussed in parliament and were skeptical of talking with those with so much blood on their hands. In the course of three rounds of talks facilitated by Afghan Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, who is on the U.S.’s terrorist list, the TTP negotiators indicated as their bottom line that Pakistan must become a “true” Islamic system. The government quickly rejected the idea that Pakistan was not already an Islamic state and countered with the similarly hardline approach that the TTP would have to accept the writ of the state, lay down its arms, and publicly apologize for its past terrorist acts.

Negotiating with the TLP and the TTP, one an Islamist protest group, the other an Islamist insurgent movement, is highly unlikely to result in sustainable agreements. Politically, much of Pakistan’s ruling class finds it impossible to accommodate groups whose understanding of the role of government is so antithetical to their own convictions. Conversely, the TLP and the TTP, in their missions of purifying Pakistan as an Islamic state, resist compromising on any issues that define them as movements.

This article was co-authored by Makhdum Karam Shah, research assistant to Marvin G. Weinbaum.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.