Contents:

- Wrapping up UNGA week: How did MENA issues and leaders fare?

- Israel’s UNGA week: Pro-democracy protests, Saudi normalization, and incentives for peace with the Palestinians

- Flurry of lost opportunities: Iran’s Raisi leads disjointed diplomatic mission to UNGA

- Developing nations need help, and a voice

- Will Qatar replace France as the main mediator on Lebanon?

- Next steps for US Middle East policy after UNGA 2023

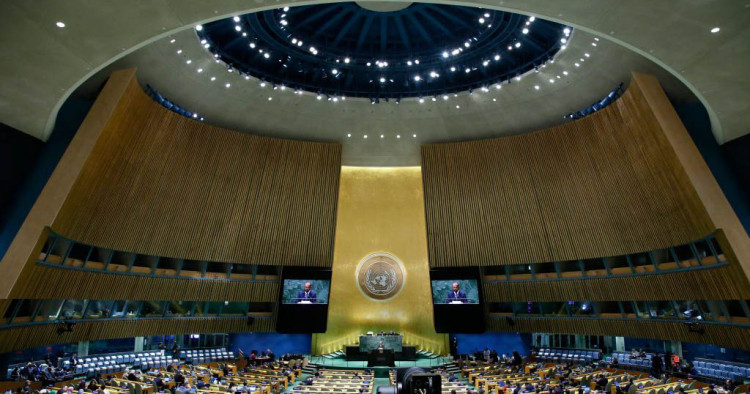

Wrapping up UNGA week: How did MENA issues and leaders fare?

Paul Salem

President and CEO

-

The meetings surrounding the United Nations General Assembly last week showcased both vigorous diplomacy and the growing role in regional and global issues of a number of Middle Eastern leaders.

-

International leaders, diplomats, U.N. officials, and independent experts met in various settings and forums to discuss topics ranging from Saudi-Israeli normalization, resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, climate change mitigation financing, the war in Yemen, disaster relief in North Africa, and intra- and trans-regional infrastructure development.

The international meetings surrounding the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in New York, which wrapped up late last week, showcased both vigorous diplomacy and the growing role of a number of Middle Eastern leaders in both regional and global issues.

On the sidelines of the proceedings, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had what is believed to be his first in-person meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, after which Turkey’s leader announced progress on discussions relating to energy drilling and transport routes as well as potential bilateral cooperation on technology and tourism. Netanyahu, in turn, also met with U.S. President Joe Biden, and the two emphasized their commitment to work toward a Saudi-Israeli normalization agreement.

Saudi Arabia garnered most notable attention outside of the New York meetings, thanks to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (often referred to as MBS) extensive interview with Fox News, which aired in the middle of UNGA week. In his responses, MBS underlined Saudi Arabia’s strong relationship with the United States and affirmed his country’s interest in normalizing relations with Israel, provided the latter could offer meaningful concessions to the Palestinians. The Saudi leader as well as President Biden both emphasized that moving toward reviving the two-state solution as a viable outcome for the Israel-Palestine conflict was essential to making progress on an American-brokered Saudi-Israeli deal. Saudi Arabia, along with the Arab League, the European Union, Egypt, and Jordan, hosted a meeting on Middle East peace on Monday to highlight the need for progress on Palestinian issues.

On the Iranian track, the main event also came from outside the New York meetings, with the announcement on the first day of UNGA week of a U.S.-Iranian prisoner swap and the unfreezing of $6 billion of Iranian assets, to be used for humanitarian purposes. The deal came amid statements from Iranian officials, preceding UNGA week, that they were interested in negotiations to revive the largely defunct Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Iran’s nuclear program. There was no visible progress on that file during the New York meetings, but it is something to watch in the coming months.

The situation in Yemen, on the other hand, received significant attention. The head of the Yemeni Presidential Leadership Council addressed the General Assembly, and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with his Saudi and Emirati counterparts on the Yemeni issue as well. The high-level gatherings in New York came after five days of talks between a Houthi delegation and Saudi officials in Riyadh. That meeting was the first of its kind since the start of the Yemen conflict in 2014. Both sides announced significant progress toward the reopening of Houthi-controlled ports and Sanaa airport, payment of wages for public servants, rebuilding efforts, and a timeline for foreign forces to leave Yemen. This progress appears to be one of the positive side effects of Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, and could lead to further U.N.-led negotiations to restart a wider Yemeni-Yemeni peace process.

On Syria, Jordanian and other Arab and Turkish officials confirmed that there had been no progress or positive response from Bashar al-Assad’s regime after its readmission into the Arab League, noting that the way forward in Syria remains fully blocked. Whereas, on Lebanon, members of the “quintet” (U.S., France, Saudi, Qatar, and Egypt) met but did not issue a joint communiqué, indicating what some reported was sharp disagreement with Paris over its approach and a larger role for Doha in the coming period. For Egypt, general dismay prevailed that the country has entered a deep economic crisis for which the current government has no solution, and which threatens further socio-economic hardship for its already struggling population.

The natural disasters in Morocco and Libya received their share of focus, led by the United Nations’ Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths. The U.N., especially the UNDP, was proud to tout its success of organizing the offloading of over 1 million barrels of crude oil from the aging Safer tanker and thus averting an ecological disaster that would have devastated the livelihoods of millions along both shores of the Red Sea.

The members of a new regional initiative, called the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), which was just announced at the G20 and includes the United States, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy and the European Union, received added momentum with statements of support from President Biden and other member state leaders. The members of another regional effort, called I2U2, which brings together India, Israel, the UAE, and the U.S., also met in New York to boost economic and infrastructure ties.

The global agenda of UNGA week featured strong representation from the MENA region as well. The Climate Ambition Summit, assembled by U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, emphasized the need for more rapid global progress on climate goals. The U.N. Climate Change Conference is transitioning from COP27 in Egypt to COP28, to be held in November-December of this year, in the UAE. Sultan Jaber, COP28 president-designate and the UAE’s climate envoy, addressed the high-profile audience in New York and emphasized the need to mobilize large-scale climate-related finance to bridge the annual $2.4 trillion gap that will be needed to keep the world on track with its climate goals in 2030.

The U.N. additionally convened a summit meeting on gaining lost ground in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian war in Ukraine, high interest rates, and inflation are all factors that have negatively impacted many countries’ progress on the SDGs. Many oil-importing countries in the MENA region are among those negatively affected. Here too the issue of marshaling global finance to create a more supportive and just global financial architecture was a key part of discussions in New York. Key Gulf petroleum producers, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, have much to contribute — directly or through their sovereign wealth funds and private businesses — in addressing some of these needs.

The agenda was not limited to governments. The Middle East Institute and Think Research and Advisory convened a high-level conference in New York this past Friday in which U.S. and international officials and experts addressed many of the issues raised above.

All in all, the flurry of diplomacy during UNGA week 2023, in New York, emphasized the importance of diplomacy and showcased the prominent role of a number of MENA countries in addressing both regional and global challenges.

Follow on Twitter: @paul_salem

Israel’s UNGA week: Pro-democracy protests, Saudi normalization, and incentives for peace with the Palestinians

Nimrod Goren

Senior Fellow for Israeli Affairs

-

At this year's UNGA, Israel and Saudi Arabia publicly indicated an interest in normalizing ties, a process that is already underway; UNGA also gave birth to a new multilateral effort to advance Israeli-Palestinian peace, which Israel seem to be willing to de facto engage with.

-

Throughout Netanyahu's visit to the U.S., he was confronted by pro-democracy protesters, Israelis and American Jews alike.

The UNGA high-level week is a key fixture in the Israeli diplomatic calendar. It typically produces headlines related to the Israeli prime minister's speech, the leaders he meets on the sidelines, and statements and actions regarding the Palestinians or Iran.

This year's UNGA had it all: A speech by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on regional opportunities and the Iranian threat, using controversial props; side meetings with U.S. President Joe Biden and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, among others; a walkout protest against Iran's president by the Israeli ambassador to the U.N.; and a speech by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas emphasizing the need to establish a Palestinian state.

But 2023 is no typical year when it comes to Israel — neither domestically nor regionally. Netanyahu's trip to the U.S., which did not include a White House visit but did include a West Coast leg to meet tech billionaire Elon Musk, was accompanied by pro-democracy protests, from start to finish. Pro-democracy Israelis and their partners from the U.S. Jewish community mobilized large numbers of protesters and made their voices heard at every stop of Netanyahu’s trip. It was an international success for the Israeli pro-democracy movement.

Policy-wise, UNGA produced headlines on Israel-Saudi relations. Netanyahu stressed just how close Israel has come to normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman reaffirmed this in an interview with Fox News. "Every day we get closer," he said when asked about normalization with Israel, specifying that this will require measures to “ease the life of the Palestinians” — far less than the usual Saudi demand for a Palestinian state, as specified in the Arab Peace Initiative.

These public messages were coupled with gestures — Israeli and Saudi representatives attended both countries' UNGA speeches, and Saudi Arabia stepped up its opening toward Israel. Days before the General Assembly, the kingdom allowed, for the first time, an official Israeli delegation to publicly participate in a multilateral event (a UNESCO meeting) in Riyadh. This followed on from previous delegations of Israeli businesspeople with foreign passports and Israeli gamers and athletes competing in international events in the country. Saudi Arabia is now routinizing open engagement with Israel. The United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco did the same in the lead up to their normalization agreements with Israel. The Israel-Saudi normalization process is thus already under way, and its completion seems to be an issue of timing and diplomatic constellation, not of strategic decision.

And, finally, UNGA week marked the launch of a new multilateral effort to present incentives for Israeli-Palestinian peace, the “Peace Day Effort,” co-chaired by the EU, Saudi Arabia, the League of Arab States, Egypt, and Jordan. Israel, like the Palestinians, was not invited to participate in the launch event. But, unlike its opposing and dismissive reactions to previous non-U.S.-led international peace initiatives, this time Israel has shown a de facto willingness to engage, with Foreign Minister Eli Cohen being debriefed on the issue by EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell and inviting him to visit Israel later this year.

Seeds for regional diplomatic progress have been planted at this year's UNGA. Whether or not they will grow and bud soon will largely depend on if Netanyahu shelves his judicial overhaul and marginalizes his far-right coalition partners after returning home from New York.

Follow on Twitter: @GorenNimrod

Flurry of lost opportunities: Iran’s Raisi leads disjointed diplomatic mission to UNGA

Alex Vatanka

Director of Iran Program and Senior Fellow, Black Sea Program

-

President Raisi could have used the visit to UNGA to initiate a genuine attempt at advancing the cause of dialogue with the West, but instead he sought to entice the sympathies of the non-Western world — though without a clear policy goal.

-

While Raisi’s speech at the U.N. attacked the U.S., Foreign Minister Amir-Abdollahian tried to secure a visit to the American capital, showing that Tehran has yet to seriously make up its mind when it comes to relations with Washington.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s visit to the U.N. in New York was a lost opportunity. That seems to be the majority opinion in Tehran. His trip overlapped, perhaps intentionally, with Iran’s release of five American hostages. Raisi could have used this moment to initiate a genuine attempt at advancing dialogue with the West. But the Iranian leader was not in New York to appeal to American or Western audiences; rather, he sought to entice the sympathies of the non-Western world — although not for a specific policy reason, as pointed out by his critics.

From his speech at UNGA to his meetings with select American audiences, Raisi did what every president of Iran has done at the U.N. since 1979: air a long list of grievances against the West, and particularly the United States. At the same time, he sought to deflect at every turn. He deplored the treatment of indigenous people in Canada and the Palestinians by Israel, all the while dismissing any concern about the terrible human rights situation in Iran as a case of Western double-standards.

Aside from photo-ops with counterparts from around the world, Raisi exhausted himself defending the Islamic Republic’s record, but failing to achieve a singular tangible diplomatic aim while in Turtle Bay. For this, he came under sharp criticism from certain corners back in Tehran. As the non-regime media in Iran noted: Why bother to spend all this money and travel to New York when Raisi was not after anything specific? After all, attending the annual U.N. General Assembly is optional for world leaders.

Raisi’s condemnations of the U.S. at the U.N. were hardly a surprise. But the disjointedness of his delegation’s goals still puzzles. While the Iranian president delivered his requisite verbal attacks, his foreign minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, was reportedly seeking permission to visit the Iranian interest section in Washington, D.C. Whatever his motivation, Amir-Abdollahian surely knew of his boss’ planned tirade against the host country when he asked to visit Washington. Why would Tehran have presumed that the Biden administration — or any U.S. government — would let Iran have its cake and eat it too? The takeaway is clear: Tehran has yet to seriously make up its mind when it comes to relations with Washington.

Follow on Twitter: @AlexVatanka

Developing nations need help, and a voice

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

-

At UNGA, world leaders adopted a political declaration that addresses two increasingly urgent demands of developing countries: debt relief and a rethink of international finance systems.

-

Developing nations are starting to chafe at an order that refuses to take their interests into account.

Last week in New York, U.N. General Assembly President Dennis Francis pointed out that despite previous commitments, there were 1.2 billion people still living in poverty as of 2022. Worse still, 680 million people — about 8% of the earth’s inhabitants — would still be facing hunger by the end of the decade. The international community cannot accept these numbers, he said.

Apparently, it can.

The U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted with great fanfare in 2015. They were designed to “leave no one behind” and included ending extreme poverty and hunger as well as ensuring access to essentials like clean water and sanitation, affordable green energy, and quality education. The thinking was that developed nations would step up and help developing countries achieve their potential. It hasn’t quite worked out that way though. To date, of the 17 SDG goals (which comprise 169 targets in all) only 15% are on track, warned U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, with many actually sliding backwards. There is reason to hope, however. At UNGA, world leaders adopted a political declaration to speed up action on reaching the 17 goals. The secretary-general called it a possible “game-changer in accelerating SDG progress."

The declaration includes financing for developing countries. More importantly, it also includes concrete support for Guterres’ SDG stimulus of at least $500 billion annually. That’s essential because despite previous promises, developed nations have so far come up staggeringly short when it comes to backing up goodwill with actual financial support. Just as importantly, the declaration addresses two increasingly urgent demands of developing countries: debt relief and a rethink of international finance systems.

The two are inextricably linked. Several representatives from emerging economies, among them the prime minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, and the foreign minister of Egypt, Sameh Shoukry, made it a point to emphasize the importance of debt relief to emerging economies, struggling to deal with burgeoning debt payments and the costly repercussions of climate change. Mottley noted such relief was vital in helping combat disaster scenarios, saying it made sense to “offer limited access to concessionary finance for climate-vulnerable countries so they can adapt and build resilience and sustainability.” Shoukry pressed for a reorganization of the international financial institutions, which many developing countries feel have imposed unfair interest rates and financial blockades.

Ultimately, it’s in the interest of developed nations to reconsider their approach. Western nations tend to refer to a “liberal international order” because it’s one that they have imposed. However, the geopolitical landscape has shifted. Developing nations, most notably the Global South, are starting to chafe at an order that refuses to take their interests into account if those interests do not align with Western ones. The international clout of China and the rising power of India, and, to a lesser extent, rich Gulf nations, as well as the stubborn refusal of Russia to play a diminished international role should be sending clear signals that geopolitics is no longer business as usual. And that realization should be accompanied by an understanding that maintaining influence with the developing world will require incentives: real financing for development and climate change and, just as importantly, a future dictated by their own needs and priorities rather than those of others.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

Will Qatar replace France as the main mediator on Lebanon?

Fadi Nicholas Nassar

U.S.-Lebanon Fellow

-

Caretaker Prime Minister Mikati’s UNGA speech and interview with Le Figaro appears to be part of an effort to restore his international standing following Lebanon’s rapid descent into a failed quasi-authoritarian state.

-

Yet, perhaps the most noteworthy statements on Lebanon at UNGA came from Qatar’s emir, who appeared to position Doha as taking a leading role in the quintet on the Lebanon file, at the expense of France’s traditional leadership position.

Addressing the U.N. General Assembly, Lebanon’s caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati drew attention to the critical state the country is in. Mikati began his address by recalling Lebanon’s historic role as a founding member of the United Nations and a key participant in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. His speech continued to then stress the toll of the concurrent crises devasting the country. Mikati’s speech, read alongside his recent interview with the French newspaper Le Figaro, appears to be part of an effort to restore his international standing following Lebanon’s rapid descent into a country perpetually hovering on the precipice of state failure, which has defined his tenure.

More than three-quarters of the country’s population lives in poverty, the local currency has lost almost all its value, and the domestic investigation into the Port of Beirut blast has been obstructed, all while a series of leadership vacuums leave Lebanon without a president, functioning government, or Central Bank governor and no meaningful reforms have been enacted. Full responsibility for Lebanon’s concurrent crises certainly does not fall on the caretaker prime minister, as no reforms were made before his period of leadership either; indeed, he has historically been a rather transitionary figure and often played a somewhat mediating role, even if falling more within the Hezbollah-Bashar al-Assad circle of influence. Still, Mikati is no bystander, and his record at the helm has significantly stained his reputation in and outside Lebanon. Indeed, without taking away from the parliament’s failure to vote on the respective laws, Mikati’s government did not follow through with an International Monetary Fund (IMF) reform deal under his tenure. Lebanon also failed to conduct municipal elections “on time.”

Paris, which largely led the Lebanon file for the group of five, or “the quintet,” consisting of Qatar, Egypt, the United States, France, and Saudi Arabia, supported Mikati early on as a credible political operator and potential reformer. But the subsequent absence of any credible Lebanese reforms to materialize undermined French credibility and reinforced local concerns that Paris’s mediation was focused on maintaining the façade of state institutions at the expense of real changes — having leaders in name only, overseeing institutions either unable or unwilling to perform their core functions and conceding to obstruction rather than containing spoilers. France’s most striking blunder in this regard was its effort to mediate an end to Lebanon’s presidential void by reaching a consensus between Assad ally Suleiman Frangieh as president and a more technocratic-leaning head of government. The proposal of returning Lebanon’s presidency back under Assad’s sphere of influence significantly drained French credibility and leverage. In his recent interview with Le Figaro, Mikati appeared to rehash the underlying principle behind that initiative by stressing his belief that “it would not be logical, or even reasonable, to elect a president who would antagonize Hezbollah.” While the remarks help situate his position on the perimeters of Hezbollah’s influence, the logic behind this position is also what cost France its decades of diplomatic capital and leverage in Lebanon — that purportedly the only answer to Hezbollah’s obstruction and coercion was to legitimize and reward it by conceding to it. France’s failed approach to Lebanon suggests a compatibility with the politics that have come to define Mikati’s career.

In a sense, Mikati typifies the kind of dysfunctional Lebanese politics that succeeds by deliberately being seemingly inconsequential, avoiding sufficiently alienating the major local, regional, and international stakeholders, all while helping establish a status quo that gravitates around Hezbollah’s security interests. To be clear, Mikati’s approach and France’s compatible “consensus” formula should not be confused with “compromise politics” that are often associated with power-sharing democracies like Lebanon. On the contrary, Mikati exemplifies Hezbollah’s ideal prime minister, giving the militant group a head of the government who prioritizes its security interests but is able to maintain friendly (enough) relations with Western governments and the Gulf countries. Similarly, France’s false consensus failed because it sought to further establish Hezbollah’s security dominion while maintaining an inconsequential head of government that would attract international and regional engagement and could be dumped if ever “antagonistic” to Hezbollah.

Mikati’s UNGA speech notwithstanding, perhaps the most noteworthy statements on Lebanon last week came from Qatar’s emir, Shiekh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, who stressed the need for international solidarity and an end to Lebanon’s protracted political vacuum. His remarks appear to suggest Doha might play a leading role in the quintet on the Lebanon file. So far, Qatar has distanced itself from France’s proposal of a consensus on Frangieh and instead seems to be backing the head of Lebanon’s army as a potential candidate to fill the void, if chosen by the Lebanese. It is still too early to tell what Doha’s vision of a potential solution to Lebanon’s protracted impasse may be or if Paris will accept having to take a back seat. In October, French and Qatari diplomats responsible for Lebanon will be in the country, presenting a critical period to observe if the quintet further fragments or rallies behind one mediator, coalescing around a united position on Lebanon.

Follow on Twitter: @dr_nickfn

Next steps for US Middle East policy after UNGA 2023

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

-

As usual, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East didn’t change that much at UNGA; instead, it was a week for staking out positions and grandstanding, rather than taking concrete steps toward producing progress on particular policy issues.

-

Back in Washington, the looming threat of a U.S. government shutdown raises an important question: If America’s political leaders can’t agree on basic things like funding the government, how in the world will they build a consensus to address contentious foreign policy issues?

As the U.N. General Assembly annual session winds down, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East looks much the same as it did before the week started. This was expected because the spotlight in this annual meeting was largely on wider global issues, like the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, the reform of multilateral banks, cooperation on global infrastructure investment, and a meeting of the coalition on synthetic drug threats, among other issues. U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East didn’t change that much at UNGA, which is what usually happens most years.

If anything, the UNGA meetings served as a forum for leaders from the region to reassert their long-standing positions and peddle the latest iteration of their wish lists, as was the case with Israel’s prime minister and the Palestinian Authority’s president. Iran’s president repeated Tehran’s threats to take revenge against the United States for its 2020 strike that killed Qasem Soleimani, a top commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, reducing any limited hopes for reviving wider talks between the United States and Iran after a prisoner exchange deal at the start of the week. It was a week for staking out positions and grandstanding, rather than taking concrete steps toward producing progress on particular policy issues in the broader Middle East.

The Biden administration did its share of restating its policy stances. President Joe Biden met with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and reiterated America’s positions on a range of bilateral and regional issues. Both U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan reaffirmed that the United States would make sure that Iran never obtained a nuclear weapon, without clarifying how it would do that. Blinken also met with Gulf Cooperation Council counterparts, and they released a statement outlining positions on Iran, Yemen, Syria, and Israel-Palestinian issues, among other topics. The State Department’s top official on Middle East policy signaled that there is probably a long road ahead in a possible Saudi-Israeli normalization deal, and the U.S. special envoy on Yemen reaffirmed the need for continued diplomacy to end the conflict. This was not unlike other UNGA meetings of years past.

One story that percolated 225 miles southwest of the United Nations in Washington, D.C. could have major implications for U.S. foreign policy overall: the looming threat of a U.S. government shutdown due to budget disputes. To be clear, America has experienced 22 government shutdowns in its history, and they didn’t affect U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East all that much. But at a time when the Biden administration appears poised to move forward on some key initiatives like a Saudi-Israel normalization deal likely requiring legislative action by Congress, America’s overall political gridlock and dysfunction raises an important question: If America’s political leaders can’t agree on basic issues directly related to their responsibilities for governing here at home, how in the world will they build the consensus needed to pass legislation on controversial ones like a defense pact or a civilian nuclear program for Saudi Arabia?

The Biden administration will take its next steps for U.S. Middle East policy, building on its recent efforts, but it may find some new, unexpected hurdles from America’s internal political divisions in trying to advance a broader regional engagement strategy. Even if the United States narrowly avoids its 23rd government shutdown, the internal political dysfunction and discord in America’s politics sends a message to the rest of the world that undercuts its leadership.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

Photo by LEONARDO MUNOZ/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.