Contents:

- Key side meetings involving MENA leaders expected at upcoming G20

- Pakistan has entered a possibly pivotal month

- The US-China tech cold war spreads to the Middle East

- No news on the GERD negotiations is bad news

- Keeping Yemen on the priority list in a crowded US Middle East policy agenda

Key side meetings involving MENA leaders expected at upcoming G20

Paul Salem

President and CEO

-

The upcoming G20 comes days after four MENA countries were invited to join an expanded BRICS, underscoring how many Middle Eastern states are seeking independence from rigid global alignments and looking to expand their opportunities and leverage in multiple global organizations.

-

The absence at the G20 of China’s Xi and Russia’s Putin, on the other hand, indicates that they are prioritizing the emerging BRICS+6 and deprioritizing the G20.

Delegations from the world’s 20 leading economies will meet in New Delhi this weekend. The G20 grouping accounts for 85% of global GDP and 75% of world trade. From the Middle East, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman will attend, as will Turkey’s reelected President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. When it comes to the largest global powers, the United States will be represented by President Joe Biden, but his counterparts from China, Xi Jinping, and Russia, Vladimir Putin, will both be absent.

The G20’s planned agenda includes discussions of global economic and energy issues as well as challenges related to climate change, sustainable development, and debt forgiveness for struggling nations; but often, the bilateral side meetings are as, or more, significant than the talks themselves. With Washington and Riyadh in the midst of intense conversations on a U.S.-brokered Saudi-Israeli normalization deal, there is anticipation of a potential meeting between the U.S. president and the Saudi crown prince to move this agreement forward. Bilaterally as well, Riyadh and Ankara had already agreed — at one of the G20 preparatory meetings — that they will seek to boost trade between their two economies. A side meeting between the once-hostile Erdoğan and Bin Salman is also anticipated; both Saudi Arabia and Turkey have been seeking to rebuild and normalize their relations throughout the Middle East and North Africa region.

The upcoming G20 comes days after the BRICS summit in South Africa, in which four MENA countries — Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt — were invited to join, to create an expanded BRICS+6. It is clear from both summits that key Middle Eastern states are now major players in the international economic arena, are underscoring their independence from rigid global alignments, and are looking to multiply their opportunities and leverage in several global organizations. All this indicates an increasingly multipolar world, especially at the economic and trade levels, even if the U.S. remains the preferred defense and security partner for most of the major MENA countries, minus Iran. The boycott of the G20 by the Chinese and Russian leaders indicates that they are prioritizing the emerging BRICS+6 (and later +more?) and deprioritizing the G20.

For the Middle East, the fact that New Delhi is the host of the upcoming meeting further supplements India’s growing footprint in the region, especially the Gulf. Of course, India has long historical links to the Gulf and much of the workforce in the Gulf Cooperation Council states comes from the subcontinent. But more importantly, India has become a growing technological partner for the MENA region. This was highlighted by the I2U2 grouping (India, Israel, the UAE, and the U.S.) that was formed in 2021 to boost technological and economic cooperation among the four states. And in the run-up to this week’s upcoming summit, India also announced digital cooperation memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with both Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

As G20 leaders (minus Xi and Putin) gather in New Delhi, many in the Middle East will be watching the side meetings among Erdoğan, Bin Salman, and Biden.

Follow on Twitter: @paul_salem

Pakistan has entered a possibly pivotal month

Marvin G. Weinbaum

Director, Afghanistan and Pakistan Studies

-

Several expected developments over the course of September, including the naming of a new chief justice and announcement regarding the date of the elections, should provide greater clarity to Pakistan’s shifting political terrain.

-

Pakistan may soon face a harsh political and economic reckoning because of soaring inflation, declining exports and remittances, rising unemployment, a weakening exchange rate, and a sharp falloff in foreign direct investment.

September may be critical in setting the direction of Pakistan’s political landscape for the months ahead. The country has become accustomed over the last year and a half to a steady stream of scene-changing political developments, most of them relating to the struggle of former Prime Minister Imran Khan to reclaim power. These have resulted in government institutions being pitted against one another, the raising of difficult constitutional issues, and acts of violence. Some of Khan’s actions may have broken new ground in Pakistani politics, while others have served to confirm the country’s politics-as-usual grip of traditional power elites. Still, many issues of consequence remain unresolved. Several expected developments over the course of this month should, however, serve to provide greater clarity to Pakistan’s shifting political terrain.

Both Pakistan’s Supreme Court Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial and President Arif Alvi will complete their tenure of office during September. The two have frequently acted to shield Khan and assisted in his efforts to force early elections. Bandial’s slated replacement, Justice Qazi Faez Isa, could soon reveal how closely the latter is allied with the military by ruling on several pieces of controversial legislation passed by the now dissolved parliament. Alvi, who will remain in office until a new president is named following a forthcoming election, is affiliated with Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. With his decisions, the sitting head of state has done little to disguise his sympathy for the former prime minister and dislike of Khan’s treatment by the political and military establishment.

This month, we should learn when Pakistan is likely to hold its federal and state elections. Constitutionally, they must take place within 90 days following the Aug. 9 dissolution of the National Assembly. It is, however, conceivable that Pakistan’s Electoral Commission will come up with a reason to delay them, very likely by claiming a lack of readiness of new constituency boundaries in accordance with the 2019 Census or by citing some security or economic imperative. Over the coming weeks, we should have an idea of how the weakened mainstream parties will align for the national elections, if anything remains of the previous ruling coalition, and whether the judiciary will clear the way for the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s titular leader, Nawaz Sharif, to return from London and take the party’s helm for the elections.

This month should also give us a good idea of whether Khan can be written off as a player in Pakistan’s politics. There is likely to be judicial action relating to the Toshakhana case, which held Khan in prison last month for selling state assets, and the more serious cyber case, in which he is charged with treason for revealing state secrets — a conviction in the latter could see him locked up for many years. It should also become clearer whether Khan’s party or a stand-in will be allowed to compete even as its leader remains in prison.

September may likewise reveal the likelihood that populist politics will again spill onto the streets. In protest of the continuing imprisonment of Khan, the once powerful (pro-Khan) lawyers’ movement may try to repeat its 2007 success when it was able to restore to office a popular fired chief justice. We should additionally be able to gauge whether ongoing public demonstrations over high inflation could unsettle the interim government as well as the role the far-right Tehreek-e-Labbaik and other fringe groups may be ready to play in mobilizing discontent through its rallies and marches. With the International Monetary Fund (IMF) review slated to occur in late in September, the financial institution will undoubtedly be looking for on-time elections from an interim government that lacks either a popular mandate or evidence of progress toward stabilizing the economy.

A politically distracted interim regime could worsen an economy whose problems may become more acute during September. The country faces strong headwinds from soaring inflation, declining exports and remittances, rising unemployment, a weakening exchange rate, and a sharp falloff in foreign direct investment, from which there is no painless escape. Whether this month or a time not distant, Pakistan may face some harsh political and economic reckoning.

Follow on Twitter: @mgweinbaum

The US-China tech cold war spreads to the Middle East

Mohammed Soliman

Director, Strategic Technologies and Cyber Security Program

-

The U.S. has not blocked AI chip sales to the Middle East, but AI-training chip producers AMD and NVIDIA now face stricter export licensing requirements.

-

This move represents a strategic effort by the U.S. to strengthen its export control measures, concerned with mitigating the risk of these chips being utilized for “military end use” or by a “military end user” in China and Russia.

The United States and China are currently engaged in a broad-ranging technological war, with each country imposing restrictions to safeguard its own critical technology resources. As part of this effort, China has initiated export controls on essential metals required for semiconductor manufacturing. In turn, by leveraging its semiconductor dominance, the U.S. is playing a central role in setting the pace of the global race toward artificial intelligence (AI) by restricting China’s and Russia’s access to AI-training chips, designed to undermine their strategic endeavors.

The U.S. Department of Commerce recently clarified that it had not blocked chip sales to the Middle East, dispelling media rumors of expanded export license requirements for NVIDIA and AMD AI chips beyond China. AMD’s MI300 and NVIDIA’s A100 and H100 chips, renowned for their applications in machine learning and the development of large language models, now face stricter export licensing requirements, however. This move goes beyond China and Russia and represents a strategic effort by the U.S. to strengthen its export control measures. The primary objective is to prevent any potential exploitation of loopholes in these controls, which could circumvent the broader U.S. tech containment strategy.

The concern motivating these restrictions is the necessity to mitigate the risk of these chips being utilized for “military end use” or by a “military end user” in China and Russia. Washington has stressed that this recent development primarily revolves around new licensing requirements rather than constituting an outright export ban on AI chip sales to the Middle East. This messaging approach is geared not only toward maintaining strong bilateral relations but also signaling that there is no fundamental strategic shift in the U.S.’s perception of its regional partners or in their relationships with Moscow and Beijing.

This development serves as yet another example of the delicate balancing act that allies and partners must navigate amidst what has increasingly come to resemble a cold war between the U.S. and China, particularly in technology. As the Gulf region intensifies its digital transformation, these considerations will complicate regional strategies and efforts in this space.

Follow on Twitter: @ThisIsSoliman

No news on the GERD negotiations is bad news

Mirette F. Mabrouk

Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Egypt program

-

The UAE is attempting to broker a deal on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile by promising $20 billion of investment in all three affected riparian countries — Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan — intertwining their mutual interests.

-

The already complex situation has been further complicated by the fact that Sudan is currently mired in an internal conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

The news that the latest round of negotiations on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) last week wrapped up with “no tangible results” would have come as a surprise to only the most optimistic of observers. The talks between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan have dragged on for over a decade with depressing consistency, never achieving any progress. While the issue is complex, it can be boiled down to a few essential facts: The hydroelectric dam, located on the Blue Nile, is the largest on the continent, and Egypt and Sudan both have serious concerns about the effects it might have on them as downstream countries. Their concerns are not identical, but there is enough overlap to keep them on the same side of the negotiating table. While both are worried about water supply, the situation is existential for Egypt, which gets over 95% of its water from the Nile River. Sudan has more access to other water source and, indeed, could benefit from the dam in terms of flood protection and an electricity supply; yet it is deeply worried about security, since the GERD is so close to its borders and could easily affect its own dams. Essentially, both countries have asked for two things: a legally binding agreement over the filling and operation of the dam, which would help secure water in times of drought, and a source of legal arbitration in cases of dispute. Ethiopia has consistently refused both and has taken one unilateral decision after another over the last decade; Egypt and Sudan both insist that these unilateral decisions are in contravention of the 2015 Declaration of Principles, signed by all three countries, while Ethiopia maintains that they are not.

There have been failed attempts at mediation by the United States and the African Union. Currently, the United Arab Emirates is attempting to broker a deal by promising $20 billion of investment in all three countries, intertwining their mutual interests. It’s a solid idea, but the approach has centered on technical talks rather than legally binding agreements, which since;misses the point since all three countries are technically proficient in hydropower and the core differences are political, not technical. Egypt and Sudan have no leverage, and Ethiopia, which has a long track record of regional water hegemony, holds all the cards.

In mid-July, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed met on the sidelines of the Sudan Neighbors Meeting held in Cairo and agreed that a resolution to the GERD would be hammered out in four months’ time. A few days later, Abiy tweeted out that, in consideration for Egypt and Sudan’s concerns, the fourth and latest filling of the dam would take place at the end of August or early September instead of the usual early August. It was a heartening gesture but will hardly suffice to allay fears. While no one knows the impact of the dam on the downstream countries — Ethiopia has refused an Environmental Sustainability Impact Assessment (ESIA), making GERD the only dam in the world of its kind without one — most impartial studies have assessed that under normal rainfall conditions, there is unlikely to be any significant harm to the downstream countries. All bets are off, however, in times of drought, which is what keeps Egypt up at night. Thus, Cairo has consistently, and fruitlessly, held out for a legally binding agreement, which again failed to materialize at this latest round of talks.

The already complex situation has been further complicated by the fact that Sudan is currently mired in an internal conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces, led by Gen. Abdel Fattah Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, headed by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti). Last January, Abiy visited Khartoum for the first time in two years and, notably, was met by Burhan. The visit was followed by an announcement that Sudan and Ethiopia were “aligned and in agreement on all issues regarding” the GERD. A Sudanese agreement on the dam, secured by Abiy and reinforced by the embattled Burhan’s presumed need to shore up regional support behind him, would isolate Egypt at the negotiating table. However, a year earlier, Abiy also met with Hemedti because while Ethiopia and Sudan have made progress on their dispute over the fertile border region of al-Fashqa, it’s possible that Hemedti, formerly the head of the dreaded Janjaweed militia, might attempt to win back this territory. Such an armed incursion by Hemedti’s forces could derail the delicate peace between the two countries and raise the ugly specter of a regional conflict — to say nothing of the further prospects for a trilateral deal on the GERD.

Any agreement on the dam has become an exercise in perpetually kicking the can down the road. Currently, the only hope in sight is the negotiations being shepherded by the UAE, which will have to exercise all its diplomatic and financial charm. The GERD is essentially completed, with two turbines already running and no legally binding regional agreement restricting its operation. The Horn of Africa is suffering a horrific drought; an unprecedented six years of low rainfall, climate change, and destabilized weather patterns indicate that the downstream countries of the Nile face imminent water scarcity. Despite Egypt scrambling on adaptation methods, desalination plants, and a host of other water conservation methods, if the upstream Nile flows are halted or seriously impacted a drought, the consequences might prove catastrophic.

Follow on Twitter: @mmabrouk

Keeping Yemen on the priority list in a crowded US Middle East policy agenda

Brian Katulis

Vice President of Policy

-

Last week, in a State Department ceremony that generated little attention in policy circles, Yemen and the U.S. signed an agreement to extend protections for Yemeni cultural heritage under threat due to the country’s ongoing conflict.

-

The human security situation remains dire for millions of people, but Yemen doesn’t seem to garner as much attention as it did just a few years ago in Washington. This agreement is a reminder of why it’s important to not let the resolution of Yemen’s conflict fall lower on the U.S. list of priorities in the Middle East.

Remember Yemen? The country was cause célèbre in certain policy and political circles in Washington, particularly during the Trump administration, as a brutal conflict claimed thousands of civilian lives and a chorus of voices called for “ending the war.” Some of those who took part in the advocacy efforts during that period were former Obama administration officials who wrote a mea culpa letter about Yemen in 2018, and a number of them went on to join the Biden administration in 2021.

When President Joe Biden came into office, he put forward several priorities in the Middle East in an interim national security guidance and an early speech that spotlighted efforts to help Yemenis bring their deadly conflict to an end. He appointed a seasoned career diplomat, Tim Lenderking, as special envoy for Yemen, who has been engaged in long-term diplomatic efforts to help the people of Yemen live in peace. It’s those long-term, patient diplomatic efforts, rather than the heated and often-politicized debates in Congress, that will likely prove more essential to advance stability in places like Yemen.

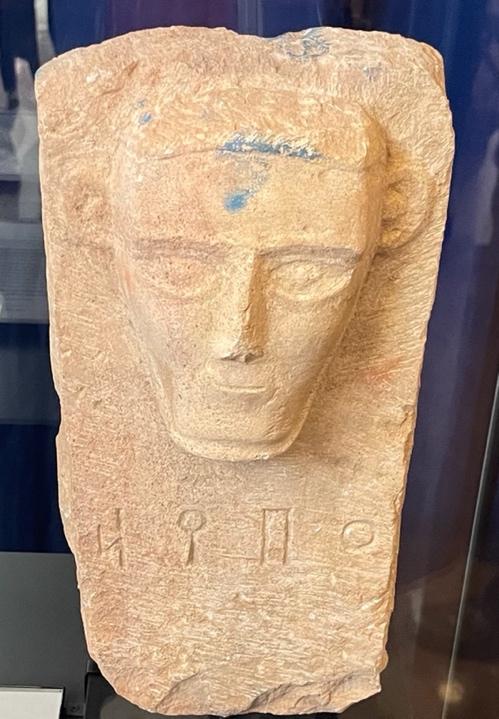

Last week, in a State Department ceremony that generated little attention in Washington, D.C. policy circles, Yemen’s ambassador to the United States signed an agreement with U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Lee Satterfield to extend protections for Yemeni cultural heritage items under threat due to the country’s ongoing conflict. This agreement will remind Americans that “there’s much more than war and famine in Yemen,” Lenderking noted to the audience present at the signing ceremony. In taking small but important steps together to protect the country’s rich cultural heritage, the Yemeni government and State Department are sending the message that Yemen and its people shouldn’t just be used as props in U.S. foreign policy debates, as they often have been in the past. The initiative also builds on previous steps to repatriate and protect Yemen’s rich cultural, artistic, and historical artifacts.

The situation in Yemen remains unstable, as the United Nations envoy recently warned; and it’s been nearly a year since the Houthis failed to renew a cease-fire agreement. The human security situation remains dire for millions of people. Yet Yemen doesn’t seem to garner as much attention as it did just a few years ago in the U.S. policy debate.

As the Biden administration seeks to stay on top of major foreign policy issues from the Russo-Ukrainian war to China and works to engage Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the Palestinians in a possible deal to advance regional integration and normalization, it should keep the people of Yemen on the agenda in broader efforts to support stability and de-escalation in the Middle East. This small agreement between the United States and Yemen on one narrow slice of cultural cooperation serves as a reminder of why it’s important to not let the resolution of Yemen’s conflict fall lower on the list of priorities in America’s crowded Middle East policy agenda.

Follow on Twitter: @Katulis

Photo by Elke Scholiers/Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.