Originally posted December, 2010

It is a lofty ambition to try to create a legacy of understanding and closer relations between cultures, but indeed it is at the heart of everything The Istanbul Center of Atlanta strives to accomplish for the southeastern United States and beyond. “We seek above all to proactively contribute to solving educational, cultural, environmental, social and humanitarian issues. The Center does this by creating opportunities for children and adults to engage in dialogue through education, culture and humanitarian works.”[1] The Center provides learning opportunities for all ages in several disciplines, including the Turkish language, working with local, regional, national, and international organizations.[2] The annual regional art and essay contest — the subject of this essay — exemplifies this work.

In 2008, the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations Secretariat in New York became one of the sponsors for the art and essay contest. The speech written by President Jorge Sampaio and delivered by Dr. Thomas Uthup of the UN Alliance at the 2009–2010 awards ceremony conveys eloquently the alignment of cross-cultural goals:

Ladies and gentlemen, globalization and migration brings together different cultural communities who may previously not have had much interaction with each other. Interaction of different groups can be a source of friction and often of conflict. But cultural diversity can also result in cross-fertilization and success stories of people interacting in mutual respect and harmony. Cultural diversity can spark innovation, stimulate creativity, and boost the economy. Indeed Atlanta, Georgia, and the United States have seen this first-hand.

The Istanbul Center’s efforts to promote better understanding and closer relations between the Turkish, American, and other communities of Atlanta and the southeastern United States are inspiring in this regard.

In my mind, the value of the Istanbul Center’s annual Art and Essay Contest is in stimulating young people to think positively and creatively about cultural diversity and the bridging of cultures.[3]

As an educator fully invested in promoting cross-cultural harmony, I welcomed these words. From the moment I walked in the doors of The Istanbul Center of Atlanta, I determined that this was a very unique organization. Along with 30 other Georgia professors who had attended faculty workshops on the Middle East in the fall of 2004,[4] I was invited at the end of the workshop to a Ramadan Iftar at The Istanbul Center’s Norcross location. We were all treated with the most gracious attention, and I soon found myself supporting some of their Turkish students on the Kennesaw State University campus through the self-styled, “Intercultural Dialogue and Empathy Association” (IDEA) student group. Eventually, I was invited to serve as a judge for an art and essay contest that The Istanbul Center hoped to launch in 2007. The first run of the contest was fairly awkward — too little experience with such things resulted in few rules by which to operate and few entries to judge. Since then, however, the program has grown by leaps and bounds, much through guidance from art educators such as Jeanette Wachtman, Debi West, and myself, as well as the competent and dedicated staff of The Istanbul Center.

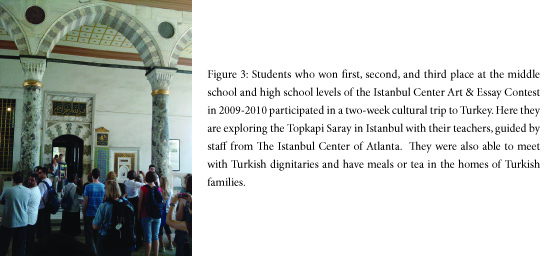

Through the years I have increased my activity with The Istanbul Center, including a position on their advisory board, and have continued my role of “head” art judge for what has grown into a regional secondary school contest. Among the many prizes awarded to the winners are trips to Turkey through The Istanbul Center’s travel program.[5]

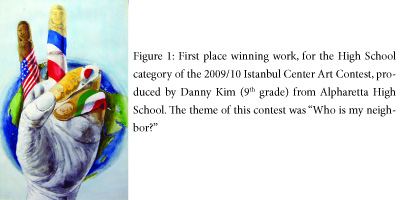

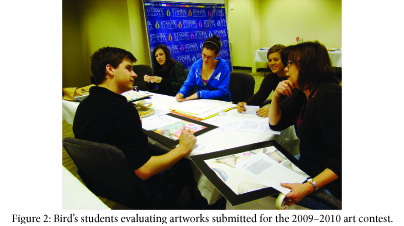

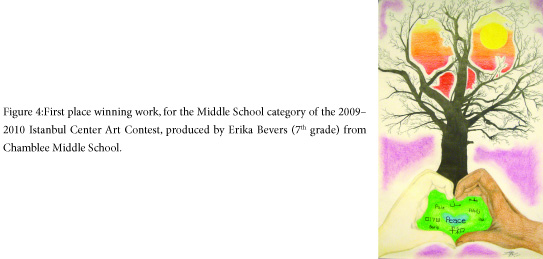

Over the past year, I began involving my own art education students[6] in the adjudication process of the Istanbul Center’s art contest. My students served as preliminary judges, using a rubric created for this purpose.[7] At this point in their training, these students were still learning about secondary school graphic development, as well as how to properly gauge success in artworks using a formal grading system. Using a rubric at this preliminary stage of judging was helpful to the students as they reviewed and then ranked artworks. There was a practical purpose for the initial “hierarchical” rating, as it helped to cull many of the over 1,000 works submitted to the 2009–2010 art contest. Nevertheless, using rubrics for art contests is somewhat heretical in art adjudication circles. There is a tendency to use subjective, but more reliable methods of triangulation — combining several reviewers’ informed critical opinions when determining value in artworks. The students’ quantified rankings were met with suspicion by the faculty judges, who in truth were the “real” decision makers for our final slate of winners.

I asked an art education colleague and program evaluator, Dr. April Munson, to examine the art judging process this year. This, the fourth year of the contest, seemed an appropriate window for assessing how effectively the art adjudication proceeded. While I regret that the faculty judges found this process unnerving, I do see clear benefits to my art education students regarding several factors. First of all, they were able to provide a constructive service to an active community organization that craves young partners who are willing to work toward a common good, in this case helping to identify ideas that provide “out-of-the-box” solutions/opinions on this world that we all share. For many of my art education students, it was their first contact with people from Turkey, or even Muslims in general. Just being at The Istanbul Center for two sessions of classes gave the students an idea of Turkish gentility and enthusiasm for building international relationships. They also had an opportunity to see how artworks can be evaluated according to formal directives. As more and more “objective” evaluation criteria are used in our schools to assess artworks (sadly, to validate the importance of the arts in our schools), I can be certain that my students can administer rigorous assessment according to well defined parameters when needed.

I asked an art education colleague and program evaluator, Dr. April Munson, to examine the art judging process this year. This, the fourth year of the contest, seemed an appropriate window for assessing how effectively the art adjudication proceeded. While I regret that the faculty judges found this process unnerving, I do see clear benefits to my art education students regarding several factors. First of all, they were able to provide a constructive service to an active community organization that craves young partners who are willing to work toward a common good, in this case helping to identify ideas that provide “out-of-the-box” solutions/opinions on this world that we all share. For many of my art education students, it was their first contact with people from Turkey, or even Muslims in general. Just being at The Istanbul Center for two sessions of classes gave the students an idea of Turkish gentility and enthusiasm for building international relationships. They also had an opportunity to see how artworks can be evaluated according to formal directives. As more and more “objective” evaluation criteria are used in our schools to assess artworks (sadly, to validate the importance of the arts in our schools), I can be certain that my students can administer rigorous assessment according to well defined parameters when needed.

Ultimately, Dr. Munson recognized that the end product, effective judging, was achieved: “The final judging process occurred with little discrepancy among judges. The top ten pieces were ranked after conversation and adequate assessment time.” Their findings for the top group were consistent with the student-led assessment. For me, this speaks to the internal validity of our adjudication findings. The winning selections will be on display at the United Nations Building in the fall of 2010, and are currently linked to the Alliance of Civilizations’ website through an article on The Istanbul Center’s annual contest.8

Several of the people involved in the contest are in the process of preparing a monograph about the 2009–2010 experience. One of them is Cassandra Whitehead, the Assistant to the Istanbul Center Director, Tarik Celik, and Coordinator of the student/teacher/superintendent trips to Turkey. Among the many valuable things that Cassandra contributes to the monograph are the results of a series of evaluations conducted with the contest’s travelers following their trek through the country. While they are all very rich comments, I have selected an excerpt from the text of one of the students, Jenni Paek, which encapsulates the experiences of these young people as a result of their initial encounter with this part of the world:

Later, throughout the trip, is when I discovered the trip’s sentimental and cultural impact onto my life and it gave me the sudden realization that I had won something more than just a trip. We were embarking on a life-changing journey … to change our perspectives of people different than ourselves and to learn of a culture by stepping right into the middle of its country. I believe that I had only an idea in which throughout the years, the news and media had constructed in my mind, of what I was to expect going into a Middle Eastern country. I was dumbfounded each and every day of our trip of how much my perspectives were severely misguided.[8]

At many of the award ceremonies for this contest, I frequently share my opinion that we need this kind of problem-solving and youthful optimism in order to foster mutual understanding between people of different cultures. The Istanbul Center’s contest models successful critical thinking in the arts — an excellent vehicle for transforming attitudes and exploring solutions to our contemporary problems.

[1]. The Istanbul Center of Atlanta is a 501(c) 3 non-profit, non-governmental, and non-partisan organization that was established in 2002. This quote is from the Istanbul Center website, available at www.istanbulcenter.org/ .

[2]. A description of the Istanbul Center Art and Essay Contest for 2009–2010, including a full list of winners for the art and essay contest, www.istanbulcenter.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=371….

[3]. For the complete text of the speech, see www.unaoc.org/content/view/468/200/lang,english/ .

[4]. This workshop series, Teaching the Middle East, is offered annually through the Georgia State University Middle East Institute, and information is available through their website at www.cas.gsu.edu/dept/mec/.

[5]. For information regarding the Istanbul Center’s “Dialogue” trips to Turkey, see www.istanbulcenter.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layou….

[6]. The Kennesaw State University students that participated in the first round of judging for the 2009–2010 art contest were enrolled in my Art Education course, ARED 3304 Teaching Art History, Criticism, and Aesthetics. At the time of the judging, we were looking at how artworks are valued and how good evaluation is determined by a set of criteria that is shared with artist participants before works are created, and then is used again to steer “objective” assessments. This type of art assessment is more helpful in a classroom for art teachers than for judging art contests.

[7]. The art standards and rubric for last year’s theme, “Who is my Neighbor?” are essentially the same for this year’s theme of “Empathy: Walking in Another’s Shoes.” See www.artandessaycontest.com/ArtC.aspx.

[8]. This passage was written by Jenni Paek, the 2009 2nd Place Winner of the Istanbul Center’s art contest for the High School Division. Jenni was a student from North Gwinnett High School in Suwannee, Georgia.

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.