Originally posted June 2011

If there is a Horizontal Line that runs from the MAP off your body straight through the Land shooting up right through my heart Will this Horizontal Line when asked know how to find Where you end where I begin

— Tori Amos[1]

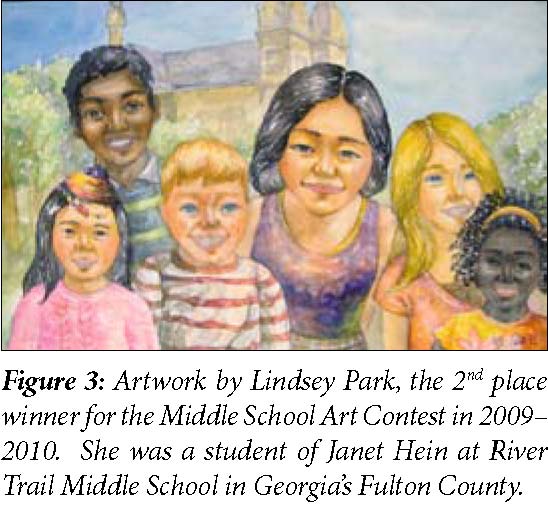

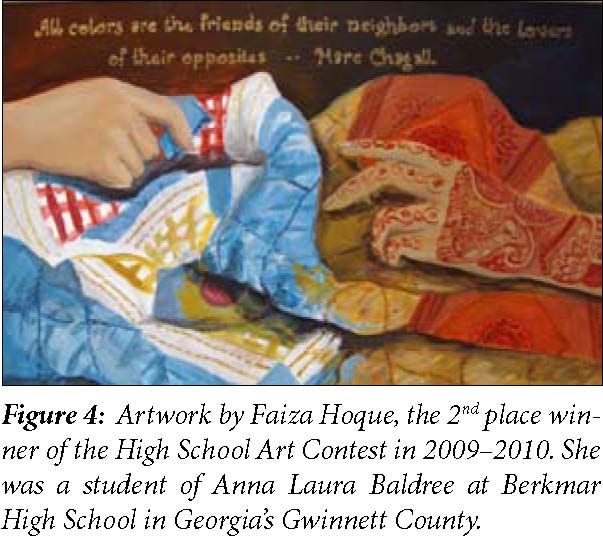

For the past two years, I have accompanied top-winning students and teachers to Turkey on behalf of the Istanbul Center. The Contest’s aim is to broaden the horizons of all students and teachers by promoting inter-cultural relations, understanding, dialogue, tolerance, and the awareness of one’s place in the now “glocal” civic society (glocal — “global” plus “local” — is a post-modern catchphrase that illustrates the increasing interconnectedness of international commerce, politics, and people).

The prize of being able to go to Turkey is not meant to be a vacation. It is an extension of the hard work winners have already put into each piece that eventually served as their chance to travel. The jam-packed trip is also an extension of the high caliber of understanding top winners already exhibit by virtue of their placement of 1st, 2nd, or 3rd. The schedule of the prized trip to Turkey is demanding. Most days start at the latest by 9:00 am, including having had breakfast independently at the hotel. Students and teachers are expected to hit the ground running until sometimes after midnight, especially if a planned host family dinner goes well. To be able to properly interact with local Turkish hosts, evening dinner programs encompass three to four hours of introductions and engaging conversation, exchanging gifts, and of course, eating at least a three-course meal, which does not include courses of Turkish tea, coffee, dessert, and fruit afterwards. Phew! Anyone being obliged to this sort of schedule deserves, indeed, to be an ambassador.

Americans are habitually used to big endeavors being planned out in advance — at least several months in advance, especially for a trip hosting minors abroad. In Turkey, it is normal to plan major events within a short period of time, sometimes no more than two weeks in advance, depending on the endeavor. The itinerary may say we’re going to Miniaturk, but if the Superintendent of Istanbul tells our boss (Tarik Celik, Executive Director of Istanbul Center) that he can meet with us, we will attend. No questions asked. It is a bit difficult to describe this attitude towards planning to American teachers and parents beforehand as well as when circumstances change, because the purpose of the trip abroad is not just for Americans to see as much of Turkey as possible, but for Turkish people to get to know more Americans. Real Americans, that is. Not the kind you see on television and Hollywood.

Americans are habitually used to big endeavors being planned out in advance — at least several months in advance, especially for a trip hosting minors abroad. In Turkey, it is normal to plan major events within a short period of time, sometimes no more than two weeks in advance, depending on the endeavor. The itinerary may say we’re going to Miniaturk, but if the Superintendent of Istanbul tells our boss (Tarik Celik, Executive Director of Istanbul Center) that he can meet with us, we will attend. No questions asked. It is a bit difficult to describe this attitude towards planning to American teachers and parents beforehand as well as when circumstances change, because the purpose of the trip abroad is not just for Americans to see as much of Turkey as possible, but for Turkish people to get to know more Americans. Real Americans, that is. Not the kind you see on television and Hollywood.

Sliding between the Turkish and American mindsets of planning and communication is tricky. Each culture has its own system of thought governed by expectations, rules, and behaviors that dictate one’s actions and reactions. In psychological terms, many identify this system of thought as a schema, a term in psychology that has evolved from the works of Jean Piaget, Sir Frederic Bartlett, and R.C. Anderson. The American side of me wants the schedule to be certain. The Turkish side of me takes a rather laissez-faire attitude and knows intuitively well that everything will work out. I acquired this faith over time in being the only American working at the Istanbul Center as we would work diligently to create content-rich programming. It took me a long time to understand that what I had interpreted as a laissez-faire attitude was actually a deeply profound trust in doing your best, yet allowing the universe to take its course.

Students and teachers that I accompany on the trip are challenged to incorporate new schemata, or systems of thought and ways of seeing, into their body of knowledge about the world. These are primarily in relation to Turkish people, Muslims generally, and even the traveler’s own cultural and spiritual awareness. Students and teachers are placed into unfamiliar surroundings, albeit with guides, where their schemata for functioning within their own societies back home are used to decipher how to function abroad. Their mental acuity for processing stimuli from their environment is altered, and indeed made more sophisticated by the psychological and sensory challenges of a highly foreign environment. Each experience a person has provides a psychological imprint into that person’s memory to be drawn up again when needed by the individual to process one’s surroundings and act appropriately. As many of the students and teachers who joined me on the trip knew relatively nothing about Turkey, they had no idea what to expect. Their expectations were in fact that Turkey was a country consisting of purely a desert climate, which, to most Americans, usually means a country that is synonymous with the Middle East, terrorism, repression of women, and Muslim extremists.

Students and teachers that I accompany on the trip are challenged to incorporate new schemata, or systems of thought and ways of seeing, into their body of knowledge about the world. These are primarily in relation to Turkish people, Muslims generally, and even the traveler’s own cultural and spiritual awareness. Students and teachers are placed into unfamiliar surroundings, albeit with guides, where their schemata for functioning within their own societies back home are used to decipher how to function abroad. Their mental acuity for processing stimuli from their environment is altered, and indeed made more sophisticated by the psychological and sensory challenges of a highly foreign environment. Each experience a person has provides a psychological imprint into that person’s memory to be drawn up again when needed by the individual to process one’s surroundings and act appropriately. As many of the students and teachers who joined me on the trip knew relatively nothing about Turkey, they had no idea what to expect. Their expectations were in fact that Turkey was a country consisting of purely a desert climate, which, to most Americans, usually means a country that is synonymous with the Middle East, terrorism, repression of women, and Muslim extremists.

In my work with the contest, much of my personal fulfillment comes in watching students and teachers react as they experience Turkey’s hospitality and its surprising, modern dynamics. They venture to one of the oldest places on the planet and always think that the day we just completed was their favorite day of the trip — until the next day — when they have changed their minds and decided that: “No, this day is my favorite day!” Students and teachers who participate bear witness to the inability to express themselves in words after returning to the United States. The flowering experience of traveling to a new land with drastically different ways of doing things than one’s home country matures and sharpens students’ and teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, and critical thinking. They will never watch or listen to a newscast in the same fashion because they know that it might not all be true.

I always ask the same open-ended question: “So what do you think about Turkey?” The tie for first place goes to 1) the deep warmness and hospitality of the Turkish people and 2) how impressively modern Turkey is compared with what our guests had been taught back home. A close second is how similar Turkish families are to American families, namely, how important family life is to Turks, just as it is to Americans. In addition to this realization, I am not able to think of any one of our guests telling me that they would not want to come back to Turkey again, whether it is to take a vacation, teach or continue exploring. A second part of my personal fulfillment comes when I read the evaluations of the trip.[2]

I always ask the same open-ended question: “So what do you think about Turkey?” The tie for first place goes to 1) the deep warmness and hospitality of the Turkish people and 2) how impressively modern Turkey is compared with what our guests had been taught back home. A close second is how similar Turkish families are to American families, namely, how important family life is to Turks, just as it is to Americans. In addition to this realization, I am not able to think of any one of our guests telling me that they would not want to come back to Turkey again, whether it is to take a vacation, teach or continue exploring. A second part of my personal fulfillment comes when I read the evaluations of the trip.[2]

Feedback: Later, throughout the trip, is when I discovered the trip’s sentimental and cultural impact onto my life and it gave me the sudden realization that I had won something more than just a trip … We were embarking to a life changing journey to change our perspectives of people different than ourselves and to learn of a culture by stepping right into the middle of its country … I believe that I had only an idea in which throughout the years, the news and media had constructed in my mind, of what I was to expect going into a Middle Eastern country. I was dumbfounded each and every day of our trip of how much my perspectives were severely misguided.

— Jenni Paek, 2009 2nd Place Winner, Art High School Category, North Gwinnett High School, Suwannee, GA.

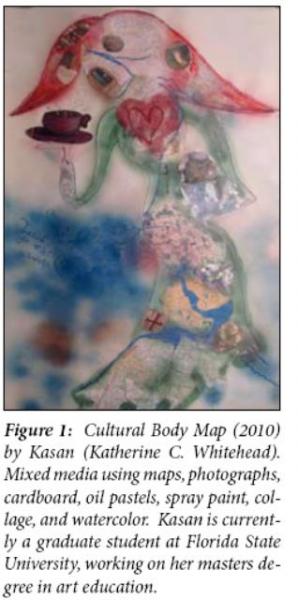

Jenni’s account of the “sentimental and cultural impact” in her life exhibits the profound changes that occur for each participant of the trip. Her “life-changing journey” is quintessential of sentiments felt by many, if not all, of the contest’s winners as they return from Turkey. Jenni will now think twice in meeting someone from a foreign land. She will also think critically about anything she may hear about a foreign country or people. In addition, her own appreciation for where she comes from is also embellished. Jenni’s growth exemplifies how her ‘cultural body map’ has grown. She has added layers of experience that have allowed her to think much deeper about her world than most young people. She has morphed into a mature, young woman. Tiffany Simmons’ offers a very mature reflection also indicative of her growth as a person.

Nicole Sikes’ “life-altering experience” is something that can never be taken away from her because the experiences she had in Turkey added layers of new thoughts, ideas, and perceptions unbeknownst to her before. Additionally, her own perception of her native American culture is now more sophisticated.

Nicole Sikes’ “life-altering experience” is something that can never be taken away from her because the experiences she had in Turkey added layers of new thoughts, ideas, and perceptions unbeknownst to her before. Additionally, her own perception of her native American culture is now more sophisticated.

Olivia Stehr, like her compatriots, also has a deeper understanding of the world around her. As she continues to mature as a young adult, her approach to solving problems with people will be different than if she had not participated in the trip to Turkey. Further, her own view of humanity is refined because she learned that she is “more similar to the Turkish people that I had once believed.”

Melissa Kuester, 1st Place Winner in the Essay Middle School Category from Trickum Middle School, could not help but cry at the airport as we waited in line to check in our travelers for their flight back home. Her tearful, emotional reaction to leaving Turkey marked how strongly she felt about her love of the country and its people. It also showed the depth at which she felt affected.

Half-way around the world, American students and teachers are learning life lessons about growth, perception, belief systems, and societies very different from their own. They also learn how large of a role culture and stereotypes play a part in their own schemata. The cognitive learning that I witnessed this past June for the second year in a row still excites me. Each June, the previous year’s work for the Art & Essay Contest culminates when I see not only the maturation of winning students, but also the making of life-long friends.

Half-way around the world, American students and teachers are learning life lessons about growth, perception, belief systems, and societies very different from their own. They also learn how large of a role culture and stereotypes play a part in their own schemata. The cognitive learning that I witnessed this past June for the second year in a row still excites me. Each June, the previous year’s work for the Art & Essay Contest culminates when I see not only the maturation of winning students, but also the making of life-long friends.

The message of the Istanbul Center Art and Essay Contest is substantial, so too is the impact the contest presents to its participants and the community at large. Students and teachers who visit Turkey continue to talk about their remarkable encounters. These students and teachers will view neither themselves nor others the way they did before visiting Turkey. Each individual’s ‘cultural body map’, as well as schemata, have changed via extensive, life-changing occurrences abroad, adding profound layers of knowledge, depth, sophistication, and fond memories of a distant land and its people.

[1].Amos, T. ( 2002) “Your Cloud.” Scarlet’s Walk. Sony Music Entertainment, Inc.

[2]. Websites of interest, responding to the students’ travel experiences: Travel Blog of the 2010 Winners’ Trip to Turkey, http://artessayturkiye2010.blogspot.com/ and a U.N. photo essay, https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=explorer&chrome=true&srcid=0B3sO….

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.