Introduction

The past year has seen a trend toward normalization with the Assad regime, accompanied by a push by some nations to force or coerce displaced Syrians to return — or deny them asylum outright. In response, a flurry of reports have been released in recent months by advocacy groups, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, that highlight the abuses that innocent Syrians risk facing upon return. These reports focus on the stories of survivors and their loved ones as they come into contact with the Government of Syria (GoS) and its security apparatus upon return, and have qualitatively demonstrated that despite a reduction in military operations, arbitrary arrest, revocation of rights, enforced disappearance, torture, extortion, rape, and death still abound and have not been eliminated from the regime’s playbook.

These advocacy reports serve as a valuable contribution to the bank of available information. However, critics claim that a focus on isolated incidents solely within one control area, specifically those that are held by the GoS, cannot be extrapolated to reflect larger trends in Syria. As a result, a claim can be made that other parts of the country, for instance the northeast, are safe for return on the basis that there are ongoing stabilization projects, a U.S. presence, and fewer military incursions. Some also argue that northwest Syria is safe for the return of refugees from Turkey, given the latter’s control of the area. These are not fair assessments, however; they do reflect how the lack of information and testimonies from Syrians themselves misguides policymakers, leading to return policies built upon flawed baselines. The presumption that Syria is now safe for return is often motivated by political expediency and a false equivalency between “safety” and reduced military operations in a particular area, rather than an in-depth understanding of conditions on the ground and the challenges that returnees face. These challenges are often invisible in nature — intentionally or otherwise — due to the way that the Assad family has ensured its continuing rule for decades; enforced disappearances and torture are and have long been primary tools used to terrorize the Syrian people, and thereby solidify regime control by silencing victims and preventing their experiences from coming to light. This results in an information vacuum and widespread self-censorship throughout the country, especially today.

With the GoS and other actors obstructing the U.N. from implementing independent and robust monitoring mechanisms throughout the whole of Syria, data regarding the frequency of violations experienced by returnees is thus incomplete. Within this environment of fear, protection monitoring is severely hindered, making the regularity of violations against returnees notoriously difficult to establish. Many returnees simply refuse to participate in surveys, while others do not feel comfortable answering some of the questions. Moreover, researchers and monitors have no access to Syria’s highly complex prison system, which is necessary to assess the situation and produce a clear picture of what is happening. Absent international cooperation, Syrian civil society is thus forced to take up the lengthy and painstaking process of collecting valid data, exposing themselves to incredible risk in the process.

In an attempt to close the gap, and with pressures for return increasing, the Voices for Displaced Syrians (VDSF) and the Operations and Policy Center (OPC) undertook a first-of-its-kind research project to establish the minimum frequency and types of violations experienced by returnees throughout the whole of Syria, informed by their perspectives and experiences. Despite the known difficulties, the report aimed at obtaining an understanding of at least the minimum frequency with which violations occur, which is a critical step in discussions about return. Indeed, if the safety of returnees cannot be ensured at that baseline, then the true regularity at which violations occur likely suggests even more dismal safety prospects for the average Syrian who has fled. This should enable policymakers to make more informed decisions around return to Syria.

The project took a systemic approach and surveyed 300 returnees across all four control areas in the country, assessing the findings against the U.N.’s 22 Protection Thresholds that must be met before mass voluntary returns can be initiated. The final report details violations on multiple scales including physical, psychosocial, material, and legal safety. Moreover, the project distinguishes itself from previous research by defining returnees not only as refugees who have returned to Syria from abroad, but also internally displaced Syrians who return to their area of origin from a different control area. The sample was split equally between returnees from abroad and from within the country, which allowed the research to capture greater nuance on the challenges internal returnees experience as well.

As expected, many Syrians surveyed did not feel comfortable providing details about sensitive issues that might lead them to become targeted, meaning that frequency and severity of incidents are undoubtedly undercounted. Therefore surveys alone remain an imperfect tool for getting the clearest picture of reality, especially in war zones where random sampling is difficult. Despite these limitations, surveys are valuable in that they improve our understanding to the extent possible under the circumstances. The lower baseline that has been established through this report is valuable in that it demonstrates that previously documented violations are far from isolated incidents and are not limited to GoS-held areas, which means safety for returnees cannot be guaranteed. The report also acts as a blueprint for future monitoring initiatives and an example of how to gain a more nuanced understanding of individual experiences that are hard to capture in an environment of severe repression.

Return experiences

Notably, within the whole returnee sample, a full 41% reported that they did not return to Syria voluntarily. Meanwhile, of those who stated that they did, 42% of them said that push factors played a larger role in their decision; these factors included a poor living situation in host areas, an unstable security situation, and the inability to continue studying. This means that a large portion of those who self-report their return as voluntary still do not meet the U.N.’s definition of voluntary return, having been driven through various forms of coercion or force from their place of displacement.

Moreover, 24% of returnees who cited pull (rather than push) factors as a primary motivation for their return were pulled by family reunification. The majority of this subsample were returnees from abroad; this suggests that restrictive policies around family reunification in host countries are a major force behind Syrians’ decision to go back, potentially acting as a form of coercion.

“The living situation in Syria is very difficult, and if it wasn't for my family pressuring me, I would have never returned.”

— Returnee from the EU to Damascus

“Life without our loved ones is intolerable. There is no point in being in heaven without your people.”

— Returnee from Germany to Jaramana

At the whole-of-Syria level, regrets about return were split, with just over half of returnees (52%) feeling confident about their decision, and the other half either regretting it entirely or expressing doubts and uncertainties.

Physical safety is at risk

Returnees were asked about their experiences with violence and harassment. At the whole-of-Syria level, 17% reported they or a loved one faced arbitrary arrest or detention during the past year alone, despite the reduction in armed hostilities and Covid-19 lockdowns during this period. Moreover, 11% reported that they or a loved one experienced physical violence or harm, with an additional 7% preferring not to answer.

Concerns about physical safety were more frequent in areas under GoS control than elsewhere, especially for internal returnees, who reported being targeted at a far higher rate than returnees from abroad. Indeed, nearly half (46%) of internal returnees in GoS areas reported that they or a loved one experienced arbitrary arrest or detention over the last year (compared to 18% from abroad); while 30% reported they or a loved one endured physical violence or harm (compared to 18% from abroad). This highlights that there is an urgent need for protection monitoring mechanisms not only for refugee returnees, but also for internal returnees.

Moreover, 27% of returnees across all control areas reported that they or someone close to them faced persecution due to their place of origin, for having left Syria illegally, or for lodging an asylum claim abroad. Again, these percentages were highest in GoS areas, at nearly 50%, showing how the Assad regime continues to target dissidents.

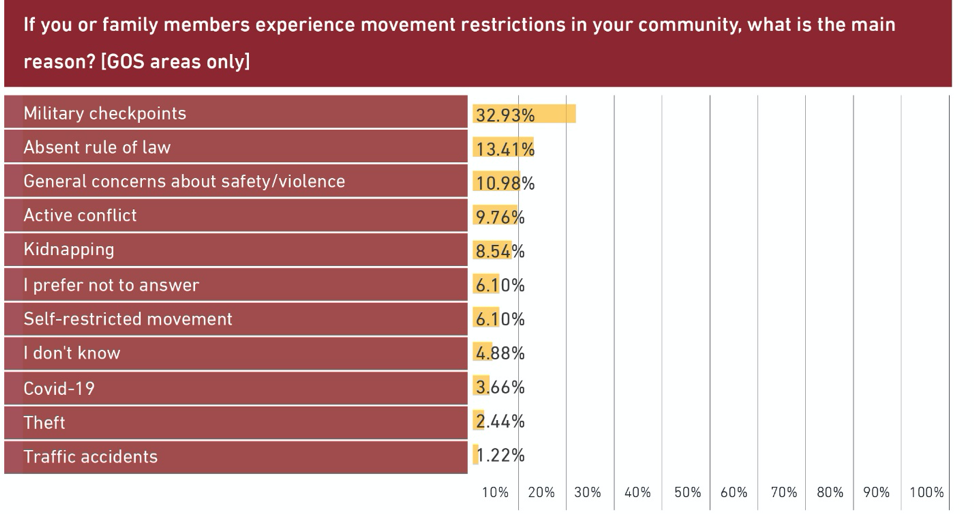

Finally, despite a reduction in active conflict, returnees reported severe restrictions on movement across the country, for a variety of reasons, but especially those related to Covid-19. In GoS areas, the reasons provided were particularly troubling. As detailed in the graph below, Covid-19 restrictions played a far smaller role than concerns around military checkpoints, kidnappings, violence, and conflict.

Finally, reports of active military recruitment came from all control areas, but in especially high numbers in GoS and Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) territories.

Return where?

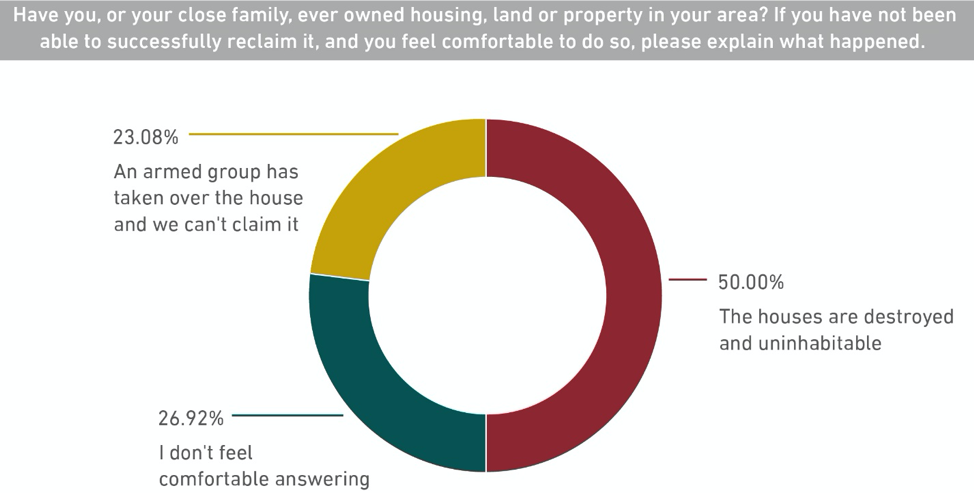

Housing, land, and property (HLP) rights are another issue of importance for Syrian returnees. The survey found that, at the whole-of-Syria level, 11% of returnees who owned HLP in their area have been unable to reclaim it, with an additional 6% preferring not to answer. The main reasons cited were destruction of the home, or the home being overtaken by armed groups, each in frequencies detailed below.

In GoS areas specifically, 24% of returnees who confirmed that they owned HLP in the area said they have been unable to reclaim it, with an additional 14% preferring not to answer. This is likely facilitated by HLP laws aimed at punishing dissidents, for instance Law No. 10, which was issued in 2018. As of May 2020, at least 50,000 Syrians have lost their homes due to this legislation.

In terms of reclaiming property, it is also important to note that there are large differences between returnees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). IDPs report greater difficulty in reclaiming their property, and in much higher frequency, than returnees, which poses a significant obstacle to their ability to return. This is not surprising, as loss of HLP is a primary driver behind protracted displacement. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the data here is unlikely to reflect the average situation for most displaced Syrians, as the research sample only included Syrians who have already returned — in other words, those who had a home to return to. The prevalence of Syrian refugees and IDPs who are unable to reclaim their HLP is therefore likely to be higher.

Documentation and protection

In terms of documentation, at least 32% of returnees reported that they or a loved one have experienced at least some difficulty in obtaining documentation for children born outside Syria, foreign spouses, or others. When asked to provide details, returnees at the whole-of-Syria level reported that they struggled to obtain passports (21%), register children born outside of Syria (21%), and register a marriage (16%). One-fourth of returnees detailed that they or family members were missing official (Syrian government-issued) documentation, placing them at risk of statelessness — an issue that could become a major disaster in the future if left unaddressed.

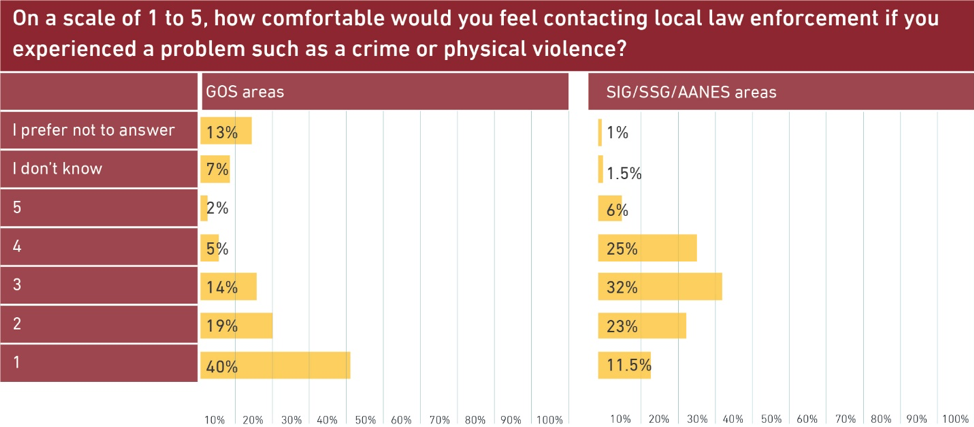

Moreover, few returnees confirmed the presence of justice and law enforcement channels to help them sufficiently address violations they have suffered in their communities; a full 27% of returnees stated that these channels do not exist at all, while 15% stated that they do. Narrowing in on GoS areas specifically, returnees reported that these channels were virtually nonexistent (only 3% overall and 0% in Damascus City said they exist). For comparison, this number stood at around 20% in Syrian Interim Government/Syrian Salvation Government (SIG/SSG) and AANES territories.

Also concerning is that even where law enforcement channels may exist, levels of comfort and trust in them may not. The graph below demonstrates that returnees across all of Syria would have a generally low level of comfort in contacting local law enforcement, were they to be victims of a crime or physical violence.

The big picture

The 22 Protection Thresholds established by the U.N. are currently the main indicators being used to justify a move into large-scale and facilitated returns. Given the report's findings, we assessed that 16 thresholds are currently considered “not met,” while four can be considered “partially met,” and two are too unclear to make a well-informed determination, requiring further research. In other words, none of the thresholds were considered sufficiently met, which is to say that conditions are not suitable to allow the facilitated return of Syrian refugees and IDPs. This holds true across all areas of Syria, but especially so in areas held by the Assad regime, where most of the recent push for return by host countries has been happening.

Indeed, the data indicates that policies aiming to push Syrians to return prematurely are not based on evidence, as even the lower baseline shows. Recent efforts to normalize relations with the GoS are therefore troubling, as data indicates that its treatment of dissidents and returnees, the root cause of mass displacement in Syria, have not changed and show no signs of doing so. Stakeholders should take note that recent policies around returns are thus not grounded in evidence but in an effort by the GoS and other parties to the conflict to foster a carefully constructed illusion of safety and stability in the country — and thereby, legitimacy in the global arena — to fulfill their own political ends. As a result, innocent Syrians are now doubly harmed not only by a regime that continues to pursue them through inhumane and covert judicial, political, and security means, but also by international policies enabling these trends to continue unabated, by perpetuating and legitimizing the false image of safety being painted.

Recommendations

In conclusion, it is important to reiterate that the dangers of premature return throughout the whole of Syria are very serious. All host countries should end the use of force, coercion, and incentives to drive Syrians back to Syria before it is safe, especially while there is a near complete absence of monitoring and safeguarding measures. The fundamental principle of non-refoulement as established in the 1951 Refugee Convention should hold firm at the core of all stakeholder policies, and the categorization of any area as “safe” should not be determined solely on the basis of whether or not military operations are being carried out there. Syrians are subject to many types of risks and violations, as our research shows; these can be both explicit and implicit, and based on varied factors including political affiliations, area of origin, religion, gender, tribe, and more.

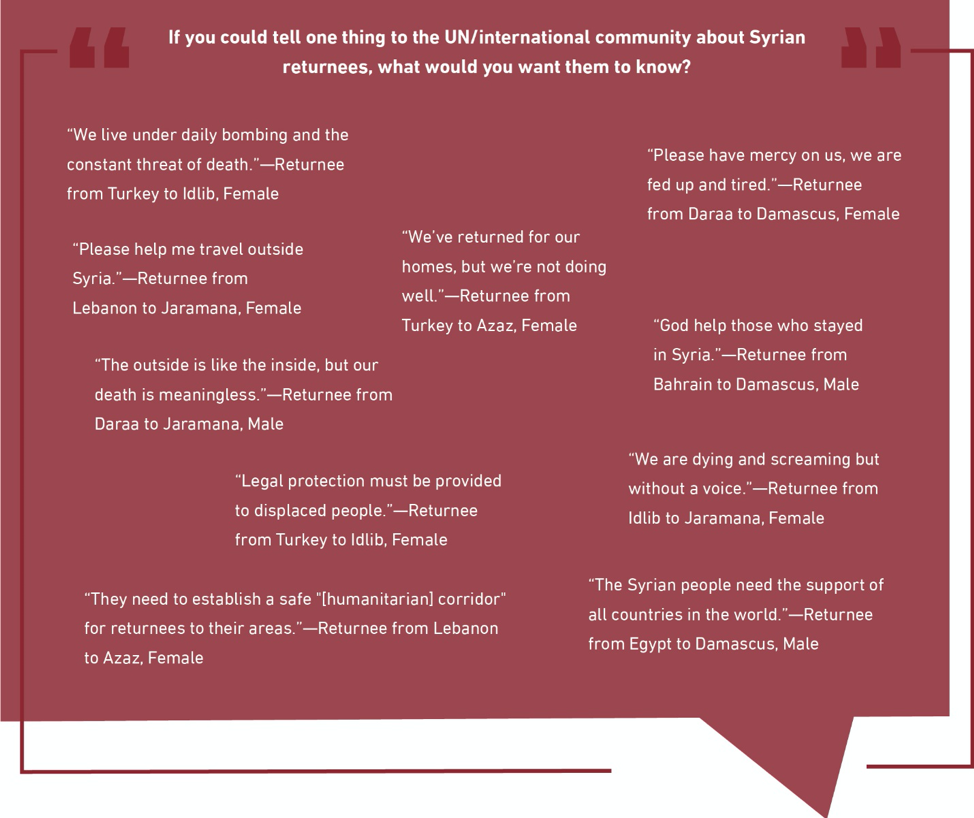

In all policy discussions, Syrian voices — those inside Syria and in the diaspora — must not be neglected. All actors must work to elevate Syrian perspectives and experiences and place them at the center of policy discussions regarding the future of Syria and its people. In this respect, there is an urgent need for joint monitoring mechanisms that pull from nuanced, multi-stakeholder research, and which are capable of safely and accurately monitoring conditions on the ground and Syrians’ experiences with return. Indeed, a lack of genuine engagement means that existing mechanisms are unable to capture safety issues that displaced Syrians face, both within and outside Syria, thereby contributing to forced and coerced returns. This can be solved by greater commitment to collaborating and working with displaced Syrians and Syrian civil society, which will help ensure that their voices and experiences are captured and translated into informed policy.

Finally, voluntary returns are unlikely to happen without a genuine political settlement that includes mechanisms of justice and accountability, both of which remain of paramount importance. Where justice mechanisms are absent inside the country, the U.N., INGOs, and donor countries must not cease in pressuring the GoS and all parties to the conflict to provide adequate and accessible documentation — local or otherwise — to all Syrians, in a way that does not obstruct any individual from accessing humanitarian aid, judicial procedures, law enforcement, health care, education, freedom of movement, legal rights, or their own property.

Ashley Jordan is a humanitarian researcher from the United States. She holds a multidisciplinary Master’s degree in Migration Policy from Erasmus University, and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Mass Communications from Texas State University. She has been visiting fellow at Koç University's migration research center (MiReKoc), and currently works as a research specialist at the Operations and Policy Center in Gaziantep, Turkey.

Samy Akil is a political researcher and analyst originally from the city of Aleppo, Syria. He holds a Bachelor in International Relations (Honors) from La Trobe University and a Masters in Middle Eastern & Central Asian Studies from the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies (CAIS) at The Australian National University. He is the co-founder of the Near East Policy Forum (NEPF) at CAIS and is currently locally engaged at a Canberra-based diplomatic mission. Samy is also an independent consultant at the Operations and Policy Center in Gaziantep, Turkey.

Dr. Karam Shaar is an independent Syria consultant, the Research Director at the Operations and Policy Center, and a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI's Syria Program. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images